18

THE CATH DOMAIN STRUCTURE DATABASE

INTRODUCTION

Protein sequences change during evolution due to both mutations in their residues and the insertion and deletion of residues. These changes give rise to families of related proteins. The earliest protein family resources were first established in the 1970s by the pioneering work of Dayhoff and many other sequence databases have been established since then. These resources are derived solely from sequence data and relationships are often detected using alignment methods based on powerful dynamic programming algorithms adapted from the realm of computer science. Such methods very efficiently handle residue insertions and deletions occurring between distant evolutionary relatives.

Structural data have always been sparser than the sequence data due to the technical challenges of structure determination. There is currently over two orders of magnitude discrepancy between the sequence and structure resources. Thus, while the Protein Data Bank (PDB) contains about 42,500 structural entries, the sequence databank at the NCBI (GenBank) contains over 60 million entries.

Although the first crystal structures were solved in the early 1970s, it was not until the mid-1990s that structural classifications began to emerge, primarily with SCOP (Murzin et al., 1995; Andreeva et al., 2004), DALI (Holm and Sander, 1996), and CATH (Orengo et al., 1997; Greene et al., 2007) databases and data resources. Since then, several other structure classifications and nearest-neighbor resources have arisen, including 3Dee (Dengler, Siddani and Barton, 2001), DaliDD(Holm and Sander, 1998; Dietmann and Holm, 2001) and VAST (Madej et al., 1995). These resources use a variety of different algorithms for comparing 3D structures (see Chapter 16). They also differ in methods for measuring similarity between the structures and clustering them into fold groups or protein superfamilies and families. However, comparisons between three of the largest classifications SCOP, DALI, and CATH (Hadley and Jones, 1999; Day et al., 2003) reveal a reasonable degree of correspon-dence between protein families generated using different protocols.

Since structure is much more highly conserved than sequence during evolution, the discovery of structural alignment algorithms and the development of structural classifications have made a significant contribution to understanding evolutionary mechanisms as they have enabled much more distant evolutionary relatives to be identified. Furthermore, knowledge of a protein structure can provide important clues to the functional mechanism and biological role of the protein, for example, protein-substrate and protein-protein interactions (see Chapters 25 and 26). Because a large proportion of the structural core of the protein (often more than 50%) is conserved even in very distant relatives, structure alignments are much more accurate than sequence alignments and this improves the identification of conserved structural features or sequence motifs that are often associated with protein function.

The largest structure classifications (SCOP, CATH) currently contain 1500-2100 protein superfamilies. These superfamilies, however, only map to approximately half of the nonredundant sequences in the GenBank sequence database (~46% on the basis of equivalent residues). The ongoing structure genomics initiatives, described in Chapter 40, will significantly increase the number of novel structures determined over the next 10 years to increase this coverage. Current estimates predict that there could be up to 100,000 new structures before the end of the decade. Because of the manner in which proteins are being selected for structure determination, these new structures will predominantly be from currently underrepresented or distantly related to known protein families in the structure classifications. Therefore, we may soon have structural representatives for most of the major protein families and those of particular medical and biological interest, although some classes of structures such as transmembrane proteins may remain difficult to determine. It is also likely that methods for detecting distant relatives will improve in parallel as a consequence of the growth in the sequence and structure databases. Links between the sequence and structure databases are increasing. The InterPro initiative has integrated several sequence databases (Pfam, PRINTS, PROSITE, SWISS-PROT). This has been extended so that structural assignments from SCOP and CATH and the European Macro-molecular Structure Database (EMSD) are now included.

Structural classifications will therefore play an increasingly important role as representatives from more protein families are structurally determined and the mapping between structural families and genomic sequences improves. These resources will provide key data for understanding function at the molecular level. In this chapter we describe the CATH structural classification, its development, and the methods used to update and search the resource. Analysis of the classification has revealed that some protein families are very highly populated, a finding that has important implications for understanding evolutionary mechanisms, and is discussed later in the chapter. Information regarding the mapping of structural domains in CATH superfamilies onto genome sequences and a summary of some insights into protein evolution that can be gleaned from analyzing these data are presented in Chapters 22 and 23.

The CATH domain structure database was established in 1993 when less than 3000 protein structures had been determined. Nearly a decade later, the database has expanded considerably and contains ~30,000 protein structure entries from the PDB comprising over 93,000 structural domains. CATH’s related resource Gene3D, contains approximately 1 million domains extracted from GenBank and UniProt entries that are assigned to one of the 2091 CATH homologous superfamilies using profile-based approaches. Since the domain is considered to be an important evolutionary unit and also because structural prediction and homology modeling methods are often more successful on a domain basis, CATH was established as a domain-based database.

Most publicly available structure classifications are derived using sequence- and/or structure-based protocols. These range from the completely automated approaches of DALI and the DALI Domain Database to the largely manual approach used in compiling the SCOP database. In the CATH database, semiautomated protocols are used for clustering structures both phonetically on the basis of structural similarity and phylogenetically on the basis of apparent evolutionary relatedness. Any ambiguities in the assignments from automated protocols are validated manually and major bottlenecks in the classification correspond to the detection of domain boundaries and the verification of homologous relationships.

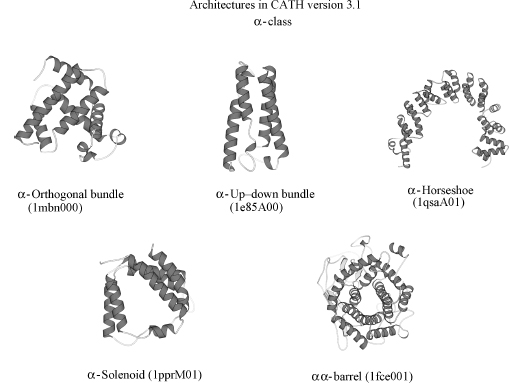

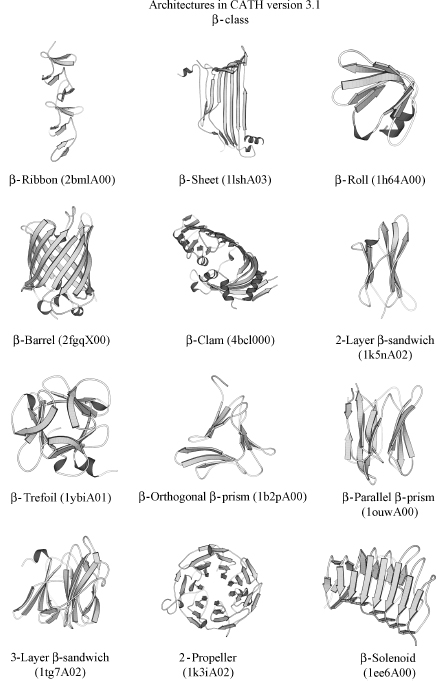

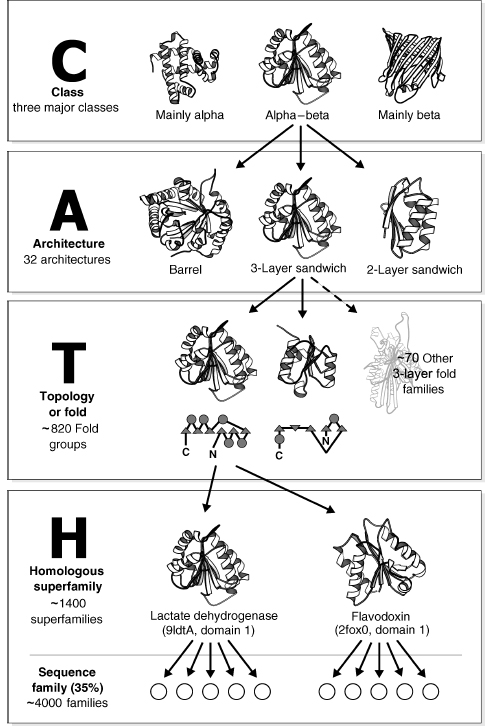

CATH is a hierarchical classification comprising four major levels (see Figure 18.1). In fact, CATH is an acronym for these levels: Class, Architecture, Topology, and Homology. At the top, the protein (C)lass is determined by the secondary structure composition and packing using an automated approach. (A)rchitecture describes the orientation of the secondary structures in 3D space, regardless of their connectivity. For example, a large number of protein structures adopt alpha-beta barrel architectures, in which a central barrel of beta strands is enclosed within an outer barrel comprising a layer of alpha helices (see Figure 18.2). At the next level in the hierarchy, (T)opology, both secondary structure orientation and connectivity between the secondary structures are taken into account in describing the fold of the protein. For the example shown in Figure 18.1, the three-layer alpha-beta sandwich architecture contains more than 100 different folds or topologies in which the secondary structures adopt a similar shape in 3D but the connectivities between them can differ considerably as shown by the schematic representations in the illustration. At the fourth and perhaps most biologically important level in the classification, (H)omologous superfamily, proteins are grouped according to whether there is sufficient evidence (structural, sequence, and/or functional similarity) to support an evolutionary relationship. Within each homologous superfamily, proteins are clustered into sequence families at different levels of sequence identity (35,60,95, and 100%). More recently, protocols have been developed for identifying functional families within each superfamily.

There are currently three major classes within CATH, corresponding to mainly alpha, mainly beta, and alpha-beta domains. Other categories distinguished at the class level are multidomain proteins; domains comprising few secondary structures and three groups corresponding to proteins at different stages in the classification and pending assignment to a particular fold group or superfamily. In release 3.01, January 2007, CATH contained 40 architectures; 1084 fold groups, and 2091 homologous superfamilies. Further statistics on the database and discussion of the population of different levels are given in the following section.

CURRENT METHODOLOGIES FOR IDENTIFYING STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES AND EVOLUTIONARY RELATIONSHIPS IN CATH

Phylogenetic and phonetic relationships in the CATH database were initially identified using the powerful structure comparison algorithm, SSAP, devised by Taylor and Orengo (1989) in 1989, which incorporated a modified dynamic programming algorithm performing at two levels and thus enabling comparison of 3D information. More recently, fast graph-based methods for structure comparisons have been implemented to enable the database to keep pace with the structure genomics initiatives. In fact, sequence-based methods are first used to detect close relatives, as these are much faster than structure comparison and pair-wise methods are reliable for relatives with 35% or more sequence identity. Sensitive profile-based sequence methods are used to detect more distant homologues that can then be verified by structural similarity.

Figure 18.1. Schematic representation of the class, architecture, topology/fold, and homologous superfamily levels in the CATH database.

The strategy used in classifying new structures into the database can thus be broken down into the following major steps: (1) Close relatives are identified first using pair-wise sequence methods. Structure comparison is used to extract accurate domain boundaries. (2) Domain boundaries for all other entries are determined by running sequence profiles, structure comparison protocols, and ab intio domain boundary prediction algorithms. Domain boundaries are then manually validated. (3) Sequence profiles and structural comparison methods are used to identify distant evolutionary relatives or fold matches, and structures are assigned to a superfamily or fold group. (4) Finally, any new unclassified structures are manually assigned to architectures within CATH or assigned new architectures (see Figure 18.3). Only Stage 1 is fully automated, the other stages include algorithms and manual validation protocols used at different stages of the classification. These methods are described in the following section.

CLASSIFYING CLOSE HOMOLOGUES (CHOPCLOSE)

To maintain the integrity of CATH domain boundaries within the classification, only very close homologues are completely classified automatically. Several studies have shown that when two proteins share more than 30% identity in their sequences, they have similar structures and can be assigned to the same superfamily. Furthermore, pair-wise sequence alignment methods are reasonably robust at these levels of sequence identity. In CATH, the global alignment method of Needleman and Wunsch (1970) has been implemented. With the demonstration by Rost and Sander showing homologue identification to be dependent on sequence length, with unrelated small proteins of less than 100 residues sometimes exhibiting sequence identities as high as 30%, a more cautious threshold of 80% identity is used for homologue detection.

Having identified a close homologue, the SSAP residue-based structural comparison algorithm (Orengo and Taylor, 1996) is run against the data to obtain the optimal alignment between the structures. Benchmarking has shown that SSAP is more effective than both pair-wise sequence alignment and sequence profiles at delineating domain boundaries.

To maintain further consistency within the domain family, we checked that at least 80% of the larger protein is aligned against the smaller protein, and that no more than a10 residue extension is observed at either end of the alignment. Relatives identified by these pair-wise methods are clustered into their respective families using a multilinkage clustering algorithm.

Figure 18.3. A schematic showing the CATH update protocol. The first major step is DomChop, where one or more domains are assigned for each chain. In many cases, these boundaries can be automatically assigned; those that cannot are manually curated. The newly created domains are then classified into CATH families. This part of the protocol is called HomCheck. As with DomChop, any domains that cannot be automatically classified are manually curated. Dark gray boxes denote production of metadata, diamond-shaped boxes workflow decisions, and light gray boxes manual curation. Definitions of abbreviations and terms used are as follows: NW(Needleman–Wunsch sequence alignment algorithm); HMM (hidden Markov model); ChopClose (program that determines domain boundaries based on sequence identity with CATH domains); and CATHEDRAL (structure comparison program).

IDENTIFICATION OF DOMAIN BOUNDARIES

In the January 2007 release of CATH, over35% of PDB entries were multidomain proteins, of which two thirds comprise only two domains. Furthermore, nearly one third of domains in CATH are discontinuous, that is, the domain is formed from discontinuous segments of the polypeptide chain. It is well established that domains are known to recur in different multidomain contexts and that domain shuffling is a common evolutionary mechanism often responsible for creating new or modified functions within an organism (see Todd et al. (2001) and Teichmann et al. (2001) for reviews). Recent analysis of CATH revealed that at least 70% of the domains from multidomain proteins recurred in different multidomain families or also as single-domain proteins.

Identification of domain boundaries is a difficult process and most have an error rate of between 20% and 30% associated with them, although numerous automatic algorithms have been devised (see Chapter 20, Jones et al. (1998), and Veretnik et al. (2004)). The problem arises from the fact that no simple quantitative definition of a structural domain exists. Qualitatively, domains have been described by various authors as compact semi-independent folding units and many algorithms attempt to locate them by searching for large hydrophobic clusters indicative of domain cores and by dividing structures to maximize internal residue contacts within putative domains while minimizing external contacts between them.

During the CATH classification, any protein unassigned by the automatic sequence-method ChopClose (see above) are analyzed by several algorithms, first to delineate their domains and second for homology identification. CATHEDRAL and HMMscan (see below) are run to detect sequence and structural relatives of domains already in CATH, and the DBS suite runs three independent automatic domain definition programs. These comprise PUU (Holm and Sander, 1994), Domak (Siddiqui and Barton, 1995), and DETECTIVE (Swindells, 1995) (see Jones et al. (1998) for a description of methods). The data derived from these algorithms are displayed on the “domain chopping” page for that chain, along with relevant literature and assignments from other family classifications (e.g., Pfam). The curator is then able to make an informed decision on the most appropriate domain boundaries. Domain boundaries for a chopped chain in the CATH database can be seen on the page for that chain on the CATH Web site (see http://www.cathdb.info/cgi-bin/cath/Chain.pl?chain_id=1o7jA for an example).

Any ambiguous assignments can be manually validated by coloring putative domains in the excellent molecular viewing package, RASMOL (Sayle and Milner-White, 1995). The majority of domain assignment errors can be found in this way, although in difficult cases, boundary identification is a somewhat subjective process as witnessed by the fact that about 20% of boundary definitions in the SCOP and CATH databases disagree. This step is one of the most time consuming but important stages in the classification. Although domain boundary detection from structural data is difficult, it is considerably easier than assignment from sequence data and many sequence databases now incorporate the SCOP and CATH boundaries or use them to validate their own assignments.

METHODS TO DETECT SEQUENCE AND STRUCTURAL RELATIVES

Identifying Distant Homologues

Having determined domain boundaries, homology assignment for the constituent domains is undertaken. Profile-based methods are used as these can detect even very distant homologues. In these approaches, a sequence is scanned against a large sequence database (e.g., GenBank at the NCBI) initially using pair-wise methods to find close homologues, which are then multialigned to derive a sequence profile capturing the most specific residue preferences of the sequence and its relatives. Further iterations can result in highly specific profiles for the family to which the sequence belongs.

A number of protocols have been implemented based on hidden Markov models (HMMs). The SAMT method of Karplus et al. (1998) has been used to build profiles for each nonidentical representative in CATH and also for functionally coherent families within the database. New structures are therefore scanned against both SAMT profiles for representative structures already classified in CATH. For example, there are currently over 7000 SAMT profiles, including those built from individual domains and those generated from multiple alignments of functionally related proteins.

A protocol (Samosa) exploiting models built using multiple structural alignments to improve accuracy gives some improvement in sensitivity (4-5%). However, a protocol exploiting an eightfold expanded HMM library based on sequence relatives of structural domains derived from sequences in GenBank gives an increase of nearly 10% in sensitivity. HMM-HMM, profile-profile-based approaches have also been implemented using the PRC protocol of Madera and coworkers. These allow recognition of extremely remote homo-logues, some of which are not easily detected by structure comparison methods (discussed later). HMM-based scans developed for the CATH classification protocol are collectively referred to as HMMscan.

Profile-based methods enable nearly 15% of very distant homologues (<35% sequence identity) to be detected. This percentage will increase as the sequence databases, and therefore the intermediate sequence libraries within CATH, continue to grow with the international genome projects.

STRUCTURE-BASED METHODS FOR IDENTIFYING STRUCTURAL HOMOLOGUES AND RELATED FOLDS (SSAP AND CATHEDRAL)

A significant proportion (~20%, currently) of very distant relatives can only be recognized by comparing their structures directly. There are now many examples of evolutionary relatives that have diverged to an extent where no significant sequence similarity can be detected and yet the structural fold adopted by the protein remains highly similar. For example, the globins sequence identities of relatives can fall below 10% but the structures and oxygen binding functions of the proteins remain highly conserved. As with sequence alignment, any method for comparing distant structural relatives must be able to cope with the extensive insertions or deletions occurring during evolution. These are usually restricted to the loops between secondary structures where they are less likely to affect the fold and therefore the stability of the protein.

A recent analysis of CATH families (Reeves et al., 2006) found that on average, at least 50% of the secondary structures in the core of the protein are structurally well conserved across a family. However, in some families secondary structures and sometimes quite large supersecondary motifs can be inserted or deleted. In the most extreme cases, some related domains have a fivefold difference in size. In addition to residue insertions and deletions, shifts in the secondary structures can also occur to modulate the effects of volume changes caused by residue substitutions. Chothia and Lesk (1986) demonstrated quite significant movements of up to 40° in some secondary structure pairs for two large protein families studied (the globins and the immunoglobulins). Although recent analyses of CATH families showed that most secondary structure orientations (>60%) vary by up to 10°, significant numbers of secondary structures (~40%) have been observed to vary more than this and some superfamilies tolerate up to 80° in variation.

Overall the CATH analysis showed that although the core structural motif of protein folds is well conserved, significant structural embellishments to this core and shifts in secondary structure orientation can be found in about 2% of CATH families that are highly recurrent in the genomes. Sometimes these evolutionary changes give rise to modified or diverse functions within the family.

SSAP—SEQUENTIAL STRUCTURE ALIGNMENT PROGRAM

To cope with these structural variations, Taylor and Orengo adapted the dynamic programming methods used so successfully in sequence alignments to compare 3D structures (see Orengo (1994) for a detailed description and review ofapplications). Instead ofcomparing residue identities, the method compares the structural environments of residues between two proteins. These can be simply encoded as the set of vectors from the Cp atom of a particular residue to the Cp atoms of all other residues within the same protein. Since there is no prior knowledge of which residues are equivalent between the proteins, dynamic programming must be applied at two levels; a lower level in which the structural environments of all residue pairs between the proteins are compared and an upper summary level in which information from putative equivalent pairs are accumulated. The method is therefore sometimes described as double dynamic programming.

SSAP has been benchmarked and optimized using sets of validated structural homo-logues. The implemented logarithmic scoring scheme was optimized to be largely independent of the size and class of the proteins, although proteins with large proportions of alpha helices tend to give slightly higher scores as the local similarity is so highly conserved. The score is normalized to be in the range of 0-100 for identical proteins, irrespective of size and structures with similar folds tending to give scores above 70, while homologous proteins often give higher scores of 80 and above. Once two structures have been aligned, they are also superposed using the ProFit implementation of rigid body superposition (see Table 18.2) and a normalized RMSD calculated (RMSD x size of the largest domain structure/number of residues aligned). Both scores are used to assess the degree of structural similarity and determine whether the structures are likely to be homologous.

CATHEDRAL—CATHS EXISTING DOMAIN RECOGNITION ALGORITHM

Although SSAP has proven to be reliable and robust, giving extremely accurate structurally based residue alignments, it is computationally expensive and large structures such as TIM barrels with more than 300 residues that can take several days to scan against the database, even with the most powerful machines currently available. Although this has not proved to be a major bottleneck to date, structure genomics initiatives are expected to substantially increase the numbers of structures determined annually. Currently, over 100 new structures are determined weekly and this may double or treble over the next decade. Therefore, to keep pace with structure genomics, a novel algorithm has been designed that combines the robust residue-based structural alignment method of SSAP with a fast secondary and tertiary structure comparison algorithm based on graph theory. Graph theory had previously been implemented in the fast structural comparison algorithm such as POSSUM designed by Artymiuk and coworkers (Grindley et al., 1993).

The method implemented in CATH—CATHEDRAL (CATHs Existing Domain Recognition Algorithm) compares secondary structures between proteins, as there is an order of magnitude fewer of these than residues. These are represented as linear vectors and are associated with nodes in a protein graph. Edges between the nodes are characterized by the orientations of the secondary structures and the distances between their midpoints. Additional angles are used to describe the tilt and rotations of the vectors. Ullmans subgraph isomorphism algorithm is used to detect corresponding structural motifs between proteins, from comparison of their graphs. Parameters for recognizing fold similarities have been optimized using validated relatives from CATH.

A graph for each new entry is scanned against a graph for each of the existing domains in CATH. If a putative domain is identified, the domains are then aligned using the SSAP algorithm. A support vector machine is used to combine different scores that account for similarities in the size, class of the domains being compared, and the structural environments of equivalent residues. The combined scores are then used to select the best fold match for each putative domain and benchmarking experiments show that CATHEDRAL outperforms many equivalent approaches by recognizing the correct fold as the top match in a database scan 94% of the time. CATHEDRAL is also used in the preliminary stages of classifying new structures in CATH to recognize domains within multidomain structures and identify their boundaries. Benchmarking on a data set of nonredundant multidomain proteins has shown that at least 80% of domain boundaries could be recognized within ±15 residues, which compared with a 40% success rate for the most sensitive HMM-based protocols.

METHODS FOR GENERATING MULTIPLE STRUCTURE ALIGNMENTS (CORA) AND PROTOCOLS FOR USING 3D TEMPLATES USED TO IDENTIFY DISTANT STRUCTURAL RELATIONSHIPS

Multiple structure alignments are generated for each superfamily in CATH using a modified version of the SSAP algorithm (CORA—COnsensus Residue Attributes). This is based on progressive alignment of relatives using a single-linkage tree derived from the pair-wise SSAP similarity scores (see Orengo (1994) for a more detailed description). The most similar structures are aligned first and the next relative, most similar to the aligned structures, is then iteratively selected and aligned in the order dictated by the tree. After addition of each relative, a consensus structure is derived consisting of average vectors between residue positions and information on the variability of these vectors. Further relatives are aligned against this consensus structure, weighting the alignment of conserved positions more highly.

Once all relatives have been aligned, information on the conservation of the residue structural environment, including residue contacts, and various other attributes (e.g., accessibility, torsional angles) is compiled and encoded in a 3D template representing the set of structures. In a manner analogous to the improvements obtained using sequence profiles, structural templates have been shown to be more effective at recognizing distant homologues as they capture the most conserved structural characteristics of the family or superfamily. New structures can be scanned against libraries of CORA templates again using the double dynamic programming algorithm and the percentage of highly conserved contacts associated with the superfamily is calculated for the putative relative to determine homology. The pattern of conserved residue contacts has been shown to be a highly characteristic topological fingerprint for a particular superfamily.

CORA templates have been generated for each superfamily containing two or more nonidentical structures and multiple templates have been generated for each cluster of more closely related structures or families within more populated superfamilies. Scanning against the template library increases recognition performance of up to 100 times faster than performing pair-wise searches with SSAP on representative structures from the super-families. The templates also show increased sensitivity and selectivity over the pair-wise SSAP and this can be expected to increase as more structures are determined and coverage within each superfamily increases.

SEQUENCE, STRUCTURAL, AND FUNCTIONAL VALIDATION OF HOMOLOGY

As with domain assignment, homology assignment is a crucial part of the classification process and is manually validated. Results from all the sequence and structure comparison algorithms (HMMscan, SSAP, CATHEDRAL) and functional information from the literature and other family databases (e.g., Pfam) are collated and displayed on an internal webpage to aid the manual curation process. Both fold and homology assignments can then easily be confirmed from these data.

Protocols are currently being devised for automatic comparisons of functional annotations between proteins to speed up the validation of homologues during classification. For some very remotely related homologues, confidence in an assignment can be improved by combining information from multiple prediction methods. We have investigated the benefits of machine learning methods to do this automatically. A neural network was trained using a data set of 14,000 diverse homologues (<35% identity) and 14,000 nonhomologous pairs that have been collected using different homologue comparison methods including structure comparison (CATHEDRAL, SSAP), sequence comparison (HMM-HMM), and information on functional similarity. The latter was obtained by comparing EC classification codes between close relatives of the distant homologues and using a semantic similarity scoring scheme for comparing GO terms, based on a method by Lord et al. (2003). On a separate validation set of 14,000 homologous pairs, 97% of the homologues can be recognized at an error rate of <4%.

We do not expect this approach to be viable for more than about 50% of new relatives, a result suggested by the performance of similar protocols employed by other groups, because this validation stage is time consuming and serves as another major bottleneck in the classification process. However, we expect the new algorithm to significantly improve the frequency of CATH releases.

THE DICTIONARY OF HOMOLOGOUS SUPERFAMILIES (DHS)

Sequence, structural, and functional data for each homologous superfamily in CATH are stored in a Dictionary of Homologous Superfamilies (DHS), which is also accessible over the web at the CATH resource. This was originally established in 1999 by Bray and updated in 2006. It now also contains all the sequence relatives for CATH superfamilies identified in GenBank. Information on pair-wise sequence relationships between all nonidentical structures in each superfamily, namely, sequence identities, and expectation values from PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) and SAMT are also stored.

There are also pair-wise structural alignments between all nonidentical structures in the superfamily. Plots of sequence identities versus structural similarity scores can be used to illustrate the structural plasticity observed within a given superfamily and highlight any obvious outliers that may indicate problems in the alignment. Structures within highly populated and structurally diverse superfamilies are also clustered into structural subgroups using multilinkage clustering and a threshold on the pair-wise SSAP structural similarity score of 85. CORA multiple structure alignments are generated for each superfamily and structural subgroup and can be viewed (see http://www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/dhs/). These are annotated in various ways: by residue identities or physicochemical properties, by secondary structure, and by PROSITE motifs. RASMOL viewers for multiple superpositions of relatives allow the 3D location of conserved sequence motifs to be easily identified. The multiple structural alignments are also displayed as 2DSEC plots in which secondary structures are drawn as circles (α-helices) and triangles (p-strands) so that common secondary structures can be identified and secondary structure embellishments unique to a particular relative or group of relatives can also be viewed.

THE GENE3D RESOURCE

A related CATH-based web resource, Gene3D (Yeats et al., 2006), uses the assignments of gene sequences from CATH superfamilies to provide structural annotations for completed genomes. The March 2007 release of Gene3D (v5.0) contains 248 complete genomes obtained from UniProt. For each gene within the genome, the location of gene regions that match individual structural domains from CATH superfamilies is shown.

Importantly, Gene3D contains increasing amounts of functional data for each super-family, including domain data from Pfam, metabolic pathway data from KEGG, functional annotation from COGs and GO, and protein-protein interaction data from MINT, IntAct, and MIPS. Links to the relevant CATH superfamily and DHS entries are also provided. Statistics are given on the distributions of superfamilies and fold groups identified within each genome, enabling comparison of fold and superfamily usage between genomes. Further information on Gene3D and the evolutionary insights that can be derived from the predicted CATH data are presented in Chapter 22.

THE CATH WEB SITE AND SERVER

CATH is available over the internet at the site shown in Table 18.1. The site can be used for browsing the hierarchy and there are representative MOLSCRIPT illustrations at each level together with links to other local resources (DHS, Gene3D, and PDBsum). Each level has its own unique numeric identifier, which is never changed although some numbers may disappear. For example, if new evidence suggests, two superfamilies should be merged.

Previously, CATH data were generated using a group of independent programs and flat files. Over the past few years, we have developed an updated protocol for CATH that is driven by a suite of programs with a central library and a Postgre SQL database system. A classification pipeline has been established that links in a completely automated fashion the different programs that analyze the sequences and structures of protein chains and domains.

TABLE 18.1. Description of Levels in the Classification at the Architecture Level

| Primary Classification Number | Description of Level |

| 1 | Mainly α |

| 2 | Mainly β |

| 3 | αβ |

| 4 | Few secondary structures |

| 5 | Multidomain proteins |

| 6 | Single-domain proteins classified by sequence but not structure |

| 7 | Ambiguous multidomain proteins whose domain boundary assignment requires |

| manual validation. Protein chains clustered by sequence methods | |

| 8 | New proteins classified by sequence methods |

| 9 | Chains from multichain domains classified by sequence |

A suite of webpages has recently been developed to aid in the manual curation stages of DomChop and HomCheck (see Table 18.2). These pages display all available metadata from the prediction algorithms used in these steps (e.g., ChopClose. CATHEDRAL, HMMscan). Information regarding relevant literature and other classification data such as Pfam are also shown.

As these pages can be universally accessed, they provide biologists with interim data on their protein chain and/or domains of interest before they are fully classified into the CATH database.

THE CATHEDRAL SERVER

Newly determined structures can be submitted to the CATHEDRAL server that scans the query against representatives from the database to determine the putative superfamily or fold group to which the structure belongs or whether the protein comprises one or more novel folds. Domain boundaries can be supplied by the user or will alternatively be determined automatically.

CATHEDRAL identifies the nearest fold group for each domain. Lists of structural neighbors are provided together with links to the appropriate superfamilies in CATH and the DHS. The user can also view superpositions of the structure with other relatives from the superfamily or fold group.

IS FOLD CLASSIFICATION A LEGITIMATE REPRESENTATION OF DOMAIN STRUCTURE SPACE?

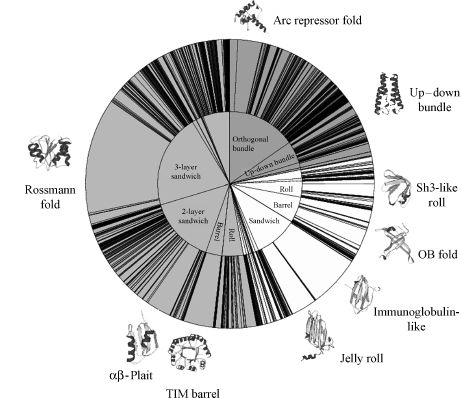

The universe of protein structures can be represented as a CATH wheel (Figure 18.4), derived by using one representative from each diverse sequence family (i.e., relatives clustered at 35% sequence identity). Using one representative is important as many homologous superfamilies have multiple redundant entries in sequence and structure databases, which can introduce considerable bias in the data if not treated correctly.

TABLE 18.2. URLs of CATH Domain Structure Database and Related Resources

| Resource | URL |

| CATH Database: Classification of structural | http://cathwww.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/latest/ |

| domains in the PDB. Domains are grouped | |

| by Class, Architecture, Topology (Fold), and | |

| Homologous superfamily. There are links to | |

| PDB sum | |

| SSAP Server: The SSAP server allows users to | http://cathwww.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/cath/SsapServer.pl |

| compare the structures of two proteins and | |

| view the subsequent structural alignment | |

| CATH Server: The CATH server allows users to | http://cathwww.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/cath/CathedralServer.pl |

| compare a PDB or novel structure against a | |

| representative library of structures in CATH. | |

| Dictionary of Homologous Superfamilies: This | http://www.cathdb.info/bsm/dhs/ |

| resource displays the structural alignments | |

| for all members of a homologous | |

| superfamily classified in the CATH database. | |

| The alignments are augmented with ligand | |

| information and SWISS-PROT annotations | |

| Gene3D: Database of precalculated structural | http://cathwww.biochem.ucl.ac.uk:8080/Gene3D/ |

| assignments for genes and whole genomes. | |

| The data are derived using PSI-BLAST and | |

| IMPALA | |

| IMPALA server: This server allows the user to | http://www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/cath/Impala/ |

| screen a sequence against the CATH set of | |

| IMPALA sequence profiles for protein | |

| structural domains |

This includes the HOMCHECK, DOMCHECK, and PROFIT web pages as well as the Madera PRC resource.

This includes the HOMCHECK, DOMCHECK, and PROFIT Webpages as well as the Madera PRC resource.

The distribution of families in the Protein Data Bank can be seen from Figure 18.4 showing that the current diverse sequence families of mainly α(26%), mainly β(22%), and αβ structures (48%) are distributed within 40 architectures. Twenty-eight of these architectures are well defined, and the remaining groups can be thought of as bins comprising assorted irregular or complex folds or folds containing few secondary structures that are often stabilized by disulfide bonds. Furthermore, among the well-defined architectures, some are much more highly populated than others and it can be seen from Figure 18.4 that about half of the folds adopt one of six regular symmetric architectures: the mainly α-bundles, the two-layer β-sandwiches and β-barrels, and the two- and three-layer αβ-sandwiches and αβ-barrels.

Recent analysis of the structural relationships between fold groups in CATH using the GRATH algorithm has revealed that some fold groups are particularly “gregarious.” That is, they have quite large motifs (up to 40% of the structure) in common with many other folds within the database. In particular, those folds containing common supersecondary structural motifs, such as β meanders, Greek keys, α-β plait motifs, or α-hairpins, match similar motifs in many other folds. α-β folds were found to be particularly gregarious, as were other folds found in the highly populated architectural regions of fold space (e.g., α-β plaits). This conforms to the idea of a structural continuum where in some regions of fold space there can be considerable overlap between different fold groups. Often it is difficult to distinguish between these folds and the definition of folds becomes somewhat subjective. It tends to be in these regions of fold space that structural classifications such as CATH and SCOP disagree.

Figure 18.4. CATH wheel plot showing the distribution of nonhomologous structures, that is, a single representative from each homologous superfamily (H-level in CATH) among the different classes (C), architecture (A), and fold families (T) in the CATH database. Protein classes shown are mainly alpha (dark gray), mainly beta (light gray), and alpha–beta (mid-gray). Within each class, the angle subtended for a given segment reflects the proportion of structures within the identified architectures (inner circle) or fold families (outer circle). The superfold families are indicated and are illustrated with a Molscript drawing of a representative from the family.

Domains that exhibit low gregariousness usually have very distinctive folds, for example, the β trefoil folds, and often comprise unusual motifs or motifs packed in unusual arrangements as in the superhelices. These folds are more representative of discrete islands rather than progressions in a structural continuum.

The idea of a structural continuum is perhaps not surprising as it has long been known that certain structural motifs are favored and often recur within folds for a particular class; for example, the β-hairpins and the beta Greek keys in the mainly β class, the α +β and α/αβ motifs in the αβ class (Richardson, 1981), the TIM barrel fold in the αβ class (see Figure 18.2 for a representative picture) comprises eight recurring αβ motifs, and these motifs are also found to recur in the αβ Rossmann folds (see also Figure 18.2), though the orientation between two of the motifs differs giving rise to a different topology for the fold.

In addition to considering the structural overlap between different fold groups, it is also interesting to consider the structural deviation or drift within an evolutionary superfamily as this is another mechanism causing overlap between fold groups in hierarchical classifications, such as CATH and SCOP. Recent analyses of CATH reveal that in most superfamilies, the domain relatives are structurally very similar to each other if the global structural similarity between domain structures is considered, that is, at least 60% or more of the larger domain is matched between two domains. However, there are some notable exceptions to this. Considerable deviations in structure can occur between relatives in a small percentage of families (<5%). Many Rossmann fold superfamilies (CATH code 3.40.50) have within them a significant number of protein domains that are very dissimilar to each other in terms of structure.

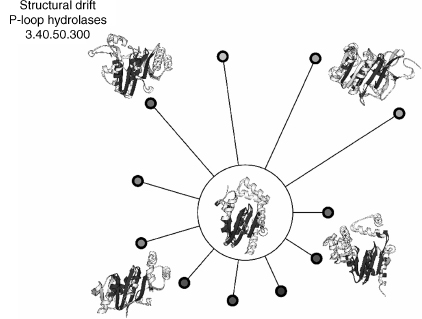

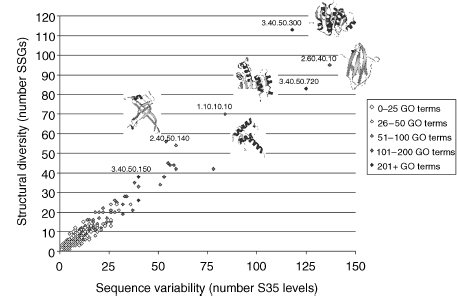

This phenomenon, which can be described as structural drift, is often caused by the insertions of extensive secondary structures outside the common structural core (see Figures 18.5 and 18.6). These insertions can be described as secondary structure embellishments (Reeves et al., 2006). Many families in which this phenomenon is observed are highly populated in the genomes (Figure 18.6). For example, superfamilies adopting the Rossmann fold are the most highly populated structural families in the genomes and paralogous domains have diverged considerably in structure (Figure 18.5). This structural divergence has been accompanied by extensive modification of the function and a total of 168 GO molecular function terms are currently associated with the Rossmann fold. Interestingly, those super-families most vulnerable to structural drift tend to belong to fold groups that have very regular architectures, for example, two-layer mainly β and two- and three-layer αβ architectures. These architectures appear to be particularly tolerant to secondary structural embellishments that tend to occur at the edges of the β-sheets where they cause little disruption to the overall fold.

Figure 18.5. Foldspin plot showing an example of structural drift for the Rossmann superfamily 3.40.50.300. Structural comparisons were made between the protein structure in the center of the wheel with other structures in the same superfamily; these are represented by spokes on the wheel. The length of each spoke correlates with the structural similarity score between the two structures; the more similar the structures, the shorter the spoke. The structure for which all comparisons are made and some of these structures it is compared against are shown as molscripts; the dark gray regions highlight the structural features common to both structures and the light gray regions indicate where differences occur. It can clearly be seen that although there is a common structural “core,” there are also some significant variations.

Figure 18.6. Relationship between sequence variability, structural variability, and functional diversity in CATH superfamilies. Structural variation in a CATH superfamily as measured by the number of diverse structural subgroups (SSAP score <80 between groups) is plotted against sequence diversity as measured by the number of sequence diverse subfamilies in the CATH-DHS (<35% sequence identity between groups). The color of each point reflects the number of functions identified in that superfamily using GO as follows: white (0-25), light gray (26-50), mid-gray (51-100), dark gray (101-200), and black (200 +).

Although structural overlaps between fold groups are frequently observed when small motif similarities are analyzed (i.e., comprising <40% of the larger domain), far fewer overlaps are detected when examining structural similarity at a more global level (>60% of larger domain). In fact, fewer than 10% of homologous superfamilies exhibit significant structural overlaps with domains in different fold groups. Although both structural drift and overlap at the global level occur in comparatively few superfamilies, it is important to note that these superfamilies tend to be the most highly populated in terms of the number of available structural domains and their prevalence in the genomes. Therefore, it is likely that the CATH classification will present neighborhood information as well as a strictly hierarchical grouping of structures in the future. For each domain structure, significant structural overlaps with domains in other superfamilies and fold groups are already presented in CATH.

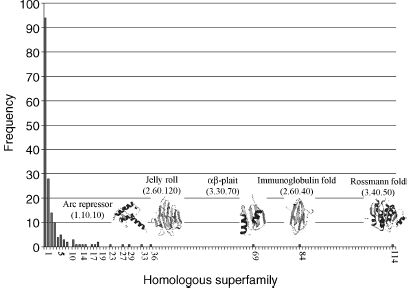

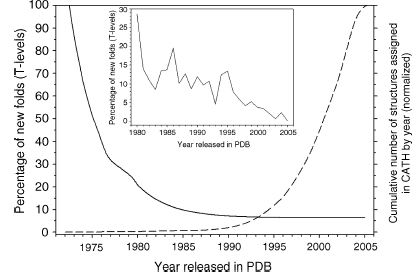

POPULATION OF SUPERFAMILIES AND FAMILIES WITHIN FOLDS

The current population of the different levels in the CATH hierarchy for the January 2007 release is shown in Figures 18.4 and 18.7, and the number of new folds being determined each year appears to be slowly decreasing (Figure 18.8). Early analysis of CATH revealed a small number of highly populated fold groups (~10) containing many different homologous superfamilies and families. A recent re-examination of these data shows a greater than 10-fold expansion of the database from 3000 to 35,000 domain structures, a continuing trend as reflected in Figure 18.4 showing eight large fold groups containing nearly one third of all the homologous superfamilies in CATH. These highly populated fold groups have been described as superfolds and other classifications (e.g., SCOP) have reported similar observations of frequently occurring domains (FODs) within the database.

Figure 18.7. Populations of different levels in the CATH hierarchy; homologous superfamilies within fold groups. CATH version 3.1 was used to generate the histograms.

Figure 18.8. Annual decrease in the percentage of new structures classified in CATH that are observed to possess a novel fold. The raw data for years 1972–2005 was fit to a single exponential equation by nonlinear regression using Sigma Plot (SPSS, version 9.0) and the fit is shown as a solid black line. The inset shows a close-up of the raw data for new topologies over the years 1980–2005. For comparison, the numbers of structural domains solved each year and deposited in the PDB and classified in CATH is depicted by the dashed line.

The popularity of these folds may be a result of divergent or convergent evolution. Divergent evolution gives rise to families of proteins in which the structure is generally well conserved but sequences may have changed to the extent that no significant similarity remains. In paralogs, which arise from duplication of the gene within an organism, the protein function may also have been modified or changed. Thus, the apparently diverse superfamilies within these superfolds may in fact be extremely distant relatives whose relationships cannot easily be verified from the available sequence or functional data.

Alternatively, Ptitsyn, Finkelstein, and others have suggested that there may be a limited number of folds in nature due to physical constraints on the packing of secondary structures. Chothia has suggested approximately 1000 folds and other similar estimates of a few thousand folds have also been made. Structures sharing the same fold but arising from different ancestral proteins have been described as analogues.

The task of determining homology is often complicated by the lack of evolutionary clues. Murzin and others have shown several interesting examples of relatives possessing similar folds but disparate sequences and functions. In these cases, homology has been suggested by the presence of rare structural characteristics, for example, a conserved i-bulge. Detailed knowledge of the structural family can often provide insights that promote detection of evolutionary fingerprints. However, such practices are not readily amenable to automated protocols. The TIM barrel fold is one of the most highly populated, with 18 superfamilies in a recent CATH release. However, several detailed studies have recently provided evidence of common ligand binding motifs or unusual structural characteristics suggesting that many of these superfamilies should be merged (Nagano, Orengo, and Thornton, 2002). When classifying new relatives in CATH, many types of evidence are manually considered during curation (e.g., matching sequence motifs, similarity in rare structural motifs, and clues about similarity in functional mechanisms) to try to improve the detection of very remote homologues. These data are presented to the curator on the HomCheck webpages (see Table 18.2) and are also available to biologists interested in a particular classification for a domain in CATH.

FOLD CLASSIFICATION IN CATH

When deciding how to classify folds and whether a structural continuum exists, it is important to consider the extent to which related proteins in a superfamily may have residue insertions or deletions that cause significant elaborations or alterations of the protein structure. Although some families such as the plekstrin homology domain and the lipocalins are structurally highly conserved and do not tolerate much deviation, other superfamilies contain structures that have changed dramatically between distant relatives not only in fold but also in architecture.

In these cases where more than one fold group can be identified within the superfamily, the hierarchical nature of CATH classification has broken down. At present, there are relatively few occurrences of these dramatic changes and they are documented on the CATH Web site as cross-hits (see Table 18.2). As more structures are elucidated so that fold space becomes more highly populated and as methods improve for detecting remote homologues, further examples of these extreme changes in fold may be identified.

TABLE 18.3. Names of the Researchers and Advisors Who Have Contributed to the CATH Database Since It Was Established in 1993

| List of Contributors (Alphabetical) | |

| Sarah Addou | Andrew Martin |

| Adrian Akpor | Alex D. Michie |

| Chris F. Bennett | Rekha Nambudiry |

| James E. Bray | Christine A. Orengo |

| Daniel W. A. Buchan | Frances M. G. Pearl |

| Alison Cuff | Kanchan Phadwal |

| Tim Dallman | Gabrielle Reeves |

| Beniot Dessailly | Adam Reid |

| Mark Dibley | Jane S. Richardson |

| Lesley Greene | Elisabeth Rideal |

| Andrew Harrison | Oliver Redfern |

| Gail Hutchinson | Adrian J. Shepherd |

| Azara Janmohamed | Stathis Sideris |

| Susan Jones | Ian Sillitoe |

| Roman Laskowski | Mark B. Swindells |

| David Lee | Wille R. Taylor |

| Jon Lees | Janet M. Thornton |

| Loredana Lo Conte | Annabel E. Todd |

| Russell Marsden |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all those who have contributed to the massive undertaking of this resource (Table 18.3)