21

INFERRING PROTEIN FUNCTION FROM STRUCTURE

INTRODUCTION

The Importance of Predicting Protein Function from Structure

The various genome-sequencing projects around the globe have provided us with massive amounts of information detailing all the genes in a number of organisms required for survival. The amount of sequence data is set to rapidly expand as a result of the very large-scale metagenomics projects such as the Global Ocean Survey (Yooseph et al., 2000). By comparison, the protein structure data falls far behind. Structural genomics aims to close the gap by experimentally determining a large number of protein structures as rapidly and accurately as possible using high-throughput methods. There are several consortia working on this across the globe and each has its individual goals, but one of the key aims is to increase the coverage of protein fold space and hence the proportion of protein sequences amenable to homology modeling methods. As a result, an increased number of protein structures have been released with little or no functional annotation. This is a reversal of the usual experimental investigation of proteins, which involves taking a protein of interest, carrying out biochemical experiments to determine functional information about it, and then using the structure to rationalize this functional information (Thornton et al., 2000). For example, the tyrosine kinases were known to be signaling molecules long before the crystal structure revealed molecular mechanisms of their function (Hubbard et al., 1994). The recent ramp-up of structural genomics projects to full-scale production and investment in new technologies to address the more challenging problems of complexes and membrane proteins means that the numbers of structures deposited in macromolecular structure databases will continue to rise. One of the major goals in modern bioinformatics is the development of computational methods to accurately and automatically assign functions to these proteins.

Definition of Function

The function of a protein is not always well defined (Skolnick and Fetrow, 2000) and can be described at a number of levels: from highly specific enzyme reactions to biochemical pathways and up to the organism as a whole. The problems are compounded by the fact that a protein’s function can vary as a consequence of changes in expression and environment (Jeffery, 1999). Oligomerization and cellular localization are examples of such changes. Phosphoglucose isomerase acts as a neuroleukin, a cytokine and a differentiation and maturation mediator in its monomeric, extracellular form, but as a dimer inside the cell, it has a role in glucose metabolism, catalyzing the interconversion of glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate. Different experimental techniques can elucidate these different aspects of function and therefore there is a great deal of inconsistency in the specificity of annotations.

In order to catalog the diversity of functions adopted by proteins, much work has been done to standardize functional descriptions. The most well-known being the Enzyme Commission (EC) numbering scheme (http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/). This is a four-level hierarchy that classifies different aspects of chemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes. The first digit denotes the class of the reaction, and subsequent levels classify the substrate, the type of bond involved, cofactors, and other specificities (Table 21.1).

TABLE 21.1. Description of the Different Levels in the EC Classification

An enzyme reaction is assigned a four-digit EC number, where the first digit denotes the class of reaction. Note that the meaning of subsequent levels depends on the primary number; for example, the substrate acted upon by the enzyme is described at the second level for oxidoreductase, whereas it is described at the third level for hydrolase. Different enzymes clustered together at the third level are given a unique fourth number, and these enzymes may differ in substrate/product specificity or cofactor dependency, for example. Note that the EC is a classification of overall enzyme reactions and not enzymes.

TABLE 21.2. Gene Ontology Functional Classifications

| Category | Description |

| Biological process | A biological objective to which the gene product contributes. A process (which often involves a chemical or physical transformation) is accomplished via one or more assemblies of molecular functions. A biological process can be high level (or less specific), for example, cell growth and maintenance, or low level (or more specific), for example, glycolysis. |

| Molecular function | The biochemical activity of a gene product, describing what it actually does without alluding to where or when. A molecular function can be broad (or less specific), for example, enzyme, or narrow (or more specific), for example, hexokinase. |

| Cellular component | Refers to the place in the cell where a gene product is active |

The EC nomenclature is limited to enzymes and has problems when dealing with multifunctional proteins such as methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase. This protein catalyzes the conversion of methylenetetrahydrofolate to formylfolate in two separate reactions that are thought to proceed using the same or overlapping active sites (Allaire et al., 1998). This enzyme has two EC numbers associated with it: 1.5.1.5 and 3.5.4.9.

A more recent development has been the Gene Ontology (GO) scheme (http://www.geneontology.org, Ashburner et al., 2000), which attempts to standardize the description and definition of biological terms through three structured, controlled vocabularies. The three major sections are Cellular Component, Biological Process and Molecular Function (see Table 21.2). GO has become one of the most commonly used ontologies in bioinformatics and has three key advantages: it uses a controlled vocabulary, is an open source, and is machine-readable. The last feature makes it ideally suited for use in automated comparison and function prediction servers. The one problem is that it is not a linear hierarchy and therefore the relationship between gene product and biological process, molecular function, and cellular component is often one to many, making direct comparisons more complicated. The main advantage is that, by separating and independently assigning these attributes, relationships between gene product and function can be clarified more easily.

WHAT INFORMATION CAN BE OBTAINED FROM THREE-DIMENSIONAL PROTEIN STRUCTURES?

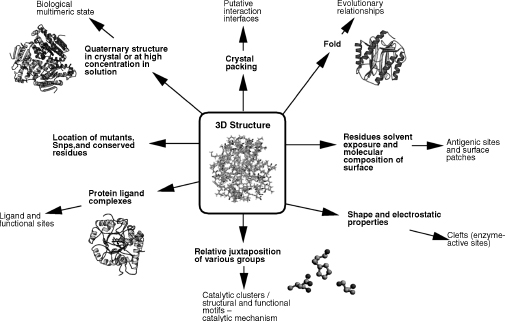

The basic structure comes in the form of a Protein Data Bank (PDB) file (Berman et al., 2000), which is a list of 3D coordinates of all the atoms in the protein. The PDB file itself contains little, if any, functional data. There is sometimes a ’SITE’ record, but this is used for various purposes such as ligand binding sites, metal binding sites, and ’active sites’ and is not consistent. As discussed previously, many PDB files contain no functional information and many of the structural genomics deposits are labeled only as “hypothetical protein.” However, from the structure we can derive information related to biological function; this information is summarized in Figure 21.1.

Figure 21.1. From structure to function: a summary of information that can be derived from three-dimensional structure, relating to biological function.

Starting at more coarse general observations, we can see the quaternary structure present in the crystal, which can tell us the oligomeric state of the protein, and may throw light on protein-protein interactions. We can then identify buried residues making up the core of the protein and residues on the surface exposed to the solvent. By looking more closely, we can also see the shape and molecular composition of the surface, clefts and pockets, and finally the arrangement of amino acid side chains and the juxtaposition of individual groups.

INFERRING FUNCTION FROM STRUCTURE

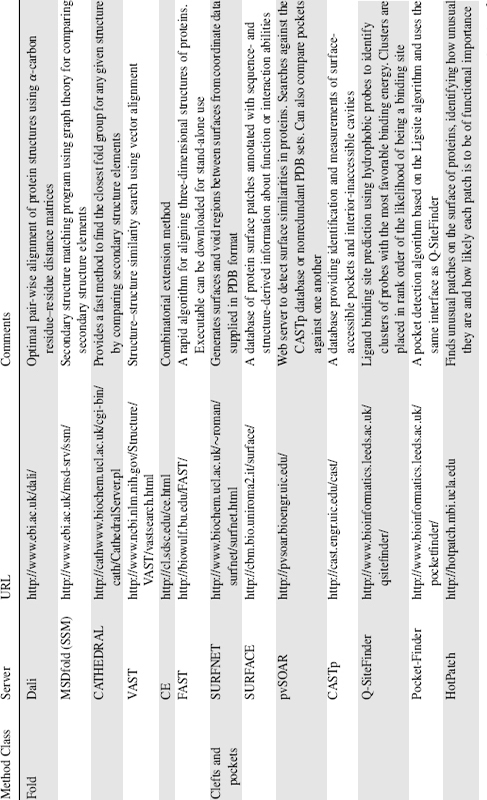

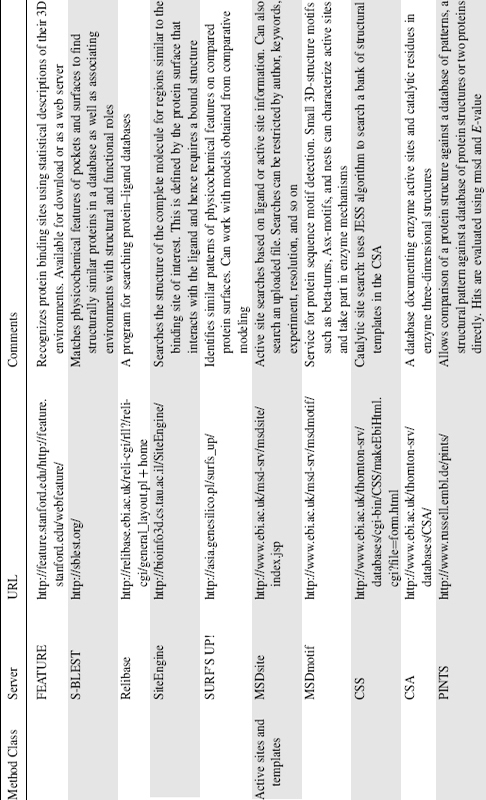

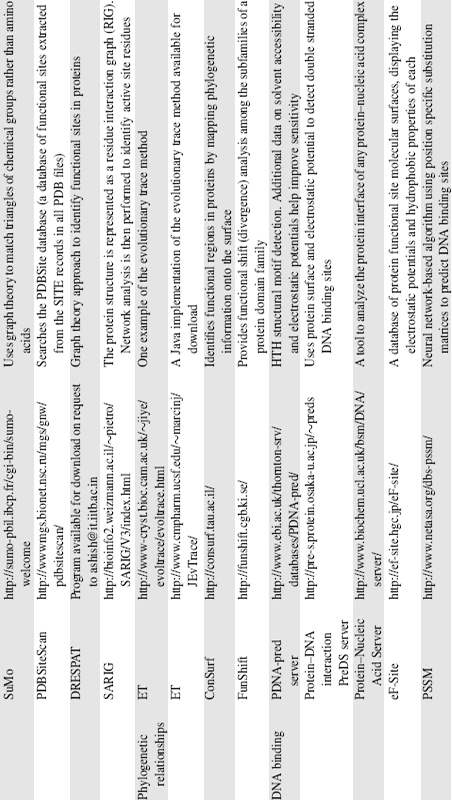

Computational methods to infer a function of an individual protein, such as its enzymatic activity, generally fall into two main types: those that are sequence-based and those that are structure-based. The different structure-based methods are discussed individually below and example servers (with web links) are detailed in Table 21.3. The sequence-based approaches are usually the first port of call as significant similarities in sequence can provide strong indication of function. It has been shown (Todd, Orengo, and Thornton, 2001) that above 40% sequence identity, homologous proteins tend to have the same function; but below this threshold, conservation of function falls rapidly, although there are always exceptions to this rule (Whisstock and Lesk, 2003) and if the domain composition is retained, function can be inferred at even lower sequence identities (Orengo, 2007). The most commonly used sequence-based methods involve BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) or FASTA (Pearson, 1991) runs to perform direct sequence-sequence comparisons of the protein sequence against large sequence databases such as UniProt (Apweiler et al., 2004) or GenBank (Benson et al., 2005) in order to identify similarity with proteins of known function. More powerful and sensitive profile/pattern-based methods, such as those using hidden Markov models, have been developed to identify very distant relationship . These model can be constructed from sequence in whole protein families where the family is defined by a similarity threshold using their 3D structure (e.g., Gene3D (Yeats et al., 2006) and SUPERFAMILY (Gough and Chothia, 2002), or in terms of sequence similarity and function (e.g., Pfam; Sonnhammer et al., 1998).

TABLE 21.3. Commonly Used Servers for Predicting Protein Function from Structure, Grouped by Type of Method

Other aspects of proteins that can be analyzed to provide functional clues include phylogenetic profiles, residue conservation patterns, genome structure, and gene location. However, when the sequence-based methods fail or provide few functional clues, examining the protein’s 3D structure can provide further insight. The structure-based methods can be classified according to the level of protein structure and specificity at which they operate, ranging from analysis of the global fold of the protein down to the identification of highly specific 3D clusters of functional residues (Stark and Russell, 2003; Laskowski, Watson, and Thornton, 2005). The underlying strategies for functional annotation of proteins using structural information are highlighted in the following sections.

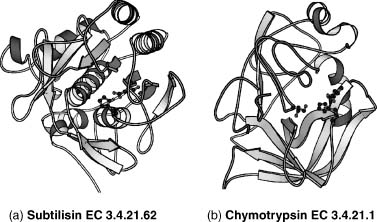

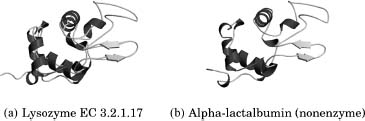

Fold Matching

Within defined bounds, we can compare the structure of a protein of unknown function with the structures of proteins of known function in structural databases such as CATH (Orengo et al., 1997) or SCOP (Lo Conte et al., 2000) to inherit the functional information from the closest match. This is usually the first step in assigning function from structural information as proteins with a similar structure and sequence identity are evolutionarily related and likely to share a similar function. However, caution must be exercised in transferring function from one homologous protein to another. If two proteins share local structural similarity but do not share any sequence identity, this may be the result of convergent evolution such as in the classic example of subtilisin and chymotrypsin that have no sequence similarity and have very different folds (as shown in Figure 21.2) yet are found to have an identical Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad and can also be inhibited by the same enzyme inhibitors (Henschel, Kim, and Schroeder, 2006). This serves as an example where the use of global protein features at the sequence and structural level may preclude functional annotation that can only be observed using local structural comparisons. The opposite is also true when two structurally homologous and evolutionarily related proteins have different functions, the classic example being that of lysozyme and a-lactalbumin (Acharya et al., 1991). These two proteins have high sequence identity between them but vary in their function (Figure 21.3).These types of problems are very difficult to identify in an automated manner and as a consequence are usually identified by manual assessment of the predictions through experiment. Improvements in high-throughput experimental functional assays (Kuznetsova et al., 2005; Proudfoot et al., 2004) and mass ligand binding screens (Vedadi et al., 2006) may help detect these errors in a large-scale data analysis, but problems can be avoided in the first place through careful annotation of function on a case-by-case basis.

Figure 21.2. Subtilisin and chymotrypsin are both serine endopeptidases. They share no sequence identity, and their folds are unrelated. However, they have an identical, three-dimensionally conserved Ser–His–Asp catalytic triad, which catalyzes peptide bond hydrolysis. These two enzymes are a classic example of convergent evolution.

Figure 21.3. Lysozyme and α-lactalbumin share 40% sequence identity between them, and similar structures, but they have different functions. Lysozyme is an O-glycosyl hydrolase, but α -lactalbumin does not have this catalytic activity. Instead, it regulates the substrate specificity of galactosyl transferase through its sugar binding site,which is common to both α -lactalbumin and lysozyme. Both the sugar binding site and the catalytic residues have been retained by lysozyme during evolution, but in α -lactalbumin, the catalytic residues have changed and it is no longer an enzyme.

Several methods exist for fold searching, the best known being DALI (Holm and Sander, 1995). Some popular methods used by the research community include MSDfold (SSM; Krissinel and Henrick, 2004) and CATHEDRAL (Pearl et al., 2003), both of which use graph theory to match secondary structure elements. Other approaches use different algorithms to match structures: VAST uses vector alignment of secondary structures, CE (Shindyalov and Bourne, 1998) uses combinatorial extension, and FAST (Zhu and Weng, 2005) uses a directionality-based scoring scheme to compare intramolecular residue-residue relationships. All of the methods, generally speaking, agree when assessed with the same data set but major disagreements can be a problem so the best approach is to use two or three methods to identify the consensus match (for a review of fold comparison servers see Novotny, Madsen, and Kleywegt, 2004).

Surface Clefts and Binding Pockets

One of the main factors determining how a protein interacts with other molecules is the size of clefts on the protein surface. Clefts provide an increased surface area from which the solvent may be excluded and therefore an increased opportunity for the protein to form complementary hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts with small ligands.

A protein ligand binding site (active site) is often found to be the largest cleft in the protein, and this cleft is often significantly larger than other clefts in the protein (Laskowski et al., 1996). The identification and analysis of surface clefts can therefore lead to a cofactor or ligand identification and hence putative functions for the protein are suggested. These surface clefts and pockets can be identified in a number of ways, but one of the most commonly methods used is the SURFNET algorithm (Laskowski, 1995), which detects gap regions within the protein by fitting spheres of a certain range of sizes between the protein atoms. Once clefts and pockets are identified, they can be compared against databases of known clefts to identify local similarities. The pvSOAR web server (Binkowski, Freeman, and Liang, 2004) allows searches to be performed against the CASTp database or against a nonredundant set of the PDB, returning statistically significant similar pockets to the user for detailed analysis.

A different approach to pocket identification is that of Q-SiteFinder (Laurie and Jackson, 2005) that uses the interaction energy between a protein and a van der Waals probe to find energetically favorable binding sites. This method is more effective than a more geometric method, Pocket-Finder, at identifying pockets that accurately overlap with bound ligands.

The analysis of the physicochemical properties of protein local environments is key to understanding protein-ligand interactions and the chemistry of active sites. As such a number of different methods have been developed to compare physicochemical features of pockets and surfaces. One such approach, FEATURE (Bagley and Altman, 1995), creates descriptions of the localized microenvironments using a variety of physical and chemical properties from detailed atomic or chemical groups, up through residue-specific properties to secondary structure level. This type of representation is used by another program, S-BLEST (Mooney et al., 2005), to rapidly search databases containing vectors of local structural properties. The matched environments can be used to find structurally similar proteins in a database as well as associating environments with structural or functional roles.

A new method developed by Najmanovich and coworkers (Najmanovich et al., 2007) uses physicochemical properties in a slightly different way as part of a two-stage graph-matching process. The first stage involves an initial superimposition by identifying the largest clique in an association graph constructed using only the Ca atoms of identical residues in the two clefts. In the second stage, all nonhydrogen atoms are used and the resultant transformation matrix allows an all atom superposition on the two clefts. One of the greatest advantages to the approach is that, by considering all non hydrogen atoms, it can use large sets of atoms as an input that allows the analysis of large, over predicted, and apo form binding sites.

Two other physicochemical approaches are those of SiteEngine (Shulman-Peleg, Nussinov, and Wolfson, 2004) and the recently released “SURF’S UP!” service (Sasin, Godzik, and Bujnicki, 2007). SiteEngine takes a different view of binding sites from that of FEATURE; instead of utilizing various levels of environmental properties, it represents residues as pseudocenters of any given physicochemical property. This allows a rapid comparison and site matching using a geometrical hashing technique. “SURF’S UP!” is another method that identifies similar patterns of physicochemical features on compared protein surfaces, its unique aspect being that it returns a “spherical coordinates” representation of the proteins (in PDB format) and an associated graphical image. In addition to this, the service returns a matrix of the values of similarities between the surfaces and a clustering of similar surfaces. The key advantage of the method is that it uses coarse-grained surface features that can be used on comparative models. This is especially relevant in the context of structural genomics in which one goal is to solve enough structures to allow entire genomes to be modeled by homology.

A powerful new method (Morris et al., 2005) for comparing ligand binding pockets uses spherical harmonics to essentially reduce the pockets to unique strings of integers, allowing rapid comparisons to be made. An analysis using this method (Kahraman et al., 2007) identified “buffer zones” in binding pockets filled with water. It is believed that these regions may allow the conformational flexibilities of the ligand and the protein when in the bound state or may even allow the binding of metals alongside the ligand. This suggests that much is still to be learned about ligand-protein recognition.

Care should be taken when attempting to infer function from binding site similarity as demonstrated by an analysis of human cytosolic sulfotransferases (Allali-Hassani et al., 2007). The study found that although proteins with similar small-molecule binding profiles tend to have a higher degree of binding site similarity, and small molecules with similar protein binding profiles tend to be topologically similar, the similarity is not enough to allow one to predict the small-molecule binding patterns.

Residue Templates

The three-dimensional arrangement of enzyme active-site residues is often more conserved than the overall fold, a classic example being that of the catalytic triad where a serine, histidine, and aspartate show a highly conserved geometry essential to their catalytic function. The identification of such structural motifs can be used to identify functionally important local similarities in proteins with different folds. A variety of approaches have been developed to identify these local geometric patterns of residues or atoms in protein structures.

TESS stands for template search and superposition, and is a geometric hashing algorithm for deriving three-dimensional template coordinates from structures deposited in the PDB (Wallace, Borkakoti, and Thornton, 1997) but has been superseded by the rapid JESS algorithm (Barker and Thornton, 2003). The templates used by TESS and JESS can be derived manually by mining the primary literature and assessing which residues form the active site, or they can be generated automatically. The Catalytic Site Atlas (Porter, Bartlett, and Thornton, 2004) was originally a database based on manually curated templates but has recently been automatically expanded to include homologues identified by PSI-BLAST, and a new web server (Catalytic Site Search) allows users to query the database directly using the JESS algorithm. Other template-centric approaches include fuzzy functional forms (FFFs; Fetrow and Skolnick, 1998) and SPASM/RIGOR (Kleywegt, 1999). The key difference between these two methods is that FFF uses the distances between alpha carbons (with a small variance) instead of 3D-atomic coordinates whereas SPASM/RIGOR uses C-alpha and side chain pseudoatoms as its template.

As mentioned earlier, templates can be generated automatically and there are several examples of methods that use these. PDBSite Scan (Ivanisenko et al., 2004) uses the SITE records in the PDB files and protein-protein interaction data from heterocomplexes to generate their templates. DRESPAT (Wangikar et al., 2003) is a graph theory approach to detect recurring three-dimensional patterns in the known protein structures. This approach has the advantage of being a fully automated process but can miss biologically significant motifs if they are uncommon. SuMo (Jambon et al., 2003) is quite similar in many ways with the major exception that it uses “stereochemical groups” instead of amino acids for its searches.

A different approach is shown by the PINTS (Patterns in Nonhomologous Tertiary Structures) server (Stark and Russell, 2003). Rather than operating on a preformed template, PINTS detects the largest common three-dimensional arrangement of residues between any two structures, the assumption being that a similar arrangement of residues implies similar function.

Phylogenetic Relationships

In general, functionally important areas on protein surfaces such as active sites are more highly conserved than surrounding regions. There are numerous methods to identify pockets and clefts and compare physicochemical features, but these approaches can be improved further by taking into account the residue conservation. There are a variety of methods available to calculate raw residue conservation scores from sequence alignments, but more powerful approaches take into account conservation over evolutionary time. The most popular of such methods is the evolutionary trace (ET) approach (Madabushi et al., 2002), which combines the use of a phylogenetic tree to rank residues in a protein by their evolutionary importance and structural mapping of these residues for functional inference based on clustering at the surface. It is observed that those with the highest rank tend to cluster on the protein surface in functionally important sites. A number of servers have been set up to offer the ET method and there is also a Java implementation (JevTrace) that can be downloaded (Joachimiak and Cohen, 2002).

ConSurf (Glaser et al., 2003) is another evolutionary approach that automatically generates a multiple sequence alignment (or uses one supplied by the user), creates a phylogenetic tree from this alignment, calculates the degree of conservation, and finally maps this onto the structure. This approach is useful for identifying regions of variability as well as conservation, which can be important when investigating proteins that interact with many effectors. ConSurf has recently been combined with SURFNET to enable the reduction in size of predicted clefts to only the most evolutionary conserved regions (Glaser et al., 2006). This approach shows that the largest clefts remaining after the reduction tend to be those where ligands bind.

One problem with mapping conservation onto the surface is that it relies on there being sufficient homologues in the sequence databases. Many new structures have little or no sequence relatives and therefore the ability to detect conserved surface patches or interfaces is poor. The protein interface recognition (PIER) method (Kufareva et al., 2007) aims to solve this problem by predicting a protein’s interfaces from structure using local statistical properties of atoms on the protein surface.

DNA Binding Prediction

One important aspect of protein function involves nucleic acid binding. It has been known for sometime that a limited repertoire of key structural motifs exists to recognize DNA (Harrison, 1991). The most common motif is the helix-turn-helix (HTH) where the recognition helix lies in the major groove of the DNA, but there are various subfamilies and elaborations on this theme such as the winged-HTH motif (Aravind et al., 2005). The problem with the structural motifs is that they occur regularly in proteins that do not recognize DNA, so how can the actual DNA binders be correctly identified? One key feature of DNA binding proteins is that the interacting surface tends to be the most positively charged parts of the protein surface. The introduction of electrostatic parameters can greatly improve the ability to distinguish binders from nonbinders. The HTH query server (Ferrer-Costa et al., 2005) uses electrostatic calculations to distinguish true positive from false positive matches to its database of DNA binding structural templates.

Instead of calculating the electrostatics as an addition to structural matches, the eF-Site database (Kinoshita and Nakamura, 2004) is a searchable database of electrostatic surfaces extracted from the PDB. By taking this approach, the server is not limited to DNA binding proteins and includes ligand binding, active sites, and protein-protein interaction surfaces. Another more statistical method (Tsuchiya, Kinoshita, and Nakamura, 2004) uses the shape and electrostatic potential of the surface of the protein and DNA to construct an evaluation function to predict DNA interaction sites. One of the major differences in this approach is that it uses a combination of local and global curvature to describe the protein surface at DNA binding sites.

The use of statistical approaches in the prediction of DNA binding proteins is more commonly seen in sequence-based approaches to the problem, such as the use of position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs; Ahmad and Sarai, 2005). Information on any given residue and its sequence neighbor can be used to predict the likelihood of DNA binding and can be applied even when no sequence homology to known DNA binding proteins is observed. Through the use of a neural network-based algorithm, evolutionary information from amino acid sequences in terms of their PSSMs can be used to make better predictions of DNA binding sites (the method is available at http://www.netasa.org/dbs-pssm/).

A new method developed by Szilagyi and Skolnick (Szilagyi and Skolnick, 2006) combines sequence features and structural parameters to predict DNA binding proteins. By using information such as the relative proportions of particular amino acids in the protein sequence, the spatial distribution of other amino acids, and structural information such as the dipole moment of the molecule, a formula is constructed and DNA binding predictions are based on whether or not the composite score is above a certain threshold. The advantages of the method are its robustness when using low-resolution protein models and its ability to predict DNA binding proteins in their unbound state.

Other Methods

Two important resources provided by the MSD group at the European Bioinformatics Institute are MSDsite (Golovin et al., 2005) and MSDmotif. Both are database-centric approaches but look at different aspects of active sites. MSDsite is a search and retrieval system focused on the bound ligands and active sites of protein structures in the PDB, whereas MSDmotif concentrates on small 3D-structure motifs such as Beta-turns, Asx-motifs, and Nests (Watson and Milner-White, 2002). These motifs are seen to characterize active sites, have structural roles in protein folding and protein stability, and even play roles in enzyme mechanisms. Both databases can be used to identify local similarities that can point to functional or distant evolutionary relationships.

A novel method, THEMATICS (http://pfweb.chem.neu.edu/thematics/submit.html), uses theoretical microscopic titration curves to identify active-site residues (Ondrechen, Clifton, and Ringe, 2001). Titration curves of the most ionizable residues in a protein would be expected to go from protonated to unprotonated forms within a relatively narrow pH range. Analysis of the theoretical titrations shows a small fraction of the curves possess perturbations in the curve where the residue is partially protonated over a wide pH range. Further analysis revels that the residues showing these unusual properties tend to occur in the active site.

Combining Methods

No one method will work in all cases, and each method may suggest a number of different functions with equal probability, so a more sensitive and sensible approach is to use as many different methods as possible. When multiple methods agree on a putative function, it lends greater likelihood to the prediction. This has led to the development of various servers that integrate various sequence- and structure-based methods.

The ProFunc server (Laskowski, Watson, and Thornton, 2005a), developed in collaboration with the Midwest Center for Structural Genomics (MCSC), combines analyses from a wide variety of sources some of which are accessed through SOAP-based web services. The analyses offered range from sequence searches (such as BLAST searches against UniProt or the PDB, and motif matching against Pfam and InterPro), through genome neighborhood and gene location analysis, to wholly structure-based methods. The structure-based approaches fall into almost all of the aforementioned categories and include fold matching (SSM and DALI), surface cleft analysis (SURFNET) and mapping of conservation onto surface, structural motifs (HTH motif and “nest” identification), down to the highly specific three-dimensional template approaches. These last template approaches utilize known catalytic site templates, automatically generated ligand and DNA binding templates, and a novel “reverse template” approach (Laskowski, Watson, and Thornton, 2005b). A recent analysis (Watson et al., 2007) of the server’s ability to predict protein function from structure suggested that the reverse template and fold-matching methods are particularly successful and identify local similarities that are difficult to spot using current sequence-based methods. A method based on the gene ontology schema using GO-slims is also presented that can allow the automatic assessment of hits.

The use of GO terms is also a feature of other integrative approaches. The ProKnow server (Pal and Eisenberg, 2005), like ProFunc, combines information from a combination of sequence and structural approaches including fold similarity (DALI), templates (RIGOR), and functional links taken from the DIP database (Xenarios et al., 2000) of protein interactions. The most important difference is that ProKnow uses Bayes’ theorem to weight the significance of all results, presenting an overall function to the user in terms of GO annotation. Another approach, PHUNCTIONER, automatically extracts the sequence signal responsible for protein function through structural alignments and 3D profiles of conserved residues (Pazos and Sternberg, 2004). The GO database is once again used but this time to provide the functional features used to train the method. Using the method, 3D profiles were constructed for over 120 GO annotations that can be used for function prediction. The matching of a new protein to one of these profiles is a strong indicator of matching the associated GO annotation and hence from this function may be inferred.

The Query3D (Ausiello, Via, and Helmer-Citterich, 2005a) method and associated database, PDBfun (Ausiello et al., 2005), takes a residue-centric approach when integrating information from multiple sources. These range from protein cavity location and solvent accessibility, through ligand binding ability, secondary structure type to residue, sequence, and domain-level properties. The software also acts as a database management system and allows complex queries to be constructed based on residue function and can compare subsets of residues. This allows residues sharing certain properties in all proteins of known structure to be identified at the same time as finding the query protein’s structural neighbors in the PDB.

STRUCTURAL GENOMICS: HIGH-THROUGHPUT FUNCTION PREDICTION

Large-scale genome-sequencing projects led to the birth of structural genomics (Blundell and Mizuguchi, 2000), a large-scale project aimed at experimentally determining a large number of protein 3D structures as rapidly and accurately as possible using high-throughput methods. The initial trial projects have completed and the full-scale production of protein structures has now started along with investment in new technologies to address the more challenging problems of complexes and membrane proteins (Service, 2005). As a consequence, the numbers of structures deposited in the PDB with little or no functional information has steadily increased.

An early review of 15 hypothetical proteins of known structure and their functional assignment (Teichmann, Murzin, and Chothia, 2001) provided some glimpses of the quality of functional assignments that can be made from structure. The structure and sequences of homologues of known function were used to find surface cavities and grooves in which conserved residues indicated an active site. This, along with bound cofactors in the structure, in combination with experimental work, was assessed according to the depth of functional information that could be obtained. For the 15 proteins, detailed functional information was obtained for a quarter of them. For another half, some functional information was obtained, and for another quarter, no functional information could be obtained.

A more recent study (Watson et al., 2007) assessing function prediction from structure looked at 92 proteins of known function from the MCSC. The results were backdated to the release date of each query to see how the ProFunc server would have performed at the time. In approximately 55% of cases, the top fold match was able to provide the correct functional assignment. The standard template methods were shown to provide some success but the most accurate structure-based method was identified as the reverse template approach, providing the correct function in 60% of the cases.

Specific Examples of Functional Assignment from Structure

BioH: A New Carboxylesterase. BioH was known to be involved in biotin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli but had no identified biochemical function. The three-dimensional structure of BioH was determined by the MCSC to 1.7 Å (Figure 21.4a) (Sanishvili et al., 2003). Analysis of the structure using 189 manually curated residue-based templates from a variety of known enzyme-active sites identified a putative catalytic triad similar to that of hydrolases. The best matching template was derived from PDB entry 1tah (triacylglycerol lipase from Psuedomonas glumae) and the structural match is illustrated in Figure 21.4a. The prediction was tested experimentally using apanel of hydrolase assays and the function was confirmed as a carboxylesterase with a preference for short acyl chain substrates.

Mj0577: Putative ATP Molecular Switch. Mj0577 is an open reading frame (ORF) of previously unknown function from Methanococcus jannaschii. Its structure was determined at 1.7 Å (Figure 21.4b) (Zarembinski et al., 1998). The structure was found to contain a bound ATP molecule, picked up from the E. coli host. The presence of bound ATP led to the proposition that Mj0577 is either an ATPase or an ATP binding molecular switch. This is an example where a ligand-based approach is used to predict the function of a protein in a manner related to the surface cleft strategies described earlier. Further experimental work showed that Mj0577 cannot hydrolyze ATP by itself and can only do so in the presence of M. jannaschii crude cell extract. Therefore, it is more likely to act as a molecular switch, in a process analogous to ras-GTP hydrolysis in the presence of GTPase activating protein.

Figure 21.4. Prediction of function in earnest: three structures solved in the absence of functional information. (a) BioH: a new carboxylesterase. The BioH structure showed a significant match to a known active site template from PDBentry 1tah (Pseudomonas glumae lipase). The structures are shown side by side with the equivalent residues shown in green sticks. The template residues from 1tah (Ser 87, His 285, and Asp 263) and the matched residues from BioH (Ser 87, His 235, and Asp 207) are shown superposed as thick and thin sticks, respectively, in the box below. (b) Putative archaeal ATPase molecular switch. The bound ATP molecule, key to the unlocking of this protein’s function, is shown in a ball-and-stick form. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

We have seen in this chapter that structure-function relationships are key to understand in molecular terms how a protein works. Structural data can complement experimental work; for example, if it is known from biochemical experiments that a particular protein of interest binds ATP, the structure of the protein complexed with an analogue of ATP will reveal exactly where ATP binds. It will also identify the residues on the protein that might stabilize the interaction between ligand and protein, and the potential structural consequences of ligand binding.

Structural data can also guide experimental work in eliciting the function of a protein. For example, if one can infer from structural homology that a particular protein is a hydrolase with a nucleotide binding domain, one can carry out experiments to confirm this and even identify possible substrates.

As structural genomics projects progress, determining protein function from structure with no prior knowledge of the function will become increasingly important. As described, a great number of methods exist to do this, and several servers have been developed to integrate the information from multiple sources in an attempt to improve predictions. However, there are still many proteins for which no functional information can be inferred from any existing method and therefore there is still a need to develop new methods to address these problematic structures. To date the methods that work best rely on the recognition of different homologues—identified either by whole fold matching or by local template matching.

When automatically assigning function to proteins, great care must be taken annotating those that are distantly related, so as to maintain accuracy in the databases. This is made more difficult by the fact that functions can differ in proteins that are almost identical and the converse is also true with examples of similar function in very different proteins. Ultimately, however, function will need to be assessed experimentally and this is a time-consuming process. In order to address this potential bottleneck, several high-throughput approaches to enzyme function assays and ligand binding assays have been developed to allow mass screening for specific functions.