26

PREDICTION OF PROTEIN-PROTEIN INTERACTIONS FROM EVOLUTIONARY INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION

The more we know about the molecular biology of the cell, the more we see genes and proteins as part of networks or pathways instead of as isolated entities and understand their function as a variable of the cellular context. To fulfill this new paradigm, genomic sequences offer a catalog of building blocks, and protein interactions provide the first information for the challenging task of understanding the functions of these genes and proteins within their situation in networks and pathways. To further refine the information on the context and timing in which these observed biological functions take place, additional insight from genetic regulatory mechanisms and genetic specificity (cell-type specificity, individual differences, etc.) will become increasingly important.

The study of protein interactions can be divided into two complementary aspects, the determination of the residues or regions implicated in the interactions and the deciphering of the identity of the interaction partners (which proteins interact with which ones). These two problems have been typically addressed by biophysical and biochemical techniques, such as binding studies (chromatographic isolation of complexes, coimmunoprecipitation, protection, cross-linking studies, etc.) and indirect genetic methods (gene suppression studies, systematic mutagenesis, and interspecies exchanges). The development of genomic and postgenomic technologies has changed the panorama considerably, with the possibility of obtaining systematically massive amounts of data about protein interactions. Progress has been done in the automation of experimental approaches such as yeast-two-hybrid based methods and mass spectrometry determination of components of macromolecular complexes. At the same time, a number of new bioinformatics techniques have been developed based on the considerable amount of sequence and genomic information that is being accumulated in databases. In the following, we review the status of these bioinformatics approaches to the study of protein interactions, including the prediction of interaction partners and protein-protein binding regions.

Evolutionary Features Related with Structure and Function

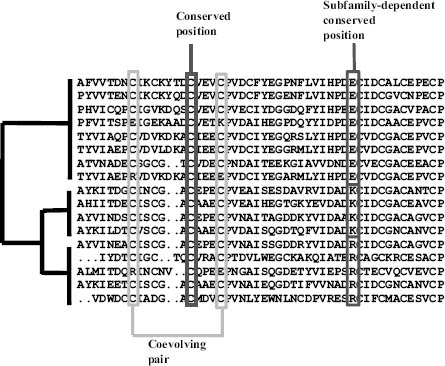

Multiple sequence alignments (MSA) represent the main source of evolutionary information available. The relation between equivalent positions of homologous proteins compiles the result of the changes allowed by the evolution of the corresponding proteins at different positions. The interplay of structural and functional requirements contributing to the stabilization of natural variants creates complex patterns of mutational behavior of the positions that have been exploited by a number of computational methods in the search for structural and/or functional constraints (Figure 26.1).

Conserved Positions. The information most widely extracted from multiple sequence alignments is related with conserved positions (Zuckerkandl and Pauling, 1965). These invariable positions are interpreted as important residues for the structure or function of the protein since apparently changes were disallowed during evolution (Figure 26.1). Conserved positions usually are located in structural cores (i.e., structurally important positions) and active/binding sites (i.e., positions directly involved in protein function). Although the problem of locating conserved positions could look trivial at first sight, there are many different approaches that produce different results depending, for example, on the treatment of conservative changes (Valdar, 2002). Modern methods for detecting conserved sites incorporate complex evolutionary models taking into account the phylogeny of the sequences in the MSA (Pupko et al., 2002), so as to avoid artifacts due to the peculiarities or uneven distribution of sequences in the alignment (i.e., highly similar sequences resulting in most of the positions being conserved). Despite a number of attempts to analyze the relationship between binding sites, conserved positions, and type of amino acid in those positions (Villar and Kauvar, 1994; Ouzounis et al., 1998), the complex nature of the relations indicates that much remains to be done in this area.

Figure 26.1. Sequence features related with structure and function extracted from multiple sequence alignments. MSA and its implicit phylogeny are shown. Conserved positions are invariant throughout all the sequences. In the family-dependent conserved positions, a different amino acid type is conserved within each one of the subfamilies. For coevolving pairs of positions, changes in one of the positions are correlated with the corresponding changes in the other.

Family-Dependent Conserved Positions. There is a more subtle kind of conservation, the family-dependent conservation. These positions are typically conserved in the subfamilies that form well-defined branches of the phylogenetic tree and differ in the chemical type of the amino acids that characterize each subfamily (Figure 26.1). We have previously used the term tree-determinants to describe these positions given their drastic in fluence in the structure of the corresponding phylogenetic trees. Family-dependent conserved positions would be most likely related with the specific features of each subfamily that in most cases turn out to be the differential binding to other proteins and substrates.

One of the first approaches to the detection of this kind of functional residues, implemented in the sequencespace program, was developed by Casari, Sander, and Valencia (1995) and later followed by a plethora of other methods (Lichtarge, Bourne, and Cohen, 1996; Andrade et al., 1997; Mesa, Pazos, and Valencia, 2003; Kalinina et al., 2004; Mihalek, Res, and Lichtarge, 2004). The underlying principle in all these methods is the detection of positions in multiple sequence alignments with a differential conservation in the different groups of sequences that form part of a larger protein family. All these methods use the subfamily classification implicit in the phylogeny represented by the MSA (Figure 26.1). Recently, some methods were developed that do not rely on that implicit classification but are able to incorporate an external classification of the sequences according to some known functional property (Hannenhalli and Russell, 2000; Pazos, Rausell, and Valencia, 2006).

Coevolving Positions. Another sequence-based approach for the prediction of protein structure and molecular complexes is based on the detection of correlated mutations in multiple sequence alignments and their use as distance constraints between residues belonging to the same or different proteins. Correlated mutations correspond to pairs of positions with a clear pattern of covariation (Figure 26.1). The underlying evolutionary model for explaining their relation with space neighboring assumes that part of the detected correlated pairs correspond to compensatory mutations, where in particular sequences of the multiple sequence alignments the mutation of one residue was compensated along the evolution by a mutation of a neighbor residue, most likely to keep proteins (or protein complexes) in permissible limits of protein stability. Coevolving positions have been demonstrated to have an important functional role together with conserved positions (Socolich et al., 2005).

The method proposed in 1994 (Göbel et al., 1994) for detecting these types of positions was a weak predictor of proximity between residues in protein structures. Despite their low accuracy, these predicted contacts have been demonstrated to be useful, for example, in filtering structural models (Olmea, Rost, and Valencia, 1999) or driving ab initio simulations (Ortiz et al., 1999).

PREDICTION OF INTERACTING REGIONS

Structure and Sequence Characteristics of the Interaction Sites

In general, the interaction surface (interface) is difficult to distinguish from the rest of the surface, from either a sequence or structure point of view. The interaction sites are not clearly enriched in any particular type of amino acid (Chakrabarti and Janin, 2002). Nevertheless, some particular types of complexes do have preferences for some amino acids at the interfaces, that is, hydrophobic residues in homodimers (Jones and Thornton, 1997; Ofran and Rost, 2003a). Similarly, structural characteristics are only discriminative for some type of complexes, that is, nonplanar interfaces for enzyme inhibitor and large planar interfaces for homodimers (Jones and Thornton, 1997; Lo Conte, Chothia, and Janin, 1999). For these reasons, complex machine learning systems are required for dealing with the problem of predicting interaction sites from sequence or structure information.

Structure-Based Methods

The problem of determining the physical structure of protein complexes when the structure of the members is known is part of the problem of docking molecules, such as proteins with small molecules (Chapter 27). Despite the considerable efforts that have gone in solving this problem, directed at the design of new drugs, the solutions in the case of protein-protein interaction are still far from optimal.

Despite these difficulties, various groups have achieved considerable progress in the development of physical docking programs. Most of the current approaches consider proteins as rigid bodies and have the physical matching of the surfaces as their main guide. Only a few approaches integrate conformational flexibility, allowing the interacting surfaces to adapt one to the other, normally at the expenses of reducing the search space for possible interacting surfaces. Some programs take into account other features for predicting regions of interaction, like hydrophobicity or electrostatics (Chapter 24). For recent reviews on docking, see Schneidman-Duhovny, Nussinov, and Wolfson (2004) and Gray (2006). An interesting effort to compare the various protein docking approaches in a blind test is organized by Janin et al. (CAPRI: http://capri.ebi.ac.uk/). The results of this experiment, if enough structures of protein complexes become available for the comparison, will be important for updating our view of the capability of current docking methods. A pressing question now is that the structural genomics efforts are on the way to solve a substantially larger number of isolated proteins and protein domains (Chapter 40).

There are other structure-based techniques for predicting interacting regions apart from physical docking. Some approaches are based on the fact that in many cases binding or active sites are energetically unstable. This is due to many factors, including the need to put together energetically unfavorable combinations of residues due to functional requirements (e.g., two residues with the same charge in a catalytic site) or to maintain unstable interacting regions that are stabilized upon binding, favoring in this way the bound form in the binding equilibrium. The uneven distribution of the stabilization energy in proteins has been related with binding sites and cooperativity effects (Luque and Freire, 2000). Relationships between functionally important residues and those that negatively contribute to the electrostatic stabilization energy have also been found (Elcock, 2001).

New concepts taken from graph theory have been applied to the detection of interaction sites in 3D structures. Within these methods, a protein structure is represented as an undirected graph where the nodes are the residues and the edges represent contacts between them. Within this graph, residues (nodes) with special connectivity characteristics such as high “centrality” have been associated with functional and binding sites (Del Sol and O’Meara, 2005).

The combined data on massive protein interactions (see the section “Experimental Techniques and High-Throughput Applications”) and structural information can be mined in the search for short motifs or patterns frequently involved in interactions (Neduva and Russell, 2006). These motifs can be used for predicting new interacting regions.

With the increasing availability of protein 3D structures, methods that use structural alignments for predicting binding and functional sites are emerging. These methods are conceptually similar to the ones based on sequence alignments (see the section “Sequence-Based Methods”) but use structural alignments to relate more distant proteins (Pazos and Sternberg, 2004; Chung, Wang, and Bourne, 2006).

Sequence-Based Methods

Ab Initio Methods. We term ab initio methods in this context as methods that only use the sequence of a protein to predict residues involved at the binding interface for intermolecular recognition.

This category of methods includes the detection of intrinsically unstructured segments in protein sequences, also termed “disordered regions”; see Bracken et al. (2004) and Chapter 38. To some extent opposing the paradigm that structure determines function, what determines the function of these proteins is actually their lack of structure. The functional importance of these regions arises from their frequent involvement in protein-protein interactions. In many cases, these unstructured segments become structured on binding, favoring the bound form of the interaction equilibrium. This type of entropy-driven interaction has the unique specificity/affinity characteristics required for some biological complexes (Vucetic et al., 2003). These intrinsically unstructured regions are to some extent related to the low complexity segments in the primary sequence (Wootton and Federhen, 1996; Romero et al., 2001). Nevertheless, specific predictors have been developed to locate these regions (Iakoucheva and Dunker, 2003; Ward et al., 2004).

Another method that uses a single sequence as the primary input to identify interacting regions is the neural network (NN) developed by Ofran and Rost (2003b). This NN is trained with sequence segments of interaction sites, and it correctly predicts at least one interaction site for 20% of the complexes in its test set.

Methods Based on Multiple Sequence Alignments. Most sequence-based methods for predicting protein interaction regions use evolutionary information in the form of multiple sequence alignment. For example, Ofran and Rost’s method commented in the previous section obtains better results when MSA-derived information is incorporated (Ofran and Rost, 2007).

The use of evolutionary conservation, a strategy often employed to identify residues of functional importance, has also been used for detecting interaction sites. Although the best results are obtained when combining conservation with structural information (see the section “Hybrid Methods”), we include in this section of sequence-based methods predictors that combine residue conservation with predicted structural features that are often based on MSA. For example, ConSeq uses a sophisticated calculation of conservation together with predicted solvent accessibility for predicting functional residues and binding sites (Berezin et al., 2004).

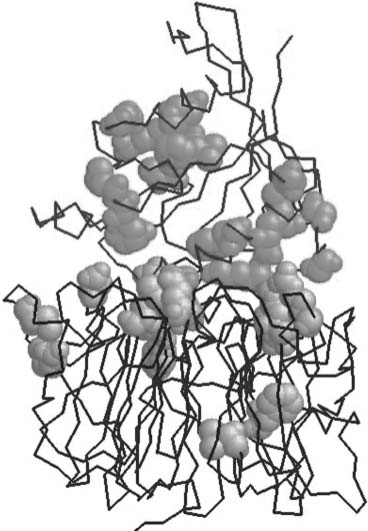

The relation between tree-determinant residues (see the section “Family-Dependent Conserved Positions”) and interacting surfaces has been analyzed in detail in some well-characterized systems (Casari, Sander, and Valencia, 1995; Lichtarge, Bourne, and Cohen, 1996; Atrian et al., 1997; Pazos et al., 1997b; Pereira-Leal and Seabra, 2001). More importantly, it has also been demonstrated by direct experiments how exchanging tree-determinant residues between protein subfamilies lead to a switch in the observed specificity of interaction of the corresponding proteins. This demonstration has been performed on two different proteins in the ras family of small GTPases (Stenmark et al., 1994; Azuma et al., 1999). In Figure 26.2, the tree-determinant residues extracted from the multiple sequence alignments of Ran and Rcc1 are marked in the structure of the complex formed by these two proteins. It can be seen that many of these residues, predicted from sequence information alone and before the structure of the complex was solved, map in the interaction surface, especially in Rcc1.

Figure 26.2. Complex between Ran (upper chain) and Rcc1 (lower chain) marking the treedeterminant residues (in spacefill) for the two proteins (PDB ID: 1I2M). Tree-determinant residues were calculated with the sequencespace algorithm (Casari, Sander, and Valencia, 1995). Figure courtesy of Juan A.G. Ranea. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

Coevolving positions (see the section “Coevolving Positions”) have also been used for detecting interfaces (Pazos et al., 1997a; Yeang and Haussler, 2007; Madaoui and Guerois, 2008). In spite of the weak power of correlated mutations in predicting neighboring residues, it was demonstrated that, in many cases, it is enough to discriminate the right arrangement of two protein chains from many alternatives (Pazos et al., 1997a). Recently, it has been argued that the observed correlation appears only in permanent (not transient) complexes (Mintseris and Weng, 2005).

Hybrid Methods

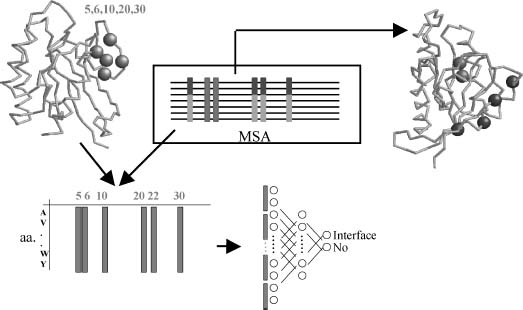

Methods that incorporate both structural and sequence information to predict interaction surfaces demonstrated significant improvement from the equivalent ones that use only sequence information. The simplest way of combining sequence and structural information for predicting binding regions is by simply mapping the sequence-based predicted sites (conserved, family-dependent conserved, correlated, etc.) into the 3D structure of the protein to assess whether the predicted positions have the structural characteristics expected for a functional or binding site (clustered or accessible to the solvent) (Figure 26.3). For example, the ConSurf program looks for conserved residues that map in the surface of the protein, taking into account the distribution of sequences in the MSA for calculating conservation (Armon, Graur, and Ben-Tal, 2001). Panchenko et al.’s method also looks for clusters of conserved residues (Panchenko, Kondrashov, and Bryant, 2004). The method developed by Aloy et al. searches for conserved apolar residues that cluster in the surface of the protein (Aloy et al., 2001). Distant sequences in the MSA are successively removed until the set of conserved residues forms a cluster. Landgraf et al.’s method looks for surface regions of the protein following the same phylogeny as the whole family (Landgraf, Xenarios, and Eisenberg, 2001). Structural information is used to define those regions (as sets of residues close in the surface of the protein). 3D information can also be incorporated in other methods for detecting family-dependent conserved positions simply by imposing clustering (Madabushi et al., 2002; Yao et al., 2003). Some methods map sequence conservation on 3D structures but using a simplified alphabet that reflects the functional groups of the amino acids instead of considering all the 20 (Innis, Anand, and Sowdhamini, 2004).

Figure 26.3. Prediction of binding sites combining multiple sequence alignments (MSA) and structural information. Conserved positions in the MSA (black) and family-dependent conserved positions (gray) have been extensively used as predictors of interaction and functional sites. If available, structural information can be used a priori or a posteriori. If used a priori (left), the structure is used to define surface patches (gray). The sequence features of members in this patch are encoded (i.e., amino acid frequency vectors in this case) and used as input features to a machine learning system such as a neural network (bottom). The machine learning system is trained to distinguish patches involved in interaction from non-interacting ones. A posteriori (right), the structure can be used to assess whether a set of positions predicted from sequence has the characteristic 3D features of a binding site such as being clustered in proximity and exposed to the solvent.

A much direct way of combining sequence and structural information for predicting binding sites is by using machine learning systems, such as neural networks or support vector machines (SVM). This general strategy was introduced by Zhou and Shan (2001) and Fariselli et al. (2002), and later followed by many other authors (Koike and Takagi, 2004; Bordner and Abagyan, 2005; Bradford and Westhead, 2005). These methods use the structure of a protein to define surface patches of neighbor residues and the multiple sequence alignment to obtain the sequence profiles (or other sequence-based features) for the members of the patch (Figure 26.3). The machine learning system is then trained with that information for a training set of proteins with known interaction surfaces. After the training process, surface patches (plus their corresponding sequence features) of proteins with known structure but unknown interaction surface are presented to the system to identify which surface patches are involved in intermolecular recognition. The reported accuracy of these methods is higher than 70%. Nevertheless, it is difficult to test these methods and compare their performance due to the absence of a good test set of protein interfaces (nonredundant in sequence and structure, covering all types of complexes, etc).

PREDICTION OF INTERACTION PARTNERS

Experimental Techniques and High-Throughput Applications

The experimental approaches for the determination of interaction partners have undergone dramatic improvements during the last few years, particularly through the systematic application of different strategies based on the yeast-two-hybrid protocol (Fields and Song, 1989) and the tandem affinity purification (TAP) of complexes followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (Gavin et al., 2002). These approaches were used to determine large proportions of the interactomes of a number of model organisms, ranging from bacteria such as H. pylori (Rain et al., 2001) to human (Stelzl et al., 2005), covering unicellular eukaryotes such as yeast (Gavin et al., 2002; Ito et al., 2000; Uetz et al., 2000) or multicelular organisms such as C. elegans (Li et al., 2004) and D. melanogaster (Giot et al., 2003). These interactomes, in spite of having provided a lot of information on living systems (Uetz and Finley, 2005), still have a high degree of error (von Mering et al., 2002; Aloy and Russell, 2002b) and their determination is very expensive in terms of time and money (see the section “Future Trends”).

Computational Methods Based on Genomic Information

In parallel to these experimental approaches for the detection of interacting pairs of proteins, a number of bioinformatics techniques have also been developed. These methods, based on genomic and sequence features intuitively related with protein interaction, usually detect pairs of proteins that may interact physically or functionally (i.e., proteins that form part of the same signaling or metabolic pathway).

The results of many of these methods can be accessed online at repositories such as STRING (von Mering et al., 2003) (http://string.embl.de). These data can be used for inferring the functional role of a protein by identifying its potential interactors. This is called “context-based” function prediction and is orthogonal and complementary to the classic sequence-based functional transfer.

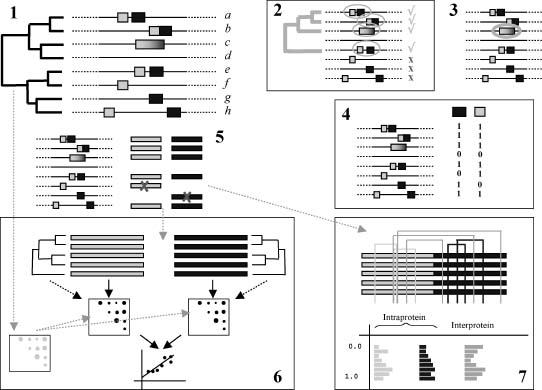

The main methods based on sequence and genomic features for predicting interacting pairs of proteins are depicted in Figure 26.4.

Phylogenetic Profiling. This method is based on the detection of pairs of genes that have a similar species distribution. That is, they are present/absent in the same species (Pellegrini et al., 1999). The idea behind this approach is that proteins that need each other to perform a given function will either be simultaneously present or absent. In the second case, loss of interacting partners can be observed as a consequence of “reductive evolution” where the organism (especially bacteria) would eliminate genes when the corresponding interacting partner is not present. As a result, interacting or functionally related genes would tend to have similar phylogenetic profiles, that is, similar patters of presence/absence (Figure 26.4, panel 4).

In their first versions, phylogenetic profiles were coded as binary vectors with “1” coding for the presence of a given gene and “0” coding for its absence (Figure 26.4, panel 4). Later, quantitative information was incorporated by encoding the similarity of a protein sequence in a given organism with respect to an organism of reference into the positions of the vector, representing in this way not only the presences/absences of the genes but their relative divergences as well (Date and Marcotte, 2003). Another improvement came from the incorporation of information on the phylogeny of the species involved, together with an evolutionary model of gene gain and loss. This allows to naturally exclude profile similarities not due to functional reasons but rather to the underlying evolutionary (Zhou et al., 2006; Barker, Meade, and Pagel, 2007).

Not only are similar profiles informative but also the “anticorrelated” ones (one protein is present whenever the other is absent and the other way around). These anticorrelated profiles have been related with enzyme “displacement” in metabolic pathways (Morett et al., 2003). Furthermore, this versatile technique has recently been extended to triplets of proteins, allowing the search for more complicated patterns of presence/absence (e.g., “protein C is present if A is absent and B is also absent”), which allows the detection of interesting cases representing biological phenomena beyond binary functional interactions, like complementation (Bowers et al., 2004).

This successful approach has two main limitations. First, it cannot be applied to many essential proteins, since they are present in all organisms and hence they create noninformative profiles. Second, this methodology requires fully sequenced genomes in order to accurately determine whether a given gene is present in an organism or not.

Conservation of Gene Neighboring. The conservation of the proximity of genes along the genome between distantly related species to predict interaction is also being utilized by several methods (Dandekar et al., 1998; Overbeek et al., 1999). A typical example would be proteins encoded by genes within a conserved operon where, if present together in another bacteria, would contain the sufficient, necessary components to execute the functional mechanism related with the activity of that operon.

Figure 26.4. Theme of strategies implemented in computational methods for assessing the possible interaction between two proteins. (1) Sequence and genomic information about two proteins (yellow and blue) is used to assess their possible interaction. The inputs for these methods are the sequences and genomic positions of the orthologs of the two proteins, as defined by a given orthology criteria, in a number of organisms (related by a phylogeny). (2) Conservation of gene neighboring: the number of genomes where both proteins are close (according with a given distance cutoff) and their phylogeny are used to assess whether the proteins are interacting or not. (3) Gene fusion: a search for genomes where both proteins appear as part of a single polypeptide is performed. (4) Phylogenetic profiling: phylogenetic profiles for both proteins are constructed by assessing the presence [1] or absence [0] of the two proteins in the set of genomes, and the similarity between these profiles is evaluated. (5) Multiple sequence alignments for the two proteins are built using the sequences of the organisms where both are present. These MSA are used by the following two methods. (6) Similarity of phylogenetic trees: the multiple sequence alignments ofthe proteins (5) are used to generate distance matrices for both sets of orthologs. Alternatively, these multiple sequence alignments can be used to generate the actual phylogenetic trees and extract the distance matrices from them. The similarity of these distance matrices is used as an indicator of interaction. Eventually, the phylogenetic distances between the species involved can be incorporated in the method for correcting the background similarity expected between the trees due to the underlying speciation events. (7) Correlated mutation: the accumulation of correlated mutations between the two multiple sequence alignments is used as an indicator of interaction. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

The limitation of this technique is that this approach is reserved for bacterial genomes where there is a clear tendency for the clustering of functionally related genes in operons to allow cotranscription. Inferences can only be made for eukaryotic proteins only if homologues are clearly established in a prokaryotic organism.

Gene Fusion. A third group of methods is related to the presence of fused genes in various genomes (Enright et al., 1999; Marcotte et al., 1999). This strategy uses the observation that some interacting protein pairs are encoded by two independent genes in some organisms whereas they are encoded by a single gene in other organisms. In such cases, it will be logical to conclude that the two proteins, as independent entities or as domains of the same protein, would be functionally related.

Marcotte et al. (1999) proposed an evolutionary hypothesis for explaining such fusion events: if two proteins have to interact in order to perform a given function, the concentration of the active complex would be much higher if the two proteins are fused together than if the two proteins are separated and hence having to rely on random diffusion to find each other and form the active complex.

The fact that two proteins are fused is a clear indication of their functional relationship (except for “promiscuous domains”). Hence, this approach produces almost no false positives. The disadvantage, however, is the range of applicability because these fusion events, in spite of being very informative, are not very frequent.

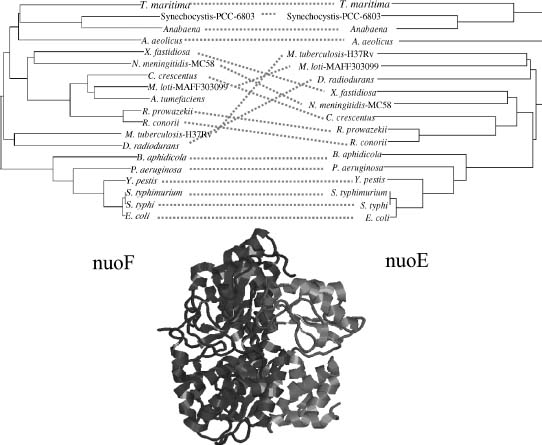

Similarity of Phylogenetic Trees. The observation that interacting proteins tend to have topologically similar phylogenetic trees has been used by some methods to predict interaction partners. This similarity was qualitatively observed in sporadic examples of interacting families such as insulin and insulin receptors (Fryxell, 1996), and first quantified for two proteins by Goh et al. (2000). Pazos and Valencia (2001) statistically demonstrated the relation between the similarity of phylogenetic trees and interaction in large sets of interacting proteins. Figure 26.5 shows an example of two interacting proteins (the nuoE and nuoF subunits of the NADH dehydrogenase complex) that have similar phylogenetic trees.

The hypothesis behind this approach is that interacting proteins would be subject to a process of coevolution that would be translated into a stronger than expected similarity between their phylogenetic trees (Juan et al., 2008a; Pazos and Valencia, 2008). The first generation algorithms of this approach measure similarity between the phylogenetic trees by indirectly evaluating it as the similarity between the distance matrices of the two families, using a correlation formulation (Pazos and Valencia, 2001).

Since it was proposed, this simple and intuitive method (mirrortree) has been applied to many proteins, and different implementations and variations of it were developed (Juan et al., 2008a; Pazos and Valencia, 2008). For example, this concept of similarity of trees was used to look for the correct mapping between two families of interacting proteins (e.g., to select which ligand within a family interacts with which receptor within another family). The idea is that the correct mapping (set of relationships between the leaves of both trees) will be the one maximizing the similarity between both trees (Ramani and Marcotte, 2003; Izarzugaza et al., 2006). Another obvious extension of the method has been to incorporate information on the phylogeny of the species involved in the trees in order to correct the “background” similarity expected between any pair of trees due to the underlying speciation process (Pazos et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2005). Recently, it has also been shown that incorporating information on the whole network of interprotein co-evolutions drastically improves the accuracy of this methodology (Juan et al., 2008b).

Figure 26.5. Example of two interacting proteins that have similar phylogenetic trees. The E. coli proteins are the nuoE (gray) and nuoF (black) subunits of the N module of the NADH reductase. The structure corresponds to the T. thermophilus orthologs (chains B and A in PDB 2FUG). The phylogenetic trees of these two proteins are shown at the top. The species correspondence is indicated with dotted lines.

One important limitation of this method is that it can only be applied to pairs of proteins where the orthologs are found in many common species. Only the leaves of the trees corresponding to species where both proteins are present can be used (Figure 26.4, panel 6).

Other Sequence-Based Methods. There are a number of other methods for inferring protein interactions from genomic information.

Coevolving positions (see the section “Coevolving Positions”) have been used for predicting interacting pairs of proteins (Pazos and Valencia, 2002), extending their previous usage for detecting interacting surfaces (see the section “Methods based on Multiple Sequence Alignments”). The idea is that pairs of multiple sequence alignments corresponding to interacting proteins would be more enriched in interprotein correlated mutations than pairs that do not interact.

The methods described so far do not involve training, that is, they do not “learn” from examples of known interactions and noninteractions. On the contrary, there are other methods that are trained with examples (Sprinzak and Margalit, 2001; Jansen et al., 2003; Yamanishi, Vert, and Kanehisa, 2004; Ben-Hur and Noble, 2005; Chen and Liu, 2005). In general, the input is a set of characteristics (descriptors) of the proteins or protein pairs (including experimental data in some cases). Based on a set of known interactions, amachine learning classifier “learns” to distinguish interacting from noninteracting pairs using the values of these descriptors. For example, Sprinzak and Margalit (2001) use pairs of sequence signatures extracted from known interactions to predict new ones. One of the descriptors used by some of these methods is the domain composition of the proteins (Bornberg-Bauer et al., 2005; Chen and Liu, 2005). The idea is that some combinations of domains are more prone to interact.

Computational Methods Based on Structural Information

There are also computational methods for the prediction of interaction partners that use structural information. Most of these methods are intended to predict whether the homologues of two proteins known to interact will interact too or not. Aloy et al. derived statistical potentials from known interactions and then used them to score the possible interactions between the homologues of the members of a given complex (Aloy and Russell, 2002a; Aloy and Russell, 2003). In a similar way, the energetic feasibility of different complexes between members of the Ras family and different families of Ras effectors was evaluated using the FOLD-X program (Kiel et al., 2007).

FUTURE TRENDS

Deciphering the complex network of protein interactions behind cellular processes is crucial for understanding many aspects of living systems and is being tackled with ongoing experimental and computational techniques in need of further developments. Currently, the experimental techniques for the massive characterization of these networks still have several important drawbacks. First, there is a surprisingly low overlap between the results of similar experiments (Uetz and Finley, 2005). Second, experimental techniques such as yeast two hybrid often yield a large number of false positives with an accuracy estimated to be as low as ~ 10% in some cases (von Mering et al., 2002). Third, experimental approaches are still far from reaching a “high-throughput” state since the intrinsic drawbacks of the methodologies allow them to test a fraction of all possible pairs of proteins (Uetz and Finley, 2005). Finally, other limitations of these techniques paradoxically arise from their experimental nature. These include the tendency to preferentially detect interactions between highly expressed proteins or between proteins belonging to a particular cellular compartment in detriment of others (von Mering et al., 2002).

Computational methods, while having their own set of limitations, are free from many of these drawbacks faced by experimental approaches. Thus, these two classes of methods complement each other. A common limitation of the computational methods for detecting interaction partners is the dependency on the quantity and quality of the genomic data. For this reason, we expect the accuracy of these methods to improve as more sequences and genomes become available. The use of structural information can help improving the performance of current methodologies. For example, HMM derived from structural alignments (Chapters 16 and 22) are widely used for detecting remote homologues. The localization of homologues is common to many of these computational techniques.

We are already seeing a combination of results from the new experimental powerful techniques, the new bioinformatics approaches for the prediction of interacting partners, the relations established between genes with similar expression patterns in DNA array experiments, and the systematic mining of available information about protein interactions in databases and literature repositories (Hoffmann and Valencia, 2004). Combining and finding consensus within these accumulated information obtained from different sources, we will quickly approach a situation in which it will be possible to glimpse the structure of the complex network of protein interactions that govern cell life in relatively simple model systems such as yeast and bacteria.

The methods for predicting interaction partners and detecting interacting regions are helping in the interpretation of the massive amounts of sequence and genomic information in functional terms. The promise is that the combination of improved experimental techniques and computational methods along with an effective consensus interpretation of accumulated data from widely disparate sources would lead not only to a better understanding of cell function but also to better ways of manipulating it with new and more specialized drugs designed specifically for that purpose.