27

DOCKING METHODS, LIGAND DESIGN, AND VALIDATING DATA SETS IN THE STRUCTURAL GENOMICS ERA

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of civilization, humans have searched for substances that can cure or alleviate the symptoms of disease. In the early stages, extracts from plants and animal parts were used to treat disease, and the discovery of such remedies was driven empirically. Starting in the early 1900s, drug discovery has increasingly focused on discovering and developing chemical entities that on their own have a desired pharmaceutical effect. Initially this was fueled by attempts to extract and identify the active component in extracts from natural products that were used. A number of developments, however, have resulted in the multidisciplinary science that drug discovery is today, including the traditional fields of chemistry and pharmacology, along with contributions from biochemistry, molecular biology, and biophysics. Increasingly, computational tools are used in the drug discovery process from target identification and validation to the designing of new molecules.

The discoveries of several different concepts played a pivotal role in the development of drug discovery as an industry. In the nineteenth century, Paul Ehrlich developed the idea that different parasites, microorganisms, and cancer cells have dissimilar chemoreceptors resulting in different susceptibility to dyes. He hypothesized that these differences can be exploited therapeutically (Ehrlich, 1957). In 1905, Langley expanded the concept of receptors to being binding sites for different substances. Binding of the substrate to the binding site can result in either stimulation or blocking of the receptor depending on the substance used (Langley, 1905).

Emil Fisher developed the “lock-and-key” concept for enzymes, which stipulates that the substrate has to fit exactly into the binding site for the enzyme to perform its function on the substrate (Fischer, 1894). Koshland put a slightly more flexible point of view forward in the “induced-fit” model that states that both ligand and enzyme undergo conformational changes to fit optimally (Koshland, 1958). More recently, Foote and Milstein put forward the idea that optimally fitting conformers of both receptor and ligand exist in solution, and that in the presence of each other, there is a shift in the equilibrium toward the best-fitting conformers for both, resulting in binding (Foote and Milstein, 1994).

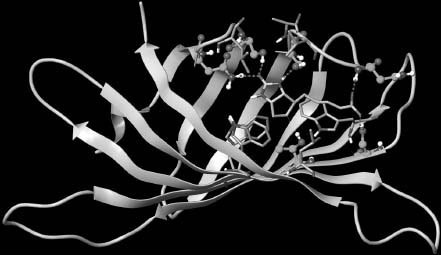

The field of structure-based drug design (Chapter 34) most explicitly exploits the concept of three-dimensional binding sites that interact with ligands; computational methods and models play herein a critical role (Figure 27.1). In structure-based design, the known or predicted shape of the binding site is used to optimize the ligand to best fit the receptor. The driving forces of these specific interactions in biological systems are driven by complementarities in both shape and electrostatics of the binding site surfaces and the ligand or substrate. Van der Waals interactions thus play a role, in addition to Coulombic interactions and the formation of hydrogen bonds (Figure 27.2). Docking is one of the tools used to understand and explore the steric and electrostatic complementarity between the receptor and the ligand.

The interactions between the receptor and ligand are quantum mechanical in nature, but due to the complexity of biological systems, quantum theory cannot be applied directly. Consequently, most methods used in docking and computational drug discovery are more empirical in nature and usually lack generality. Quantum mechanical phenomena, such as the formation of a covalent bond between the protein and the ligand upon binding during the transition state of the reaction, cannot be predicted and/or evaluated using these empirical methods.

Figure 27.1. Structure-based drug discovery cycle. Either an X-ray structure or a homology model can be used for binding mode predictions of known leads and virtual screening to find new leads. The known or predicted binding mode of leads can be used to design analogues with better and more interactions with the protein. Prioritized analogues have to be synthesized, experimentally tested, and the structure–activity relationships obtained can be used to further optimize the ligands.

Figure 27.2. Streptavidin bound to biotin. Picture highlighting interactions between streptavidin (orange carbon atoms) and biotin. Amino acid residues that interact through hydrogen bonds with the ligand are shown with cyan-colored carbons, residues providing hydrophobic interactions have gray carbons. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

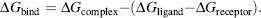

The strength of the interaction between the ligand and the receptor can be measured experimentally and is often reported as the dissociation constant, Kd, or by the concentration of ligand that inhibits activity by 50%, the IC50. The binding free energy is the thermodynamic quantity that is of interest in computational structure-based design and is defined by Eq. 27.1:

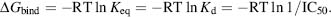

The relationship between the binding free energy ΔG and the experimentally determined Kd or IC50 is shown in Eq. 27.2:

With Eq. 27.2, it is possible to calculate the binding free energy where the Kd is defined with respect to the standard state (Atkins, 1997), and measurements done in different laboratories can only be compared when performed under the same standard state, that is, experimental conditions. The pressure, 1 atm, and the activity of the solutions, namely 1 M, define standard state conditions.

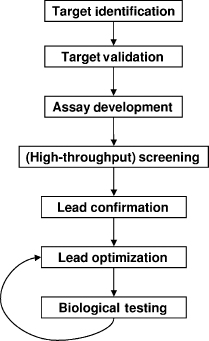

Modern drug discovery cycle usually starts with the identification of a biological target (Figure 27.3), most often a protein, known to play a critical role in a particular disease. Biological assays are developed that can measure inhibition (or activation) of the target of interest by small molecules in vitro or in vivo. If amenable to high-throughput screening, pharmaceutical companies usually screen their entire corporate collection of molecules in the assay against the target to identify possible leads. Often several hundred thousand molecules are tested in the high-throughput screening (HTS). During HTS each compound is generally tested once at a single dose yielding a percent inhibition value. Numerous hits are identified, based on statistical significance of the measured percent inhibition, and confirmed in subsequent assays. Follow-up tests include dose-response assays and confirmation that the compounds inhibit the target by a specific mechanism rather than through nonspecific binding (McGovern et al., 2003). The HTS liquid samples of the hits are also tested on purity and integrity to ensure that the measured activity is due to the structure assumed to be in the sample. As the number of hits gets smaller, similarity searches will usually be performed and similar structures will be tested for activity. Analogue testing is a way to develop structure-activity relationships (SAR) early on and further validate the hits. The hits are narrowed to a limited number of different chemical lead series (usually <10) that will be explored by making chemical modifications. As the project continues, the number of lead series that is investigated becomes smaller and more analogues are made for potential leads to further SAR investigations. In addition to optimization of potency, physical-chemical properties that influence absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME) properties, and toxicity are also modulated. Eventually, of the hundreds of thousands of molecules tested and thousands of molecules synthesized, one molecule might make it into clinical trials and perhaps become an FDA-approved drug.

Figure 27.3. Moderndrug discovery cycle.Moderndrug discovery starts with identifying potential targets that play a role in disease. The target has to be validated, for example through gene-chip analyses, siRNA experiments, gene knockout experiments, and so on. Once the target has been validated, a biological assay has to be developed that can be used to identify potential leads. After lead identification through screening, hits are confirmed by reassaying, IC50 and Kd determinations, NMR experiments that measure protein binding of the hits, analogue testing, and so on. Once hits have been confirmed, analogues are synthesized to further optimize the lead series for potency and ADME/Tox properties.

The receptor-based drug design cycle starts with the availability of a crystal structure or homology model of the target of interest (Figure 27.1). Similarly to HTS, a virtual screen (VS) is usually performed to identify molecules that are compatible with the active site of the target. Just as in HTS, hundreds of thousands, and even over a million, compounds can be screened with current hardware and software. Top-scoring hits are tested in a biological assay to determine activity and confirmed hits from both VS and HTS can be optimized based on the predicted binding modes and ideal protein-ligand complex structures. Numerous cycles of optimization are applied to these series of leads.

In this chapter, we discuss the basis of docking algorithms and focus on their use, along with other approaches, in structure-based drug design that has served as one of the main driving forces to improve docking models. We also cover strategies to identify binding sites and protein targets that are important for rational small molecule and fragment-based drug design. With the increasing availability of crystal structures of receptors that are pharmacologically important, with or without ligands bound, numerous analyses have been performed to extract reoccurring patterns. Consequently, new methods and tools taking on a more heuristic, bioinformatics approach have been developed to take advantage of these data in an aggregate fashion which are complementary to docking algorithms.

DOCKING AND SCORING

Docking can be used to predict how a ligand interacts with the binding site of a receptor (Figure 27.2). The ligand is usually a small molecule, but can be a protein as well. The receptor is most often a protein of pharmacological interest, but can be a particular sequence of DNA or RNA as well. The prediction of the protein-ligand complex is usually done by searching the translational and rotational degrees of freedom of the ligand within the receptor binding site, and by searching the conformational degrees of freedom of the ligand itself. Binding conformations generated by docking programs are thus defined by both a position of the ligand on the receptor surface and a particular ligand conformer. The first docking algorithm for small molecules was developed by the Kuntz group at UCSF in 1982 (Kuntz et al., 1982). Subsequent application of this program to find new leads against HIV-1 protease highlighted the potential of using computer-based screening in drug discovery (DesJarlais et al., 1990). Since then, many different docking algorithms have been developed, and structure-based drug design has become a standard tool in drug discovery.

Before ligands can be docked against a receptor, generally the binding site has to be identified first. This is done to limit the search space on the receptor surface and thus minimize the degrees of freedom that have to be searched. The active site is often known from crystal structures of ligand-bound receptors, but it can also be predicted. The largest cavity on a protein surface is frequently the active site, but this is not always the case and different active site prediction and analysis methods have been developed.

The basis for the DOCK search algorithm can be found in distance geometry and consists of sets of ligand atoms that are being matched to sets of receptor spheres. The receptor spheres describe the binding site and can be viewed as a ’’negative image’’ of the active site and thus match what the ideal ligand shape would look like. The matching of ligand atoms to receptor spheres is used to search the translational and rotational degrees of freedom of a rigid ligand in the active site (Kuntz et al., 1982).

The second part of a docking program consists of a scoring function, which will distinguish among the generated binding modes the best solution that closely matches the actual mode of binding. The most-favorable predicted protein-ligand complex is considered to be the biologically relevant one. A large number of different search algorithms and scoring functions have been developed to model protein-ligand docking and are discussed in this section. The various applications of docking, namely binding mode prediction and virtual screening, are also discussed. While the receptor is often considered to be rigid in docking experiments, this is not realistic for the binding sites are flexible. Different approaches that incorporate limited receptor flexibility will also be highlighted.

Search Algorithms

Docking algorithms generally contain two search engines, one is responsible for the placement and exploration of the ligand in the binding site, while the other searches the internal degrees of freedom of the ligand, that is, angles and dihedral angles. Some docking programs only dock rigid ligands and use pregenerated ligand conformers, this approach serves to conserve computational resources but may not necessarily provide the best solution. Pregenerated ligand conformers can be generated with some of the following methods: OMEGA (OpenEye Scientific Software; Verdonket al., 2003a), Corina (Gasteiger, Rudolph, and Sadowski, 1990), MacroModel (Schrodinger Inc.), and Concord and Conform (Tripos Discovery Informatics).

For ligands without any degrees of freedom, it is feasible to search the six translational and rotational degrees of freedom in the receptor binding site (or even the full receptor surface). However, as the number of rotatable bonds of the ligand increases, the number of degrees of freedom increases exponentially when finding solutions to fit into the binding site. Search algorithms try to find a balance between searching the energy landscape as thoroughly as possible, while still finding a solution within a reasonable amount of time.

Several different orientation algorithms are available and can be divided into three major categories. The first method is a grid search that exhaustively searches the binding site by moving the rigid ligand through the available 6 degrees of freedom in a systematic fashion in the binding site. Search time and accuracy are determined by the size of the three-dimensional grid and the size of the steps that are taken. Fast Fourier transform (FFT) methods have been applied to speed up the search. FFT performs the search in Fourier rather than Cartesian space, which leads to significant enhancements of speed. The original algorithm only looked for surface complementarity (Katchalski-Katzir et al., 1992), but later implementations also use electrostatic complementarity, as in FTDOCK (Gabb, Jackson, and Sternberg, 1997) for example. Unfortunately, because most ligands are flexible, the number of degrees of freedom to be searched with a grid search is too large, and this approach is not used in small-molecule docking algorithms. However, it is applied in protein-protein docking algorithms, which generally treat both proteins as rigid molecules.

The second and significantly more efficient algorithm places ligands in the binding site by descriptor matching (Ewing and Kuntz, 1997). Descriptors to find a solution are generally points, sometimes with properties associated to them, placed in the receptor site. Ligand atoms are matched with the receptor descriptors with some tolerance. The descriptor-matching algorithm orients the ligand in the binding pocket, which subsequently has to be optimized and scored. Usually a large number of orientations are possible, and they all have to be explored and optimized. Careful pruning of the search tree is necessary to ensure efficiency and avoid an exponential growth of the systematic search (Ewing et al., 2001; Moustakas et al., 2006b). When binding site descriptors are associated with physical-chemical properties, such as hydrophobicity and hydrogen-bonding capabilities, the ligand atoms have to match geometrically as well as chemically. DOCK (Shoichet and Kuntz, 1993; Moustakas et al., 2006b), FlexX (Rarey, Wefing, and Lengauer, 1996) and PhDOCK (Joseph-McCarthy et al., 2003) use descriptor matching to orient the ligand in the binding site. Usually sets of three or four receptor spheres, minimally, are matched to the same number of atoms in the ligand. If the intersphere distances are similar to the interatom distances a match has occurred and the ligand can be placed in the binding site.

In the third class of algorithms are energy-based search methods using molecular mechanics force fields (Table 27.1) to explore the energy surface of the ligand with molecular dynamics (MD) or energy minimization algorithms. The minima of the ligand on the surface have to be located and assessed in terms of their complementarity to the receptor. Energy minimization is a local search, and is only used to optimize binding conformations generated by other search engines. MD searches are global searches in principle, but also tend to get stuck in local minima. Consequently, simulation search times have to be long to ensure full coverage of the binding site and, consequently, limits their applicability as a high-throughput solution to computationally identify binding targets (David, Luo, and Gilson, 2001). Some alternatives to help speed up the search time include genetic algorithms, as implemented in AutoDock (Morris et al., 1998) or GOLD (Jones, Willett, and Glen, 1995), and Monte Carlo searches (QXP; McMartin and Bohacek, 1997) which are stochastic and help prevent simulations from being stuck in a local minima when searching for solutions. This search strategy generally explores all degrees of freedom simultaneously, and is therefore not strictly considered as orientation algorithms.

Molecules that contain rotatable bonds can occupy different conformers in solution, but usually occupy a single conformer when bound to the protein. Different conformers of a ligand have different internal energies. The internal energies of the ligand and the protein are generally ignored during the search for the most optimal ligand pose in the binding site, but docking algorithms do eliminate physically unrealistic conformers for the ligand, for example, conformers with overlapping atoms.

In summary, the presence of rotatable bonds in the ligand increases the degrees of freedom that have to be explored as well. Ligand search algorithms can be divided into three types of methods, namely systematic, stochastic, and deterministic. Molecular dynamics and energy minimization are deterministic, and genetic algorithms and Monte Carlo searches (see above) are stochastic search algorithms. As described for the grid search, a systematic search for all degrees of freedom and different ligand orientations in the binding site would be too time consuming. One can limit the degrees of freedom to be searched by docking a rigid part of the ligand first, the so-called anchor, and incrementally adding the bonds one at a time (’’grow’’). The ’’anchor-and-grow’’ algorithm has been implemented in a number of docking programs, namely DOCK (Ewing and Kuntz, 1997) and FlexX (Kramer, Rarey, and Lengauer, 1999). The anchor-and-grow algorithms are not guaranteed to be exhaustive.

Ligand flexibility can also be dealt with by rigidly docking pregenerated conformer libraries. Especially for large compound libraries used in virtual screening, this is a very efficient method for handling ligand degrees of freedom. The cost of generating the conformers has to be only incurred once, and the library can subsequently be docked quickly against any target of interest. The Shoichet laboratory implemented this strategy in the DOCK algorithm (Lorber and Shoichet, 1998), and pregenerated conformer libraries are also used in PhDOCK (Joseph-McCarthy et al., 2003) and EUDOC (Pang et al., 2001a). Key to successful convergence on a solution is that the generated conformer ensemble for each ligand contains a conformer that is close, probably <1Å(1Å = 1 x 10-10m) RMSD (root mean square deviation) to the actual solution. Usually the bioactive conformer is not the conformation found at the global energy minimum in the energetic landscape. Therefore it is necessary to generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers that will hopefully contain a conformer that is close enough to the bioactive conformer and will dock in the correct binding mode. As mentioned earlier, different conformer generation algorithms are available to efficiently generate low-energy conformers for ligands. A number of studies have investigated the ability of these algorithms to dentify bioactive conformers. As expected, the chances of retrieving a biologically active conformer decrease as the number of rotatable bonds increases. However, for lead-like ligands (see the section ’’Ligand-Based Perspectives’’) with less than eight rotatable bonds, a conformer within 1 Å of the bioactive conformer can be found in >80% of the cases. Macromodel was shown to have the best success, but at a much more significant computational cost than rule-based OMEGA (Bostroem, 2001; Good and Cheney, 2003).

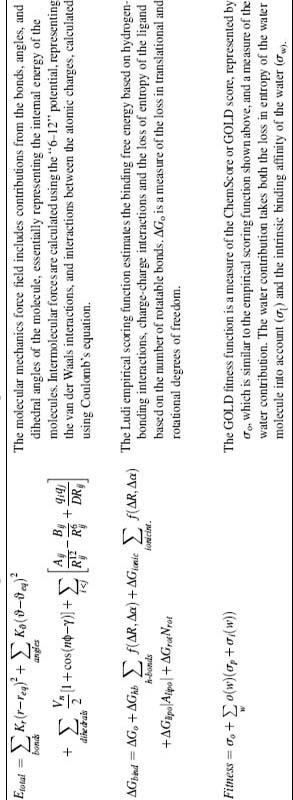

TABLE 27.1. Different Scoring Functions Used for Docking

Some weaknesses with docking approaches need to be considered when applying these algorithms to find optimal docking solutions. A recent study by the Vertex group highlighted that the bioactive conformer of a ligand is rarely found in the low-energy conformer. A large-scale study was performed using 150 protein-ligand complexes of pharmaceutical interest, with available IC50 and/or Kd measurements. Several different methods were used to generate the global minimum conformation of each ligand in solution. The strain energy for each ligand was calculated using the partially minimized crystallographic conformer and the global minimum energy of the ligand. As expected, the majority of the ligands do not bind to the receptor in the global-minimum conformation. Somewhat surprisingly, however, was the observation that 60% of the ligands do not bind in a local energy conformation either. As a consequence, ligand strain energies are quite high and can even exceed 9 kcal/mol (Perola and Charifson, 2004).

Furthermore, observations by Perola and Charifson showed that interaction energies estimated, without taking into account the internal ligand energy, are off with an error of 0-10 kcal/mol. Tirado-Rives and Jorgensen have calculated the cost of ’’conformer focusing’’ upon protein-ligand binding using both force field and quantum mechanical calculations. With the accuracy of current force fields, even inclusion of the ligand strain energy results in an uncertainty in the binding free energy calculation of between 5 and 10 kcal/mol. Thus, to accurately obtain free energies of binding, more accurate force fields are required (Tirado-Rives and Jorgensen, 2006). Their study also highlights that using a constant penalty per rotatable bond is not correct.

Scoring Functions

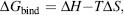

As mentioned earlier, we are interested in the binding free energy ΔGbind of the ligand with the protein. ΔGbind is a function of both enthalpic and entropic energies as in Eq. 27.3:

where ΔH , enthalpy, is a result of the changes in van der Waals and Coulombic interactions as water is removed from the binding site and the ligand surface and replaced with van der Waals and Coulombic interactions between the receptor and the ligand. Changes in internal energy of the receptor and the ligand have to be considered also. Entropic changes ΔS upon binding are a result of restricting the internal degrees of freedom of the receptor, especially in the binding site, and the ligand, as well as changes in translational and rotational degrees of freedom. The loss of flexibility and other entropic changes are generally unfavorable to complex formation. Another large contributor to the entropy is the solvent, which generally gains entropy as it is released from the protein binding site, and the ligand upon complex formation. This so-called ’’hydrophobic effect’’ (Kauzmann, 1959) is often the driving force for protein-ligand interactions. The binding free energy is thus a complex term, which can be calculated directly, but at a considerable computational cost (Head, Given, and Gilson, 1997; Woo and Roux, 2005). Because of the complex nature of binding free energies, the quest for generally applicable and highly accurate scoring functions that can be evaluated quickly is still on going.

Relative binding free energies can be calculated more easily, and is applied more frequently in drug discovery. The methods used are either thermodynamic integration (TI) or free energy perturbation (FEP) (Kollman, 1993), and the relative binding free energy is obtained by slowly ’’mutating’’ one ligand into another one. This is generally only feasible for small changes to the ligand. One thus only obtains the energy difference between a ligand and a close analogue. In lead optimization, this can be used to prioritize what molecule to synthesize next from a pool of possible ligands to make. However, even calculation of relative binding free energies still comes at a considerable cost. Part of the reason FEP/TI calculations are time consuming is that (unphysical) intermediate states have to be sampled extensively in going from one ligand to its analogue.

More practical approaches to calculating binding free energies can be divided into four major approaches: first-principles scoring functions, semiempirical methods, empirical scoring functions, and knowledge-based potentials. First-principles methods generally use a molecular mechanics force field (Table 27.1), although often the intramolecular forces between the atoms are not calculated to save time. Since the molecular mechanics force field only accounts for enthalpic forces between the protein and the ligand, the estimated binding free energy is only an approximation to the true binding free energy. DOCK (Meng, Shoichet, and Kuntz, 1992) and the original AutoDock (Goodsell and Olson, 1990) use molecular mechanics scoring functions. With the rigid receptor assumption, the energies contributed by the receptor can be precalculated and stored on a grid. This significantly speeds up the calculations and makes use of a molecular mechanics scoring function in docking feasible. Interactions with solvent are generally not accounted for.

A commonly observed phenomenon is the high ranking of charged ligands due to an overestimation of charge-charge interactions to the binding free energy in energy-based scoring functions. A newer strategy uses a tiered approach to score and post-process the generated binding conformations to estimate the contribution of the solvent with a continuum solvent model such as the Poisson-Boltzmann (Warwicker and Watson, 1982; Gilson and Honig, 1988) or Generalized Born (Bashford and Case, 2000) methods. These enhanced scoring functions generally show better agreement with true binding free energies (as measured by the Kd/IC50) and improved rank ordering of compounds (Shoichet, Leach and Kuntz, 1999; Zou, Sun, and Kuntz, 1999; Lyne et al., 2004;Huang et al., 2006). At this point, it is not feasible to include the continuum solvent models directly into the docking calculation.

The linear interaction energy (LIE) method (Aqvist, Medina, and Samuelsson, 1994) is a semiempirical method that was developed to calculate absolute binding free energies while avoiding the need for the extensive sampling of nonphysical transition states as in FEP or TI. Due to its semiempirical nature, the parameters are not generally applicable and need to be derived for every new target and/or new chemical series. This requires the availability of reliable binding data. Although only the initial and final states are simulated with either molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations, the method is still time-consuming and is only used in lead optimization and not in lead identification (Ljungberg et al., 2001; Rizzo, Tirado-Rives, and Jorgensen, 2001).

Numerous empirical scoring functions have been developed (Table 27.1), and a significant advantage is that they can be evaluated rapidly and thus can be used in high-throughput applications such as docking. An empirical scoring function consists of a number of terms known to play a role in protein-ligand complex formation such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts between the protein and the ligand. The weights for each of the terms are derived by fitting the equation using regression methods to a training set of protein-ligand complexes for which both structural information and experimentally determined interaction energies are known. While the terms used represent the physical principles underlying complex formation, there are several weaknesses to consider. First, due to the fitting, much of the atomic detail is lost. Second, the scarce sampling of the chemical space limited by available protein-ligand complexes with reliable measured IC50 or Kd values results in empirical scoring functions that are general rather than specific (Tame, 1999). Third, most empirical scoring functions consider interactions by simply looking at the distances and angles (in the case of hydrogen bonds) of the atoms that are involved. However, it is quite likely that the environment in which the interaction occurs plays arole also. To address these limitations, the program Glide now has a new scoring function that accounts for the environment of hydrogen bonding interactions and therefore differences in contributions from different hydrogen bonds are more properly modeled (discussed later; Friesner et al., 2006).

Based on work done in the protein folding community (Sippl, 1990), knowledge-based potentials have been developed to score protein-ligand interactions (Mooij and Verdonk, 2005; Muegge, 2006). Knowledge-based functions are derived using protein-ligand complexes alone, based on the statistical assumption that interactions that are more frequently observed are more important for complex stability. This is the basic assumption in statistical mechanics and the Boltzmann principle. The advantage of this approach over the derivation of empirical scoring functions is that more protein-ligand complexes can be used for deriving potentials since the prerequisite for experimentally determined IC50/Kd for each complex has been eliminated. This approach is more computationally efficient, less time demanding, and therefore can be used in docking programs.

Water molecules play a critical role in the formation of protein-ligand interactions and are a significant determinant in the binding free energy. One approach to account for solvent effects is by using a continuum solvent model. While this is improvement over accounting only for direct protein-ligand interactions, in many cases it is not enough. The continuum solvent models do not account for two explicit water molecule contributions. First, some water molecules serve to bridge interactions through hydrogen bonding between the ligand and protein and therefore affect the binding affinity. Second, some well-defined water molecules can be displaced by the ligand and significantly contributes to the binding affinity due to the increase in translational and rotational entropy upon release. With the improved computational power, more realistic scoring functions have been implemented in recent years to account for the role of water molecules in more detail.

FlexX is an example of an algorithm that accounts for contributions from water molecules using a particle approach. In the first step, phantom particles are generated using the protein structure of the active site; Particles with more than two interactions with the protein are retained. The second step, ligand docking, involves turning ’’on’’ and ’’off’’ the phantom particles to determine if interactions are formed with the ligand. Particles interacting with the ligand are then used in the scoring function to determine ligand binding capacity (Rarey, Kramer, and Lengauer, 1999). The energy change associated with the release of waters from the active site is not accounted for explicitly with this approach.

GOLD is another algorithm with scoring functions that accounts for the contribution of both bridging and displaced waters. The user specifies which water molecules are to be retained during the docking search and GOLD will further explore whether the water molecule should be included in the ligand binding process. For each water molecule, GOLD will consider the bridging potential of the water molecule, or alternatively, the displacement by the ligand. Both the Chemscore and Goldscore scoring functions (Table 27.1) have been parameterized to take both functions of water molecules into account (Verdonk et al., 2005).

Extra Precision Glide (GlideXP) has the Chemscore scoring function at its basis, but with additional terms that better incorporates the underlying physics of protein-ligand interactions. Group-based lipophilic interactions, rather than atom-based, and the protein environment in which these interactions take place is included as a term called the hydrophobic-enclosure term. Additionally, a number of other hydrogen-bonding terms have been incorporated along with pi-pi and cation-pi interactions. Accounting for desolvation, explicit waters are docked for top-scoring XP conformations and polar ligand or protein groups that are inadequately solvated will be penalized (Friesner et al., 2006).

Binding Site Identification and Mapping

Docking methods generally rely on a demarcation of the search space on the receptor surface to address the computationally intensive nature of the search problem in finding the correct ligand binding conformation. The space searched spans only the active site and requires some knowledge about the position of the binding site on the receptor. Often the active site of a receptor is known from an X-ray crystallography structure, or perhaps NMR, of a protein-ligand complex. However, sometimes the active site, or additional binding sites, has to be predicted. It is often assumed that the largest cleft on a protein surface corresponds to the active site, but this is not always the case. A number of methods are available for protein binding site predictions. The simplest methods rely on assessing structural features of the receptor alone by measuring the volumes of different cavities using alpha shapes (Liang, Edelsbrunner, and Woodward, 1998) or by placing probes on the protein surface.

DOCK adopts this strategy to reduce the sampling search space with the SPHGEN algorithm that creates docking spheres to identify potential active sites. After placement of spheres on the protein surface, these spheres can be clustered to identify the binding site, which is often defined by the largest cluster of spheres (Kuntz et al., 1982). An alternate strategy uses the physical-chemical properties of surface patches and cavities to identify active sites. For example, Jain et al. identify ’’sticky spots’’ on protein surfaces by identifying regions of the protein where different probes are predicted to have favorable interaction energies. The probes that have high interaction energies with the region define the sticky spots. The sticky spots will subsequently be extended to the largest continuous cavity possible (Ruppert, Welch, and Jain, 1997). A third strategy combines hydrophobic and hydrophilic probes with a number of additional physical parameters to identify favorable interaction sites on the protein surface as implemented in SiteMap and SiteScore. The SiteScore is defined relative to a set of 155 known tight binding sites and also serves as a measure of “drugability.” Over 95% of known binding sites in 230 proteins has been predicted correctly (Halgren, 2007).

With the ever-increasing amount of available structural information on protein-ligand complexes, the accumulating information and derived analysis can also be used to predict protein active sites. These heuristic based methods will be discussed in the section ’’Drug Design in the Structural Proteomics Era’’.

Assessing Performance of Docking Algorithms

After drug candidates have been identified with the search algorithms that have been discussed, optimization of these leads begins. For structure-based drug design to have an impact on lead optimization, the binding mode of the lead with the receptor has to be known. Docking tools play a critical role in predicting binding modes, and the ability of a docking program to correctly identify the biologically relevant binding mode from the other possibilities is the most basic test of docking algorithms.

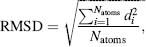

The success rate in retrieving binding modes of known protein-ligand complexes is an important validation for docking programs. The measure that is usually used to determine whether a binding mode prediction is a success is the RMSD. The RMSD is defined by Eq. 27.4 as

where di is the distance between the coordinates of atoms i in the predicted structure and the known crystal structure when overlaid. One generally considers an RMSD <2Å as a successful prediction. With larger deviations, many of the observed interactions between the protein and the ligand will not have been predicted correctly.

The current availability of protein-ligand complex structures provides opportunities to construct data sets needed for large validation studies to evaluate and improve docking methods. For flexible ligand docking, success rates of ~70% have been reported (Kramer, Rarey, and Lengauer, 1999; Panget al., 2001a; Verdonk et al., 2003b; Friesner et al., 2004a; Moustakas et al., 2006a), although it is not always predictable which program will give good predictions for a particular target and/or chemical series (Kontoyianni, McClellan, and Sokol, 2004; Warren et al., 2006b). In recent years, a number of different test sets have also appeared in the literature. The first well-curated test set was assembled by the GOLD developers which focused on crystallographic reliability (Jones et al., 1997). Recently, test sets with complexes of pharmacological interest (Perola, Walters, and Charifson, 2004), reasonable number of rotatable bonds (Moustakas et al., 2006b), and a wider diversity of representative complexes (Hartshorn et al., 2007) have been published.

The most recent CCDC/Astex set was compiled using six criteria and a final manual selection step. The six criteria are (1) date of deposition; (2) resolution; (3) availability of structure factors; (4) presence of interesting ligands; (5) drug-likeness of ligand; and (6) non-existence of overlap between protein and ligand. The manual selection process involves an assessment of the pharmacological or agrochemical interest of the ligand, presence of covalent bonds between the protein and the ligand, and the presence of incomplete side chains or missing loops near the binding site. The final set contains 85 high-quality, diverse, protein-ligand crystal structures (Hartshorn et al., 2007). The current CCDC/Astex set has no overlap with the previous one (Nissink et al., 2002).

Virtual Screening

The goal of virtual screening is to identify ligands within a large collection that can bind to the target of interest and induce the desired biological effect. The collection of compounds that is screened can be compounds in a corporate collection of a (bio)pharmaceutical company, compounds available for purchase from commercial vendors, or virtual compounds that have yet to be synthesized. In large, diverse collections of compounds, very few compounds will generally exhibit interactions with the target of interest (high-throughput screening hit rates are usually <0.5%). Screening with docking algorithms can be used to identify compounds that are most likely to show interactions with the target, thus reducing the number of compounds to be tested experimentally for activity.

In validation studies, a library of decoys is usually enriched with known inhibitors of the target from the literature. One measure of success is the hit rate, which is defined as the percentage of true hits found among the top-scoring compounds. Another measure of success is the enrichment factor (EF). The EF is defined as

(27.5)

where a is the number of active compounds among the top n compounds, and A is the total number of active compounds in the library of N compounds. Many virtual screening validation studies use decoys from commercial collections that have not been tested against the target of binding. Therefore, the EF scoring function is not reflective of the true scenario since some decoys may exhibit interactions with the target. A downside of the EF function as a measure of success is that the maximally achievable value depends on the number of active and inactive compound in the library. Similar to binding mode predictions, the EF scoring function can differ greatly from target to target for particular algorithms (Bissantz, Folkers, Rognan, 2000; Kontoyianni, McClellan, and Sokol, 2004; Warren et al., 2006a). Identifying the best program to use for the target of interest is not straightforward.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves have also been used to evaluate virtual screening experiments (Klon et al., 2004; Triballeau et al., 2005). The benefit of this approach it the independence from the ratio of actives and decoys. Additionally, it lends itself for easy interpretation with the range of values between 0 and 1, a value of 0.5 equates to random selection from the library.

Truchon and Bayly criticizes the use of ROC curves, mainly because it is not sensitive to ’’early recognition.’’ With library sizes of 500,000 compounds and more, this is an important consideration because active compounds have to rank highly to be considered for experimental screening. Usually only a few thousand compounds are screened from virtual screening, which means that active compounds have to be within the top 0.1%. The authors propose a new metric, BEDROC, to better recognize these active compounds among a large set of decoys earlier on (Truchon and Bayly, 2007).

The compilation of compound libraries can also have a significant impact on virtual screening hit rates. When the true hits have physical-chemical properties that are significantly different from the properties of the decoys, artificially high EF scores can be observed (Verdonk et al., 2004). To this end, Shoichet’s group has developed the directory of useful decoys (DUD) database, which contains 2950 actives for 40 different targets. For each active compound 36 ’’decoys’’ are chosen from the ZINC database. Decoys are similar to active compounds in terms of physical-chemical properties, but have dissimilar chemical structures. A comparison of EF scores with DUD and more biased libraries has been made, showing again that EF scores are artificially high when decoys are chosen to be dissimilar from actives (Huang, Shoichet, and Irwin, 2006).

Protein Flexibility

Although limited flexibility in the active sites are accounted for in some docking algorithms, for example FLO and GOLD (McMartin and Bohacek, 1997; Verdonk et al., 2003b), most treat proteins as rigid structures. This assumption is a seriously limitation because induced fit effects are often critical in complex formation and the crystal structure or homology model used for docking is only a single representation of the many accessible protein conformations found in solution. Minor adjustments to flexible side chains in the active site are often necessary to accommodate the ligand, which is underscored by results from ’’cross-docking’’ experiments. In cross-docking experiments, the flexible ligand is docked into areceptor crystal structure that is bound to a different ligand. Success rates in reproducing the known bound conformation of the ligand is significantly lower in cross-docking experiments than in regular docking experiments (Bissantz et al., 2000; Jain, 2003; Friesner et al., 2004b; Kontoyianni, McClellan, and Sokol, 2004; Warren et al., 2006a).

Although the need for full receptor flexibility in the active site is recognized, this is unfortunately restricted with the current computational power of available technologies. Different methods have been developed that allow for receptor flexibility while limiting the increase in computational demand. A number of groups implemented ’’ensemble’’ grids that use averaging approaches to represent a number of receptor structures (Knegtel, Kuntz, and Oshiro, 1997; Claussen et al., 2001; Oesterberg et al., 2002). The ensemble grid does not increase the computational time needed for docking the molecule, and yields significantly better cross-docking results as well as better enrichment rates (Knegtel, Kuntz, and Oshiro, 1997; Claussen et al., 2001; Oesterberg et al., 2002). Different methods have been used, including energy-weighted and geometry-weighted average grids (Knegtel, Kuntz, and Oshiro, 1997). Energy-weighted grids use a Boltzmann weighting scheme (Oesterberg et al., 2002). Another mixed representation approach merged variations in structural conformations into a single representation with dissimilar areas of the protein treated as alternatives (Claussen et al., 2001).

Several groups have explored the use of structural ensembles, usually generated from MD simulations, and docking compounds against each individual conformer (Pang et al., 2001b; Lin et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2005). The predicted binding mode is chosen based on the best-scoring protein-ligand complex. Due to inherent inaccuracies in scoring, further optimization of the generated binding modes and reevaluation of scores is sometimes needed (Wong et al., 2005). Docking time will increase linearly with the number of structures used. The use of structural ensembles in the development of pharmacophores has also been explored (Meagher, Lerner, and Carlson, 2006).

The induced fit docking (IFD) protocol combines Glide docking with the protein optimization protocols implemented in Prime. The van der Waals radii of the protein and ligand are scaled during the docking process and significant overlap is allowed in the generated protein-ligand binding conformations. These binding conformations are then optimized with a fixed ligand and the minimum energy structure of the protein is retained. Finally, the ligand is re-docked into the optimized receptor with the regular scoring function and resulting conformations are scored and ranked (Sherman et al., 2006).

DRUG DESIGN IN THE STRUCTURAL PROTEOMICS ERA

The contributions of structural genomics efforts to drug discovery based research are many. First, the increasing number of crystal structures in the PDB (Chapter 11) forms a data rich resource with protein-ligand complexes capturing the interactions formed between targets and ligands. This wealth of information has influenced the development of binding site prediction and annotation methods. Multiple structures provide a selection of choice to identify the most appropriate structure for virtual screening of compounds. Additionally, the accumulating binding data has also resulted in pilot studies to predict the selectivity of ligands for their target compared to off-targets. Feasible high-throughput crystallization experiments are another product of structural genomics making new avenues for research by stimulating fragment-based drug discovery. Finally, a number of ligand-based assessments that rely on the availability of protein-ligand complexes will be highlighted.

Binding Site Prediction and Annotation

Binding site prediction is not only critical in docking to limit the search space, but also plays a critical role for the annotation of protein function. The structural genomics consortia (Chapter 40) aims to solve crystal structures of novel folds and identifying active sites can play a critical role in understanding protein function. Binding site annotation can be used to investigate differences and similarities within a protein family, to either identify potential off-targets or guide optimization of leads. Drug toxicity is usually a result of a drug binding to other protein targets (off-targets) than the intended target the compound was designed for. Being able to identify potential off-targets early on in the development of a drug can be critical in the development of the drug.

While functional assignment is relatively straightforward for proteins with sequence or structural homology to proteins of known function, this is not the case for proteins without a close homologue. Binding sites can be experimentally identified through systematic alanine scanning (DeLano, 2002). Unfortunately, this is a time-consuming and costly process which is why the development of computational methods that can identify active sites and critical residues for protein function is of interest.

A number of groups have used large-scale structural analyses of known protein-ligand complexes to distinguish feature properties of binding sites from the rest of the protein surface. Herzberg and Moult discovered that functional sites often contain residues that are constrained in uncommon conformations. The restricted conformation imposed on the residue is a constraint demanded by the function, whether for catalytic or structural purposes within the binding site (Herzberg and Moult, 1991). Similarly, Zhu and Karlin found that functionally important sites often contain clusters of charged residues. Again, these charged residues could either be required functionally or structurally (Karlin and Zhu, 1996). As such, charged residue such as these can be identified using continuum electrostatics methods based on the assumption that charged residues of functional importance are destabilizing to the protein as shown experimentally through site-directed mutagenesis (Elcock, 2001).

Other distinguishing features include amino acid composition and size of surface cavities. Amino acid composition in binding sites is another feature that can also be used to distinguish the true binding site with a-spheres. Analysis of 15,232 binding sites shows that binding sites are enriched in aromatic residues and methionine. In 611 of 756 proteins the true binding site had the highest protein-ligand binding (PLB) index, a success rate of 79% (Soga et al., 2007). Probes for protein surface cavities have been developed by Nayal and Honig using two molecular surfaces created by different probe sizes. Drug binding cavities are detected based on a random forest classifier trained on 408 properties of cavities. They also performed a large-scale analysis of the properties of cavities (Nayal and Honig, 2006).

Finally, the CPASS database was developed to store the active site residues of ~42,000 known protein-ligand complexes which can subsequently be used to identify similar binding sites in proteins of unknown function when the structure becomes available (Powers et al., 2006). This compilation can also serve to further identify other structural features and properties of binding sites that can be leveraged to improve current binding site prediction methods.

Rather than rely on the availability of structural information to identify binding sites, sequence information can provide additional insight. Amino acid patterns have been developed for different types of functional sites using known structures, and these patterns can subsequently be used to identify similar binding sites in other proteins (Atwood, 2000). However, due to sequence variation, these methods are not that reliable. Lichtarge developed the evolutionary trace (ET) method, which defines conserved residues within clusters of proteins within protein families. The conserved clusters are related to function and generally occur in active sites. When mutations are observed, this often concur with novel functionality (Lichtarge, Bourne, and Cohen, 1996). The ET method was extended to improve the identification of binding sites in proteins and eliminate the requirement of a manually curated sequence alignment. The method strictly relies on sequence information, derived from multiple sequence alignments of protein families. Residues are identified through multiple sequence alignments to be highly correlated with functional divergences when mutated. With the addition of the Rank Information measure, functional sites can be identified in a fully automated fashion, making it available for large-scale identification of binding sites (Yao, Mihalek, and Lichtarge, 2006).

The annotation of binding sites is also an active area of research, because it allows for the identification of similar binding sites and distinguishes differences between related targets that are important for lead optimization. The GRID program, developed by Goodford (Goodford, 1985), identifies favorable interaction points for different types of small probes. The low-energy positions of these probes can be used to optimize small-molecule ligands. The molecular interaction fields (MIF) generated by GRID have been used to distinguish different kinase families using PCA analysis (Naumann and Matter, 2002). The differences between related binding sites identified using MIF and PCA analysis has been used to design selective ligands (Vulpetti et al., 2005). GRID is also used by Mason and Cheney to generate site points for a number of receptors and generated all four-point pharmacophores for the binding sites. By calculating the overlap between all four-point pharmacophores of a ligand to all four-point pharmacophores of an active site, specificity of a ligand to its target versus off-targets could be ascertained (Mason and Cheney, 1999).

Cavbase derives pseudo-centers based on the underlying amino acid properties for binding sites directly to annotate binding sites. The pseudo-centers represent potential hydrogen bonding and aromatic interaction points in the binding site. The pseudo-centers are mapped onto the cavity surface and a clique-detection algorithm is applied to compare different binding sites. Using Cavbase binding sites with similar function, but stemming from proteins with different folds can be retrieved. Different protein families and subfamilies within a protein family can be clustered using the Cavbase description also (Kuhn et al., 2006).

Singh and coworkers developed the structural interaction fingerprint (SIFt) methodology (Deng, Chuaqui, and Singh, 2004). SIFt is simply a one-dimensional binary string derived from protein-ligand crystal structures and represents how the ligand interacts with the protein. An extension, profile-SIFt (p-SIFT), can be used to highlight differences in the active site within a protein family based on protein-ligand interactions observed complex structures (Chuaqui et al., 2005).

Earlier we mentioned the term ’’drugability’’ of protein binding sites. Drugability is defined as the potential of the target to respond to a small molecule designed to elicit a biological response. A critical parameter for a potential drug is the affinity, which can be measured by the Kd or IC50 for example, for the target. The size and depth of the binding site play a critical role in determining whether a high-affinity molecule can be developed, but other factors play a role also. Cheng et al. (2007) developed a method to calculate the maximal achievable binding energy for a binding site. The method relies on estimating the desolvation of the binding site, which is related to the size of the binding site and the curvature of the surface. This simple model was able to distinguish known drugable targets from known undrugable targets.

The predetermination of whether a target is drugable or not is becoming more important in this genomic and proteomic era where novel potential targets are identified on a large scale. This is underscored by the fact that most drugs currently on the market only target a limited number of receptors. It is estimated that ~1200 small molecule drugs only target 324 molecular targets for both human targets and pathogenic organisms (Overington, Al-Lazikani, and Hopkins, 2006).

Structure Selection for Virtual Screening

Many targets have several crystal structures that can be used as a template for drug screening. Some structures might be holo (ligand bound), others might be apo (no ligand bound) structures. Choosing the structure that is most appropriate for virtual screening might not be straightforward. Shoichet showed for 10 systems that the holo form of the protein is generally superior to the apo-form in virtual screening enrichments. In addition, usually both the holo-and the apo-form of the protein have higher enrichments than homology models built for the same receptors. Encouragingly, homology models do show enrichments better than random in most cases (McGovern and Shoichet, 2003). A kinase-specific study of the use of homology models in virtual screening showed good enrichment for five models as well, but one model gave negative enrichment (Diller and Li, 2003).

There appears to be a relationship between the success of virtual screening with the sequence identity or homology of the target sequence with the template used to build the homology model. A retrospective study showed that similar enrichment factors can be achieved for homology models versus crystal structures as long as similarity is greater than 60% (Oshiro et al., 2004). In contrast, Gilson’s laboratory showed by docking against multiple homology models built for the same target, enrichment correlated poorly with sequence identity between the target and the template (Fernandes, Kairys, and Gilson, 2004). The shape of the binding site in the template possibly plays a more important role for a more accurate screen.

Rockey and Elcock assessed whether the cocrystallized ligand plays in role in predicting the correct binding modes against the homology model. A number of homology models were built using kinase structures bound to staurosporine. The results of re-docking staurosporine (a pan-kinase inhibitor) into homology models built from a staurosporine-bound template structure was compared to docking results in models built from templates without a cocrystallized ligand or bound to a different ligand. The authors demonstrated that the binding mode prediction using models generated from templates bound to the same ligand is often better than docking the apo structures or templates bound to a chemically different ligand. Virtual screening experiments have not been performed to assess the potential improvements based on these findings, but the observations are in line with studies highlighted above that showed ligand-bound structures are better for virtual screening than the apo structures (Rockey and Elcock, 2006).

While these retrospective studies show the potential utility of virtual screening, a number of prospective, or truly predictive, studies have also appeared. Again, the use of virtual screening to identify leads is highlighted by these studies (Alvarez, 2004).

Receptor-Based Ligand Specificity Predictions

Binding site annotation can be used to identify similar binding sites, and thus off-targets. More recently, a number of methods have been developed to identify additional targets for ligands by interaction energy calculations. Elcock’s laboratory developed the SCR scoring function to identify off-targets of kinase ligands. Models for potential off-target kinases were built using the backbone coordinates of the target structure. Amino acid side chains in the binding site for the off-targets are optimized around the ligand and the interaction energy for each protein-ligand complex is calculated using a simple empirical scoring function. High-affinity targets for a number of kinase ligands were successfully identified, although the calculations were not successful for each ligand (Rockey and Elcock, 2005).

Page and Bates applied the MM-PBSA method (Kollman et al., 2000) to the identification of off-targets of kinase inhibitors. The MM-PBSA method involves the generation of molecular dynamics trajectories of the complexes and calculates average free energies over the trajectory. The aim of this strategy is to account for conformational changes that may occur in a protein structure leading to the formation of an appropriate binding pocket creating the potential for ligand interaction. Unfortunately, the results were not very encouraging, possibly due to the inherent approximations made by the MM-PBSA method (Page and Bates, 2006).

INVDOCK was designed to screen ligands against multiple protein cavities and limited receptor flexibility is allowed. Upon flexible ligand docking against a rigid receptor, both the ligand and the receptor are allowed to move during the subsequent energy minimization. To identify potential off-targets, the score of a ligand against other receptors is compared to the score of the ligand against its known target. Initial results are encouraging in that a number of confirmed targets for tamoxifen and vitamin E were identified based on docking scores against these targets, although a number of known targets of these molecules were missed. In addition, a number of unconfirmed targets were identified using the INVDOCK procedure (Chen and Zhi, 2001).

The use of structurally conservative and nonconservative amino acid mutations is also explored to compare binding site similarities between kinases and how these impact the specificity of kinase inhibitors. It was shown that targets of the same inhibitor have similar residues at all positions that are important for binding of the ligand (Sheinerman, Giraud, and Laoui, 2005).

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery

Drug discovery has traditionally focused on identifying molecules that exhibit activity in a biochemical assay for a particular target. The library sizes that are screened in the biochemical assay have increased significantly over the years with the development of high-throughput screening and combinatorial chemistry. However, these techniques have not led to a significant change in the productivity of drug discovery (Hird, 2000). Compound libraries of pharmaceutical companies generally consist of historical compounds synthesized for previous projects attenuated by compounds synthesized and purchased to enhance the diversity of the collection. While the number of compounds in these collections has increased significantly (up to 2 million compounds) this still covers only a small fraction of accessible chemical space.

Lipinski assessed the physical-chemical properties of clinically tested drug molecules and was able to define the rule-of-five, which consists of physical-chemical properties shared by these molecules (see Chapter 34). After elimination of potential candidates based on these rules, the size of the chemical drug-like space consists of ~1060molecules (Bohacek, McMartin, and Guida, 1996) and screening ~1 million compounds leaves 1055 drug-like compounds unscreened. In addition, HTS is used to identify starting points for further optimization, not for the identification of the final drugs. Based on retrospective analyses, it has been shown that ligand properties such as molecular weight, log P, and the number of hydrogen-bond donating and accepting groups increases as the leads are optimized for potency against their target (Teague et al., 1999; Hann, Leach, and Harper, 2001). Log P is a measure of the hydrophobicity of a molecule and is determined by measuring the concentration of the compound in octanol and water. The increase in these different properties during lead optimization led to a modified definition of lead-like properties that are often used in the analysis of HTS data, to design virtual screening libraries and in the design of libraries for synthesis in library enhancement efforts.

While chemical space for lead-like compounds (molecular weight ~350 Da) is significantly smaller than the drug-like space, it still consists of ~1025 compounds. Fragment-space however, becomes significantly more accessible, as there are only ~14 million compounds at <160Da (Fink, Bruggesser, and Reymond, 2005). However, the affinity of these fragments for the target is generally between 100 LiM and 100 mM and identifying these fragments in biochemical assays is not straightforward. The limitations in designing a suitable biochemical assay are partially effected by detection limits, but also because the screening concentration has to be very high to detect inhibition. Most compounds are not soluble enough to be screened at such high concentrations. A number of non-biochemical approaches have been used to pursue fragment-based drug discovery in recent years, among these are NMR, X-ray crystallography, and the tethering approach, to be further discussed later.

Fragment-based design can be traced back to the SAR-by-NMR technique developed by Abbott (Shuker et al., 1996). It was shown that binding of low-affinity compounds (mM range) could be detected by identifying chemical shifts in the target NMR spectrum. By either observing different chemical shifts induced by different fragments, or by screening fragments in the presence of an excess amount of a previously identified fragment, compounds that bind in different binding pockets can be identified. Fragments interacting with different parts of the protein can be subsequently linked. Proper linking of the weak fragments can result in non-additive enhancements in potency, leading to sub-micromolar compounds (Shuker et al., 1996).

In the SAR-by-NMR technique the binding modes of the active fragments are generally not identified. A number of groups have instead adopted high-throughput crystallography to identify fragments that bind to the target of interest. Generally mixtures of fragments are soaked into existing crystals of the target of interest. Both hardware and software developments have improved the practicality of using X-ray crystallography to identify fragments for further optimization (Hartshorn et al., 2005; Blaney, Nienaber, Burley, 2006). Upon identification of the exact binding mode of the fragment(s), structure-based lead optimization approaches can be used to increase the potency of the fragment for the target of interest and to develop a drug-like molecule.

The tethering strategy to identify binding partners developed by Sunesis involves identifying fragments that have formed a covalent bond to a cysteine in the protein. The formation of the covalent bond enhances the affinity of the fragment for the protein surface, enabling detection. Detection is done using mass spectrometry (MS). If a cysteine is not present near the area of interest, mutagenesis can be used to produce protein with a cysteine in the right position (Erlanson, Wells, and Braisted, 2004).

Computationally, most de novo design tools use fragments to design ligands from scratch that are complementary to the site of interest. A number of tools have been developed that explore protein surfaces with small probes (Goodford, 1985; Miranker and Kar-plus, 1991) which can also be used as starting points for drug discovery. Docking can of course also be used to screen libraries that contain only fragments. However, most fragment-based drug discovery programs use a tiered approach, starting with initial identification of active fragments through experimental techniques and subsequently optimizing fragments using input from structure-based design.

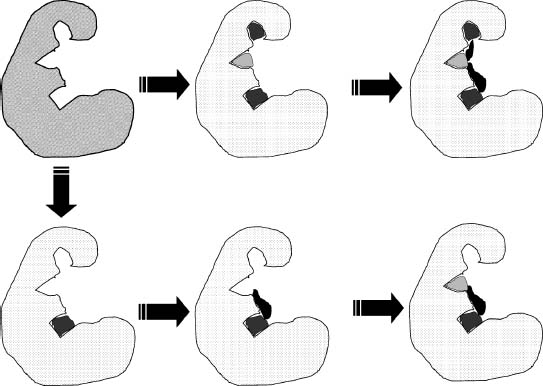

A number of different approaches can be used to find leads from fragments. The first approach, fragment evolution, uses the identified fragment as a platform to add interactions with nearby pockets on the protein surface (Figure 27.4). The second approach, fragment linking, uses two or more fragments that are known to bind to different pockets on the protein surface and construct linkers that can optimally connect the fragments (Figure 27.4). At a later stage, it might be necessary to replace the originally found fragment with some other fragment to optimize other properties than affinity, for example specificity or solubility. This is called fragment-based optimization.

Figure 27.4. Fragment-based drug discovery. Illustrated are the two main approaches to fragment-based drug discovery. The top path shows how different fragments are identified that form interactions with different pockets in the binding site. In the next step, linkers are designed that can link the fragments together without disturbing the interactions made by the fragments. The bottom path illustrates the growth approach to fragment-based discovery in which one starts from a single fragment and grows the fragment to form interactions with nearby pockets in the binding site.

Ligand-Based Perspectives

In this section, a number of different studies are highlighted that have used large-scale ligand-based analyses that can aid in the further optimization of new leads. Just as similar proteins, either based on structure or sequence, often exhibit similar biological functions, one can investigate this for ligands as well. Usually, similar ligands are assumed to bind to similar proteins and thus to have similar biological activities. This is the driving force behind the use of ligand-based similarity measures to identify additional ligands for a particular target. Shoichet’s group developed the similarity ensemble approach (SEA), which relates receptors to each other based on the similarity of their ligands. Sixty-five thousand annotated ligands were used and 246 receptors. Using this method, a network of pharmacological space could be constructed and showed clustering of for example the nuclear hormone receptors and the distinct pharmacology of otherwise related proteins. This method can be used to form hypotheses of potential off-targets of ligands, which can then be confirmed experimentally by measuring the affinity of that ligand for the identified potential target (Keiser et al., 2007).

Jain and coworkers also used ligand-based methods to show that they can be used to identify ligands that have the same biological target. Similarity between ligands targeting different receptors can potentially highlight off-target effects, and could thus possibly be used to predict side effects before entering the clinic (Cleves and Jain, 2006).

Three molecules that are found in a large number of cocrystal structures, namely ATP, NAD, and FAD, were investigate to assess the conformational diversity of ligands bounds to proteins. These ligands bind to evolutionarily unrelated proteins, which allows an assessment of conservation of the binding mode of these ligands. The authors observed large conformational variations in the ligands bound to different proteins, and even within homologous superfamilies, each of the studied molecules can adopt a wide range of conformations (Stockwell and Thornton, 2006).

Although a number of studies have shown that chemically similar ligands can occasionally adopt different binding modes depending on either the experimental conditions (Davis, Teague, Kleywegt, 2003) or changes to the ligand, no systematic study had been done to solidify this generalization until recently. To address this issue, Bostoni and coworkers conducted a systematic study that exhaustively searched all available protein-ligand structures in the PDB. The search retrieved 1484 binding sites of interest with 206 binding site pairs that bind similar ligands. A comparison was made between the binding sites, to analyze changes in ligand conformation based on conserved water molecules, side chain positions, and other potential factors. Water molecules can have a profound influence of ligand binding since they may mediate hydrogen bonds between the ligand and the protein. In ~70% of the cases, the positioning of waters molecules in the binding site pairs differs. Amino acid side chains play an important role in forming interactions with the ligand and in determining the shape of the binding site. In ~50% of the binding site pairs, different rotamers for amino acid side chains were observed, but backbone movements were rare (Bostroem, Hogner, and Schmitt, 2006). Both these observations underscore the necessity of developing methods for docking that take into account the role of explicit water molecules and binding site flexibility. Although structural changes in the binding site are observed for similar ligand pairs, it is important to note from this study that the orientation of the ligands in the binding site was conserved (Bostroem, Hogner, and Schmitt, 2006).

Rather than select for leads based on initial potency, other parameters such as molecular weight of the compound and ligand efficiency are being considered during the selection process. High-molecular-weight compounds often have poor solubility and permeability, which can lead to poor in vivo activity. During lead optimization, the molecular weight of the compounds generally increases therefore it is important to start with leads of smaller, reasonable molecular weight. Ligand efficiency has also become a parameter for lead consideration defined as the binding free energy per non-hydrogen atom ΔGefficiency (Hopkins, Groom, and Alex, 2004; Abad-Zapatero and Metz, 2005):

(27.6)

In essence this metric normalizes the potency by the size of the ligand, and can be substituted with other metrics of size, such as molecular weight or the polar surface area (PSA; Abad-Zapatero and Metz, 2005). The use of this metric results in highlighting low molecular weight compounds that are less potent than larger molecules, but have a larger contribution of each atom to the overall potency.

Ligand-based analyses have also critically contributed to improving the design and augmentation of chemical libraries when purchasing commercial compounds to expand the corporate collection. On the one hand compounds should be purchased that are not represented in the current collection in order to increase the amount of chemical space that is being sampled by the general purpose HTS collection. Diversity calculations can be used for this. On the contrary, each chemical series needs to be represented by more than a single molecule in the collection to improve the likelihood of identifying that series in a biological screen against the relevant target. Using a retrospective analysis of HTS data based on a number of assumptions, it was estimated that between 50 and 100 analogues are needed for each chemical series to identify each active series (Nilakantan, Immermann, and Haraki, 2002).

SUMMARY

To conclude, while docking is important for many other facets of research, the importance of docking is placed in the context of drug screening and development. Mainly because the advantages of coupling computational screens and modeling of biologically active compounds help facilitate an otherwise time consuming and expensive process. The hope is that these in silico approach will help reduce and better manage resources. The need for such virtual screening also drives improved technology to identify suitable matches between the compounds and targets that collectively have pharmacological impact. As demonstrated in this chapter, there are strengths and limitations associated with both physics or heuristic based algorithms. However, with improvements in computational resources and our growing knowledge of the binding process and drug efficacy, docking and virtual screening will play an increasingly important role in expediting drug discovery.