3

FUNDAMENTALS OF DNA AND RNA STRUCTURE

INTRODUCTION

In 1946, Avery provided concrete experimental evidence that DNA was the main constituent of genes (Avery et al., 1944); universal acceptance of this idea came with the publication of the Hershey-Chase experiments (Hershey and Chase, 1951). After the seminal discovery of the double helical nature of DNA in 1953 (Watson and Crick, 1953), the focus of nucleic acid structural research turned to fiber diffraction of natural and defined sequences (Arnott 1970; Arnott, Campbell Smith, and Chandrasekaran, 1976a). Through these studies, we gained many insights into nucleic acid structure. We learned that hydration, ionic strength, and sequence affect conformation type and that nucleic acids can adopt a wide variety of structures including single-stranded helices (Arnott, Chandrasekaran, and Leslie, 1976b) and parallel helices (Rich et al., 1961), as well as triple and quadruple helices (Arnott, Chandrasekharan, and Marttila, 1974).

Once it was possible to synthesize and purify oligonucleotides (Khorana et al., 1956), crystallography and later NMR could be used to determine nucleic acid structures. The first crystal structure that was identified as containing all the components that could have allowed us to see a double helix was a very small piece of RNA—the dinucleoside monophosphate Up Å (Seeman et al., 1971). But rather than forming a double helix, it displayed unusual conformations, anticipating some of the many conformations that we now know exist in nucleic acids. In 1973, the double helix was visualized at atomic resolution with the determination of the crystal structures of two self-complementary RNA fragments, ApU and GpC (Rosenberg et al., 1973). The determination of the structures of dinucleoside phosphates complexed with drugs followed and laid the foundation for nucleic acid recognition (Tsai et al., 1975).

The publication in 1980 of a structure of more than a full turn of B-DNA (Wing et al., 1980) laid aside the doubts of even the most skeptical researchers (Rodley et al., 1976) that DNA was a right-handed double helix. The structure was also a milestone in our understanding of the fine structure of DNA, whereby it was possible to determine the effects of sequence on structure. Interestingly, it was at the same time that the structure of an unusual left-handed form of DNA—Z-DNA—was solved (Wang et al., 1979).

In parallel with the studies of these synthetic oligonucleotides, researchers were successful in purifying transfer RNA. The publication of the structure of yeast Phe tRNA in 1974 (Kim et al., 1974; Robertus et al., 1974) represented the first and until relatively recently, the only example of a natural intact nucleic acid structure. Now we are seeing an ever-increasing number of structures of RNA that are giving us insights into the RNA world.

In this chapter, we present the principles of nucleic acid structure. We then present a brief overview of the current state of our knowledge of nucleic acid structure determined using X-ray crystallographic methods. Further details on individual nucleic acid structures are provided in the recent book by one of us (Neidle, 2007). Discussion of nucleic acids in complex with proteins is dealt in Chapter 25.

CHEMICAL STRUCTURE OF NUCLEIC ACIDS

In the early years of the twentieth century, chemical degradation studies on material extracted from cell nuclei established that the high molecular weight “nucleic acid” was actually composed of individual acid units termed nucleotides. Four distinct types were isolated—guanylic, adenylic, cytidylic, and thymidylic acids. These could be further cleaved to phosphate groups and four distinct nucleosides. The latter were subsequently identified as consisting of a deoxypentose sugar and one of the four nitrogen-containing heterocyclic bases. Thus, each repeating unit in a nucleic acid polymer constitutes these three units linked together—a phosphate group, a sugar, and one of the four bases.

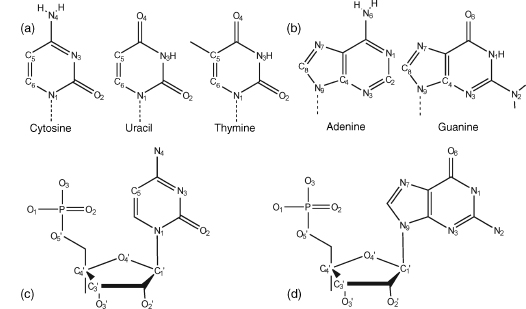

The bases are planar aromatic heterocyclic molecules and are divided into two groups—the pyrimidine bases thymine and cytosine, and the purine bases adenine and guanine. Their major tautomeric forms are shown in Figure 3.1. Thymine is replaced by uracil in ribonucleic acids. RNA also has an extra hydroxyl group at the 2’ position of its pentose sugar groups. The sugar present in RNA is ribose; in DNA, it is deoxyribose. The standard nomenclature for the atoms in nucleic acids is shown in Figure 3.1. Accurate bond length and angle geometries for all bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides have been well established by X-ray crystallographic analyses. The most recent surveys (Clowney et al., 1996; Gelbin et al., 1996) have calculated mean values for these parameters (at equilibrium) from the most reliable structures in the Cambridge Structural Database (Allen et al., 1979) and the Nucleic Acid Database (Berman et al., 1992). These have been incorporated in several implementations of the AMBER (Weiner and Kollman, 1981; Case et al., 2005) and CHARMM (Brooks et al., 1983) force fields, widely used in molecular mechanics and dynamics modeling and in a number of computer packages for both crystallographic and NMR structural analyses (Parkinson et al., 1996). Accurate crystal-lographic analyses, at very high resolution, can also directly yield quantitative information on the electron density distribution in a molecule, and hence on individual partial atomic charges. These charges for nucleosides have hitherto been obtained by ab initio quantum mechanical calculations, they but are now available experimentally for all four DNA nucleosides (Pearlman and Kim, 1990).

Figure 3.1. Chemical composition and nomenclature of nucleic acid components. (a) Pyrimidines. Uracil occurs in RNA, and DNA base thymine has a methyl group attached to C5. (b) Purines. (c) A pyrimidine nucleotide, shown is cytidine-5’-phosphate. (d) A purine nucleotide, shown is guanosine-5’-phosphate.

Individual nucleoside units are joined together in a nucleic acid in a linear manner through phosphate groups that are attached to the 3’ and 5’ positions of the sugars (Figure 3.1c and d). Hence, the full repeating unit in a nucleic acid is a 3’, 5’-nucleotide.

For nucleic acid and oligonucleotide sequences, single-letter codes for the five unit nucleotides are used—A, T, G, C, and U. The two classes of bases can be abbreviated as Y (pyrimidine) and R (purine). Phosphate groups are usually designated as “p”. A single oligonucleotide chain is conventionally numbered from the 5’-end; for example, ApGpCpTpTpG has the 5’ terminal adenosine nucleoside, with a free hydroxyl at its 5’position, and thus the 3’-end guanosine has a free 3’ terminal hydroxyl group. Intervening phosphate groups are sometimes omitted when a sequence is written down. Chain direction is sometimes emphasized with 5’ and 3’ labels. Thus, an antiparallel double helical sequence can be written as

5’CpGpCpGpApApTpTpCpGpCpG

3’GpCpGpCpTpTpApApGpCpGpC

or simply as (CGCGAATTCGCG)2. In structural publications, the prefix “d” is usually applied to a DNA sequence, as in d(CGAT) to emphasize that the oligonucleotide is a deoxyribose rather than an oligoribonucleotide.

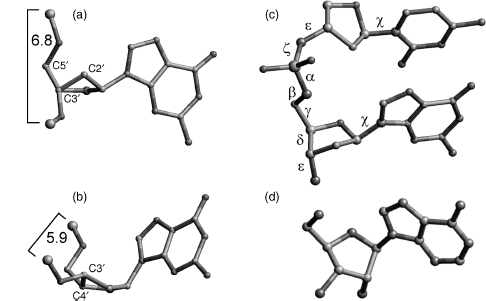

The bond between sugar and base is known as the glycosidic bond. Its stereochemistry is important. In natural nucleic acids, the glycosidic bond is always in the β stereochemistry, which is to say that the base is above the plane of the sugar when viewed onto the plane and therefore on the same face of the plane as the 5’ hydroxyl substituent (Figure 3.2d). The absolute stereochemistry of other substituent groups on the deoxyribose sugar ring of DNA is defined such that when viewed end on with the sugar ring oxygen atom O4’ at the rear, the hydroxyl group at the 3’ position is below the ring and the hydroxymethyl group at the 4’position is above.

Figure 3.2. Structural features and stereochemistry of nucleic acid components. (a) C2’-endo sugar pucker, typical for B-DNA. Atom C3’, labeled, is in front and conceals atom C4’. Atoms C2’ and C5’ point both “up”. Two consecutive P atoms have typical distance about 6.4–6.9Å. (b) C3’-endo sugar pucker, typical for A-form nucleic acids (shown for deoxyribose, as in (a)). In C3’-endo, atom C3’ is “above” the plane of the remaining four sugar ring atoms. P–P distances are shorter than in the case of the C2’-endo pucker, between 5.4 and 6.2Å .(c) Definition of the backbone torsion angles: α=O3’–P–O5’–C5, β=P–O5’–C5’–C4’, γ =O5’–C5’–C4’–C3’, δ =C5’–C4’–C3’–O3’, ε=C4’–C3’–O3’–P, and ζ=C3’–O3’–P–O5’. Torsions around the glycosidic bonds are defined as χ=O4’-C1’-N1-C2 for pyrimidines (shown is cytosine) and χ=O4’-C1’-N9-C4 for purines (shown is guanine). (d) Stereochemistry of a natural β-nucleoside.

A unit nucleotide can have its phosphate group attached at the either 3’-or5’-ends and is thus termed either a 3’ or a 5’ nucleotide. It is chemically possible to construct α-nucleosides and from them α-oligonucleosides, which have their bases in the “below” configuration relative to the sugar rings and their other substituents. These are much more resistant to nuclease attack than standard natural β-oligomers and have been used as antisense oligomers to mRNAs because of their superior intracellular stability.

BASE-PAIR GEOMETRY

The realization that the planar bases can associate in particular ways by means of hydrogen bonding was a crucial step in the elucidation of the structure of DNA. The important early experimental data of Chargaff (Zamenhof, Brawermann, and Chargaff, 1952) showed that the molar ratios of both adenine: thymine and cytosine: guanine in DNA were unity. This led to the proposal by Crick and Watson that in each of these pairs, the purine and pyrimidine bases are held together by specific hydrogen bonds to form planar base pairs. In native double helical DNA, the two bases in a base pair necessarily arise from two separate strands of DNA with intermolecular hydrogen bonds that hold the DNA double helix together (Watson and Crick, 1953).

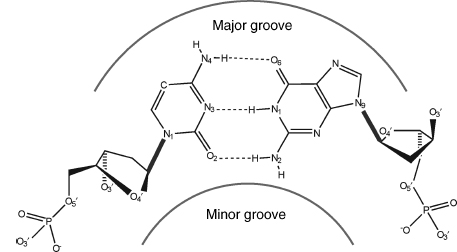

Figure 3.3. The canonical Watson–Crick base pair, shown as the G-C pair. Positions of the minor and major grooves are indicated. The glycosidic sugar–base bond is shown by the bold line; hydrogen bonding between the two bases is shown in dashed lines.

The adenine:thymine (AT) base pair has two hydrogen bonds compared to the three in a guanine: cytosine (GC) one (Figure 3.3). Fundamental to the Watson-Crick arrangement is that the sugar groups are both attached to the bases asymmetrically on the same side of the base pair. This defines the mutual positions of the two sugar-phosphate strands in DNA itself. Atoms at the surface of the sugar phosphate backbone define two indentations with different dimensions called minor and major grooves. By convention, the major groove is faced by C6/N7/C8 purine atoms and their substituents and by C4/C5/C6 pyrimidine atoms and their substituents, and the minor groove by C2/N3 purine and C2 pyrimidine atoms and their substituents.

The two base pairs are required to be almost identical in dimensions by the Watson-Crick model. High-resolution (0.8-0.9 Å) X-ray crystallographic analyses of the ribodinu-cleoside monophosphate duplexes (GpC)2 and (ApU)2 by A. Rich and colleagues in the early 1970s has established accurate geometries for these AT and GC base pairs (Rosenberg et al., 1976; Seeman et al., 1976). These structure determinations showed that there are only small differences in size between the two types of base pairings, as indicated by the distance between glycosidic carbon atoms in a base pair. The C1’ ...C1’ distance in the GC base-pair structure is 10.7 Å and 10.5 Å in the AU-containing dinucleoside.

The individual bases in a nucleic acid are flat aromatic rings, but base pairs bound together only by nonrigid hydrogen bonds can show considerable flexibility. The vertical arrangement of bases and base pairs is flexible and restrained mainly by stacking interactions of bases. This flexibility to some extent depends on the nature of the bases and base pairs themselves, but is more related to their base-stacking environments. Thus, descriptions of base morphology have become important in describing and understanding many sequence-dependent features and deformations of nucleic acids. The sequence-dependent features are often considered primarily at the dinucleoside local level, whereas longer range effects, such as helix bending, can also be analyzed at a more global level.

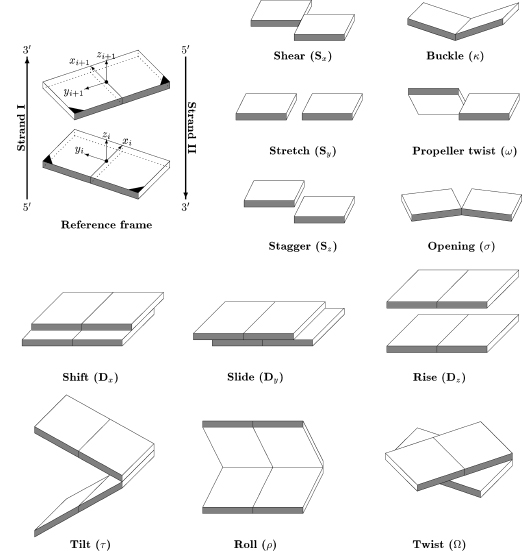

A number of rotational and translational parameters have been devised to describe these geometric relations between bases and base pairs, which were originally defined in the 1989 “Cambridge Accord” (Dickerson et al., 1989). These definitions, together with the Cambridge Accord sign conventions, are given for some key base parameters.

Propeller twist (ω) between bases is the dihedral angle between the normal vectors to the bases, when viewed along the long axis of the base pair. The angle has a negative sign under normal circumstances, with a clockwise rotation of the nearer base when viewed down the long axis. The long axis for a purine-pyrimidine base pair is defined as the vector between the C8 atom of the purine and the C6 of a pyrimidine in a Watson-Crick base pair. Analogous definitions can be applied to other nonstandard base pairings in a duplex including purine-purine and pyrimidine-pyrimidine ones.

Buckle (k) is the dihedral angle between bases, along their short axis, after propeller twist has been set to 0°. The sign of buckle is defined as positive if the distortion is convex in the direction 5’ → 3’ of strand 1. The change in buckle for succeeding steps, termed cup, has been found to be a useful measure of changes along a sequence. Cup is defined as the difference between the buckle at a given step and that of the preceding one.

Inclination (η) is the angle between the long axis of abase pair and aplane perpendicular to the helix axis. This angle is defined as positive for right-handed rotation about a vector from the helix axis toward the major groove.

X and Y displacements define translations of abase pair within its mean plane in terms of the distance of the midpoint of the base pair long axis from the helix axis. X displacement is toward the major groove direction, when it has a positive value. Y displacement is orthogonal to this, and it is positive if toward the first nucleic acid strand of the duplex.

The key parameters for base-pair steps are as follows:

Helical twist (Ω) is the angle between successive base pairs, measured as the change in orientation of the C1’-C1’ vectors on going from one base pair to the next, projected down the helix axis. For an exactly repetitious double helix, helical twist is 360°/n, where n is the unit repeat defined above.

Roll (ρ) is the dihedral angle forrotation of onebasepair with respect its neighbor about the long axis of the basepair. Apositive roll angle opens up abase-pair step toward the minor groove. Tilt (τ) is the corresponding dihedral angle along the short (i.e., x-axis) of the base pair.

Slide is the relative displacement of one base pair compared to another, in the direction of nucleic acid strand 1 (i.e., the Y displacement), measured between the midpoints of each C6-C8 base pair long axis.

Unfortunately, there is now some confusion in the literature regarding these parameters, in part because the Cambridge Accord did not define a single unambiguous convention for their calculation, and two distinct types of approaches have been developed to calculate them (Lu et al., 1999). In one approach, the parameters are defined with respect to a global helical axis that need not be linear. The other uses a set of local axes, one per dinucleotide step. Another ambiguity is that a variety of definitions of local and global axes have been used. Fortunately, the overall effect for most undistorted structures is that only a minority of parameters appear to have distinctly different values depending on which method of calculation is used by the widely available programs: CEHS/SCHNAaP (El Hassan and Calladine, 1995; Lu, El Hassan, and Hunter, 1997), CompDNA (Gorin, Zhurkin, and Olson, 1995; Kosikov et al., 1999), Curves (Lavery and Sklenar, 1988; Lavery and Sklenar, 1989), FREEHELIX (Dickerson, 1998), NGEOM (Soumpasis and Tung, 1988; Tung et al., 1994), NUPARM (Bhattacharyya and Bansal, 1989; Bansal et al., 1995), and RNA (Babcock et al., 1993; Babcock and Olson, 1994; Babcock et al., 1994).

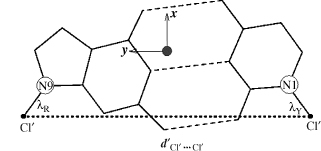

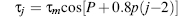

To resolve the ambiguities in description of base morphology parameters (Figure 3.4), a standard coordinate reference frame for the calculation of these parameters has been proposed (Lu and Olson, 1999) and endorsed by the successor to the Cambridge Accord, the 1999 Tsukuba Accord (Olson etal., 2001). The right-handed reference frame is shown in Figure 3.5. It has the x-axis directed toward the major groove along the pseudo-twofold axis (shown as •) of an idealized Watson-Crick base pair. The y-axis is along the long axis of the base pair, parallel to the C1’…C1’ vector. The position of the origin clearly depends on the geometry of the bases and the base pair. These have been taken from the published compilations (Clowney et al., 1996; Gelbin et al., 1996). The Tsukuba reference frame is unambiguous and has the advantage of being able to produce values for the majority of local base-pair and base-step parameters that are independent of the algorithm used.

Figure 3.4. Pictorial definitions of some parameters that relate complementary base pairs and sequential base-pair steps. The base-pair reference frame is constructed such that the x-axis points away from the (shaded) minor groove edge. Images illustrate positive values of the designated parameters. Reprinted with permission from Adenine Press from Lu, Babcock, and Olson (1999).

Figure 3.5. Illustration of idealized base-pair parameters, dC1’…C1’ and λ, used respectively, to displace and pivot complementary bases in the optimization of the standard reference frame for right-handed A- and B-DNA, with the origin at • and the x- and y-axes pointing in the designated directions. Reprinted with permission from Olson et al. (2001).

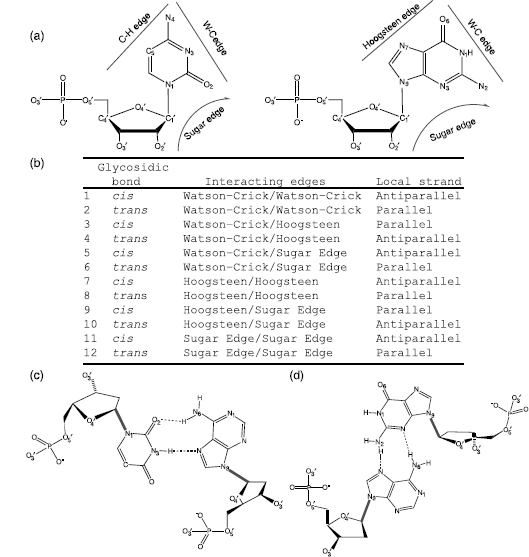

Although Watson-Crick base pairs are the most prevalent type of pairs in nucleic acids, in single-stranded RNA, 40% of the base pairs form other types. A systematic classification has been adopted (Figure 3.6) (Leontis and Westhof, 2001). In this system, base pairing is defined as hydrogen bonding between edges of the interacting bases. Each base has three edges: Watson-Crick, sugar, and Hoogsteen (in purines) or C—H (in pyrimidines) as shown n Figure 3.6a; the classes are defined in Figure 3.6b. The canonical Watson-Crick pair is a CG or AT pair interacting through the Watson-Crick edges with cis mutual orientation of the glycosidic bonds (Figure 3.3) and antiparallel local orientation of the opposing nucleotide strands. Two examples of non-Watson-Crick bonding are shown in Figures Figure 3.6c and d.

Figure 3.6. Base-pairing patterns described by Leontis–Westhof (L-W) nomenclature (Leontis and Westhof, 2001). (a) Definition of the “edges” that can form base pairs with the other base. (b) The 12 base-pair classes in the L-W schema. (c) Noncanonical base pair interacting by Watson–Crick and Hoogsteen edges with trans orientation of glycosidic bonds. This L-W class 4 is important in RNA architecture. (d) L-W class 10 base pair formed by the Hoogsteen and Sugar edges with transorientation of the glycosidic bonds.

CONFORMATION OF THE SUGAR PHOSPHATE BACKBONE

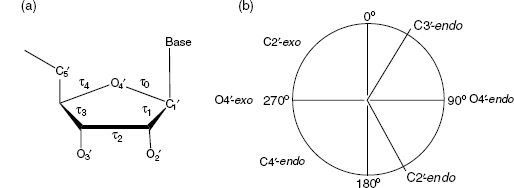

The five-member deoxyribose sugar ring in nucleic acids is inherently nonplanar. This nonplanarity is termed puckering. The precise conformation of a deoxyribose ring can be completely specified by the five endocyclic torsion angles within it (Figure 3.7). The ring puckering arises from the effect of nonbonded interactions between substituents at the four-ring carbon atoms; energetically, the most stable conformation for the ring is that in which all substituents are as far apart as possible. Thus, different substituent atoms would be expected to produce differing types of puckering. The puckering can be described by either a simple qualitative description of the conformation in terms of atoms deviating from ring coplanarity, or precise descriptions in terms of the ring internal torsion angles.

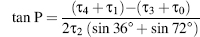

In principle, there is a continuum of interconvertible puckers, separated by energy barriers. These various puckers are produced by systematic changes in the ring torsion angles. The puckers can be succinctly defined by the parameters P and τm (Altona and Sundaralingam, 1972). The value of P, the phase angle of pseudorotation, indicates the type of pucker since P is defined in terms of the five torsion angles τ0-τ4: tanP

and the maximum degree of pucker, τm,by τm = τ2/(cos P).

The pseudorotation phase angle can take any value between 0° and 360°.If τ2 has a negative value, then 180° is added to the value of P. The pseudorotation phase angle is commonly represented by the pseudorotation wheel, which indicates the continuum ofring puckers (Figure 3.7b). Values of τm indicate the degree of puckering of the ring; typical experimental values from crystallographic studies on mononucleosides are in the range of 25-45°. The five internal torsion angles are not independent of each other, and so to a good approximation, any one angle τj can be represented in terms of just two variables:

Figure 3.7. (a) The five internal torsion angles in a ribose ring. (b) The pseudorotation wheel for a deoxyribose sugar with indication of the most important ribose conformers.

Pseudorotation parameters can be calculated interactively using the PROSIT facility (Sun et al., 2004) at http://cactus.nci.nih.gov/prosit/. Phase angle P correlates quite tightly with the backbone torsion δ,C5’-C4’-C3’-O3’, so that the sugar pucker is effectively connected to the backbone conformation; the δ ~ P relation can be described by equation δ = 40° cos(P° + 144°) + 120° (Privé, Yanagi, and Dickerson, 1991).

A large number of distinct deoxyribose ring pucker geometries have been observed experimentally by X-ray crystallography and NMR techniques. When one ring atom is out of the plane of the other four, the pucker type is an envelope one. More commonly, two atoms deviate from the plane of the other three, with these two on either side of the plane. It is usual for one of the two atoms to have a larger deviation from the plane than the other, in which case the result is a twist conformation. The direction of atomic displacement from the plane is important. If the major deviation is on the same side as the base and C4’-C5’ bond, then the atom involved is termed endo. If it is on the opposite side, it is called exo. The most commonly observed puckers in crystal structures of isolated nucleosides and nucleotides are either close to C2’-endo or C3’-endo types (Figure 3.2a and b). The C2’-endo family of puckers has P values in the range 140-185°; in view of their position on the pseudorotation wheel, they are sometimes termed S (south) conformations. The C3 -endo domain has P values in the range — 10 to + 40° , and its conformation is termed N (north). In practice, these pure envelope forms are rarely observed, largely because of the differing substituents on the ring. Consequently, the puckers are then best described in terms of twist conformations. When the major out-of-plane deviation is on the endo side, there is a minor deviation on the opposite, exo side. The convention used for describing a twist deoxyribose conformation is that the major out-of-plane deviation is followed by the minor one, for example, C2’-endo, C3 -exo.

The pseudorotation wheel implies that deoxyribose puckers are free to interconvert. In practice, there are energy barriers between major forms. The exact size of these barriers has been the subject of considerable study (Olson, 1982; Olson and Sussman, 1982). The consensus is that the barrier height depends on the route around the pseudorotation wheel. For interconversion of C2’-endo to C3’-endo, the preferred pathway is via the O4’-endo state, with a barrier of 2-5 kcal/mol found from an analysis of a large body of experimental data (Olson and Sussman, 1982) and a somewhat smaller (potential energy) value of 1.5 kcal/mol from a molecular dynamics study (Harvey and Prabhakarn, 1986). The former value, being an experimental one, represents the total free energy available for interconversion.

Relative populations of puckers can be monitored directly by NMR measurements of the ratio of coupling constants between H1’—H2’ and H3’—H4’ protons. These show that in contrast to the “frozen-out” puckers found in the solid-state structures of nucleosides and nucleotides, there is rapid interconversion in solution. Nonetheless, the relative populations of the major puckers depend on the type of base attached. Purines show a preference for the C2’ -endo pucker conformational type, whereas pyrimidines favor C3 -endo. Deoxyribose nucleosides are primarily at greater than 60% in the C2’-endo form, and ribonucleos-ides favor C3’ -endo. Sugar pucker preferences have their origin in the nonbonded interactions between substituents on the sugar ring and to some extent on their electronic characteristics. The C3’-endo pucker of ribose would have hydroxyl substituents at the 2’ and 3 positions further apart than with the C2’ -endo pucker. Ribonucleosides are therefore significantly more restricted in their mobility than deoxyribonucleotides; this has significance for the structures of oligoribonucleotides. These differences in puckering equilibrium, and hence in their relative populations in solution and in molecular dynamics simulations, are reflected in the patterns of puckers found in surveys of crystal structures (Murray-Rust and Motherwell, 1978).

Correlations have been found from numerous crystallographic and NMR studies, between sugar pucker and several backbone conformational variables, both in isolated nucleosides/nucleotides and in oligonucleotide structures. These are discussed later in this chapter. Sugar pucker is thus an important determinant of oligo- and polynucleotide conformation because it can alter the orientation of C1’,C3’,andC4’ substituents, resulting in major changes in backbone conformation and overall structure, as indeed is found.

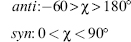

The glycosidic bond links a deoxyribose sugar and a base, being the C1’—N9 bond for purines and the C1’—N1 bond for pyrimidines. The torsion angle % around this single bond can, in principle, adopt a wide range of values, although as will be seen, structural constraints result in marked preferences being observed. Glycosidic torsion angles are defined in terms of the four atoms: O4’—C1’—N9—C4 for purines and O4’—C1’—N1—C2 for pyrimidines.

Theory has predicted two principal low-energy domains for the glycosidic angle, in accord with experimental findings for a large number of nucleosides and nucleotides. The anti conformation has the N1, C2 face of purines and the C2, N3 face of pyrimidines directed away from the sugar ring (Figure 3.8a), so that the hydrogen atoms attached to C8 of purines and C6 of pyrimidines lie over the sugar ring. Thus, the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding groups of the bases are directed away from the sugar ring. These orientations are reversed for the syn conformation, with these hydrogen bonding groups now oriented toward the sugar and especially its O5’ atom (Figure 3.8b). A number of crystal structures of syn purine nucleosides have shown hydrogen bonding between the O5’ atom and the N3 base atom, which would stabilize this conformation. Otherwise, the syn conformation is slightly less preferred than the anti for purines, because of fewer nonbonded steric clashes in the latter case. The principal exceptions to this rule are guanosine-containing nucleotides, which have a slight preference for the syn form because of favorable electrostatic interactions between the exocyclic N2 amino group of guanine and the 5’-phosphate group. For pyrimidine nucleotides, the anti conformation is preferred over the syn because of unfavorable contacts between the O2 oxygen atom of the base and the 5’-phosphate group. The calculated results of molecular mechanics energy minimizations on all four DNA nucleotides in both syn and anti forms, using the AMBER all-atom force field, are fully in accord with these observations.

The sterically preferred ranges for the two domains of glycosidic angles are

Figure 3.8. (a) A guanosine nucleoside with the glycosidic angle χ set in an anti conformation. (b) Guanosine now in the syn conformation.

Values of χ in the region of about —90° are often described as “high anti.” There are pronounced correlations between sugar pucker and glycosidic angle, which reflect the changes in nonbonded clashes produced by C2’ -endo versus C3’ -endo puckers. Thus, syn glycosidic angles are not found with C3’ -endo puckers due to steric clashes between the base and the H3 atom, which points toward the base in this pucker mode.

The phosphodiester backbone of an oligonucleotide has six variable torsion angles (Figure 3.2c), designated as α, β, γ, δ, ε, and ζ, in addition to the five internal sugar torsions τ0…τ4 and the glycosidic angle %. As will be seen, a number of these have highly correlated values and therefore correlated motions in a solution environment. Steric considerations alone dictate that the backbone angles are restricted to discrete ranges (Sundaralingam, 1969; Olson, 1982) and are accordingly not free to adopt any value between 0° and 360°. The fact that angles α, γ, and ζ each have three populated ranges, together with the broad range for angles ε and β that includes two staggered regions, leads to a large number of possible low-energy conformations for the unit nucleotide, especially when glycosidic angle and sugar pucker flexibility are taken into account. In reality, only a small number of DNA oligonu-cleotide and polynucleotide structural classes have actually been observed out of this large range of possibilities; this is doubtless in large part due to the restraints imposed by Watson-Crick base pairing on the backbone conformations when two DNA strands are intertwined together. In contrast, crystallographic and NMR studies on a large number of standard and modified mononucleosides and nucleotides have shown considerably greater conformational diversity. For these, backbone conformations in the solid state and in solution are not always in agreement; the requirements for efficient packing in the crystal can often overcome the modest energy barriers between different torsion angle values. A large range of base-base interactions characterizes many larger RNA molecules, which can therefore adopt a variety of backbone conformations.

A common convention for describing these backbone angles is to term values of -60° as gauche + (g+), —60° as gauche-(g—), and ~180° as trans (t). Thus, for example, angles a (about the P-O5’ bond) and g (the exocyclic angle about the C4’—C5’ bond) can be in the g+, g—, or t conformations. The two torsion angles around the phosphate group itself, Z and a, have been found to show a high degree of flexibility in various dinucleoside crystal structures, with the tg—, g— g—, and g+ g+ conformations all having been observed (Kim et al., 1973). A- and B-DNA adopt to g— g— and tg— conformations; Z-DNA adopts the g+ g+, g+ t, and g—t conformations. The torsion angle b, about the O5’—C5’ bond, is usually near trans. All three possibilities for the g angle have been observed in nucleoside crystal structures, although the g+ conformation predominates in right-handed oligo- and polynucleotide double helices. The torsion angle δ around the C4’—C3’ bond adopts values that relate to the pucker of the sugar ring, since the internal ring torsion angle τ3 (also around this bond) has a value of about 35° for C2’-endo and about 40° for C3’-endo puckers. d is about 81° for C3’-endo and about 140° for C2’-endo puckers.

There are a number of correlations involving these backbone torsion angles, as well as sugar pucker and glycosidic angle, that have been observed in mononucleosides and nucleotides and, more recently, in oligonucleotides (Schneider et al., 1997; Packer and Hunter, 1998; Murthy et al., 1999; Varnai et al., 2002; Murray et al., 2003; Sims and Kim, 2003; Hershkovitz et al., 2003; Schneider et al., 2004). Nucleotides are inherently more flexible in solution as well as being more subject to packing forces in the crystal. Some of the more significant correlations are as follows:

1. Between ζ and α, there are clear distinctions for the A-, B-, and Z-conformational classes (Figure 3.9a) that can be considered an “imprint” characterizing the most important features of local nucleic acid conformation. The ζ/a scattergram shows significant broadening of the torsion distributions in protein/DNA complexes (yellow) and in RNA (red) structures compared to structures of uncomplexed DNA (blue).

Figure 3.9. Backbone conformations in DNA and RNA. 2D scattergrams show conformations of 1861 nucleotides from 186 structures of uncomplexed DNA (darkblue), 5878 nucleotides from 261 structures of DNA in complexes with proteins ordrugs (yellow), and 3752 nucleotides from 132 structures of RNA (red).A, AII, BI, BII, ZI, and ZII are respective double helical forms, Zr/Zy are purine and pyrimidinesteps, respectively, in the Z-form. (a) Conformations at the phosphodiester linkage O3'-P-O5', ζ versus α; (b) torsions a versus γ; (c) relationship between the sugar pucker and the base orientation, δ versus χ. Torsion angles are defined in Figure 3.2. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

2. Between torsions α and γ (Figure 3.9b), the distributions are trimodal, and there is an overall preference for values of α near 300 ° and γ near 60° that are observed in the majority of both B and A forms. The combination of α near 60° and γ near 300° is observed almost exclusively in DNA/protein complexes. This again demonstrates the broadening of distributions and larger structural diversity of the complexes.

3. Between sugar pucker and glycosidic angle χ, especially for pyrimidine nucleosides (Figure 3.9c), C3’-endo pucker is usually associated with median-value anti glycosidic angles near 200°. This is a typical arrangement observed in the A-form. C2’-endo puckers are commonly found with higher anti % angles, in the range 240-280°, which is typical for the B-form. Syn glycosidic angle conformations show a marked preference for C2 -endo sugar puckers.

Further analysis of nucleic acid conformations in RNA structures has led to the identification of about 50 discrete RNA dinucleotide conformers (Richardson et al., 2008). These have been compiled in a library of consensus conformations that can be useful for finding motifs in RNA and for the modeling of experimental electron densities.

STRUCTURES OF NUCLEIC ACIDS

DNA Duplexes

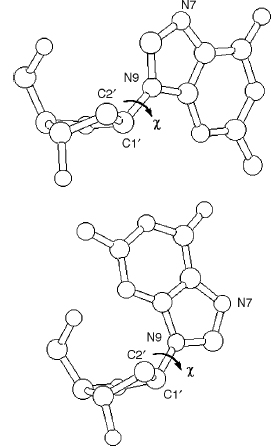

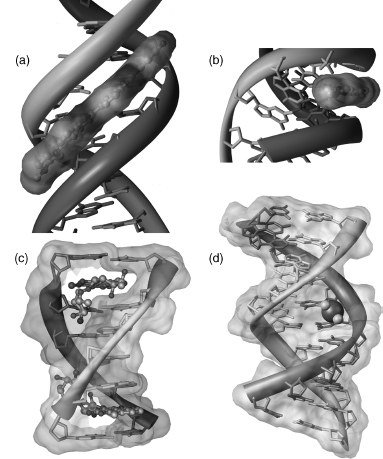

The first known structures of nucleic acids were of DNA duplexes derived using fiber diffraction methods. B-DNA, the classic structure first described by Watson and Crick (Watson et al., 1953), has been refined using the linked-atom least-squares procedure developed by Arnott and his group (Kim et al., 1973). In canonical B-DNA (Figure 3.10), the backbone conformation has C2’-endo sugar puckers and high anti glycosidic angles (—100°). The right-handed double helix has 10 base pairs per complete turn, with the two polynucleotide chains antiparallel to each other and linked by Watson-Crick AT and GC base pairs. The paired bases are almost exactly perpendicular to the helix axis, and they are stacked over the axis itself. Consequently, the base-pair separation is the same as the helical rise, that is, —3.4 Å. An important consequence of the Watson-Crick base-pairing arrangement is that the two deoxyribose sugars linked to the bases of an individual pair are asymmetrically on the same side of it. So, when successive base pairs are stacked on each other in the helix, the gap between these sugars forms two continuous indentations with different dimensions in the surface that wind along, parallel to the sugar-phosphodiester chains. These indentations are termed grooves. The asymmetry in the base pairs results in two parallel types of groove, whose dimensions (especially their depths) are related to the distances of base pairs from the axis of the helix and their orientation with respect to the axis. The wide major groove is almost identical in depth to the much narrower minor groove that has the hydrophobic hydrogen atoms of the sugar groups forming its walls. In general, the major groove is richer in base substituents O6, N6 of purines and N4, O4 of pyrimidines compared to the minor groove (Figure 3.3). This, together with the steric differences between the two, has important consequences for interaction with other molecules.

Figure 3.10. A-, B-, and Z-DNA double helices in the canonical conformations. All helices are formed by 22 base pairs.

Over 200 single-crystal structures with B-DNA conformations have been determined since the first such structure was published (Figure 3.11a) (Drew et al., 1981). The average values of the base morphology parameters are close to the canonical values derived from fiber studies. However, the individual structures have diverse shapes. Many uncomplexed DNA structures are bent by as much as 15° (Dickerson, Goodsell, and Kopka, 1996), and the groove widths are variable (Heinemann, Alings, and Hahn, 1994). The bending is a function of some of the base morphology parameters, in particular twist and roll. Attempts to relate the base morphology parameters to the sequence of the bases have shown some trends. Twist and roll appear to be correlated with regressions that depend on the nature of the bases in the step; purine-pyrimidine, purine-purine, and pyrimidine-purine steps show distinctive differences (Quintana et al., 1992; Gorin, Zhurkin, and Olson, 1995). AT base pairs in AA steps have high propeller twist and bifurcated hydrogen bonds (Yanagi, Prive, and Dickerson, 1991). Stretches of A in sequences appear to be straight (Young et al., 1995). On the contrary, certain steps such as TA and CA show a very large variability due to crystal packing, sequence context, or both (Lipanov et al., 1993). This is consistent with the findings of a combined NMR and low-angle X-ray analysis (Schwieters and Clore, 2007), which has also provided reliable solution data on the amplitudes of motion for BI/BII phosphate exchanges, sugar pucker, and base morphology.

Figure 3.11. Important structural forms of DNA. Molecules are colored by strand. (a) B-DNA dodecamer (Drew et al., 1981); (b) A-DNA octamer (McCall et al., 1985); (c) Z-DNA hexamer (Gessner et al., 1989 ; Frederick et al., 1990); (d) DNA guanine tetraplex. Four guanine tetramers are flanked bytwoT-T-T-T loops, potassium cations are shownin magenta(Haider, Parkinson,andNeidle, 2002); (e) cytosine tetraplex, or i-motif (Chen et al., 1994). In (a), (b), and (c), two perpendicular views are shown. The minor groove is shown in the red line. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

A novel host-guest approach has been used to analyze DNA sequences that are unable to crystallize on their own (Cote, Yohannan, and Georgiadis, 2000). This uses the N-terminal fragment of the Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase as a sequence-neutral “host” to bind to a wide range of 16-mer DNA sequences, including ones with mismatches and bound drug molecules. The resulting structures have a dumbbell-like appearance with a protein molecule at each end connected by the oligonucleotide duplex. There is sufficient flexibility in the DNA such that sequence-dependent effects are apparent. For example, a study of the sequence d(CTTTTTAAAAGAAAAG) with its complementary strand has shown that in spite of there being three A tracts in the sequence, the structure overall is not significantly bent (Cote, Pflomm, and Georgiadas, 2003).

Included among the many B-DNA structures are numbers with base mispairs. Interestingly, these mutations cause only local perturbations to the structures, and the overall conformations of these structures remain the same as the parent structures.

Hydration also plays an important role in the structure of B-DNA. The spine of hydration first seen in the dodecamer structure and described in some detail (Dickerson et al., 1983) has proven to be an enduring feature of these molecules. A detailed analysis of the hydration around the bases in DNA has demonstrated that the hydration is local (Schneider and Berman, 1995). Hydrated building blocks from decameric B-DNA were used to construct the dodecamer structure and the spine was faithfully reproduced. That same analysis strongly suggests that the patterns of hydration, be they spines or ribbons, are a function of the base morphology and that there is strong synergy between the hydration and base conformations.

Canonical A-DNA (Figure 3.10) has C3’-endo sugar puckers, which bring consecutive phosphate groups on the nucleotide chains closer together at 5.9 Å, compared to the 7.0 Å in B-form DNA (Figure 3.2). This alters the glycosidic angle from high anti to anti.As a consequence, the base pairs are twisted and tilted with respect to the helix axis and are displaced nearly 5 Afrom it, in striking contrast to the B-helix. As a consequence, the helical rise is much reduced to 2.56 Å, compared to 3.4 Å for canonical B-DNA. The helix is wider than the B form and has an 11 base-pair helical repeat. The combination of base-pair tilt with respect to the helix axis and base-pair displacement from the axis results in very different groove characteristics for the A double helix compared to the B form. This also results in the center of the A double helix being a hollow cylinder. The major groove is now deep and narrow, and the minor one is wide and very shallow.

Analysis of the A-DNA crystal structures has shown that there are variations in the helical parameters that appearto be related to crystal packing (Ramakrishnan and Sundaralingam, 1993). Two sequences have been found to crystallize in two different space groups—GTGTACAC (Jain, Zon, and Sundaralingam, 1989; Jain, Zon, and Sundaralingam, 1991; Thota et al., 1993) and GGGCGCCC (Shakked et al., 1989). In both cases, the helical parameters are different in different crystal forms. Another analysis of a series of A-DNA duplexes shows that there is an inverse linear relationship between the crystal packing density and the depth of the major groove (Heinemann, 1991).

In the earlier days of nucleic acid crystallography, it had been thought by some that the A conformation was simply a crystalline artifact and not likely to bear any relationship to biology. Now it has been demonstrated that in the TATA binding protein-DNA complex (Kim, Nikolov, and Burley, 1993; Kim et al., 1993), the conformation of the DNA is an A-B chimera (Guzikevich-Guerstein and Shakked, 1996). The apparent deformability of the base geometry seen in A-DNA oligonucleotide crystal structures may prove to be an advantage in forming protein-DNA complexes. All of this shows the innate plasticity of the DNA duplex, a view reinforced by studies that show DNA in transition from A to B helices. Thus, the crystal structures of six d(GGCGCC) duplex hexanucleotides with varying degrees of cytosine bromination or methylation (Vargason, Henderson, and Ho, 2001; Ng and Dickerson, 2001) show features that progressively span A, B, and plausible intermediate states.

One of the earliest determined A-type structures demonstrated a unique arrangement of water molecules consisting of edge-linked pentagons (Shakked et al., 1983). This pattern, like the spine seen in B-DNA, provoked the continued pursuit of the role of hydration in the stabilization of the different forms of DNA. One theory is that the “economy of hydration” seen in A-type structures may provide a structural explanation for the B to A transition as the humidity is lowered (Saenger et al., 1986). In a study of the hydration of a series of A-DNA structures, it was demonstrated that the bases have specific patterns and that both the direct and the water-mediated interactions could be related to recognition properties of DNA and proteins (Eisenstein and Shakked, 1995).

Around the same time that the single-crystal structure of B-DNA was determined, a left-handed conformation called Z-DNA was discovered (Wang et al., 1979). The zigzag phosphate backbone defines a convex outer surface of the major groove and a deep central minor groove (Figures 3.10 and 3.11c). Z-type structures have alternation of cytosine and guanine with a cytosine at the first position. Of the unmodified Z-DNA structures, there are very few examples in which there have been substitutions of A for G and T for C. Modifications of the cytosines with methyl groups at the five positions have allowed for more drastic sequence changes as exemplified by a structure with tandem G’s in the center (Schroth, Kagawa, and Ho, 1993) and another with an AT at that position (Wang etal., 1985). A B-Z junction has been observed in the crystal structure (Ha et al., 2005) of a 15-base-pair sequence containing within it a CG hexanucleotide Z-DNA motif. This was tethered by being bound to domains of a Z-DNA binding protein, so that eight base pairs are in the Z-form and six are in a B-DNA conformation. There is a sharp B-Z backbone turn at the junction and the resulting B-helix is of a standard regular conformation.

The basic building block of Z-DNA is a dinucleotide with the twist of the CG steps 9° and of the GC steps 50°. The backbone conformation of χ-DNA is characterized by the alternation of the % angle of the guanine and the cytosine, where the former is syn and the latter anti. The values for backbone torsion angles do not resemble those found in either A- or B-DNA. In many Z-DNA crystals, the central step of one chain has a different conformation than the other steps. This conformational polymorphism is called ZI and ZII (Gessner et al., 1989). Analysis of the packing patterns in Z crystals has shown that it is possible to correlate the pattern of water bridges with the presence of the ZI-ZII pattern (Schneider et al., 1992).

The hydration characteristics of Z-DNA crystals are very uniform with a spine of hydration in the central minor groove and tightly bound water on the exterior major groove (Gessner et al., 1994). The effects of solvent reorganization as a result of subtle sequence changes have been offered as a very plausible explanation for the different stabilities of these sequences (Wang et al., 1984; Kagawa et al., 1989).

Drug Complexes in Double Helical DNA

Three major types of drug interactions have been observed. The intercalation mode was first observed in a cocrystal between UpA and ethidium bromide (Tsai et al., 1975) and in a subsequent series of dinucleoside drug complexes (Berman and Young, 1981). The first known intercalation complexes (Wang et al., 1987) with longer stretches contained daunorubicin sandwiched between the terminal CG base pair. Now more than 200 related structures have been determined, thus shedding light on the effects of changes on the drug and the sequence. The determination of the structure of a complex between actinomycin D (Kamitori and Takusagawa, 1994) and an octamer in which the drug is bound to the central GC base pair showed how the double helix can accommodate the drug without itself fraying. Among the large number of intercalation complex crystal structures are several with rhodium-containing molecules. These have been remarkable in showing the consequences of intercalation in longer DNA sequences. The crystal structure (Kielkopf et al., 2000) of a rhodium complex intercalated into an octanucleotide duplex has five independent complex molecules in the crystallographic asymmetric unit. They all show consistent structural features and conformations, with the planar group inserted from the major groove direction and embedded at the center of a significant length of DNA sequence, thus showing the molecular features of intercalation that are relevant to the situation in bulk DNA. A rhodium complex has also been cocrystallized (Pierre, Kaiser, and Barton, 2007) with a mismatched dodecamer d(CGGAAATTCCCG).

The second class of drug complexes involves a drug bound in the minor groove of a B-type helix. Starting with the determination of the structure of netropsin bound to the Dickerson dodecamer (Kopka et al., 1985), there have been over 50 determined structures in which the drugs bind to the minor groove (Figure 3.12a). Several of these contain the Hoechst benzimidazole derivative, which is typical for these structures in having a planar hetero-aromatic cross section whose dimensions complement those of the A/T narrow minor groove. In general, these groove binders show strong sequence specificity that is moderated by a combination of hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions (Tabernero, Bella, and Aleman, 1996). There are examples in this class of complexes in which two drugs are bound in a side-by-side manner in the minor groove of an octameric fragment of DNA (Chen et al., 1994). Many of these molecules have a crescent-like shape that complements the curvature of the minor groove. However, this is not a universal requirement, as has been shown by several crystal structures and associated biophysical studies of linear or near-linear molecules that bind strongly in the minor groove. The crystal structure of the almost linear meta-substituted diamidine molecule CGP40215A with d(CGCGAATTCGCG)2 shows it binding in the minor groove A/T region (Nguyen et al., 2002) and has short water-mediated contacts with base edges.

Figure 3.12. Double-helical DNA interacting with drug molecules. (a) and (b) Drug Hoechst 33258 binding to the minor groove of B-DNA (Quintana et al., 1992). (b) Shows the fit of flat drug molecule into the minor groove; (c) drug daunomycin intercalated between base pairs of B-DNA octamer CGATCG (Moore et al., 1989); (d) cis platinum covalently bound to guanine bases. Pt is shown as a large sphere with theNH2groups pointing to the viewer. Two Pt_N7(G) bonds (point into the paper plane) bend DNA double helix (Takahara et al., 1995).

Although covalent adducts are thought to be key in carcinogenesis as well as antitumor activity, in general, it has been very difficult to obtain crystalline samples. There are some examples, such as an anthramycin molecule bound to a dodecamer (Kopka et al., 1994) and several complexes of platinum-containing drugs (see, for example, Silverman et al., 2002). Most of the carcinogenic adducts that have been crystallized are simple modifications to the O6 methyl group of G. Two structures containing this type of modification are crystallized in the same approximate unit cell as the parent dodecamer but are not isomorphous (Gao et al., 1993; Vojtechovsky et al., 1995). This may demonstrate how a local lesion may actually affect interaction and recognition properties. A pharmaceutically important structure is that of the antitumor agent cis platinum covalently bound to tandem guanine residues in a DNA duplex. The DNA is strongly bent as a result of this interaction (Takahara et al., 1995) (Figure 3.12d). In addition, several of the complexes containing daunomycin are actually covalent adducts that were formed from the presence of formaldehyde in the crystallization drop (Wang et al., 1991).

DNA Quadruplexes

The existence of a tetrameric arrangement of DNA and RNA helices was first shown in fiber of polyG and polyI (Gellert, Lipsett, and Davies, 1962; Arnott, Chandrasekharan, and Marttila, 1974). Their biological relevance was discovered later when it was hypothesized that these types of conformations may occur in telomeres (Sen and Gilbert, 1988; Rhodes and Giraldo, 1995). Guanine-rich DNA sequences can form multistranded structures as a consequence of the ability of guanine bases to form planar hydrogen-bonded arrays simultaneously involving two of its faces, notably the guanine (G) quartet formed with four guanine bases. The resulting structures can be formed from one, two, or four strands to form fold-back intramolecular, bimolecular or tetramolecular structures, respectively. All require the presence of centrally coordinated potassium, sodium, or similarly sized cations for stability. These structures, termed quadruplexes, have considerable diversity that depends on the number of separate strands involved, on the relative polarities of the strands, and on the intervening nonguanine loop sequences. There are now several examples of crystal structures of quadruplex DNA: d(TGGGGT) forms a tetramolecular quadruplex (Phillips et al., 1997), d(GGGGTTTTGGGG) forms abimolecular one (Haider, Parkinson, and Neidle, 2003), and d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] forms a parallel-stranded intramolecular quadruplex (Parkinson, Lee, and Neidle, 2002). Figure 3.11d shows an example of one such crystal structure.

G-quadruplexes may provide target locations for selective therapeutic action, for example, at the ends of telomeres in human cancer cells, where telomere maintenance is fundamentally distinct from that in normal cells. A few crystal structures of drug complexes are available that are useful in structure-based design studies. All show planar drug molecules stacked onto the terminal G-quartets of quadruplexes and not intercalated within the structure (Haider, Parkinson, and Neidle, 2003; Parkinson, Ghosh, and Neidle, 2007), in accordance with observations that quadruplexes are stable structures that cannot be as readily disrupted by small molecules such as duplex DNA.

In the last few years, there has been a pronounced increase in the number of RNA structures determined. This is due in part to the improved ability to obtain pure material and crystallize it (Wyatt, Christain, and Puglisi, 1991; Wahl et al., 1996). Although RNA is generally single stranded, double-stranded RNA can be readily formed, analogous to duplex DNA. Uracil participates in UA base pairs that are fully isomorphous with A T pairs in duplex DNA. Duplex RNA is conformationally rather rigid, and its behavior contrasts remarkably with the polymorphism of duplex DNA in that only one major polymorph of the RNA double helix has been observed. This has many features in common with A-DNA and, accordingly, is known as A-RNA. The conformational features of canonical RNA helices have been obtained from fiber diffraction studies on duplex RNA polynucleotides from both viral and synthetic origins. A-RNA is an 11 -fold helix, with a narrow and deep major groove and a wide, shallow minor groove, and base pairs inclined to and displaced from the helix axis. A-RNA helices have the C3’-endo sugar pucker. Another way it differs from duplex DNA is that RNA helices, though capable of a small degree of bending (up to ca. 15°), do not undergo the large-scale bending seen, for example, in A-tract DNA.

A number of structures of base-paired duplex RNA have been reported, the first being the structures of r(AU) and r(GC) (Rosenberg et al., 1976; Seeman et al., 1976). Crystallo-graphic analyses of sequences, such as the octanucleotide r(CCCCGGGG), have shown helices of length sufficient for a full set of helical parameters to be extracted. This sequence crystallizes in two distinct crystal lattices, enabling the effects of crystal packing factors on structure to be assessed (Portmann, Usman, and Egli, 1995). In each instance, rhombohedral and hexagonal, the RNA helices are very similar, and their features closely resemble those in fiber diffraction canonical A-RNA. The structure of r(UUAUAUAUAUAUAA) was the first to show a full turn of an RNA helix (Dock-Bregeon et al., 1989). Again, the helix is essentially classical A-RNA.

The increasing availability of high-resolution crystal structures has enabled RNA hydration in oligonucleotides to be defined. Some general rules are beginning to emerge for the water arrangements beyond the obvious finding of an inherently greater degree of hydration compared to DNA oligonucleotides, because the 2 -OH group is an active hydrogen bond participant. There is no analogue of the minor groove spine of hydration seen in B-DNA. Again, this is unsurprising since the minor groove in A-RNA is too wide for such an arrangement.

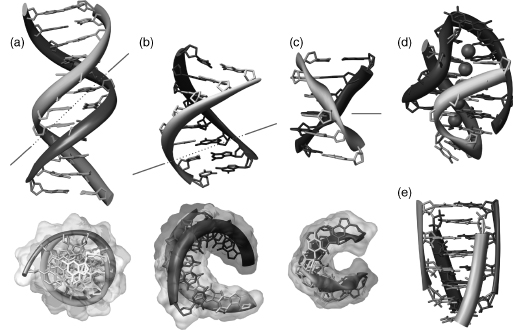

Mismatched and Bulged RNA

RNAs can readily form stable base pair and triplet mismatches and extrahelical regions within the context of “normal” RNA double helices. Such features, notably extrahelical loops, have been the subject of intense structural study, since they are present in large RNAs (tRNA, mRNA, rRNA) and, together with various types of base stacking, are responsible for maintaining their tertiary structures. It is paradoxically common for crystal structures of short sequences containing potential loop regions, such as the UUCG “tetraloop” (an especially stable extrahelical loop structure in solution), not to show such features. This is probably a consequence of the high ionic strength of many crystallization conditions, together with the preference of some sequences to pack in the crystal as helical arrays. So, instead of loops, these crystal structures tend to have runs of non-Watson-Crick mismatched base pairs where the loop would have formed. For example, an A-RNA double helix, albeit with GU and UU base pairs, is formed in the crystal by the sequence r(GCUUCGGC) d(BrU) (Cruse et al., 1994). There is evidence of some deviations from the exact canonical A-RNA duplexes formed by fully Watson-Crick base pairs, since this helix has <10 base pairs per turn. The dodecamer sequence r(GGACUUCGGUCC) (Figure 3.13a) similarly forms a base-paired duplex (Holbrook et al., 1991), withUC and GU base pairs. The A-RNA helix here has a significant increase in the width of its major groove, possibly on account of the water molecules that are strongly associated with the mismatch base pairs. Much greater perturbations are apparent in the structure of the dodecamer r(GGCCGAAAGGCC) (Baeyens et al., 1996), where the four non-Watson-Crick base pairs in the center of the sequence form an internal loop with sheared GA and AA base pairs. The resulting structure is very distorted from A-RNA ideality, with a compression of the major groove, an enlargement of the minor groove width to 13.5 Å, and a pronounced curvature of the resulting helix. This sequence forms a tetraloop in solution (Baeyens et al., 1996). The GU base pair is a prominent and very important element of large RNA structures since it is especially stable (Varani and McClain, 2000) because of its two hydrogen bonds. It is known as the “wobble” pair, since a G in the first position of a codon can accept either a C or a U in the third anticodon (wobble) position.

Figure 3.13. Examples of RNA molecules: (a) A-RNA dodecamer with non-Watson–Crick base pairs in the double helix (Holbrook et al., 1991); (b) phenylalanine transfer RNA (Sussman et al., 1978; Brown et al., 1985); (c) group I intron ribozyme (Cate et al., 1996); (d) Hammerhead ribozyme. The shorter strand is the DNA inhibiting the catalyzed reaction (Pley, Flaherty, and McKay, 1994); (e) guanine riboswitch (Batey, Gilbert, and Montange, 2004). Hypoxanthine bound in the active site is shown in yellow (Please see figure at supplementary weblink).

This tendency of short RNA sequences to maximize helical features is also apparent in the crystal structure of a 29-nucleotide fragment from the signal recognition particle (Wild et al., 1999) that forms 28-mer heteroduplexes rather than a hairpin structure. Even so, this duplex has features of wider interest, since it has a number of non-Watson-Crick base pairs such as a 5’ -GGAG/3’ -GGAG purine bulge. Their overall effect is to produce backbone distortions so that the helix has non-A-RNA features such as a widening of the major groove by ~9A and local undertwisting of base pairs adjacent to AC and G-U mismatches.

In this respect, the structural studies of Dumas and Ennifar of the HIV-1 retrovirus dimerization initiation site (DIS) are of great interest. DIS has features that act as signals for RNA packaging and subsequent virulence and are known to contain nonhelical motifs, some of which have been studied by structural methods. In their early studies, the expected secondary structure with two loops in a “kissing-loop” (loop-loop) arrangement was not observed. Instead, the crystal contains duplex with two AG base pairs, each adjacent to an extrahelical, bulged-out adenosine (Ennifar et al., 1999). However, more recent studies with crystals grown under different conditions revealed the expected arrangement of the “kissing loops” between recognition loops (Ennifar and Dumas, 2006), in agreement with an NMR study (Baba et al., 2005).

Transfer RNA

The crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA (Figure 3.13b) was determined in the early 1970s simultaneously by two groups (Kim etal., 1974; Robertusetal., 1974). Together with a few other tRNAs, these structures remained the sole complex RNA molecular structures available for 20 years until the first ribozyme structure was determined. The structures—one monoclinic (Robertus et al., 1974) and the other orthorhombic (Kim et al., 1974)—are similar. They showed that the molecule is folded into an overall L-shape, with two arms at right angles to each other. The original cloverleaf is still apparent, but with additional interactions between distant parts of the structure. The arms consist of short A-RNA helices with extensive base-base interactions that hold the two arms together. The longer double helical anticodon arm has the short helix of the D stem stacked upon it. The other arm is formed by the helix of the acceptor stem, on which is stacked the four base-pair T arm helix. This key feature of helix-helix stacking has turned out to be of central importance for other complex RNAs. The nine additional base…base interactions that maintain the structural fold all tend to be in the elbow region, where the two arms are joined together. Almost all of these are of non-Watson-Crick type, and several are triplet interactions. Other subsequent crystal structures of tRNAs have shown that the overall L shape is invariant, as are many of the tertiary interactions.

Ribozymes

The ability of certain RNA molecules to catalyze chemical reactions, in most cases self-cleavage or cleavage of other RNA molecules, is one of the most convincing pieces of evidence suggesting the existence of an “RNA world” (Gilbert, 1986;Gesteland, Cech, and Atkins, 1999). Several distinct categories of RNA enzymes, called ribozymes, are known to date, with undoubtedly more remaining to be discovered:

- The RNA of self-splicing group I introns from Tetrahymena was the first ribozyme to be discovered (Cech, Zaug, and Grabowski, 1981). To date, there are over a thousand in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms. These ribozymes contain four conserved sequence elements and form a characteristic secondary structure (Cate et al., 1996) (Figure 3.13c). The initial step of the cleavage involves a nucleophilic attack by a conserved guanosine.

- The RNA of self-splicing group II introns also have conserved sequence elements, but have a very different secondary and tertiary structure (Zhang and Doudna, 2002). These structures have a distinct mechanism of cleavage that involves the nucleophilic attack of a conserved adenosine, contained within the intron sequence.

- The RNA subunit of the enzyme, ribonuclease P, is a protein-assisted ribozyme that is conserved in all kingdoms of life and exists in at least two forms (Krasilnikov et al., 2003, 2004).

- Self-cleaving RNAs from viral and plant satellite are smaller than the group I or II intron ribozymes and include the hammerhead ribozyme. The crystal structures of hammerhead ribozymes were the first to be determined (Figure 3.13d). One is of a complex with a DNA strand containing the putative cleavage site (Pley et al., 1994); since ribozymes do not cleave DNA, this is effectively an inhibitor complex. The structure shows three A-RNA stems connected to a central two-domain region encompassing the catalytic core that contains the conserved residues.

- Hairpin ribozymes are another group of self-cleaving RNAs from viral and plant satellite RNAs. Their structures consist of two parallel double helices, one with a bulge forming the catalytic active site (Salter et al., 2006). The glmS ribozyme is currently the only natural ribozyme requiring a small-molecule cofactor for catalysis and can therefore be considered a riboswitch (Klein and Ferre-D’Amare, 2006).

- Structures of other types of ribozymes, such as the hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme (Ferre-D’Amare, Zhou, and Doudna, 1998), or ribozyme fragments, such as the five catalytic helical segments from the Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme (Campbell and Legault, 2005), have also been determined.

- Ribosomal RNA is responsible for synthesis of peptide bonds in newly synthesized proteins (discussed below).

RNA Involved in Posttranscriptional Gene Control

RNA molecules have been shown to actively participate in posttranslational control of gene expression. Their involvement includes splicing of pre-mRNA, gene silencing by RNA interference, and control of RNA turnover by riboswitches.

RNA interference (RNAi) is a mechanism of the posttranscriptional inhibition of gene expression called “gene silencing.” It involves microRNA (miRNA), which are single-stranded RNA of about 20-25 nucleotides in length that bind to their target mRNA to form double-stranded RNA that are then recognized and cut by a specific RNase III, dicer (Macrae et al., 2006) into short double-stranded RNA segments with dinucleotide overhangs

(siRNAs).

The mechanism of RNAi highlights a functional role for double-stranded RNA. The PAZ domain, for example, is an RNA binding domain from the human Argonaute protein that in complex with a nona-nucleotide siRNA-like double helix (Ma, Ye, and Patel, 2004) shows sequence-independent protein binding to the heptameric A-RNA double helix with a 3’-end dinucleotide overhang on both strands.

Riboswitches are noncoding (pre-)mRNA sequences found at their 5’ untranslated end that interact with small-molecule ligands and interfere with expression of the genes involved in metabolism of these ligands. These single-stranded RNA molecules act without protein assistance. Riboswitches include oligonucleotide domains that are capable of conforma-tional changes induced by binding of their ligand and downstream regions that contain expression-controlling elements.

One example is seen in the crystal structure of the adenine binding riboswitch that distinguishes between bound adenine and guanine with high specificity. It has two parallel double helices wrapped around each other and connected by three hairpin loops; the 5’ - and 3’-end sequences form the third double helix (Serganov et al., 2004). The internal bulges zipper up to form the purine binding pocket. The structure of the guanine riboswitch from a different organism (Figure 3.13e) (Batey, Gilbert, and Montange, 2004) shows very similar architecture. Also, other known structures of riboswitches show similar architecture suggesting its general relevance.

The Ribosome

The ribosome is responsible for protein synthesis in all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. It consists of two subunits, each a complex of proteins and ribosomal RNA. The complete 70S prokaryotic ribosome has a total molecular weight of about 2.5 million daltons. In prokaryotes, the 30S subunit contains about 20 proteins and a single RNA molecule of around 1500 nucleotides in length. The larger 50S subunit contains half as many more proteins and a large RNA of about 3000 nucleotides, together with the small (120 nucleotide) 5S RNA. The primary function of the small subunit is to control tRNA interactions with mRNAs. The large subunit controls peptide transfer and undertakes the catalytic function of peptide bond formation.

Structural studies on bacterial ribosomes have been underway for almost 40 years, with the ultimate goal of achieving atomic resolution to understand the mechanics of ribosome function. In the last few years, several groups have successfully determined the structures of ribosomal subunits as well as the whole ribosome (Ban et al., 2000; Schluenzen et al., 2000; Wimberly et al., 2000; Yusupov et al., 2001).

The 3.0Å crystal structure of the 30S subunit has the complete 16S ribosomal RNA of 1511 nucleotides together with the ordered regions of 20 ribosomal proteins, organized into four well-defined domains. The implication is that there is considerable flexibility between them, which is needed to ensure the movement of messenger and transfer RNAs. The overall shape of the 30S particle is dominated by the structure of the folded RNA. The secondary structure of the RNA shows over 50 helical regions. The numerous loops are mostly small and do not disrupt the runs of helix in which they are embedded. There are extensive interactions between helices, mostly involving coaxial stacking via the minor grooves. In one type of helix-helix interaction, two minor grooves abut each other with consequent distortions from A-type geometry. These distortions, which tend to involve runs ofadenines, are facilitated by both extrahelical bulges and noncanonical base pairs as similarly observed in simple RNA structures. Less commonly, the perpendicular packing of one helix against another, also via the minor groove, is mediated by an unpaired purine base. This mode is of special importance since it involves the functionally significant helices in the 30S subunit. The motifs of RNA tertiary structure such as non-Watson-Crick base pairs, base triplets and tetraloops, all contribute to the overall structure.

The majority of the 20 proteins in the ribosomal structure each consist of a globular region and a long flexible arm. The latter has been too flexible to be observed in structural studies on the individual proteins but has been located in the 30S subunit, where it plays an important role in helping to stabilize the RNA folding by essentially filling the numerous spaces in the RNA folds.

The structure identifies the three sites where tRNA molecules bind and function and where the essential proofreading checks for fidelity of code reading and translation occur. These sites are the P (peptidylation) site, where a tRNA anticodon base pairs with the appropriate codon in mRNA and where the peptide chain is covalently linked to a tRNA; the A (acceptor) site, where peptide bonds are eventually formed (the actual peptidyl transferase steps occur in the 50S subunit); and the E (exit) site, where tRNAs are released from the subunit as part of the protein synthesis cycle.

tRNA itself is not present in this crystal structure, but the RNA from a symmetry-related 30S subunit effectively serves to mimic it as the anticodon stem loop. Its interactions with the 30S RNA are also mediated via (1) minor groove surfaces, helped by some contacts with ribosomal proteins and (2) backbone contacts. Interestingly, the exit site of the tRNA is almost exclusively protein associated, whereas the other functional sites are composed of RNA and not protein. It is thus the ribosomal RNA that mediates the functions of the 30S subunit and not the ribosomal proteins.

In the 2.4Å crystal structure of the 50S subunit, 2711 out of a total of 2923 ribosomal RNA nucleotides have been observed, together with 27 ribosomal proteins, and 122 nucleotides of 5S RNA, with the subunit being about 250 A in each dimension. Although the RNA itself can be arranged into six domains on the basis of its secondary structure, overall the 50S subunit is remarkably globular, reflecting its greater conformational rigidity compared to the 30S subunit, consistent with its functional need to be more flexible.

The first determined structure of the complete bacterial 70S ribosome (Yusupov et al., 2001) revealed much about the interactions between the subunits that are an essential element to the protein synthesis cycle. More recently, higher resolution structures (Berk et al., 2006; Korostelev et al., 2006; Selmer et al., 2006) (Figure 3.14) have provided more detailed information about the mechanisms of recognition between tRNA and its three ribosomal recognition sites, A, P, and E, and about the assembly between the 30S and 50S subunits.

Functionally variable RNA molecules are an important target for drugs; bacterial ribosomes are targeted by many clinically important antibiotics. With the determination of ribosomal crystal structures, information about the structural details of their interactions with different drugs has become abundant (Hermann, 2005), thus shedding light on structural details of translational machinery as well as giving hints for the discovery of new antibiotics.

Figure 3.14 The structure of the complete 70s ribosome (Selmer et al., 2006). The 30S subunit is on top, the 50S is on the bottom. RNA molecules are rendered as surfaces: yellow for 16S rRNA, light blue for 23S rRNA, blue for 5S rRNA, and red for the three tRNA molecules. Proteins are shown as helix/turn cartoons in orange and pink for the small and large subunits, respectively. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

The ribosome can be targeted at different subsites by chemically diverse molecules. For example, aminoglycoside antibiotics binding at the decoding site of the 16S rRNA (A-site) in the small ribosomal subunit compromises the fidelity of protein synthesis of the targeted bacteria. Structures of complexes between the small subunit and clinically important drugs such as tetracyclines (Brodersen et al., 2000) or paromomycin (Carter et al., 2000) are known. Quite significantly, key structural features of drug/RNA interactions in these large ribosome-drug complexes are preserved at the oligonucleotide level in both solution (Fourmy et al., 1996) and crystal structures (Vicens and Westhof, 2001), opening a way to use these smaller systems for drug design.

Some of the most clinically important antibiotics, for example, macrolides, stepto-gramins, chloramphenicol, and oxazolidones block the peptidyl-transferase catalytic site and/or peptide exit tunnel in the 23S rRNA of the large ribosomal subunit (Harms et al., 2003). Extensive structural studies of ribosome inhibition by these drugs (Hansen et al., 2002; Schlunzen et al., 2003; Tu et al., 2005) have revealed structural details about their binding inside the peptide exit tunnel of the 23S rRNA. Molecular details of the inhibition will be extremely useful in the design of new potent and specific drugs.

CONCLUSION

The past 20 years has seen an exponential growth in the determinations of nucleic acid structures. DNA crystallography has provided information about sequence effects, fine structures, and hydration. RNA crystallography has revealed a rich assortment ofstructural motifs whose characteristics are now under study.

Continued efforts to uncover the underlying principles of nucleic acid structure will result in much greater insights into the complex functions of these molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The 3D molecular images were created using program Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004).BS is supported by a grant LC512 from the Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic.

Funds from the NSF for the NDB is gratefully acknowledged.