10

THE PDB FORMAT, mmCIF FORMATS, AND OTHER DATA FORMATS

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, the data formats and protocols used to represent primary macromolecular structure data are presented. The historical format used by the Protein Data Bank (PDB) is described first. Dictionary-based representations such as the macromolecular Crystallo-graphic Information File (mmCIF) and extensions such as the PDB Exchange dictionary are presented. The translation of the PDB Exchange dictionary into XML or PDB Markup Language (PDBML) is also described. Finally, protocols that provide data access through application program interfaces are described.

THE PDB FORMAT

The Protein Data Bank (http://www.pdb.org/; see also Chapter 11) (Bernstein et al., 1977; Berman et al., 2000) was established in 1971 by Walter Hamilton at Brookhaven National Laboratory, in response to community requests for a central repository of information on biological macromolecular structures. Seven structures were included in the PDB at its inception. The essential elements of the format used to encode these first entries are still the core of the PDB format used today. Because of the simplicity of the format and its consistency in representing three-dimensional structures, the PDB format remains the most widely supported means of exchanging macromolecular structure data.

The PDB format consists of a collection of fixed format records that describe the atomic coordinates, chemical and biochemical features, experimental details of the structure determination, and some structural features such as secondary structure assignments, hydrogen bonding, and biological assemblies and active sites. The details of the format are described in the PDB Contents Guide (Callaway et al., 1996) updated and available at http://www.wwpdb.org. This document enumerates the field formats for each PDB record and remark and describes thePDBconventions for naming atoms, peptides, and nucleotides.

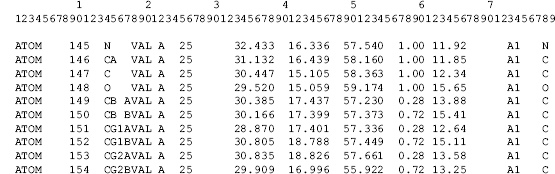

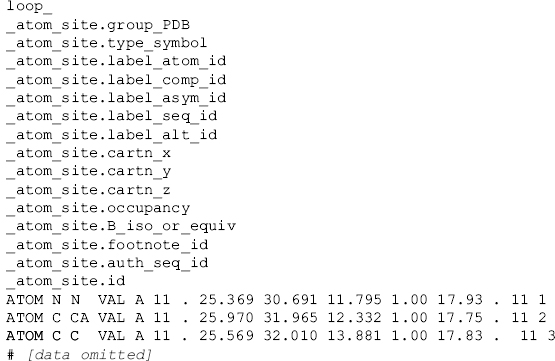

Figure 10.1. An abbreviated example of the column oriented data format for PDB ATOM records. The ATOM records in this example contain fields for the record name, atom serial number, an atom name, a residue name, a polymer chain identifier, a residue number, the x, y, z Cartesian coordinates, the isotropic thermal parameter and the occupancy. Atoms with serial numbers 149–154 also contain a label for alternative conformation in column 17.

Each item of the data in the PDB format is assigned to a range of character positions in one of many PDB record types (HEADER, SOURCE,REMARK, etc.). The ATOMrecords shown in Figure 10.1 encode the atomic coordinate data.ATOMrecords are among the more than 45 named data records in the PDB format. These named data records have strict column formatting rules.

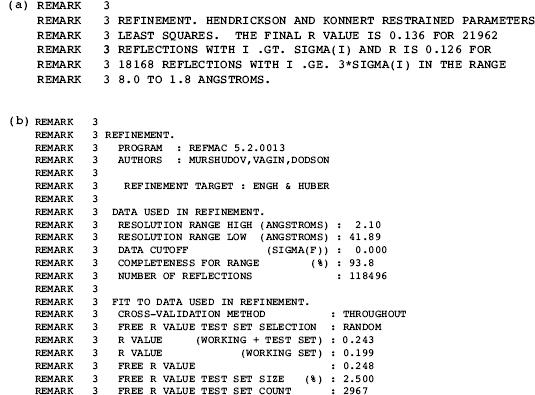

During its early history, the PDB served as a simple repository and a point of dissemination for structure data and was used primarily by crystallographers and NMR spectroscopists. PDB entries during this early period resemble journal publications and contain lengthy descriptive text sections encoded in the REMARK records. An example of how refinement information was coded in pre-1994 PDB entries is shown in Figure 10.2a.

As the number of structures in the archive increased and the user base broadened, the PDBformat required elaboration to enablecomparative analysis of the data in the archive. At a minimum, such comparative studies require a consistent representation of the data and an increase in the types of the data included in each entry. Accordingly, extensions in the PDB format were advanced in 1992 (Protein Data Bank, 1992), 1996 (Callaway et al., 1996), 2006 and 2008 (http://www.wwpdb.org/docs.html). Figure 10.2b is an example of how refinement information is coded in the current PDB format. Prior to 2007, changes in the PDB format were not backwardly propagated to earlier entries. In early 2007, the wwPDB (http://www.wwpdb.org and see Chapter 11) produced a version of the PDB archive in a single consistent PDB format, (Henrick et al., 2008; Lawson et al., 2008). Although the evolution of the PDB format has significantly increased the encoding precision and level of detail for both the biochemical and the experimental descriptions, the format of thePDBcoordinate records has remained largely unchanged.1

While the PDB format has served as the standard for representing macromolecular structure data for over three decades, both the underlying data and the user requirements for this data have changed dramatically. Together these considerations have posed informatics challenges that the current PDB format cannot fully address.

Figure 10.2. (a) Anexample portion of PDBREMARK3 given in the data format used prior to 1992. In this example, information about the refinement is given as free text. (b) An example portion of PDB REMARK 3 given in the current data format. In this example, the text is more structured.

The macromolecular structure data represented in a PDB entry has increased in both type and complexity. In addressing changes in experimental methodology, the PDB format has been extended with new REMARK records. For example, the organization and information content of REMARK 3 that encodes refinement information has been modified and extended for each new refinement program and program version. Although extending REMARK records in this way captures information in a manner that is easy for a human to read, the diversity of organization of these data makes it very difficult to design software that can automatically and reliably extract information from these records. Data in these records are also defined only in terms of the program that computed the information. Information between programs may not be directly comparable.

The PDB format uses fixed width fields to represent data, and this places absolute limits on the size of certain items of data. For instance, the maximums number of atomrecords that can be represented in a single-structuremodel is limited to 99,999, and the field width of the identifier for polymer chains is limited to a single character. Although these restrictions were certainly reasonablewhen the formatwas first defined, this is no longer the case. Many large molecular systems, such as the ribosomal subunit structures, cannot be represented in a singlePDBentry. These entries must be divided into multiple PDB files, seriously complicating their use.

As the size and diversity of structure data in thePDBarchive has grown, it has become an increasingly important resource in structural biology. User requirements for PDB data have grown from accessing individual entries to analysis and comparison of experimental and structure data across the entire archive. The latter has been facilitated by the increased accessibility of database technologies. The support of comparative analysis and database applications requires data uniformity and internal consistency that are typically beyond the needs of the software accessing individual entries, such as molecular graphics applications.

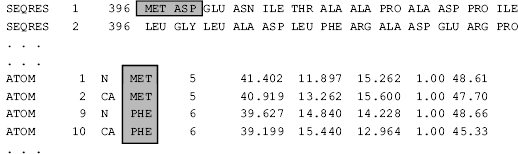

Figure 10.3. An abbreviated example illustrating sequence inconsistency between PDB records. The PDB SEQRES records describe the sequence of the polymer that was crystallized. The sequence labels in the PDB ATOM records report the coordinates and the residue sequence observed in the refined structure. These should be consistent; as shown in this example, there have often been exceptions. This example highlights the sequence conflict between ASP in the chemical sequence (SEQRES) with PHE, residue number 6 in the ATOM records.

The difficulty of reliably extracting experimental information from each entry has already been discussed in terms of the format variation of REMARK records used to encode experimental details (e.g., refinement information in REMARK 3). Internal consistency problems within PDB entries arise in cases in which portions of the structure or individual structural elements are referenced in different PDB records in a noncorresponding manner. Because the PDB format does not specify the precise relationship between the polymer sequence given in the SEQRES records and the observed residue sequence within the ATOM records, the sequence information that is presented in the PDB entry cannot be used directly. To use these data, additional sequence alignment must be performed to resolve gaps and possible conflicts. An example of this is shown in Figure 10.3.

Consistency problems can also arise in other records that reference structural features such as those records describing secondary structure, active sites, and biological assemblies. Although the relationships between these records and the coordinate data that they reference are obvious to the experienced user, they can only be understood by a careful reading of the format description document. Because these relationships are not electronically accessible, each such relationship must be coded as a special case by any software that needs to validate interrecord consistency.

mmCIF: A DICTIONARY-BASED APPROACH TO DATA DESCRIPTION

The Crystallographic Information File (Hall, Allen, and Brown, 1991) was created to archive information about crystallographic experiments and results (Hall, 1991) and is the format in which allstructures described in articles sentto Acta CrystallographiaC are submitted. In 1990, the International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) formed a working group (Fitzgerald et al., 1992) to expand this dictionary so that it would be able to do the same for macromolecules.

The original short-term goal of the working group was to fulfill the mandate set by the IUCr: to define mmCIF data names that needed to be included in the CIF dictionary in order to adequately describe the macromolecular crystallographic experiment and its results. This implied the need to describe all of the data items included in a PDB entry. Long-term goals were also established: to provide sufficient data names so that the experimental section of a structure paper could be written automatically and to facilitate the development of tools so that computer programs could easily access and validate the mmCIF data files.

In order to describe the progress of this project and to solicit community feedback, several informal and formal meetings were held. The first meeting, hosted by Eleanor Dodson, convened in April 1993 at the University of York. The attendees included the mmCIF working group, structural biologists, and computer scientists. A major focus of the discussion was whether the formal structure of the dictionary that was implemented using the then-current Dictionary Definition Language (DDL 1.0) (Westbrook et al., 2005a) was adequate to deal with the complexity of the macromolecular data items. Criticisms included the idea that the data typing was not strong enough and that there were no formal links among the data items. Aworking group was formed to address these issues. The second workshop was hosted by Phil Bourne in Tarrytown, NY, in October 1993. The meeting focused on the development of software tools and the requirements of an enhanced DDL. In October 1994, a workshop hosted by Shoshana Wodak at the Free University of Brussels resulted in the adoption of a new DDL that addressed the various problems that had been identified at the preceding workshops. The evolving mmCIF dictionary was cast in this new DDL 2 (Westbrook et al., 2005a) and was presented at the ACA meeting in Montreal in July 1995. This dictionary was open for further community review. The dictionary was placed on a world wide web site and community comments were solicited via a list server. Lively discussions via this mmCIF list server ensued, resulting in the continuous correction and updating ofthe dictionary. Software was developed and was also presented on this www site. A workshop held at Rutgers University in 1997 provided tutorials for using both the dictionary and the software tools that had been developed at that time.

In January 1997, an mmCIF dictionary containing 1700 definitions was completed and submitted to the IUCr committee that oversees dictionary development (COMCIFS) for review, and in June 1997, Version 1.0 was released (Fitzgerald et al., 1996; Bourne et al., 1997). The method adopted for managing dictionary extensions involves the use of a scientific journal as a model. Proposed extensions are sent to the editors of the mmCIF dictionary (Fitzgerald et al., 1996; Editorial Board: Paula Fitzgerald, editor; Helen Berman, associate editor) who send the new definitions to a member of the board of editors for scientific review. These editors have expertise in various areas covered by the dictionary. Once the definitions are reviewed for their scientific content, they are sent to technical editors. More than 100 new definitions were proposed after the dictionary was released in 1997 and these have been reviewed using the procedures outlined. Version 2 of the mmCIF dictionary was released in the fall of 2000 and this new version contains many of these new definitions.

Software libraries to parse and access data in CIF and mmCIF have been produced for a number of popular languages including C/C++, JAVA, FORTRAN, PERL, and Python (http://sw-tools.pdb.org or http://www.iucr.org for lists of programs).

mmCIF Dictionary and Data File Syntax

The syntax used in both mmCIF data files and dictionaries derived from the STAR (Self-defining Text Archive and Retrieval) (Hall, 1991) grammar and is similar in most respects to the syntax used by core CIF for describing small molecule crystallography.

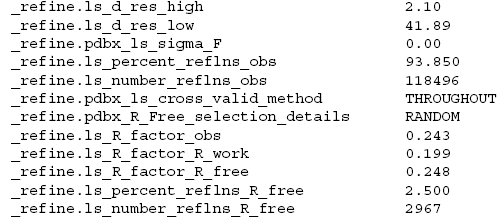

Figure 10.4. An example portion ofthe mmCIF REFINE category containing the same information as in the PDB REMARKs in Figure 10.2a-b. This example illustrates keyword-value pair formatting that is characteristic of the mmCIF syntax.

In its simplest form, an mmCIF data file looks like a paired collection of data item names and values. Figure 10.4 illustrates the assignments of values to selected refinement parameters analogous to the PDB format data in Figure 10.2b. The syntax is described here.

The leading underscore character identifies data item names. The underscore character is followed by a text string interpreted as containing both a category name and an item name separated by a period. The keyword portion of the name is the unique identifier of the data item within the category. In the examples shown in Figure 10.4, all of the data items belong to the REFINE category. This example also illustrates the one-to-one correspondence required between item names and item values. Data category and data item names are not case sensitive.

Figure 10.5 illustrates how text strings are expressed. Short text strings may be enclosed in single or double quotation marks. Text strings that span multiple lines are enclosed by semicolons that are placed at the first character position of the line. There are two special characters used as placeholders for item values that for some reason cannot be explicitly assigned. The question mark (?) is used to mark an item value as missing. A period (.) may be used to identify that there is no appropriate value for the item or that a value has been intentionally omitted.

Figure 10.5. An example illustrating the encoding of text strings using mmCIF. Short strings, such as Data set 1 and omega scan, are surrounded by either single or double quotation marks. Multiline strings such as the value of _diffrn_measurement. details are encapsulated by semicolons in the first column of the beginning and ending lines of the string.

Figure 10.6. An abbreviated example of the mmCIF category ATOM_SITE. This category is organized as a table and illustrates the use of the loop_ directive followed by the list of data item names as the simple means of declaring an mmCIF table. The data values that follow the list of data item names are assigned to each data item (column) in turn. Here, the value, ATOM, is assigned to the column for _atom_site.group_PDB in each of the three rows in this example.

Vectors and tables of data may be encoded using a loop_ directive. To build a table, the data item names corresponding to the table columns are preceded by the loop_ directive and followed by the corresponding rows of data. The mmCIF example in Figure 10.6 builds a table of atomic coordinates.

The use of the loop_ directive has a few restrictions. First, it is required that all of the data items within the loop belong to the same data category. Second, the number of data values following the loop must be an exact multiple of the number of data item names. Finally, mmCIF does not support the nesting of loop_ directives.

Data blocks are used to organize related information and data. A data block is a logical partition of a data file or dictionary created using a data_ directive. A data block may be named by appending a text string after the data_ directive, and a data block is terminated by either another data_ directive or by the end of the file. Figure 10.7 shows a very simple example of a pair of abbreviated data blocks.

Figure 10.7 illustrates how data blocks can be used to separate similar information pertaining to different structures. This separation is required because the mmCIF syntax prohibits the repetition of the same category at multiple places within the same datablock. As a result, the simple concatenation of the contents of the above two data blocks into a single data block would be syntactically incorrect.

Figure 10.7. An abbreviated example illustrating the organization of mmCIF files in data blocks. Data blocks are declared using the data_ directive and optionally followed by a data block name. In this example, data blocks X987A and T100A are declared. The information in these data blocks is treated as logically distinct even if the data block exists within the same data file.

Definitions in mmCIF data dictionaries are encapsulated in named save frames (Figure 10.8). A save frame is a syntactical element that begins with the save_ directive and is terminated by another save_ directive. Save frames are named by appending a text string to the save_ directive. In the mmCIF dictionary, save frames are used to encapsulate item and category definitions. The mmCIF dictionary is composed of a data block containing thousands of save frames, where each save frame contains a different definition. Save frames appear in data dictionaries but they are not used in data files. Save frames may not be nested.

The content of this dictionary definition has the same item-value pair organization as in the previous data file examples. DDL2 dictionary definitions typically contain a small number of items that specify the essential features of the item. The example definition shown in Figure 10.8 includes a description or text definition, the name and the category of the item, a code indicating that the item is optional (not mandatory), the name of a related definition in the core CIF dictionary, and a code specifying that the data type is text. A further description of the elements of the dictionary definitions is presented in the next section.

Figure 10.8. An example ofthe mmCIF data definition for data item _exptl.details. This definition contains a textual definition, name and category identity, a code indicating the item is optional, an alias name to a previous dictionary, and a data type.

Semantic Elements of the mmCIF Data Dictionary

The elements of DDL provide the organizational framework for building data dictionaries such as mmCIF. The role of the DDL is to define which data items may be used to construct the definitions in the data dictionary and to define also the relationships between these defining data items.

The dictionary language contains no information about a particular discipline such as macromolecular crystallography; rather, it defines the data items that can be used to describe a discipline. The contents of the mmCIF dictionary are metadata, or data about data. The contents of the DDL are meta-metadata, the data defining the metadata. DDL defines data items that describe the general features of a data item, such as a textual description, a data type, a set of examples, a range of permissible values, or perhaps a discrete set of permitted values. Consequently, data modeling using DDL can be applied in many application areas, not just macromolecular structure description.

The lowest level of organization provided by the DDL is the description of an individual data item. Collections of related data items are organized in categories. Categories are essentially tables in which each repetition of the group of related items adds a row. The terms category and data item are used here in order to conform with the previous use of these terms by STAR and CIF applications; these terms could be replaced by relation and attribute (or table and column), terms which are commonly used to describe the relational model that underlies the DDL.

Within a category, the set of data items determining the uniqueness of their group are designated as key items in the category. No data item group in a category is allowed to have a set of duplicate values of its key items. Each data item is assigned membership in one or more categories. Parent-child relationships may be specified for items belonging to multiple categories. These relationships permit the specification of the very complicated hierarchical data structures required to describe macromolecular structure.

Other levels of organization in addition to category are also supported. Related categories may be collected together in category groups, and parent relationships may be specified for these groups. This higher level of association provides a method for organizing a large and complicated collection of categories into smaller, more relevant, and potentially interrelated groups. This effectively provides a chaptering mechanism for large and complicated dictionaries, such as mmCIF. Within the level of a category, subcategories of data items may be defined among groups of related data items. The subcategory provides a mechanism to identify, for example, that the data items month, day, and year collectively define a date.

For categories, subcategories, and items, methods may be specified. Methods are computational procedures that are defined and expressed in a programming language (e.g., C/C++, PERL, Python, or JAVA) and stored within a dictionary. Among other things, these dictionary methods may be used to calculate a missing value or to check the validity of a particular value.

The highest levels of data organization provided by DDL2 are the data block and the dictionary. The dictionary level collects a set of related definitions into a single unit, and provides the attributes for a detailed revision history on the collection.

The detailed features of the DDL used to build the mmCIF data dictionary are described elsewhere (Westbrook and Bourne, 2000; Westbrook et al., 2005a and b).

mmCIF Dictionary Content

Version 1.0 of the mmCIF dictionary contains approximately 1,700 definitions describing the macromolecular experiment and its structural results. This dictionary includes definitions describing all aspects of macromolecular structure; experimental details about crystallization, data collection, data processing, phasing, and refinement; and other supporting data categories describing citation and software. A complete discussion of the contents of the mmCIF dictionary has been previously provided (Bourne et al., 1997; Fitzgerald et al., 2005).

The following section provides a summary of a portion of mmCIF data categories describing chemical structure. In this discussion, the data categories are presented in the form of a schematic diagram, a brief description, and a set of examples. In the diagrams, boxes enclose the data items within each mmCIF category, and arrows indicate the correspondence between data items that are common to multiple categories, with the arrow heads pointing in the direction of the parent data item. The category key data items are indicated with black dots.

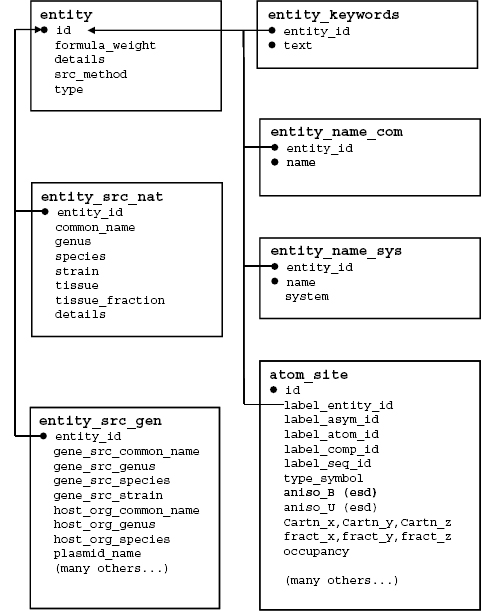

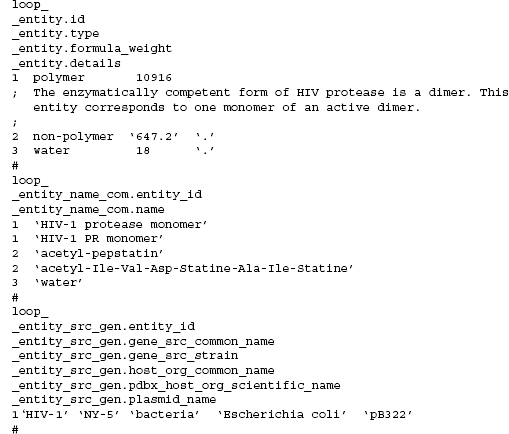

mmCIF Molecular Entities. An entity is a chemically distinct part of an mmCIF entry. There are three types of entities: polymer, nonpolymer, and water. A common name, systematic name, source information, and keyword description can be assigned to each mmCIF entity. The relationships between categories that describe these entity features are illustrated in Figures 10.9 and 10.10 is an example of an entity description taken from an HIV protease structure (PDB 5HVP; Fitzgerald et al., 1990).

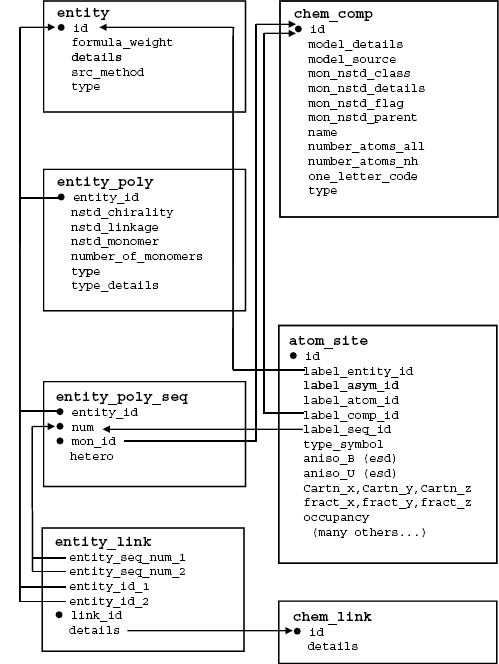

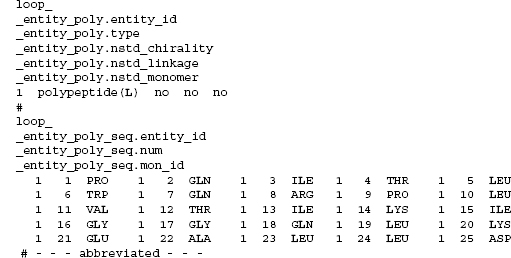

mmCIF Polymer and Nonpolymer Entities. Additional data categories are provided to describe polymeric entities. Polymer type, sequence length, and information about nonstandard linkages and chirality may be specified. The monomer sequence for each polymer entity is listed in category ENTITY_POLY_SEQ. This sequence information is directly linked to the sequence specified in the coordinate list. It is also linked to the full chemical description of each monomer or nonstandard monomer in the CHEM_COMP category group. The relationships between categories describing polymer entities are illustrated in Figure 10.11 and Figure 10.12 shows an example of the description of a polymeric entity for a simple protein.

Figure 10.9. A schematic diagram illustrating the content and relationships among a portion of the mmCIF categories describing chemical entities, entity names, entity source organism, and the relationship between the entity and atomic level of description. In this figure, boxes enclose the data items within each mmCIF category, and arrows indicate the correspondence between data items that are common to multiple categories, with the arrow heads pointing in the direction ofthe parent data item. The category key data items are indicated with black dots.

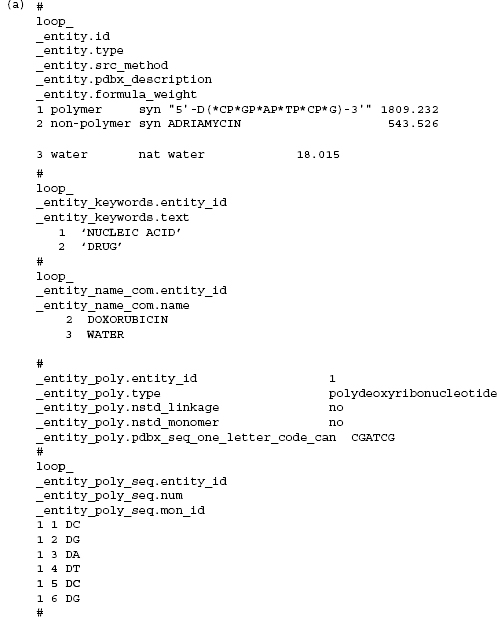

Nonpolymeric entities are treated as individual chemical components. These entities may be fully described in the CHEM_COMP group of categories in the same manner as monomers within a polymeric entity. Like polymeric entities, each nonpolymeric entity carries both an entity identifier and a component identifier. These identifiers form part of the label used to identify each atom(_atom_site.label_entity_id and_atom_-site.label_comp_id). For polymeric entities, the monomer identifier and the component identifier are the same; however, the atom label also includes an additional field for the sequence position (_atom_site.label_seq_id). An example for a drug-D-NA complex illustrating both polymer and nonpolymer entity descriptions is shown in Figure 10.13a.

Figure 10.10. An abbreviated example ofthe mmCIF description ofthe chemical features of HIV protease. In this example, three entities are defined. One entity is a monomer of HIV protease, the second is the peptidic inhibitor, and the third is solvent. Common names for these entities are specified. The source organism from which the protein sequence was obtained is also specified in this example.

Atomic Positions. The refined coordinates are stored in the ATOM_SITE category. Atomic positions and their associated uncertainties may be stored in either Cartesian or fractional coordinates along with the option to store temperature factors and occupancies for each position.

Each atomic position must be uniquely identified by the data item _atom_site.id. Each position must also include a reference (_atom_site.type_symbol) to the table of elemental symbols in category ATOM_TYPE. All other data items in ATOM_SITE category are optional.

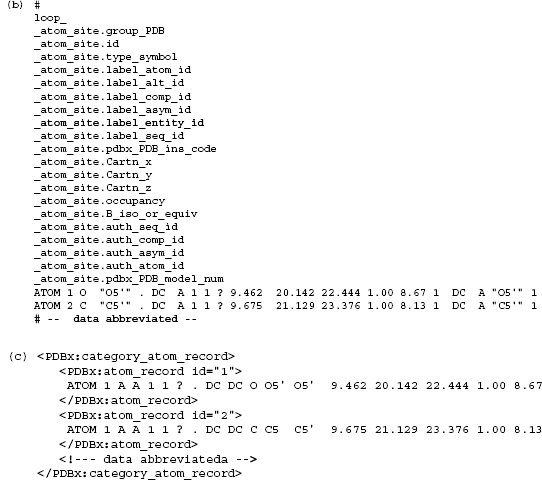

A typical atomic position for a macromolecule includes a variety of label information, as illustrated in Figure 10.13b. The data items that label atomic positions can be divided into two groups: those that are integrated into higher level structural descriptions and those that are provided to hold alternative nomenclatures. The data items in the former group are prefixed by label_ and the latter carry an auth_ prefix.

Figure 10.11. A schematic diagram illustrating the content and relationships among the mmCIF categories describing polymer entities. In this figure, boxes enclose the data items within each mmCIF category, and arrows indicate the correspondence between data items thatare common to multiple categories, with the arrowheads pointing in the direction of the parent data item. The category key data items are indicated with black dots.

THE PDB EXCHANGE AND OTHER DATA DICTIONARIES

The wwPDB (Berman etal., 2003 and see Chapter11) uses technology based on mmCIF for content description, data exchange, and data archiving. The PDB Exchange dictionary (Westbrook et al., 2005a) incorporates the content of the mmCIF dictionary, as well as extensions for high-throughput Structural Genomics (ISGO, 2001); noncrystallographic methods such as NMR and cryoelectron microscopy; protein production; and internal data management and status tracking. Within this dictionary framework the wwPDB provides a consistent representation of experiment and structure of macromolecular systems spanning a scale from small oligomers to subcellular assemblies and molecular machines.

Figure 10.12. An abbreviated mmCIF description of polymer entity, including the enumeration of the three-letter residue codes of the entity polymer sequence.

In addition to the PDB Exchange dictionary, the mmCIF methodology has been used to describe a number of other content areas. All of these dictionaries have been developed to be consistent with the mmCIF data model. These dictionaries, which are all available from the mmCIF resource site (http://mmcif.pdb.org), cover the following content areas:

- The imgCIF dictionary (Hammersley et al., 2005) provides details of crystallograph-ic data collection including data from image detectors in ASCII and binary data format.

- The BIOSYNC (http://biosync.pdb.org) dictionary describes the features and facilities provided by synchrotron beamlines.

- The MDB dictionary is an extension of the mmCIF dictionary for homology models.

- The Symmetry extension (Brown, 2005) supplements the mmCIF dictionary with detailed aspects of crystallographic symmetry.

- The NMRSTAR dictionary supplements the structural description of NMR in the PDB Exchange dictionary with the experimental details collected and archived by the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB; Seavey et al., 1991).

SUPPORTING OTHER FORMATS

Much attention in the area of data format has recently been focused on technologies related to the extensible markup language (XML). XML provides a framework for structuring complex information and documents. XML is used as a data exchange vehicle in a variety of software platforms. A growing number of commercial and public domain software applications provide support for XML. Many of these applications provide sophisticated display and query features that can be applied to the XML data. Owing to the availability of off-the-shelf access and query tools, this format would appear to be a good choice for storing structure data.

Figure 10.13. An abbreviated example of an mmCIF description of a drug-DNA complex. This example includes the description of both the DNA strand and the drug adriamycin. The mmCIF categories depicted in Figures 10.9 and 10.10 are populated in this example. In particular, this example illustrates how mmCIF describes the chemistry of both polymer and nonpolymer molecules. (a) The chemical entities in this drug complex are defined. The first entity is the DNA polymer strand and the second entity is the drug adriamycin. The nucleotide sequence of the DNA is enumerated.(b)The list of chemical components in the complex is specified. This includes the nucleotide monomers, the drug, and the solvent. The atomic coordinates of a portion of the first nucleotide (cytosine) are given. This coordinate data is explicitly related to the chemical description through identifiers for entity (_atom_site.label_entity_id = 1), component (_atom_site.label_comp_id = DC), and sequence order (_atom_site.label_ seq_id =1).

The representation of PDB structure data in XML is based on the mapping of content from the PDB Exchange dictionary to an XML schema. XML schemas (http://www.w3c.org/XML/Schema) provide a means of defining the structure, content, and semantics of XML documents analogous to the role the mmCIF dictionaries play for mmCIF data files. Like mmCIF dictionaries, XML schemas provide support for strong data typing, complex data types, enumerations, range restrictions, and parent-child and key relationships.

In creating the PDBML schema, the naming conventions and logical organization used within PDB exchange dictionary have been preserved. The content mapping between data dictionary and schema is fully software driven (Westbrook et al., 2005c). A consequence of maintaining the logical organization of the mmCIF dictionary mapping is that PDBML data files lack the embedded hierarchical organization characteristic to many XML files. Instead, the hierarchical structure in PDBML files is represented in XML key-keyref relationships just as with the mmCIF parent-child relationships. An important advantage of representing data in regular table-like containers is that a custom parser is not required to navigate a complex hierarchy of data elements, and that extensions to the data model require little if any supporting software changes.

An example is given in Figures 10.14a-b; the former is a PDBML encoding of the data shown in an mmCIF representation in the latter. This example illustrates the essential mapping between mmCIF and PDBML. Each mmCIF category is encapsulated with an XML element that pairs the category name with the appended token Category. Each row of the mmCIF category is enclosed in an element named after the category and including any key mmCIF data items as XML attributes. Nonkey mmCIF data items are represented as XML elements. All data XML element names are prefixed with the XML namespace, PDBx. This example also illustrates the large overhead of XML tags. For a medium-sized protein structure of 200 residues, this results in a 10-fold increase in data file size. Figure 10.14c shows an alternative style in which the atom coordinate records are stored as a string without detailed markup. In the latter example, the string of atomic coordinate information is matched against a regular expression in the PDBML schema defining the record organization. While the latter approach gains storage efficiency, this efficiency is achieved with a loss of the detailed access and search functionality of the fully marked-up form.

SUPPORTING APPLICATION PROGRAM INTERFACES

No single file format is satisfactory for all users and applications. One way to avoid file format issues entirely is to provide access to data through an application program interface (API). Depending on the languageimplementation the API provides access to data througha collection of functions, procedures, or methods. While a wide range of API technologies are available, two approaches have been commonly applied for exchanging macromolecular structure data.

The Object Management Group (OMG) standardizes the developed API by using its Common Object Request Broker Architecture (CORBA). CORBA supports an interface definition language (IDL) for defining programmable interfaces that are both language and platform independent. CORBA has also been developed to support distributed cross-platform access. The CORBA IDL for macromolecular structure (http://cgi.omg.org/cgibin/http://www://cgi.omg.org/cgi-bin/doc?lifesci/00-02-02) is based on the mmCIF data representation and provides efficient program access to all of the data in PDB entries.

Access to data and query functionality for a wide range of biological resources is provided by web services based on the Web Services Description Language (WSDL; http://www.w3.org/TR/wsdl) and the Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP) (http://www.w3.org/TR/2000/NOTE-SOAP-20000508/). This approach leverages XML data encoding and widely used network transport protocols such as HTTP to provide distributed cross-platform access to data and query services. WSDL provides XML-encoded definitions of data and query services along with the content of messages exchanged between servers and their clients. SOAP provides the protocol by which messages are transmitted over the network. At the time of this writing, web services were deployed for testing at each of the wwPDB distribution sites.

Figure 10.14. (a) An abbreviated example of PDBML encoding of data from the atom_site category. In this example, the coordinates of two atoms are included. Each coordinate record is enclosed within <PDBx:atom_site> tags. The other item names are taken directly from the item names defined in the mmCIF dictionary less the category name. For instance, the value of _atom_site.id the unique identifier or category key for this category is presented as an XML attribute (i.e., <id=“1”>). Other data items are encoded as XML data elements (e.g., <PDBx: type_symbol></PDBx :type_symbol>). All ofthe PDBML element names are qualified with the XML namespace, PDBx. (b) The data corresponding to Figure 10.14a expressed using mmCIF. In the mmCIF representation, the keywords defining the data items are specified once as part of the loop_ declaration. (c) The PDBML presentation for the data in Figure 10.14a using the more efficient alternative atom record markup.

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, the syntactical features of a number of ways to represent macromolecular structure data have been discussed. Each of these has its strengths and weaknesses. The PDB format is simple and accessible with very simple software tools. PDBML provides great flexibility and is well supported by commercial and public domain software. Far more important than the details of syntax is the ability of a particular data representation to precisely define data in a manner that is completely electronically accessible. The particular strength of the mmCIF approach is that it is based on a data dictionary. This data dictionary provides the detailed semantics, including precise definitions, and examples combined with a robust metadata model, which can be exploited by software to perform detailed checks on individual data items as well as checks of the internal consistency between data items. The dictionary also provides the necessary semantic information to support lossless translation into alternative data formats and application program interfaces.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The development of the mmCIF dictionary and the associated DDL was an enormous community task, and the authors realize that any list of contributors to the effort will certainly be incomplete. Much of the mmCIF dictionary development was done by the original working group, including Enrique Abola, Helen Berman, Phil Bourne, Eleanor Dodson, Art Olson, Wolfgang Steigemann, Lynn Ten Eyck, and Keith Watenpaugh. Evaluation and critique of the dictionary development process was greatly aided by the input from COMCIFS, the IUCr committee with oversight over this process (I. David Brown and Brian McMahon). Many members of the community provided valuable input during the public review of the mmCIF dictionary. Frances Bernstein, Herbert Bernstein, Dale Tronrud, Kim Henrick, and Peter Keller were particularly active in this review process. Sydney Hall, Michael Scharf, Peter Grey, Peter Murray-Rust, Dave Stampf, and Jan Zelinka contributed to defining the requirements for the mmCIF DDL. The development of the PDB Exchange dictionary has been a collaborative effort within the wwPDB with significant contributions from Helen Berman, Kim Henrick, John Markley, Eldon Ulrich and Cathy Lawson. PDBML was also developed as a wwPDB collaboration with significant participation from Nobutoshi Ito, Haruki Nakamura, Helen Berman, and Kim Henrick.