22

STRUCTURAL ANNOTATION OF GENOMES

INTRODUCTION

Physical techniques such as X-ray crystallography and NMR allow the determination of individual protein structures on the atomic level. Such information is invaluable for detailed studies of protein function. However, directly determining the structure of proteins by physical methods is laborious and expensive. Although there are structures for ~8000 different proteins in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/) as of June 2007, there are currently ~5 million protein sequences in UniProt (http://www.ebi.uniprot.org) and the number of sequences grows at a faster rate than that of solved structures.

Therefore, time and cost constraints make it impossible to directly determine the structures of proteins in all genomes with current technology. Fortunately however, homology modeling allows reasonably accurate prediction of structure for sequences with >40% sequence identity over their whole length (Marti-Renom et al., 2000). In addition, fold recognition techniques allow structures to be predicted at much lower levels of sequence similarity and this can often give helpful insights into protein functions. Consequently, only a sampling of structures needs to be solved, although it is not simple to determine how this should be done (see Section ’’Can We Determine All the Structures Present in the Genomes?—Structural Annotation of Genomes and Structural Genomics’’). Structural genome annotation can help determine which genome sequences we can already describe structurally and which we need to target for structure determination.

Another reason why structural annotation of genomes is so useful is that structures are much more conserved than sequence during evolution, annotation allows us to merge sequence-based families into larger superfamilies of homologues that could not have been identified using purely sequence data. Structural data can be exploited through classifications such as those of CATH and SCOP (see Chapters 17 and 18), which classify domains into homologous superfamilies based on their structural similarity. Reading Chapters 17 and 18 is highly recommended to fully appreciate and understand concepts presented in this chapter.

Using sensitive homology recognition methods, it is then possible to model these large, structural superfamilies and thereby determine distant homologous relationships between genomic sequences without knowledge of their structure. These approaches have sometimes allowed insights into protein evolution and function that would not have been possible with sequence data alone (see Section ’’What can Structural Genome Annotation Tell Us About Evolution?’’).

In this chapter we discuss the following:

- The availability of completed genomes (Section ’’Availability of Completed Genomes’’).

- The most commonly used structure-based methodologies for annotating genomes (Section ’’Methodologies for Identifying Structural Protein Domains in Genomes’’).

- How much of the genomes can be accounted for with these data (Section ’’How Well are Genomes Covered by Structural Domain Annotation?’’).

- How structural genomics (SG) is seeking to increase structural coverage of the genomes (Section ’’Can We Determine All the Structures Present in the Genomes?— Structural Annotation of Genomes and Structural Genomics’’).

- What these structural annotations can tell us about evolution (Section ’’What can Structural Genome Annotation Tell Us About Evolution?’’).

- What resources are available for acquiring the relevant data (Section ’’Structural Genome Annotation Resources’’).

AVAILABILITY OF COMPLETED GENOMES

Integr8, hosted at the European Bioinformatics Institute, provides access to proteomes from all completely sequenced organisms derived from UniProt and other resources. Similar data are available from elsewhere such as NCBI. According to the NCBI genomes resource (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genomes/), as of June 2007, there are currently 27 eukaryotic, 483 bacterial, and 41 archaeal complete genomes. Those in progress, largely microbial but many eukaryotic as well, total over a thousand more genomes to be completed. Currently, completed genomes contain an estimated 800,000 open reading frames.

METHODOLOGIES FOR IDENTIFYING STRUCTURAL PROTEIN DOMAINS IN GENOMES

A simple protocol for identifying protein structures in genomes might be to take the sequences of known structures from the Protein Data Bank and BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) them against the genomes. In what ways can this be improved upon?

First, BLAST is not the most sensitive method of homology detection; there are also profile methods such as PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) (Eddy, 1996; Karplus, Barrett, and Hughey, 1998) that additionally use evolutionary information to detect more distant homologues and allow greater coverage of the genomes than could otherwise be achieved with BLAST (Park et al., 1998). Even more sensitive than profile methods is using an approach that threads sequences through known structural folds to find the most optimal structure (Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1992). Rather than asking whether sequences have a common ancestor, threading attempts to determine whether a sequence is likely to adopt a particular structure and therefore is a member of a known fold group. However, as profile methods are slower than BLAST, threading is even more time demanding. Consequently, most structural annotation is performed using profile methods, which are both sensitive and reasonably fast. The implementation of profile-based methods is discussed in Sections 2.2 and 2.3.

The second major improvement gained from using structures for genome annotation results from using structural classifications that define groups of structurally similar domains. These domains may have very little sequence similarities but share structural similarities and are therefore classified together. From these classifications, it is easier to group very diverse representatives of a superfamily, as defined by CATH, and generate an optimum set of representative profiles to further detect other homologues.

Classifying Structural Domains

Structural protein domains are often described as compact, independently folding units within a protein chain (Richardson, 1981). By analyzing and comparing the structures and sequences of the different independent units, it is possible to group them into sets of homologous structures (superfamilies) and those with a similar secondary structure composition (architecture) and overall topology (fold). By using diverse examples of domains from each superfamily, a set of sequence profiles that represents each superfamily can then be generated. Since structural similarities are typically easier to recognize than amino acid sequence similarity, this enables the detection of more distant homologies than simply through sequence-based grouping, as exemplified by Pfam.

The CATH (Greene et al., 2007) and SCOP (Andreeva et al., 2004) resources both use a similar hierarchy and approach and are discussed in Chapters 18 and 17, respectively. The initial boundaries and relationships defined by these classifications are determined with a suite of sequence and structure comparison tools and then reviewed by an expert curator, before being placed within the classification. FSSP (Holm and Sander, 1994) is another useful resource that provides a similarity measure (Z-score) between known protein structures, rather than classifying them in an explicit hierarchy.

Using Homology Detection to Predict Structural Domains

Given the sequences from a particular superfamily, the essential steps in identifying structural domains in genomes, or for that matter any other kind of protein domain, are sequence profiling, detection, and resolution. First, it is necessary to determine which features of the sequences are important in defining the superfamily (profiling). Second, these sequence profiles or models must be used to find potential examples of the superfamily in genomes (detection). Finally, it is necessary to determine which are real domains, compared to false positive hits, and resolve any overlapping domains (resolution).

The most common approach is to use remote homology detection methods for the profiling and detection steps. Chief among these methods are HMMs (Krogh et al., 1994; Eddy, 1996).

The structural genome annotation resources, such as Gene3D (Yeats et al., 2006) based on CATH and SUPERFAMILY (Wilson et al., 2007) based on SCOP, use HMMs to profile families and assign domain superfamilies to genomes. Purely sequence-based domains such as Pfam domains are modeled using similar protocols to the structure-based resources (Finn et al., 2006). The 3D-GENOMICS resource (Fleming et al., 2004) uses PSI-BLAST and HMMer to assign SCOP superfamilies, with PSI-BLAST optimized for genome annotation (Muller, MacCallum, and Sternberg, 1999). The Genomic Threading Database(GTD) (McGuffin et al., 2004) uses PSI-BLAST and a threading-related method to validate matches (discussed in Section 3.3). Gene3D will be used as the main example in this chapter for the discussion of structure-based approaches to genome annotation with differences between the methods highlighted subsequently.

The Gene3D Protocol for Predicting CATH Domains in Proteins of Unknown Structure. Hidden Markov Models are perhaps the most successful approach for modeling protein domain families (Park et al., 1998). For an alignment of a family of homologous protein domain sequences, HMMs capture the distribution of residues at each conserved position as well as the likelihood of deletions and insertions at/or between the conserved positions, respectively. It has been shown that HMMs best model whole superfamilies, while multiple models should be built for subclusters within each superfamily (Gough et al., 2001; Sillitoe et al., 2005). The full diversity of a superfamily cannot be adequately captured in a single model as superfamilies frequently contain sequences with low pair-wise identity that cannot be successfully aligned. Therefore, multiple models are generally used—one for each subfamily within a superfamily. However, full profiles capture more remote homologues than within the subfamiliy, so models for each subcluster may therefore overlap, but not completely.

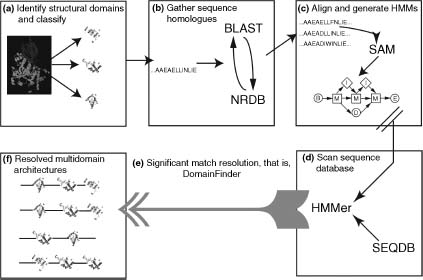

In CATH, sequences within homologous superfamilies are clustered at 35% identity and the resulting sequence families are ideal for building alignments and training HMMs (Reid, Yeats, and Orengo, 2007). As shown in Figure 22.1, the representative sequences from each cluster are chosen as the seeds from which to build HMMs. The representative for each cluster is the cluster member with the highest resolution structure and has the sequence length closest to average for the cluster. In Gene3D, the target2k program, distributed as part of the SAM HMM package (Karplus, Barrett, and Hughey, 1998), is used to generate the alignments based on these representatives. Target2k uses an iterative HMM procedure to build an alignment from, in this case, the GenBank nonredundant protein database. These alignments provide an enrichment of additional sequence data not present in the structural databases.

The sequence alignments produced by target2k are converted into HMMs using the w0.5 program from the SAM package. Gene3D uses HMMer rather than SAM to find domains; therefore, the SAM models are converted into HMMer models. Wistrand and Sonnhammer (2005) showed that SAM has superior model building performance, while HMMer scores are deemed more accurate than SAM. In addition, HMMer scores HMMs against sequences much faster than SAM.

Each CATH domain superfamily is therefore modeled by one or more HMMs. It is then necessary to use these models to determine where domains occur in the genomes. Each HMM (7794 in CATH v3.1 from 2091 superfamilies) is scanned against all the sequences from UniProt and RefSeq, including all completely sequenced genomes. In some cases, there are overlapping domains and these need to be resolved to produce coherent multidomain architectures (MDAs). The program DomainFinder performs this task (Lee et al., 2005). DomainFinder works by iteratively assigning the most high scoring, nonoverlapping domain to each protein, up to an E-value of 0.01. Allowing overlapping domains increases the sensitivity and specificity, but reduces the certainty over domain boundaries.

Figure 22.1. Workflow for creating CATH multidomain architectures in Gene3D. (a) Chains are chopped into domains and classified in CATH. (b) Sequence relatives are gathered using SAM T2K (incorporating BLASTand an iterativeHMMprocedure). (c) Sequence alignments are converted into HMM. (d) Scanned against UniProt and RefSeq. (e,f) DomanFinder is used to resolve domain architectures based on E-value and overlap.

Variations in the SUPERFAMILY Protocol. The SUPERFAMILY procedure for modeling, detecting, and resolving structural domain families predicted for SCOP superfamilies is much the same as for Gene3D (Gough et al., 2001). It differs, however, in using SAM for detection of structural domain families rather than HMMer and in allowing a 20% overlap between adjacent domains.

In the most recent version of SUPERFAMILY, a family-level classification has been introduced (Wilson et al., 2007). In addition to specifying the superfamily of protein domains identified in genomes, the more specific family is also specified if it can be determined. This has been achieved using a hybrid pair-wise-profile method (Gough, 2006). As in the original SUPERFAMILY procedure, a query sequence and other domains from each family within that superfamily are aligned to a particular HMM. From this, an alignment can be inferred between the query domain sequence and the members of each family by aligning those residues that align to the same position in the HMM. An E-value score is calculated based on whether the query sequence scores highly to one family representative relative to the others. A low E-value indicates clear membership to one particular family.

Using Fold Recognition to Predict Structural Domains

The approaches described above recognize homologues by using sequence patterns indicative of a common evolutionary ancestor. Fold recognition methods such as threading have also been used for structural annotation of genomes and have a similar aim to homology detection. Threading does not primarily exploit evolutionary information to recognize structural domains in sequences, instead it determines how well a sequence fits a particular fold (Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1992). Because very different sequences can form similar structures, threading allows very distant homologous domains, and even analogous domains, to be recognized. Full structural threading requires large amounts of computing power and it has been shown that using a more heuristic approach with data derived from threading, as implemented in GenTHREADER (McGuffin and Jones, 2003) and 3D-PSSM (Kelley, MacCallum, and Sternberg, 2000), produces similar results (Cherkasov and Jones, 2004).

The GTD (McGuffin et al., 2004) uses GenTHREADER (McGuffin and Jones, 2003) to annotate genomes with fold level SCOP annotations. GenTHREADER combines threading and homology-based sequence alignment scores generated by PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) with scores based on secondary structure predictions (Marsden, McGuffin, and Jones, 2002). Results from each of these methods are combined using a neural network. The Genomic Threading Database does not however provide resolution of multidomain chains.

Predicting Other Structural Features

Various other structural and functional features of proteins can be predicted when annotating genomes, including coiled-coil regions (involved in protein oligomerization), transmem-brane helices (membrane-spanning regions, which are present in ~50% of drug targets), transport peptides, protein modification sites, and regions of low complexity—representing a significant source of information for functional prediction. These annotations are also useful for determining regions of proteins that may not contain globular domains or are otherwise unsuitable (e.g., containing transmembrane helices) as structural genomics targets for stucture elucidation.

Coiled-coils, protein structures involving intertwined alpha helices, can be predicted by sequence comparison to known coiled-coils and by recognizing heptad repeats of side chain chemistries necessary to form these structures. This is implemented in the program COILS (Lupas, Van Dyke, and Stock, 1991). Transmembrane helices can be predicted by looking for patterns of residue types, principally ~20 residue stretches of hydrophobic residues (Cuthbertson, Doyle, and Sansom, 2005). Transmembrane helix prediction is implemented in several programs of which SPLIT4 (Juretic, Zoranic, and Zucic, 2002), TMHMM2 (Krogh et al., 2001), HMMTOP2 (Tusnady and Simon, 1998), and TMAP (Persson and Argos, 1997) are thought to perform the best. Low-complexity regions can be predicted using SEG (Wootton and Federhen, 1996).

Accuracy of Methods

There has been much discussion in the literature on the accuracy of remote homologue detection and fold recognition methods for single domains (Park et al., 1998; Rychlewski and Fischer, 2005; Reid, Yeats, and Orengo, 2007). For example, Reid, Yeats, and Orengo (2007) showed that profile methods perform very well at annotating remote homologues (<35% identical); PSI-BLAST, HMMer, and SAM all achieve at least 80% sensitivity with less than 1% errors. There has however been little work published on the accuracy of methods in resolving multidomain architectures. Resources such as SUPERFAMILY provide confidence values for individual domain assignments (E-values), but not for the multidomain architecture as a whole. One exception is work of Muller, MacCallum, and Sternberg (1999) in which genome annotation using PSI-BLAST with SCOP domains was benchmarked. In a benchmark set of 1254 sequences with 1621 domains, 652 domains (~40%) were correctly assigned with 16 false positives at E-value of 5 x 10–4.

There is a need for further work in this area resolving structure-based genome annotation. The problem of how to resolve a multidomain architecture from multiple hits is not a simple one and reliable benchmarks would be of great use to the structural annotation community.

HOW WELL ARE GENOMES COVERED BY STRUCTURAL DOMAIN ANNOTATION?

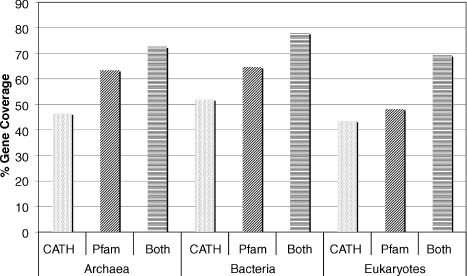

Using the methods outlined above, how much of known genomes can be annotated? Using the current version of Gene3D (v6), it can be seen that coverage between the three superkingdoms is not even (Figure 22.2). This reflects biases in structures deposited in the PDB and also the different distributions of folds in the different superkingdoms. In archaea, 46 ± 8% of the genes in each genome have structural annotation, 52 ± 7% for bacteria and 44 ± 10% for eukaryotes. Figure 22.2 also shows that Pfam (sequence-based) domains have higher coverage than CATH (structure-based) domains due to the limited number of known structures. The combined coverage created by assigning CATH domains and nonoverlapping Pfam domains shows that CATH domains can be assigned to regions that are not covered by the sequence-based domains. This is because structural domain classifications allow more distantly related domains to be recognized. The two approaches are therefore complementary.

Figure 22.2. Percentage of genomes covered by CATH domains and Pfam domains, and using both together for the three superkingdoms. Created using complete genomes from Gene3D v6.

CAN WE DETERMINE ALL THE STRUCTURES PRESENT IN THE GENOMES?—STRUCTURAL ANNOTATION OF GENOMES AND STRUCTURAL GENOMICS

Looking at the structural annotation of genomes, we see that although there are a limited number of experimentally determined structures, many proteins without solved structures are likely to adopt known folds. Those remaining unannotated fall into two classes: those that have a known fold but the sequence has diverged too far to be detected and those that have novel folds. Structural genomics initiatives (e.g., http://www.nigms.nih. gov/Initiatives/PSI/) aim to solve structures for unannotated sequences as efficiently as possible. Novel structures are predicted and put forward for experimental characterization, and bioinformatic methods are used to identify these remote homologues.

The precise aims of SG initiatives vary (Todd et al., 2005; Chandonia and Brenner, 2006), but all of them are working toward solving protein structures to fill the annotation gap. Ideally, the result would be a sufficient sampling of all protein structures such that those remaining unsolved could be successfully modeled using the solved structures as templates. Currently, reliable structural models can be achieved using a template of >30% sequence identity with >60% overlap; however, resolving important functional features often requires >60% sequence identity. Thus, some SG initiatives aim to solve new folds where there are no relatives of known structure, while others aim to increase the knowledge of structural and functional diversity in existing folds/superfamilies.

Using annotation resources, such as Gene3D and SUPERFAMILY, unannotated regions can be identified and targeted by structural genomics initiatives. These may be Pfam families that are not related to CATH or SCOP superfamilies, or families created by clustering the sequences of structurally unannotated regions in the genomes (e.g., NewFams) (Marsden et al., 2006). Solving the larger families/clusters identified in the unannotated regions will result in a greater increase in structural genome coverage. Unfortunately, determining these potentially novel proteins is not as simple as finding unannotated regions.

Having accounted for known structural (e.g., CATH) domains, it is necessary to exclude domains that are less useful or unlikely to be amenable to structure determination. There are many factors that should be taken into account, but two that are most important involve singletons and proteins intractable to crystallization. Singleton domains are unannotated domain-like regions (>50 residues) that have no homologues as determined by sequence-based methods. These domains are likely to be novel but not useful for modeling other domains. These species-specific domains are thought to make up between 7% and 22% of domains in genomes (Marsden, Lewis, and Orengo, 2007).

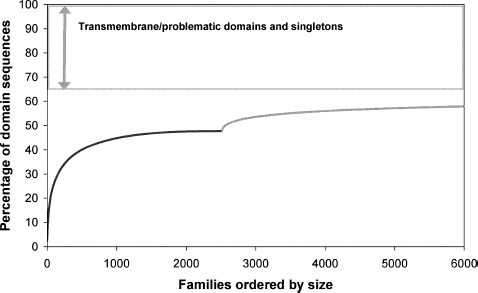

Regions of proteins that will be intractable to high-throughput structural characterization also need to be excluded. Typically, between 13% and 18% of proteins in a genome are thought to contain problematic regions such as transmembrane sequences, coiled-coils, or low-complexity regions (Marsden, Lewis, and Orengo, 2007). These regions cannot easily be solved with current techniques; transmembrane sequences are very hydrophobic and low-complexity regions tend to be unstructured. Disordered regions of proteins (those without a unique structure) are increasingly seen as important for protein function but are intractable to traditional methods of structure determination. In some structurally solved proteins, disordered regions are thought to make up between 5% and 30% of their entire length (Linding et al., 2003) while others may be entirely disordered (Uversky, 2002). Figure 22.3 (Marsden, Lewis, and Orengo, 2007) shows that we currently achieve less than 50% structural coverage of known domain families in UniProt. Solving structurally uncharacterized Pfam-A and completely uncharacterized NewFam (Marsden et al., 2006) families will increase this coverage by ~10% and that 35% of domain sequences are not tractable to structural genomics.

Figure 22.3. Structural coverage of domain sequences in Swiss-Prot-TrEMBL families, ranked in order of number of members in family, largest to smallest. The black line represents coverage of domain sequences by 2486 CATH and Pfam-A structural families, whereas the gray line represents additional coverage that would be achieved by solving a structure for structurally uncharacterized Pfam-A and NewFam domain families (Marsden, Lewis, and Orengo, 2007).

Although bioinformatic methods can identify families of proteins that are more likely to have novel structures, there are limitations in this approach. Currently, only 10% of targets solved by structural genomics initiatives have novel structures (Bourne et al., 2004) that can be explained by several factors. First, not all initiatives aim to solve novel structures but target functionally distinct members of known folds. Second, homology detection and fold recognition methods are not perfect. Third and perhaps most important, known experimental conditions for structure determination may favor known structures and their homologues. The effect of the experimental condition can be observed in the targeted structures analyzed by Bourne et al. (2004) showing half of this set of proteins are homologous to a subset of structures, presumably repeatedly selected by experimental conditions, compared to 90% of the solved structures.

WHAT CAN STRUCTURAL GENOME ANNOTATION TELL US ABOUT EVOLUTION?

The Distribution of Structural Domain Families in the Genomes Follows a Power Law

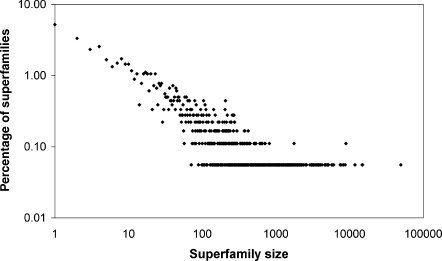

Several groups have shown that protein domain families are not evenly distributed within genomes (Huynen and van Nimwegen, 1998; Apic, Gough, and Teichmann, 2001 Qian, Luscombe, and Gerstein, 2001). As shown in Figure 22.5, the distribution of protein domain superfamilies follows a power law, indicating that relatively few families account for a large proportion of domains and most families are very small. This uneven distribution is even more apparent when the domains are grouped according to folds. The most common folds are so frequent that they have been termed “superfolds” (Orengo, Jones, and Thornton, 1994). Structures in these fold groups tend to carry out a wide range of functions and are believed to maintain favorable residue packing while accommodating extensive residue substitution (Shakhnovich et al., 2003).

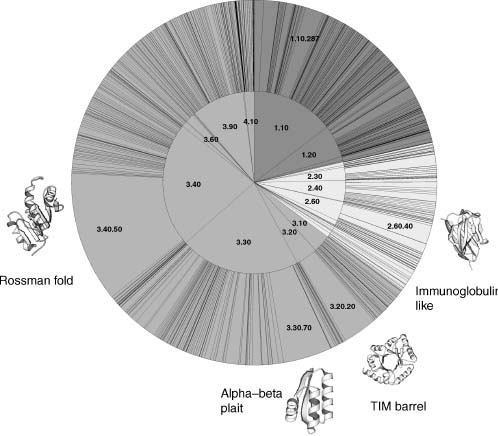

Figure 22.4. The distribution of CATH domains in 535 completed genomes in Gene3D. CATH classes are illustrated by color: purple for mainly alpha structures; yellow for mainly beta structures; green for alpha–beta structures. The inner wheel shows different architectures and the outer wheel different folds. For the most numerous folds, example domains are shown on the outside of the wheel. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

The Rossman fold, for instance, makes up a large proportion of known structural domains in completed genomes. Figure 22.4 shows a CATH wheel with the distribution of known architectures and folds in completed genomes, derived from Gene3D. It shows a distinct bias toward certain architectures (e.g., 1.10—orthogonal bundle, 3.30—two-layer sandwich, and 3.40—three-layer sandwich) and certain folds (e.g., 2.60.40—immunoglobulin-like, 3.30.70— αβ plait, 3.20.20—TIM barrel, and 3.40.50—Rossman fold). Within individual genomes, there is the same bias toward the superfolds; however, the smallest families are specific to certain species or subkingdoms. This is the tail of the power law distribution, where . we find many families with very few instances (Figure 22.5). This fact has rather negative consequences for structural genomics as discussed above.

Figure 22.5. Power-law distribution of protein domain families in Gene3D (v6). Superfamily size is the number of members in the superfamily

Using Protein Structural Domain Annotations to Explore the Evolution of Diverse Multidomain Protein Architectures in Nature

Most proteins contain multiple domains—perhaps greater than 90% in eukaryotes, somewhat lower in prokaryotes (Apic, Gough, and Teichmann, 2001). It has been known for some time that new functions can be achieved by mixing and matching existing domains— domains are thought to be the fundamental functional units of proteins (Edelman and Gall, 1969). Various aspects of such combinations of domains or multidomain architectures have been studied, revealing the nature of evolution at the multidomain level.

There are far fewer domain combinations/protein architectures observed in Nature than are possible. Around 5000 CATH and Pfam families can be mapped to the genomes. There are then >107 possible two-domain proteins and >1011 possible three-domain proteins. However, we observe only 50,000 protein families (i.e., distinct multidomain protein families) using Gene3D (Marsden et al., 2006), and indeed Chothia et al. (2003) estimated that less than 0.5% of possible combinations are observed. Most domains then are seen in very few multidomain contexts, whereas more frequently occurring domains are seen in partnership with many different domain families (Apic, Gough, and Teichmann, 2001; Lee et al., 2005). These highly recurring domains are mostly performing important generic functions such as providing energy or redox equivalents for reactions or binding DNA (Apic, Gough, and Teichmann, 2001). This suggests that certain domain families are very large because they perform functions that are required in many different contexts (Vogel et al., 2004a) rather than simply because they are energetically favored folds.

Another feature of domain combinations is that some pairs of domain families are highly overrepresented in proteins. These domain pairs have been called supradomains (Vogel et al., 2004b). The 200 supradomains discovered by Vogel and coworkers using SUPERFAMILY were found in 75,000 genome sequences. These are thought to occur because a functional site is created between the domains or simply because it is functionally beneficial to have both types of domains together.

Ancient Domains and LUCA

Structural protein domain classifications bring together more distantly related domains than sequence-based ones and therefore are ideal for identifying ancient domain families (those common to all kingdoms) that were present in the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). LUCA is a hypothetical organism that gave rise to all modern-day species. By determining which domain families were present in LUCA, we can infer how complex it was and which processes went on its cells. Using only sequence data, the most common domain families to all kingdoms are involved in protein biosynthesis (Koonin, 2003). However, when using structural data to bring together more remotely related domains, a more interesting picture emerges (Ranea et al., 2006).

Using restrictive criteria, Ranea et al. (2006) found 140 ancestral domain families common to almost all completely sequenced members of the three kingdoms of life. The domain families thus discovered are known to be involved in all the essential functional systems present in extant organisms, supporting the theory that life prior to the divergence of the three kingdoms was composed of cells in much the same way as it is today (Doolittle, 2000).

Winstanley, Abeln, and Deane (2005) used occurrence of SCOP domains via SUPER-FAMILY to determine the relative age of protein folds. Using a species tree and the presence or absence of a particular fold in each organism with a completed genome, the position at which each fold first emerged was mapped onto the evolutionary tree. This approach estimated where new folds occurred relative to the appearance of different groups of species. It was noted that folds from the alpha/beta class tend to be far older than those of other architectures.

Several groups have studied the usefulness of structural domain content in constructing phylogenies and refining tree structures representing the evolutionary relationships between species (Lin and Gerstein, 2000;Yang, Doolittle, and Bourne, 2005). Yang, Doolittle, and Bourne (2005) used SUPERFAMILY annotation to determine whether the presence or absence of SCOP superfamilies in 174 complete genomes gave rise to a phylogeny consistent with more sophisticated methods. They found a good correspondence in separating the major clades and achieved greater accuracy with fewer genomes over earlier attempts suggesting that this approach to phylogeny will improve further in the future.

Organismal Complexity and the Evolution of Protein Domain Superfamilies

Several studies have probed into the concept of organismal complexity using structural genome annotation (Vogel, Teichmann, and Chothia, 2003; Ranea et al., 2004; Ranea et al., 2005). Vogel, Teichmann, and Chothia (2003) identified two types of expansions of protein family repertoires by comparing the relative sizes of SCOP domain superfamilies in worm and fly. They termed these progressive and conservative expansions. Conservative expansion increases the ability of an organism to adapt to its environment, whereas progressive expansion leads to significant changes with possible selective advantages, but not necessarily the case. Conservative expansion was seen in two chemoreceptor families in the less complex worm. Progressive expansion was observed in the fly where expanded families tend to be involved in cell-cell communication such as receptors involved in neuronal development. These findings highlight the fact that expansions in different domain families are not equal in terms of their impact on organismal complexity. Instead, some families contribute much more to the development of complex multicellular organisms.

Ranea et al. (2004, 2005) investigated relative expansions in protein structural domain families across 100 completely sequenced bacterial genomes identifying 200 domain families that were common to all species; 27 families exhibited no variation in the number of relatives between genomes; 30 mostly metabolism-related families had expanded linearly with increased genome size; and 27 mostly regulation-related families expanded non-linearly. Hence, increasing metabolic complexity was associated with an increasingly greater cost in terms of regulation, thus allowing limits to be suggested for optimal bacterial genome sizes (Ranea et al., 2004).

Structural Domain Annotation and Phylogenetic Profiling

Phylogenetic profiling, introduced by Pellegrini et al. (1999), allows the identification of coevolving proteins by determining those proteins that are always present or absent together in different species. Coevolving proteins tend to be functionally related and therefore phylogenetic profiles allow for improved functional annotation of proteins.

Pagel, Wong, and Frishman (2004) were the first to use domains rather than whole protein sequences in this context, and more recently Ranea et al. (2007) used CATH structural domains from Gene3D to construct phylogenetic profiles capturing protein coevolution. One of the main problems in using phylogenetic profiles is identifying orthologs, a key factor in the success of phylogenetic profile methods. Ranea et al. (2007) used the subclusterings of domains available in Gene3D to aid the identification of distinct functional subgroups within domain families, narrowing down the identification of orthologs.

Exploiting Structural Annotation of Genomes to Study the Evolution of Metabolic Networks

The two principal models of metabolic network evolution are the retrograde model first proposed by Horowitz (1945) and the patchwork model introduced by Ycas (1974) later expanded by Jensen (1976). The retrograde model proposes that when a metabolite A is scarce in the environment, it is advantageous for an organism to recruit an enzyme that synthesizes A from environmentally available precursors (B, C). If B (or C) becomes scarce, then another enzyme might be recruited to synthesize B (or C) from its precursors. Generally associated with this model is the proposition that each novel enzyme is recruited by duplication from the previous enzyme in the pathway, having similar chemistry but different substrate specificity. Conversely, in the patchwork evolution model, enzymes with broad substrate specificities have duplicated and specialized with paralogs appearing in different pathways. If the retrograde model was correct, we would expect to see clustering of homologues in pathways with the last metabolic enzyme being the most ancestral. The patchwork model instead predicts that homologues would be spread between different pathways. Therefore, the use of effective homologue detection methods on whole sets of enzymes from different genomes is very useful in identifying which evolutionary model is being utilized.

Teichmann et al. (2001a, 2001b) used HMMs built on SCOP superfamilies (before SUPERFAMILY) while others have used PSI-BLAST-assigned SCOP domains (Saqi and Sternberg, 2001; Alves, Chaleil, and Sternberg, 2002) or Gene3D (Rison, Teichmann, and Thornton, 2002) to determine which evolutionary mechanism hypothesis is correct. Homologues were mostly found distributed across pathways supporting the patchwork model of evolution (Teichmann et al., 2001b; Rison, Teichmann, and Thornton, 2002), although some superfamilies were shown to be specialized for particular pathways (Saqi and Sternberg, 2001).

Transcription Factors and Regulatory Networks

Structural domain assignments from the SUPERFAMILY database have also been used to study gene regulatory networks (Teichmann and Babu, 2004). Gene regulatory networks consist of interactions between genes and the transcription factors that regulate their expression. It was shown using SUPERFAMILY that most of these interactions (90%) have arisen by duplication of pre-existing transcription factors or target genes and that half of these duplications led to inheritance of the interaction while the other half gained new interactions.

Kummerfeld and Teichmann (2006) have produced a structurally annotated database of transcription factors using SUPERFAMILY HMMs. Their prediction method involves a curated subset of HMMs that pertain to only those transcription factor superfamilies that are involved in sequence-specific DNA binding. These are the transcription factors that are important for differential expression within organisms.

STRUCTURAL GENOME ANNOTATION RESOURCES

Gene3D Resource for Structural and Functional Annotation of Genomes

Gene3D (Yeats et al., 2006) is a genome annotation resource that provides access to the predicted CATH protein domain architectures and other sequence features (transmembrane helices, coiled-coils, etc.), as well as functional information (e.g., GO (Harris et al., 2004) and KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2006)), protein-protein interaction data (e.g., Intact (Kerrien et al., 2007)), and microarray expression profiles (from ArrayExpress (Parkinson et al., 2007)). All of UniProt and RefSeq sequences are annotated with CATH structural domains, including complete genomes identified by Integr8. Pfam annotation is also included, increasing the number of proteins that can be annotated. To facilitate functional grouping, protein sequences are clustered into hierarchical families using TribeMCL clustering (Enright, Van Dongen, and Ouzounis, 2002). As discussed above, this resource has been successfully used in studying evolution, identifying sequence relatives, and determining structural genomics targets.

Gene3D can be accessed through a Web site (see Table 22.1) that provides access to all the annotation via a single search box, which accepts UniProt, PDB, RefSeq, CATH, and Pfam identifiers. BLAST searches and HMM scans can also be used to retrieve annotation for homologues of proteins or families of interest. Completed genomes can be browsed and the data can be downloaded as flat files for more intensive investigations.

A recent addition to the Gene3D resource is PhyloTuner profiles (Ranea et al., 2007). PhyloTuner makes use of the hierarchically clustered CATH domains in Gene3D to identify coevolving domain families and inferfunctional relationships.

TABLE 22.1. Details of Structural Genome Annotation Resources

SUPERFAMILY (Wilson et al., 2007) provides access to predicted SCOP domains. The data can be accessed using keyword searches for sequence identifiers (e.g., UniProt), PDB identifiers, organism names, SCOP superfamily names and identifiers, and SUPERFAMILY model numbers. Sequences can be submitted for domain assignment and, if not found in the database, are scanned de novo against SUPERFAMILY HMMs. If no significant hits are found, the powerful profile-profile method PRC is used to search for more remote hits. SCOP family-level assignments are presented in addition to the SUPERFAMILY-level assignment. Statistics for each genome, such as domain composition, can be browsed, and simple genome comparisons can be performed. Domain assignments, alignments, and models can be downloaded.

3D GENOMICS

This resource from the Sternberg group at Imperial College (Fleming et al., 2004) provides SCOP and Pfam domains, secondary structure predictions, and sequence features, such as low-complexity regions, coiled-coils, and transmembrane helices, for completed genomes. It also determines homologous features between genomes on the fly using BLAST. Another useful feature is the ability to perform genome comparisons based on statistics of domain features.

Genomics Threading Database (GTD)

The GTD (McGuffin et al., 2004) uses GenTHREADER (McGuffin and Jones, 2003) to obtain fold-level annotation with SCOP domains for completed genomes. GenTHREADER involves a threading-based approach to the structure prediction in combination with PSI-BLAST and secondary structure prediction. GTD allows keyword searches using PDB and SCOP codes, gene ids and description, and also BLAST searches. Useful summary statistics on fold coverage of the genomes are provided.

InterPro

InterPro (Mulder et al., 2007) brings together data from many different domain annotation resources, allowing users to compare their predictions. It includes both Gene3D (CATH) and SUPERFAMILY (SCOP) structural domain predictions as well as Pfam, Prosite, SMART, Panther, PRINTS, ProDom, and TIGR sequence domains/motifs. It produces a consensus report of these resources, where possible, as InterPro domains.

Structural Genome Annotation with DAS and Web Services

The way in which genome annotation resources are accessed is changing. The need for more integrated and flexible data sources has led to the innovations of Web services and Distributed Annotation System (DAS). Web services allow, for example, those queries that one might perform using a Web browser to be performed within code run locally. For example, large queries can be retrieved and integrated into pipelines without installing and running software on local compute farms. EBI Web services, for example, provide structural genome annotation from InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/webservices/). Web services are soon to be released for Gene3D.

DAS allows multiple sources of genome annotation, which are held on different servers around the world, to be drawn together into different applications. The Gene3D DAS server, for example, provides lists of Gene3D feature ids and protein family clusterings for all UniProt entries. SUPERFAMILY, 3D-GENOMICS, GTD, and InterPro also have DAS services. Information on accessing DAS services can be found at the DAS registration server (http://www.dasregistry.org/index.jsp).

SUMMARY

Knowledge of protein structure is useful for two primary reasons. First, it is essential for understanding protein function because the arrangement of secondary structures and the nature of binding site environments determine substrates and interaction partners. Second, structure is generally more conserved than sequence; therefore, more distant evolutionary relationships can be recognized using structure rather than sequence. Structural genome annotation has been used in diverse areas of research, including studies of protein evolution, taxonomy, organismal complexity, and in the development of new methods for predicting protein functions.

Although it would be desirable to have a catalog of all protein structures, it is not feasible to determine all of these structures directly. Structural domain annotation exploits structural protein domain classifications, such as CATH and SCOP, to determine remotely related domains in genomes. In this way, it expands structural coverage of genomes and also defines those regions that are currently not accounted for by known structures.

It is currently unclear how many of the remaining structural gaps will be filled. Novel structures will continue to be solved for some time yet, and methods of remote homology detection continue to improve, uniting seemingly disparate domain families. We also await technical breakthroughs for solving many membrane proteins and are only just beginning to appreciate the importance of disordered proteins (those with little or no regular structure!).