25

PREDICTION OF PROTEIN-NUCLEIC ACID INTERACTIONS

INTRODUCTION

The specific recognition of nucleic acid sequences by nucleic acid binding proteins is of critical importance to the biological function of every living species. As a result, the phenomena responsible for this recognition process have long been of considerable interest to scientists. Beginning with the pioneering work of Seeman, research into sequence-specific DNA recognition focused on the search for a “recognition code”—a collection of simple rules that would pair particular amino acids to specific bases (Seeman, Rosenberg, and Rich, 1976). However, it was soon realized that any recognition code would degenerate (Pabo and Sauer, 1984) and a general “code” may not exist at all (Matthews, 1988; Pabo and Nekludova, 2000) (Chapter 12).

Given that a sequence-based recognition code appears increasingly unlikely, the key to understanding the process of protein-DNA and protein-RNA recognition lies in the structural, physical, and chemical details of the molecular interactions themselves; these structural mechanisms have received renewed attention with the increased availability of high-resolution structures for protein/nucleic acid complexes. Computational studies of these structures have classified their interactions (Luscombe et al., 2000), describing features of their binding sites (Jones et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2001; Luscombe, Laskowski, and Thornton, 2001) and the evolutionary conservation of their interface residues (Luscombe and Thornton, 2002; Mirny and Gelfand, 2002a).

In other areas of research, structural information has been used extensively to create potentials for prediction of protein structures (Sippl, 1990; Samudrala and Moult, 1998; Xu, Xu, and Uberbacher, 1998; Lu and Skolnick, 2001; Zhou and Zhou, 2002; Zhang et al., 2004a; Skolnick, 2006), as well as protein-ligand (DeWitte and Shakhnovich, 1996; Ischchenko and Shakhnovich, 2002; Velec, Gohlke, and Klebe, 2005; Zhang, et al., 2005), and protein-protein interactions (Jiang et al., 2002; Lu, Lu, and Skolnick, 2003; Zhang et al., 2004a; Zhang, et al., 2005). However, until recently, relatively little effort was devoted to the application of this structural knowledge to the development of computational models for the prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Here, we describe progress toward the application of computational models to the prediction and simulation of protein/nucleic acid interactions.

MOTIVATION

It is self-evident that the ability to accurately and reliably predict the sequence specificity of nucleic acid binding proteins from structure would represent a great intellectual achievement, but the practical applications would also be substantial. Of course, the value of any structure-based method depends upon its generality—if a model can only predict the preferred DNA or RNA binding sequences of a known structure, it is interesting but not especially useful (most structurally characterized protein/nucleic acid complexes have well-known binding sites). If a model can also predict the binding sequences of homologous (though structurally uncharacterized) proteins, it has more value; if it can be used to design entirely novel nucleic acid binding proteins (or to otherwise predict the consequences of mutations to a complex), it is certain to find many applications. Nevertheless, even the most obvious applications—the structure-based identification of DNA or RNA binding sites from known structures—can be practically useful, because many of the “known” recognition sequences of nucleic acid binding proteins are neither absolutely defined nor perfectly characterized (Schneider and Stephens, 1990; Matys et al., 2003). Furthermore, through the use of protein homology modeling techniques (Chapter 30), structure-based methods may one day provide crucial insights into the range and flexibility of recognition sequences for proteins with structures and/or nucleic acid binding properties that are not currently well known.

These applications are analogous to the roles of structure-based models in other areas of biology. The prediction of preferred DNA/RNA binding sequences for a protein has parallels to the problem of structure-based drug design or to the prediction of binding sites for protein-protein interactions (Chapter 26). As noted above, the prediction of nucleic acid recognition sequences for homologous protein sequences is an obvious application of protein homology modeling. Finally, the development of novel nucleic acid binding proteins or the redesign of their specificity is a special case of the rational protein design problem (Chapter 39).

POTENTIAL FUNCTIONS FOR PROTEIN-NUCLEIC ACID INTERACTIONS

Physical Potential Functions

Extending from techniques used to computationally simulate the dynamics of proteins and other molecules (Chapter 37), the same theoretical concepts have been applied to the prediction of energies and specificity for protein/nucleic acid interactions. In particular, the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of nucleic acid molecules and protein-nucleic acid complexes was routinely performed, long before the first efforts to computationally predict the DNA/RNA recognition sequences of proteins from structure (Weiner et al., 1984; Weiner et al., 1986; Cornell et al., 1995; Langley, 1998; Cheatham, Cieplak, and Kollman, 1999; Foloppe and MacKerell, 2000; MacKerell and Banavali, 2000; Wang, Cieplak, and Kollman, 2000; MacKerell, Banavali, and Foloppe, 2001). Thus, MD force fields were among the first potential functions to be applied to the problem of predicting the energetic properties of sequence-specific protein/nucleic acid complexes (Lebrun and Lavery, 1999; Pastor, MacKerell, and Weinstein, 1999; Lebrun, Lavery, and Weinstein, 2001; Marco, Garcia-Nieto, and Gago, 2003; Gorfe, Caflisch, and Jelesarov, 2004; Gutmanas and Billeter, 2004).

Of course, the prediction of nucleic acid binding sequence specificity is a larger problem than simulating the dynamics (or estimating the binding energy) of a given protein/nucleic acid complex. Prediction of DNA or RNA binding sequences requires the ability to accurately estimate the energetic consequence of mutations to the binding interface, which itself requires the ability to simulate (i.e., predict) the structural changes that result from these mutations. Thus, the challenge is closer to the structure-based protein design problem (Chapter 39).

In one of the earliest attempts to apply a molecular dynamics force field to this area of research, Pichierri et al. used the AMBER package to calculate free energy, enthalpy, and entropy “maps” of base-amino acid interactions (Pichierri et al., 1999), a study followed by similar efforts from other groups (Sayano et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2002). By sampling protein side-chain conformations at grid points surrounding canonical nucleotide structures, these efforts were able to identify energetically favorable conformations for particular amino acid/base pair interactions. Somewhat later, Thayer and Beveridge applied their group’s ongoing MD simulation research into sequence-dependent DNA deformation to the prediction of binding sites for the catabolite activator protein (CAP) (Thayer and Beveridge, 2002). They demonstrated a hybrid approach, wherein a hidden Markov model (HMM) was trained using both binding sequence data and nucleotide roll/tilt data obtained from MD simulation of DNA molecules, and found that the use of structural information improved the quality of binding site predictions. Thus, both direct and indirect recognition mechanisms have been explored using MD potentials.

Ultimately, however, molecular dynamics simulations are not well suited to the prediction of cognate binding sequences for nucleic acid binding proteins on a large scale. There is no formal MD analogue to the process of mutation, and the effect of DNA/RNA sequence changes must be approximated through time-consuming simulations of the bound and unbound forms of the different nucleic acid sequences (i.e., simulation of the thermodynamic cycle for every possible combination of nucleotide mutation), and this process is computationally prohibitive for all but the smallest protein-nucleic acid complexes.

For this reason, many applications of physics-based potentials to the problem of binding site prediction have used molecular mechanics techniques, wherein the intent is not to follow conformational changes over time but to directly estimate the free energies of interaction between protein and nucleic acid molecules. For example, Paillard and Lavery (2004) used an energy minimization strategy, based on the AMBER force field, to predict the binding free energies and optimal binding sites for a set of 18 DNA binding proteins. In the process, the authors provided insight into how the recognition of DNA sequences by proteins depends variably (i.e., in a complex-dependent manner) on both protein-DNA interactions both the sequence-specific energy of DNA deformation (“indirect” recognition). The CHARMM package has also been successfully used, particularly for MD simulations of the sequence-dependent flexibility of protein-bound DNA (Pastor, MacKerell, and Weinstein, 1999; Foloppe and MacKerell, 2000; MacKerell and Banavali, 2000; MacKerell, Banavali, and Foloppe, 2001; Huang and MacKerell, 2005).

A somewhat different example is the hybrid physical/statistical potential function used by the ROSETTA protein design software package. Havranek et al. have extended the ROSETTA potential function to protein-DNA systems (Havranek, Duarte, and Baker, 2004), while Chen et al. applied the method to the prediction of protein-RNA interactions (Chen et al., 2004). The ROSETTA potential function not only incorporates many terms common to physics-based potentials (e.g., the Lennard-Jones model of the van der Waals force), but also makes use of a unique statistical model of hydrogen bonding geometry that appears to confer greater sensitivity to the method (Kortemme, Morozov, and Baker, 2003). In the application to protein-RNA interactions, the statistical hydrogen bonding potential function was able to significantly outperform a Coulomb electrostatics model in a number of different decoy discrimination experiments (Chen et al., 2004).

Statistical Potential Functions

In contrast to the complexity of physics-inspired potential functions, some of the earliest efforts to predict sequence-specific protein/nucleic acid interactions from structure involved the use of simple, knowledge-based (“statistical”) potentials (Table 25.1). This class of methods makes use of the database of known structures to derive probability-based scores that can be used to predict protein/nucleic acid interaction energies. While there is a great deal of variation between these methods, all share a common theme: the database of known protein-nucleic acid structures is assumed to adequately represent the distributions of particular “features” that can be observed in any real biological structure. Examples of such “features” include interatomic distances, torsion angles, bond lengths, and (in the case of protein/nucleic acid interactions) the spatial distributions of protein atoms and residues around the nucleotide bases.

TABLE 25.1. Classification of Methods for Modeling Protein/Nucleic Acid Interactions

| Class | Description | Examples |

| Physical | Potential functions derived from physical (or physics-inspired) models of atomic interaction (e.g., Lennard–Jones, Coulomb Electrostatics, Born Solvation, etc.) | Cornell et al. (1995), Pichierri et al. (1999), MacKerell, Banavali, and Foloppe (2001), Endres et al. (2004), Paillard and Lavery (2004) |

| Statistical | Potential functions derived from statistical formalisms (e.g., Bayes’ Networks, Hidden Markov Models, Support Vector Machines, etc.), and parameterized using data from known protein/nucleic acid structures. | Kono and Sarai (1999), Liu et al. (2005), Zhang et al. (2005), Robertson and Varani (2007), Donald et al. (2007) |

| Hybrid | Methods that incorporate both physical and statistical components. | Thayer and Beveridge (2002), Chen et al. (2004), Havranek et al. (2004), Morozov et al. (2005) |

From a biophysical perspective, knowledge-based potential functions are rooted in the assumption that individual atomic structures represent low-energy molecular conformations, reflecting the optimal contributions of many different microscopic forces. If this assumption holds true, then a sufficiently large database of randomly sampled structures would capture the physically realistic range of any particular structural feature. Moreover, these features would be expected to occur in proportion to their energies, with high-energy features observed far less frequently than low-energy features. A full discussion of the theory behind knowledge-based potentials is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the basic concept is straightforward: the more a given structure “resembles” the database of known structures (which are presumably correct), the “better” that structure is likely to be (Sippl, 1995; Godzik, 1996; Rojnuckarin and Subramaniam, 1999).

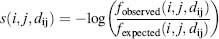

Broadly speaking, most statistical potential functions follow a simple formula: the structural feature of interest is quantified, this measurement is divided into bins (creating a histogram), and the “training set” (i.e., structures chosen from the Protein Data Bank specifically to represent the class of molecules being scored) is examined to see how the feature of interest is distributed. For example, if intermolecular atomic distances are being measured across a protein-DNA interface, it makes sense to divide the continuous range of realistic values (e.g., up to 10 Å) into 10 bins with 1 Å widths. If a diverse training set of protein-DNA structures were then examined to count the number of intermolecular contacts that fell within these bins, a histogram would be the result (Figure 25.1), and a simple score for an atom-atom pair is generated by taking the logarithm of the likelihood of each distance bin:

Here, i and j represent atom types on opposite sides of the protein-DNA interface, dij is the distance between them, and the numerator is the observed frequency of pairs between atom types i and j(separated by distance dij) in the training set. The denominator, in contrast, represents the ideal (or, in statistical terminology, the “expected”) value for this parameter and is commonly referred to as the “reference state” for the potential function.

The reference state greatly impacts score performance (Sippl, 1995), but its choice is somewhat arbitrary, and it is often impossible to know what this function should be a priori. The choice is usually justified empirically and as a result, a large research literature has focused on the reference state, exploring its impact on score performance (Sippl, 1990; DeWitte and Shakhnovich, 1996; Samudrala and Moult, 1998; Zhou and Zhou, 2002; Zhang et al., 2004a; Zhang et al., 2004b; Velec, Gohlke, and Klebe, 2005; Zhang, et al., 2005; Donald, Chen, and Shakhnovich, 2007; Robertson and Varani, 2007). For example, a naive implementation might assume that all distances are equally likely for any given atom pair (i.e., the reference state is a uniform distribution), whereas a more sophisticated approach may use the distribution of distances observed for all atom pairs as the reference distribution for any particular atom pair.

In practice, the existing statistical potentials for protein-nucleic acid interactions can be broadly grouped into two categories based on the structural features that they consider: orientation-dependent potentials (which exploit three-dimensional spatial and angular distributions) and distance-dependent potentials (which instead use one-dimensional data, such as interatomic and residue-residue distances). There are a small number of methods that do not fit cleanly into either category; these methods have thus far been targeted to specific classes of problems, such as the prediction of sequence targets for particular families of nucleic acid binding domains.

Figure 25.1. Creation of a distance-dependent statistical potential function. The process used to create a simple, distance-dependent statistical potential function is illustrated. Top: pair-wiseatomic distances are measured between protein (blue) and nucleic acid (gray) atoms across the binding interfaces of protein/DNA or protein/RNA complexes. Middle: atomic distances are tabulated for a large number of structures, and histograms are created for each unique atom-type pair. Bottom: the distance histograms are converted to scores using method-specific mathematical formalisms (e.g., a log-likelihood model, as in Eq. 25.1). Figure also appears in the Color figure section.

Orientation-Dependent Statistical Potential Functions. The earliest example of the application of a knowledge-based potential to protein/nucleic acid interactions can perhaps be found in the work of Kono and Sarai (1999), who used the geometric regularity of the DNA double helix to create local “reference frames” for the nucleotides, which were then used to count the number of amino acid alpha carbons in three-dimensional spatial bins surrounding the nucleotide bases. By converting these counts to frequencies and using these frequencies to estimate the likelihood of new protein-nucleic acid complex structures (generated by computationally “threading” new base sequences onto existing complexes), they were able to successfully predict the cognate DNA recognition sequences for a number of transcription factors of known structure. The success of this approach is largely due to the nonuniform distribution of amino acids about the DNA bases (e.g., lysine contacts to guanine tend to be clustered in the major groove of B-form DNA helices) (Luscombe, Laskowski, and Thornton, 2001), though the power of the method is striking, considering its simplicity.

More recently, Chen et al. developed an orientation-dependent hydrogen bonding function for protein-RNA interactions, and demonstrated its utility for predicting the amino acid sequences of RNA binding proteins (Chen et al., 2004). Unlike Kono and Sarai, this work used a complex, multiterm potential function that involved a mixture of statistical and physical terms. However, it further demonstrated that a database of protein-nucleic acid structures could be used to derive a statistical potential that measures the quality of hydrogen bonds across the protein-RNA interface. This objective was achieved by observing four structural features of hydrogen bonds (the donor-acceptor bond length, the bond angles at the donor and the acceptor atoms, and the planarity of the bond) and using the structural database to find the angular and distance distributions of these features (Kortemme, Morozov, and Baker, 2003). These distributions were converted to frequencies and used to infer the likelihood of new protein-RNA structures (in this case, generated by substituting new amino acids onto the backbones of known RNA binding proteins).

Distance-Dependent Statistical Potential Functions. The previous examples each used three-dimensional features of the protein-nucleic acid interface to develop statistical potential (scoring) functions. More recently, however, several groups have demonstrated that even a one-dimensional representation of the structural data is sufficient to discriminate native-like protein-DNA and protein-RNA complexes from nonnative structures. In particular, it appears that the interresidue and interatomic distances observed in the database of protein-nucleic acid structures contain sufficient information to identify cognate DNA and RNA recognition sequences, to discriminate native complex structures from sets of near-native “decoys,” and even to estimate the experimentally determined energetics of protein-nucleic acid binding. Despite their extreme simplicity, these “distance-dependent” methods are proving as powerful as the far more complicated, physically inspired potentials discussed previously.

A simple example of this distance-dependent approach was provided by Liu et al., who developed apotential function based on the observed separations between the beta carbons of amino acid residues and the geometric centers of nucleotide triplets, doublets and single nucleotides in protein-DNA structures (Liu et al., 2005). Liu et al. demonstrated that their approach could successfully predict the binding energies and cognate recognition sequences of a large number of DNA binding proteins; they further hypothesized that the use of nucleotide triplets allowed for the capture of higher order interactions, despite the use of one-dimensional distance information.

In a more complex approach, Zhang et al. (2005) developed a statistical potential function based on the observed intermolecular atomic distances in protein-DNA structures. This method mapped all the protein and DNA atoms in protein-DNA complex structures to 19 chemically derived atom types and determined a unique intermolecular distance potential for each of the 361 (=192) possible atom-type pairs. Despite training this method on a set of protein-ligand complexes (instead of protein-nucleic acid complexes), Zhang et al. demonstrated that their potential produced scores that correlate well with the experimentally determined dissociation (KD) constants for a collection of 45 protein-DNA complexes.

Most recently, two groups have independently demonstrated that all-atom, distance-dependent statistical potentials for protein-DNA interactions can achieve great predictive power by using only intermolecular distances at the protein/nucleic acid interface. Donald et al. showed that a quasichemical potential (wherein the reference state is determined by the relative frequencies of the different atom types) can accurately predict cognate DNA recognition sequences and relative binding energies (ΔΔG values) for a large number of experimentally characterized protein-DNA complexes (Donald, Chen, and Shakhnovich, 2007); Robertson and Varani (2007) demonstrated that an all-atom, distance-dependent potential (wherein a unique distance-dependent score was defined for each of nearly 14,000 intermolecular atom-type pairs) can achieve cognate binding sequence discrimination performance on par with physical potential functions. Both of these scoring functions rely on the large number of pair-wise atomic interactions made across a protein/nucleic acid interface (a number that grows proportionally to the square of the number of atoms in the interface) to derive a highly redundant description of the structural phenomena responsible for nucleic acid recognition. Thus, despite the simple one-dimensional data used to create the scores (i.e., interatomic distances), these methods are able to model chemical and structural phenomena that are actually three dimensional in nature. In other words, the massive redundancy of these scores allows them to capture higher order structural motifs with surprising fidelity.

Other Statistical Models. In addition to the orientation- and distance-dependent potentials discussed above, a few groups have explored the use of methods that do not fit cleanly into either category. In particular, Ge et al. developed a knowledge-based method for predicting the sequence-specific binding energies of polyamide molecules to DNA double helices, based on the observed positions of water molecules and amino acid atoms in known protein-DNA structures (Ge, Schneider, and Olson, 2005). This method clustered the atoms (water or amino acid) observed to hydrogen bond to DNA bases in their structure training set and used these structural clusters to determine 3D ellipsoid regions of likely drug-DNA hydrogen bonding interactions.

Finally, in an example of a prediction method targeted to a specific family of DNA binding proteins, Kaplan et al. developed a knowledge-based potential for Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins and used it to scan for transcription factor binding sites in the Drosophila genome (Kaplan, Friedman, and Margalit, 2005). The method is not general (it applies only to a single class of zinc finger proteins), nor is it truly a structure-based potential (it does not make direct use of structure data), but it exploits the well-understood regularity of the Cys2His2 family of zinc finger proteins to construct a probability model of DNA recognition. Thus, it represents an interesting application of structural knowledge to the prediction of transcription factor binding sites.

FLEXIBILITY IN PROTEIN/NUCLEIC ACID COMPLEXES

An important, largely unsolved problem inherent to the structure-based prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions lies in the treatment of molecular flexibility, which is frequently observed in protein-RNA complexes, but is also important to protein-DNA interactions. Although some simulation methods (such as molecular dynamics or gradient-based minimization techniques) explicitly allow for the representation of small motions at the protein-nucleic acid interface, there is good reason to believe that the molecular movements involved in nucleic acid sequence recognition are larger than can be accurately modeled using these methods alone (Dickerson, 1998). For this reason, several groups have introduced methods to incorporate protein flexibility into the problem of protein-DNA and protein-RNA interface prediction. For example, Endres et al. (2004) used the AMBER force field, in combination with a dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm for protein side-chain packing, and demonstrated that this method can predict the consensus binding sequence of the Zif268 zinc finger transcription factor. However, their results also suggested that the use of rotamer packing may have negatively impacted the performance of their method, leaving open the question of the effectiveness of the flexibility model.

In a second example, when Havranek et al. applied the ROSETTA protein design algorithm (Kuhlman and Baker, 2000) to protein-DNA complexes, they demonstrated that their Monte Carlo-based approach to side-chain rotamer packing can predict native-like protein sequences from the structures of protein-DNA complexes (Havranek, Duarte, and Baker, 2004), and they later successfully used the method to guide a localized redesign of the I-MsoI homing endonuclease protein (Ashworth et al., 2006). However, when Morozov et al. used the same approach to predict ΔΔG values for a large set of experimentally characterized mutations to protein-DNA complexes, the performance of the method was negatively impacted by the introduction of protein flexibility. When side-chain packing was enabled, the ROSETTA potential did no better than a control method, which counted the number of intermolecular contacts observed at the protein-DNA interface. Also, an attempt to incorporate a limited model of DNA flexibility into their software was found to further degrade the performance of the approach (Morozov et al., 2005).

Therefore, to date, no group has successfully demonstrated a method that improves the prediction of sequence-specific protein-nucleic acid interactions through the incorporation of molecular flexibility. Even relatively conservative methods (such as algorithms for the prediction of protein side-chain conformations) can achieve only limited accuracy (Dunbrack, 2002). Thus, the modeling of molecular flexibility represents not only a fertile area of future research, but also a significant obstacle. This issue must be addressed if current scoring functions are to be reliably applied to computationally intensive problems, such as the structure-based annotation of genome sequence, or the rational design of nucleic acid binding proteins with new sequence specificities.

For protein flexibility, the path toward progress in this area is at least somewhat clear—in addition to the large research literature surrounding the molecular dynamics simulation of proteins (Chapter 37), there have also been a number of efforts to investigate the use of protein flexibility models for computational protein design (Desjarlais and Handel, 1999; Larson et al., 2002; Kuhlman et al., 2003; Kuhlman and Baker, 2004; Saunders and Baker, 2005; Ambroggio and Kuhlman, 2006a; Ambroggio and Kuhlman, 2006b; Bui et al., 2006; Georgiev and Donald, 2007), as well as for small-molecule docking and structure-based drug design (Claussen et al., 2001; Cavasotto and Abagyan, 2004; Polgar and Keseru, 2006). However, research into models of nucleic acid flexibility is less well established, and aside from MD simulations of protein/nucleic acid complexes (for example, see Lebrun and Lavery, 1999; Lebrun, Lavery, and Weinstein, 2001; Thayer and Beveridge, 2002; Marco, Garcia-Nieto, and Gago, 2003; Gorfe, Caflisch, and Jelesarov, 2004; Gutmanas and Billeter, 2004; Arauzo-Bravo et al., 2005; Zhao, Huang, and Sun, 2006; Mendieta et al., 2007), there have been relatively few efforts to model the flexibility of nucleic acid molecules or their complexes with proteins.

Encouragingly, several groups have made careful studies of the observed flexibility of DNA molecules in protein/DNA complex structures (Olson et al., 1995; Dickerson, 1998; Olson et al., 1998; Lafontaine and Lavery, 2001; Steffen et al., 2002a; Gromiha et al., 2005). Furthermore, Murray et al. (2003) recently observed that the RNA backbone appears to adopt a limited number of “rotameric” conformations that might facilitate the automated prediction of three-dimensional structures for RNA molecules. These studies may represent fruitful starting points for future research into nucleic acid flexibility, but there is a great deal of work left to be done before flexibility models can be incorporated successfully into predictive models of protein/nucleic acid interactions.

APPLICATIONS

The structure-based prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions is a new field, and there are still few examples of practical applications—particularly those with large-scale experimentally validated results. Nevertheless, research in the field is growing rapidly, and existing publications already offer promise that the structure-based analysis and prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions will become a valuable tool for biologists seeking new sources of insight and guidance for experimental design.

Molecular Docking

An application of structural analysis that has been successfully demonstrated is the prediction of protein-DNA and protein-RNA interactions through the computational docking of protein and nucleic acid structures. Computational docking is a well-established technique in the study of protein/protein and protein/small-molecule interactions (Chapters 26 and 27), and because it is relatively easy to conduct rigid-body binding simulations of molecular structures, this was one of the earliest tests applied to protein- nucleic acid systems. Nearly a decade ago, Knegtel et al. applied their Monte Carlo-based docking method (MONTY) to the prediction of protein-DNA interactions. Their research incorporated both protein side-chain (Knegtel et al., 1994a) and DNA flexibility (Knegtel, Boelens, and Kaptein, 1994b) but demonstrated their methods successfully on only a few protein-DNA complexes. Later, Aloy et al. (1998) used the innovative rigid-body search algorithm of FTDock to predict protein-DNA interactions for a larger number of complexes and subsequently extended the method to incorporate protein side-chain flexibility at the protein-DNA interface (Sternberg et al., 1998). Most recently, Robertson and Varani (2007) used the FTDock rigid-body method to validate a knowledge-based potential for protein- DNA interactions and showed that the score was able to significantly improve upon the FTDock results. Chen et al. also achieved good docking decoy discrimination performance for protein-RNA complexes using the ROSETTA docking method (Monte Carlo-based rigid-body docking, coupled with protein side-chain flexibility (Gray et al., 2003)). Finally, in one of the most advanced examples of protein/nucleic acid docking to date, van Dijk et al. (2006) used their HADDOCK method to conduct fully flexible docking simulations of three protein-DNA complexes. By alternating rounds of rigid-body docking with computationally intensive MD simulations of thebest-scoring docking decoys, they were able to predict reasonably accurate models of protein-DNA complexes starting from structures of their unbound components.

Despite these initial efforts, there are considerable practical limitations to the prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions using docking simulations. In particular, only a few attempts have been made to dock unbound structures of protein and DNA molecules with mixed results. Because of the importance of conformational change in the process of protein/ nucleic acid recognition, our understanding of molecular motion limits our ability to accurately model protein-nucleic acid interactions. The flexible nature of DNA and RNA molecules, the prevalence of induced fit (wherein the protein and/or the nucleic acid molecule change shape to accommodate binding), and the importance of indirect recognition mean that any generally useful docking method for protein-DNA or protein-RNA interactions will have to incorporate models of molecular flexibility that are more advanced and robust than currently available.

Analysis of Direct and Indirect Recognition

The computational analysis of protein-DNA and protein-RNA structures can be used to develop and explore hypotheses about the mechanisms ofprotein-nucleic acid recognition that cannot be easily addressed via experiment. For example, a number of studies have used computational models to quantitatively investigate the importance of direct and indirect recognition in sequence-specific protein/nucleic acid interactions. In this case, the ability to computationally model protein/nucleic acid complexes allows for investigation of a problem that is very difficult to directly assess using experimental approaches. Direct recognition (recognition due to direct atomic interactions across a protein/nucleic acid interface) can, in theory, be distinguished from indirect readout (recognition of sequence-dependent distortions in nucleic acid structure) by quantifying the relative contributions of inter- and intramolecular interactions to protein-DNA binding free energy. Paillard and Lavery (2004) and Gromiha et al. (2005) have both performed large-scale analyses of this important problem, using different potential functions, and found that the contributions of direct and indirect recognition vary significantly from structure to structure. Previously, Steffen et al. showed that they could partially predict the preferred binding sites of the integration host factor (IHF) protein by calculating the energies of bending for different DNA sequences (Steffen et al., 2002a; Steffen et al., 2002b), using a statistical potential function based on the DNA geometric parameters described by Olson et al. (1995, 1998). A number of other structure-based analyses have investigated this question for different protein-DNA complexes (Gorfe, Caflisch, and Jelesarov, 2004; Arauzo-Bravo et al., 2005; Dixit, Andrews, Beveridge, 2005; Aeling et al., 2006; Napoli et al., 2006; Aeling et al., 2007).

Structure Refinement

Another interesting yet largely unexplored application—particularly for statistical potentials—lies in the refinement of protein-nucleic acid structures. Traditionally, the software used to create crystallographic and NMR structures has employed physics-based potentials during refinement. However, Kuszewski et al. recently developed a statistical potential function (DELPHIC) that describes the relative orientations of dinucleotide steps. They used this potential to refine several NMR structures of DNA and RNA molecules (Kuszewski, Schwieters, and Clore, 2001; Clore and Kuszewski, 2003), and demonstrated that the potential was able to improve the quality of the refined structures. They also demonstrated that the use of a database-derived potential did not reduce their ability to obtain correct refinement for noncanonical nucleic acid structures. These results suggest that statistical potentials may find application in the refinement of molecular structures, particularly when the experimental data are of limited quality (structures with low crystallographic resolution, poorly defined NMR structures, and so on).

Structure-Based Genome Annotation

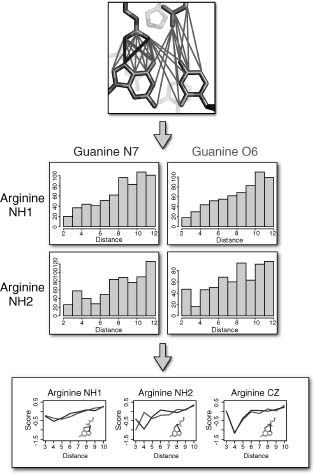

One of the most compelling applications of structure-based methods for the prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions is also one of the most obvious: if it were possible to accurately predict the sequence recognition preferences of a protein from its structure, it should be possible to use that structure to predict the binding sites of the protein within a genome. In fact, the idea of using structures of protein-nucleic acid complexes to annotate genomes for transcription factor (and other) binding sites is so compelling that nearly every publication in the field has incorporated some sort of binding sequence scanning experiment as a methodological test. For example, Kono and Sarai (1999) used their statistical potential to predict the recognition sequences of 25 different DNA binding proteins (to varying degrees of success), and also demonstrated the method’s ability to identify five of the six known binding motifs of the MAT a1/α2 protein in the upstream region of a known target gene. Liu et al. used their distance-dependent statistical potential to find the known binding sites of the cyclic AMP regulatory protein (CRP) in the Escherichia coli genome (Liu et al., 2005). Paillard and Lavery (2004) used their physics-based potential to reproduce the consensus binding sites of multiple protein-DNA complexes, while Morozov et al. (2005) used their method to predict position weight matrices for a number of DNA binding proteins. Finally, Robertson and Varani used their statistical potential function to recapitulate the cognate recognition sequences of 52 different DNA binding proteins (Robertson and Varani, 2007) (Figure 25.2). While many important aspects of protein/ nucleic acid interfaces were ignored in these early tests (for example, most of these efforts did not consider interfacial water molecules in their analyses, and few incorporated any type of interface flexibility), it is nonetheless clear that structure-based genome annotation is rapidly becoming a reality.

More recent research is beginning to tackle the even more difficult—but considerably more important—problem of predicting nucleic acid binding sequences for proteins for which only homology models are available. Morozov and Siggia (2007) recently employed a simple, contact counting method to predict the binding preferences of 57 Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factors of previously unknown structure. This approach represents a leap forward in the application of structural models to biological research by enormously expanding the number of interesting targets well beyond those proteins for which high-resolution structures are available.

Figure 25.2. A successful structure-based prediction of a DNA recognition sequence. An example of a successful prediction of a DNA recognition sequence from structure is shown. Left: the crystal structure of the Zif268 DNA binding protein, along with its consensus DNA recognition sequence. Right, top: the sequence logo (Schneider and Stephens, 1990) derived from experimentally determined DNA binding preferences for the protein (Morozov et al., 2005; Swirnoff and Milbrandt, 1995). Right, bottom: a sequence logo calculated directly from the protein/DNAcomplex structure using a statistical potential function (Robertson and Varani, 2007).

Rational Protein Design

If a structure-based model of a DNA or RNA binding protein is accurate enough to be used to predict the cognate nucleic acid recognition sequences for that protein, then it may be possible to use the model to solve the converse problem—the prediction of a protein sequence that will optimally bind a given nucleic acid sequence. This is simply are statement of the protein design problem, as applied to nucleic acid binding proteins. While there has been an enormous amount of research dedicated to the structure-based design (or directed evolution) of certain classes of nucleic acid binding proteins (Pomerantz, Sharp, and Pabo, 1995b), particularly for zinc finger proteins (Pomerantz, Pabo, and Sharp, 1995a; Isalan, Choo, and Klug, 1997; Kim et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1997; Kim and Pabo, 1998; Pomerantz, Wolfe, and Pabo, 1998; Wolfe, Ramm, and Pabo, 2000; Peisach and Pabo, 2003; Wolfe, Grant, and Pabo, 2003; Mandell and Barbas, 2006; Papworth, Kolasinska, and Minczuk, 2006; Nomura and Sugiura, 2007), there are still no general-purpose methods that can successfully design protein sequences that will fold into conformations with a desired DNA or RNA binding ability. Given that designed zinc finger proteins have considerable potential as therapeutic compounds for human diseases (Klug, 2005; Papworth, Kolasinska, and Minczuk, 2006), there are clearly many potential applications for any method that can solve this more general problem.

Recently, a few groups have been making progress toward this goal using structure-based protein design algorithms. For example, Havranek et al. used the ROSETTA protein design software to recapitulate the native amino acid sequences of DNA binding proteins given their protein backbone structures, as well as the structures of their bound DNA molecules (Havranek, Duarte, and Baker, 2004), while Chen et al. (2004) successfully applied the same approach to RNA binding proteins. These results demonstrate that the ROSETTA potential can largely (though by no means perfectly) identify the native amino acid sequences of protein-nucleic acid complexes as optimal for their bound structures. This is a necessary condition for any structure-based protein design algorithm.

To date, the ROSETTA software has been used to redesign two different nucleic acid binding proteins: Dobson et al. (2006) used the method to design a variant of the U1A RNA binding protein, while Ashworth et al. (2006) redesigned the I-MsoI homing endonuclease (a DNA binding protein). Dobson et al. demonstrated that the completely redesigned U1A molecule (with approximately 30% sequence identity to the wild-type protein) was able to fold into a native-like structure, although no attempt was made to retain the RNA binding function of the redesigned protein. Ashworth et al. used a more conservative design strategy for the I-MsoI protein-DNA complex, introducing two amino acid mutations at the protein-nucleic acid interface; they demonstrated that the redesigned protein bound specifically to a DNA sequence with a single guanine/cytosine base pair transversion (relative to the cognate recognition sequence). Thus, although these early tests of protein design methods have been promising, there is still a great deal of work to be done before it is possible to reliably design nucleic acid binding proteins of all classes with arbitrary sequence specificity.

Both of these attempts at structure-based protein design relied exclusively upon structural information (coupled with the energetic analysis provided by a physical potential function) to make their predictions. However, a few groups have demonstrated a phenomenon that may be useful for a more directed type of protein design: significant correlations can be observed between patterns of protein sequence evolution within families of nucleic acid binding proteins and the evolutionary patterns of the nucleic acid recognition sequences of those same proteins (Lichtarge, Yamamoto, and Cohen, 1997; Mirny and Gelfand, 2002b; Raviscioni et al., 2005). In particular, Raviscioni et al. demonstrated that for 12 different families of transcription factors, the evolutionarily most important protein residues of the families tended to interact with the most conserved base pairs of their DNA recognition sequences. They subsequently used this information to experimentally alter the sequence specificity of a zinc finger transcription factor (Raviscioni et al., 2005). Thus, it appears that this so-called “evolutionary trace” method (Lichtarge, Bourne, and Cohen, 1996) (and other closely related approaches) can guide the rational design of nucleic acid binding proteins. The method can highlight the most relevant protein residues for nucleic acid recognition and also suggest protein mutations that will lead to desired changes in sequence specificity. Coupled with physics-based or statistical models of protein-DNA interactions, evolutionary trace methods may prove to be a powerful tool for the rational, structure-based design of DNA and RNA binding proteins.

FUTURE WORK AND CRITICAL CHALLENGES

Steady increases in computer power, the size of the structural database, and our improved understanding of protein, DNA, and RNA biochemistry are rapidly allowing the structure-based modeling and prediction of protein/nucleic acid interactions to become realistic prospects. This field has experienced impressive advancements within the last decade; 10 years ago, research into protein-nucleic acid recognition was dominated by the misguided search for a “recognition code,” but today it is possible to choose between multiple successful methods to predict, design, and model protein-DNA and protein-RNA interactions at the atomic level. However, all of these methods have limitations, and successful applications and experimentally validated tests are still rare. A great deal of work remains to be done if the promise of this research is to be fulfilled. In particular, at least three major areas of research must be advanced before the modeling of protein-nucleic acid interactions can become a widely used predictive tool: (1) the accuracy of existing potential functions must be enhanced; (2) the ability to simulate molecular flexibility of protein, DNA and RNA molecules must be improved; and (3) additional details of the molecular interface (e.g., water, metals/ligands, base stacking, pi-pi and cation-pi interactions) must be incorporated into the current models.

As our understanding of the dynamics and details of protein-nucleic acid recognition advances, deficiencies in our understanding of the forces and interactions involved in these processes will undoubtedly emerge. At the moment, it appears that even the simplest statistical potentials perform as well as considerably more complex molecular dynamics force fields in many situations: Will this continue to be true as simulations increase in complexity and detail, and the sampling problem of large-scale simulations become less acute? Perhaps more complex models of electrostatics, solvent effects, and hydrogen bonding will be necessary to accurately model detailed interactions at molecular interfaces. However, it is also possible that database-derived potentials may be able to implicitly capture these effects as well as the best physics-based methods.

As noted above, even the current best methods for simulating protein-nucleic acid interactions can capture only small amounts of molecular flexibility, such as protein side-chain rearrangements or (in the case of molecular dynamics methods) small-scale molecular motions. However, even these limited techniques take prohibitive amounts of computer time and thus far have been unable to significantly improve simulation results in most circumstances. When one considers that protein-DNA and (particularly) protein-RNA interactions often involve large-scale conformational rearrangements of both protein and nucleic acid molecules (Leulliot and Varani, 2001), the need for improved conformational simulation techniques becomes acute. Clearly, new methods need to be developed to accurately sample or simulate the motions of protein and nucleic acid molecules as they interact. Moreover, these new methods must be computationally tractable for large-scale simulations if they are to be usefully applied to problems such as structure-based genome annotation or protein/nucleic acid interface redesign.

In addition to limitations in the ability to simulate molecular motions, it is clear that even the current best models miss important details of the protein/nucleic acid interface. For example, few of the methods discussed in this chapter explicitly consider the role of interface water molecules or metal ions at the molecular interface, although nearly every known protein-DNA and protein-RNA complex depends on the precise positioning of these molecules to mediate sequence-specific recognition. The associated questions are numerous: How do water molecules position themselves in a protein-nucleic acid interface? What are the enthalpic, entropic, and free energy consequences of water- or ion-mediated interactions with nucleic acid molecules? Can interactions with highly conserved interfacial water molecules be displaced through the careful redesign of hydrogen bonding networks? Water molecules represent just one area for which our understanding of the details of protein-nucleic acid recognition is poor. From the importance of intra- and intermolecular stacking interactions involving carbon ring systems (i.e., pi-pi and cation-pi interactions) to the role of conformational entropy in binding free energy, there are other important characteristics of these interfaces that remain underinvestigated.

The structure-based modeling of protein-DNA and protein-RNA interactions not only is an exciting field, with many interesting and relevant scientific implications, but also has considerable challenges. Within the last decade, our understanding of sequence-specific protein/nucleic acid recognition has leapt forward, and a number of practical applications have been demonstrated in principle, despite the relatively simple modeling techniques used so far. It is very likely that significant advances will be made in our ability to predict, design, and simulate critically important molecular interactions. As these open questions are addressed, we anticipate that the prediction of protein-nucleic acid interactions will emerge as an important, widely used application of structural bioinformatics.