31

FOLD RECOGNITION METHODS

INTRODUCTION

Despite a good qualitative understanding of the forces that shape the folding process, present knowledge is not enough to be used for direct prediction of protein structure from first principles, such as the fundamental equations of physics. A related but easier problem is to recognize which of the known protein folds is likely to be similar to the (unknown) fold of a new protein when only its amino acid sequence is known. This has been variously called an inverse folding problem (find a sequence fitting a structure), threading (since a sequence is being threaded through a known structure), and finally a fold recognition problem. Solution of the fold recognition problem is a necessary prerequisite to the solution of the general folding problem. If we are unable to recognize a structure similar to the correct one, how could we possibly arrive at the correct structure starting for a random one? At the same time, even the partial solution to the fold recognition problem offers the immediate advantage of an efficient and fast structure prediction tool.

Such considerations lead to the development of methods, which attempt to recognize possible structural similarities even in the absence of recognizable sequence similarity. Of course, advances in sequence analysis are constantly changing the threshold between fold recognition and sequence-based homology recognition. Therefore, in this contribution, both sequence and structure/energy-based fold recognition methods will be discussed together.

The practical importance of the fold recognition approach to protein structure prediction stems from the fact that very often apparently unrelated proteins adopt similar folds. As discussed elsewhere in this book, more than half of the newly solved proteins thought to be unrelated to any of the known proteins turn out to have a well-known fold. Only a few years ago, such cases were viewed as a curiosity, but now they become almost a rule. Some folds such as a beta barrel TIM fold, were discovered in over 20 protein superfamilies thought to be unrelated. Other popular folds often found in apparently unrelated protein families are Greek-key beta barrels, which are found in immunoglobulins, copper binding proteins, several families of receptors, adhesion molecules, and so on. Similarly, the ferrodoxin fold is present in 36 superfamilies (SCOP, 1995). Overall, only 100 folds account for about half of all protein superfamilies in one of the more popular protein structure classifications, the SCOP database (discussed in detail in Chapter 12). There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon and it is almost certain that some examples may be found for each:

Divergent Evolution: Proteins with similar folds are actually related, but our current sequence analysis tools are not sensitive enough to recognize very distant homologies. Several new algorithms, such as PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997), hidden Markov models (HMM) (Bateman et al., 2000), and profile-profile alignment tools (Rychlewski et al., 2000) redefined sequence similarity. Many protein families that were thought to be unrelated a few years ago are now firmly in the distant homology class. With the continuous improvement of such algorithms, we can expect that a majority of cases of “unexplained structural similarity” will eventually be included in this class.

Convergent Evolution: Common functional requirements, such as binding to the same classes of substrates, lead to similar structural solutions. There are very few undisputed examples of convergent evolution and most involve similarities of small subfragments, such as active site residues (serine proteases) or binding patterns (DNA binding proteins).

Limited Number of Folds: Unrelated proteins end up having similar folds because the space of possible folds is small and Nature is simply running out of solutions. Despite strong theoretical arguments (Ptitsyn and Finkelstein, 1980), there are not many examples for such “accidentally” similar structures except for very small proteins, such as three and four helical bundles. In fact, many theoretically predicted arrangements of secondary structure elements (Chothia and Finkelstein, 1990) are still not seen in Nature despite rapid growth of known protein structures.

Misguided Analysis: Apparent structural similarity may result from deficiencies in our analysis tools and not from any actual similarity between protein structures. For instance, SCOP, CATH, and FSSP structure classification agree in only about 60% of cases (Hadley and Jones, 1999). Detection of structural similarity is usually based on empirical criteria, most often on fitting similarity score to an empirical distribution of random similarity scores. Therefore, a false positive is possible when two structures are very different from all other structures, but not really similar. Of course, predicting such similarities is not really feasible, and also not particularly useful.

A correct choice between these possibilities is fundamental because it not only influences our thinking about the protein sequence/structure/function relationship, but also indicates the most efficient structure prediction strategies. Even more important, the first two possibilities suggest that there could be functional similarities between proteins with similar structures, either due to the evolutionary relationship between proteins or due to convergent evolution. This in turn increases the practical importance of fold recognition that can be now viewed not only as a structure prediction, but also a function prediction tool.

Closer analysis suggests that the first mechanism is responsible for most of the known examples of “unexpected” structural similarity. Often the homology was postulated only after a structural similarity was discovered (Taylor, 1986; Russell and Barton, 1992), but later accepted based on other similarities, including similarities in function. The case of the “enolase superfamily” (Babbitt et al., 1995) is particularly interesting because it illustrates the practical importance of establishing a homology relationship between protein families. In this case, distant homology between enolase and mandelate racemase was postulated based on extensive structural similarities between both enzymes, and despite the lack of (then) recognizable sequence similarity and significant differences between their biochemical function. This hypothesis led to the reevaluation of the enzymatic mechanisms of both proteins and the discovery that a crucial step in two different reactions catalyzed by these two proteins is highly similar, involving the abstraction of the a-proton of a carboxylic acid to form an enolic intermediate. This firmly established the homology of both enzymes and added to our understanding of two different enzymatic reactions, opening a new venue in designing inhibitors for both enzymes. At the same time, it made possible the structure and function prediction for several newly discovered enzymes. At the time of this discovery, fold recognition was in its infancy and none of the then available algorithms was able to recognize a homology that distant, now this would be considered a medium difficulty problem.

Our current understanding of the evolution at the molecular level is good enough to describe the process of small changes and adaptations in proteins. This understanding allows us to reliably assess relationships between proteins when their sequences are similar. It also means that in proteins for which reliable evolutionary relationships can be established, functions and structures had no time to diverge dramatically. At the same time, there is no general consensus about how new protein folds and completely new functions have emerged. Consequently, it is not clear how to study relations between proteins when there is no clear similarity between their sequences and only other arguments suggest that they might be related. The confusion extends to the nomenclature used to describe specific cases. Terms such as superfamily, fold family, and so on are used by different groups in different contexts (Doolittle, 1994). Authors variously claim distant evolutionary relationships (Farber and Petsko, 1990), convergent structural evolution (Lesk, 1995), or random similarities (Ptitsyn and Finkelstein, 1980) in seemingly similar cases.

Fold recognition can be successful in each of the first three scenarios discussed above, but it is the first one that makes it particularly useful. Protein structure prediction is rarely a goal in itself and the real questions usually concern possible functions of new proteins. If the predicted fold comes from a homologous (even distant) protein, there is a good chance that some aspects of function could also be conserved. More recent analyses of fold families suggest that usually the arrangement of active site residues, identity of cofactors, and general features of the reaction being catalyzed are often conserved for enzymes sharing the same fold (Todd, Orengo, and Thornton, 2001). The possibility of predicting even some aspects of function for new proteins adds practical importance to fold recognition, despite its humble origins as a poor man version of the protein folding problem.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND FOR FOLD RECOGNITION

Two different perspectives dominate theoretical studies of proteins and as a result, there are two different classes of fold recognition algorithms. Roughly, they could be called biological and physical because to some extent they embody the research philosophies of these two disciplines. A biologist strives to explain the natural world in terms of patterns of evolution. In a tradition that reaches to Aristotle and Carolus Linnaeus, biologists identify, describe, and classify the diversity of life to reveal the patterns of evolution. Following in this spirit, molecular biologists study proteins very much like eighteenth and nineteenth century naturalists studied plant and animal species. Proteins are described and classified into families and analyzed for patterns of mutations at various positions along the sequence. The sequence similarity between proteins from different species forms the basis of molecular phylogenetics, which now rivals traditional morphological phylogenetics in terms of analysis of the relationships between species. It is often extended to study relations between entire processes, such as regulatory networks and metabolic pathways or between sub-populations within species. In contrast, a physicist seeks to explain Nature in terms of fundamental laws, with similarities between systems being just manifestations of the same laws at work. In this spirit, protein structure is seen as a complex shape defined by specific interactions between amino acids along the chain. Different sequences adopting similar folds are viewed as multiple solutions to the same minimization problem and fold recognition problem can be formulated as a constrained minimization where only some points in conformational space are being considered.

There are many problems that are easily understood and studied within one approach. For closely related proteins, it is possible to build reliable evolutionary trees and analyze the relationships between the organisms from which they came without any reference to the fact that these proteins fold to the same structure adopting a free energy minimum in solution. For studying the short-time dynamics of side chain movements in proteins or for predicting the results of a point mutation, we may not care about how this enzyme evolved. But many problems require insights from both perspectives. Why do some proteins have very similar structures and yet perform very different functions? Why do others have similar functions but their structures are different? How to design a good drug that would bind to the target even if the target would undergo a mutation? How can we predict when and how function would diverge between distantly related proteins?

In this contribution, we show how these two views of the protein lead to the development of two distinct classes of fold recognition algorithms. We discuss how the further progress of this and other areas of protein structure prediction relies on successfully merging these two approaches. The first part discusses the molecular evolution of proteins and how understanding of this process lead to the development of more sensitive algorithms for comparison of protein sequences. The second part presents a “physicist” view of the protein world, concentrating on ideas of energy, potentials of mean force, and free energy and describes prediction methods that use this language to recognize a possible fold of a new sequence.

In most of this chapter, we would study questions of similarities and differences between proteins and the question of relations between them. Therefore, the term “homology” will be used only to denote an implied evolutionary relationship between proteins. In contrast, the term “analogy” or “similarity” will be used to describe the similarity between two sequences or structures without implying any relationship between them.

PROTEINS AS SEEN BY A BIOLOGIST

Molecular Evolution, Sequence Similarity, and Protein Homology

Since protein sequences first became available, researchers realized that sequences of homologous proteins from related organisms are very similar. The difference grows with an increasing evolutionary distance between species, which corresponds very well to the known mechanisms of DNA replication and repair. This observation led to the development of sequence alignment methods (Doolittle et al., 1996), which attempt to find an optimal alignment between the sequences of two (or more) proteins being compared. Since homologous proteins by definition evolved from a common ancestor, we expect that a series of mutations, deletions, and insertions lead from the common ancestor to both modern sequences. A list of such elementary steps is equivalent to a unique alignment. When possible homology between two proteins is considered, the null hypothesis is that the two sequences do not come from the common ancestor. The comparison of their sequences should be similar to that of a comparison between two random strings of letters. Therefore, if a larger than random similarity is found, it is generally assumed that such proteins are homologous. This connection is so strong that sequence similarity is de facto used as a synonym of homology, despite the fact that homology is a much stronger concept and the two are not equivalent. At the same time, two proteins may be homologous despite lack of an easily recognizable sequence similarity.

Once the homology is established, we can predict the structure and function of new proteins reasoning by analogy assuming that in evolution at least some aspects of function are conserved. The rule that strong sequence similarity is equivalent to strong structure and function similarity is the only reliable prediction rule discovered so far. The homology modeling discussed in Chapter 25 turned this general rule into a powerful prediction method. Over the past 40 years, the efforts of X-ray crystallographers and, more recently, NMR-spectroscopists yielded thousands of protein structures, and biochemists have characterized tens of thousands of proteins. These proteins, with their sequences and/or structures available in public databases, form a rich source of knowledge that can be used to identify newly sequenced proteins. To apply analogy reasoning, two problems must be solved. First, the similarity must be recognized, which for distant homologues may not be trivial. Second, the detailed alignment, that is, residue-by-residue equivalence table between the two proteins must be constructed. Interestingly, the former problem turns out to be much harder that the first (Jaroszewski, Rychlewski, and Godzik, 2000).

Protein Sequence Analysis

Sequence comparison is a well-developed scientific field (Doolittle et al., 1990; Gribskov and Dereveux, 1991; Waterman, 1995; Doolittle et al., 1996). With rigorous mathematical techniques similar to those in telecommunication signal analysis, two protein sequences are treated as two strings of characters and the similarity between them is compared to that expected by chance between random strings. If it is larger than that expected by chance, common ancestry is assumed and both proteins are identified as homologous, with subsequent assertions concerning their structure and function.

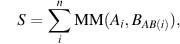

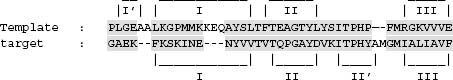

The similarity between two sequence strings is usually defined as the sum of similarities between residues in both proteins at equivalent positions. In the example illustrated in Figure 31.1, identical residues are denoted by vertical bars. A scoring matrix, giving a numerical score for aligning any two amino acids, defines a similarity. The similarity score ranges from large and positive (for the same residue in both positions) to smaller and positive (for residues with similar features, such as valine and leucine) to large and negative (for very different residues). Scoring based on minimizing the difference between two protein sequences is also possible.

(31.1)

Figure 31.1. An example of a sequence alignment between two proteins.

where MM is the mutation matrix and AB(i) is the residue equivalent to i in sequence B. Many different similarity matrices are used in literature with several of the best quite similar to each other despite different assumptions used in their derivation (Frishman and Argos, 1996; Tomii and Kanehisa, 1996). An important feature of the scoring function such as in (Eq. 31.1) is that it is additive or local; in other words, score for one position does not depend on the alignment (or on residues) in another position.

Gaps and insertions in both sequences, such as seen in Figure 31.1, are necessary for the optimal alignment. This is in full agreement with our knowledge of evolution at the molecular level, where mutations as well as deletions and insertions in DNA sequences are possible. The optimal alignment with gaps can be found by dynamic programming (Needelman and Wunsch, 1970; Smith and Waterman, 1981). Alternatively, similar sequences can be identified by searching for high-scoring fragments (HSF) (Altschul et al., 1990), the uninterrupted alignment fragments, presented as highlighted boxes in Figure 31.2. Software tools, such as BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) (now updated to PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997)) or FASTA (Pearson and Miller, 1992) became standards in searching for similar sequences in protein databases and are easily available as software packages (Group, 1991) or Web servers. Other sets of tools, such as CLUSTALW (Higgins and Gibson, 1995) or PileUp (Group, 1991), address questions of organizing a family of homologous proteins into a family tree.

Unfortunately, despite their solid theoretical foundations, all methods and algorithms used in sequence analysis face the same problem. With increasing evolutionary distance, sequence similarity between homologous proteins fades. Using simple alignment tools and mutation matrix scoring, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish the homology from the null hypothesis of random similarity. This is referred to as the “twilight zone” of sequence similarities and corresponds to about 25% of identical amino acids in an optimal alignment between protein pairs. In other words, at the level of about 25% sequence identity, it is equally likely to find a spurious as it is to find a true homology. This value strongly depends on the length of the alignment, as illustrated by well-known examples of identical pentapeptides with different structures (Kabsch and Sander, 1985; Argos, 1987) and analyzed in detail for pairs of similar structures (Sander and Schneider, 1991). Even for whole proteins, there are spurious sequence similarities at such levels. For instance, hypoxantine guanine phosphosibosyltransferase (PDB code 1hmp) and the coat protein of a poliovirus (1piv) share an 80-amino acid fragment with over 40% sequence identity, despite the lack of any structure or function similarity. This and many other examples of spurious similarities around 25% sequence identity illustrate how dangerous it is to assume homology using sequence similarity as the only argument.

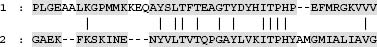

Figure 31.2. A successful example of a fold prediction using a profile-profile alignment program FFAS. A comparison of the predicted and experimental structure of CASP4 target 116 (see the text for the discussion of the CASP experiment). The score of the alignment was statistically significant with the e-value of e-2, despite the very low sequence similarity between the target and the template of 10% identical residues.

In general, homologous proteins that can be reliably identified using simple sequence similarity searches are usually closely related, with little or no variation in function and generally very similar structures.

Protein Families and Multiple Alignments

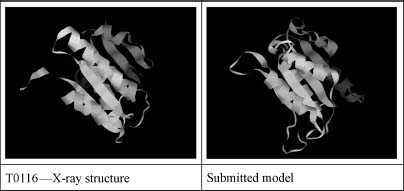

The diversity of sequences in a family of homologous proteins captures successful biological experiments in mutating a protein coding sequence without destroying its function and, what follows, its structure. We can assume that with very few exceptions of pseudogenes or dramatic changes of function between paralogous proteins, the mutations destroying a structure of a protein would not be represented among proteins existing in Nature. Therefore, the analysis of a pattern of mutations in homologous families can provide us with information about the importance of various positions along the sequence and, indirectly, of types of restrictions placed on a given position by the protein function and structure. For instance, we can expect that positions that are easily mutated are not important neither for function nor for structure and are most likely located in exposed loops or turns. In contrast, a position in the hydrophobic core of a protein would easily accommodate only some types of mutations (hydrophob-hydrophob) but not others (hydrophob-hydrophil). In the same way, residues in active sites, on the surface, on the interface between protein domains, all have their own rules, stemming from the fact that similar mutations at different positions would lead to different effects for the entire protein and some would be easily accepted, while others will not. For this reason, a uniform mutation matrix, the same at every position along the sequence does not provide a good description of the evolutionary process under strong pressure of preserving the structure and function of a protein. A set of position-specific mutation rules can be derived from the analysis of a multiple alignment of a homologous family and subsequently used to align new sequences in this family. This idea, in various forms and under different names introduced by several groups (profile, position-specific mutation matrix, or hidden Markov models of protein families), allowed sequence analysis methods to break through the twilight zone and reliably recognize distant homologues even when their sequence identity was much below the 25% identity and comparison of single sequences appeared random.

An entire class of distant homology recognition methods evolved from the analysis of mutation patterns in homologous families. A pattern of sequence variation along the sequence can be used to identify positions where some specific structural and/or functional requirements restrict variation, even without a full understanding of these restrictions. It is important to note that techniques used to recognize protein folds by comparing sequences (or sequence profiles), while often treated as part of fold recognition field, can be also used for more general distant homology recognition problem whether or not the distant homologues have known structure. When applied to fold recognition, these methods explicitly search for proteins from the first of the groups discussed above, the diverging homologous proteins. Distant homology recognition methods closely compete with threading, that is, energy-based fold recognition and in recent years seems to be gaining the upper hand (see later in the chapter) (Figure 31.3).

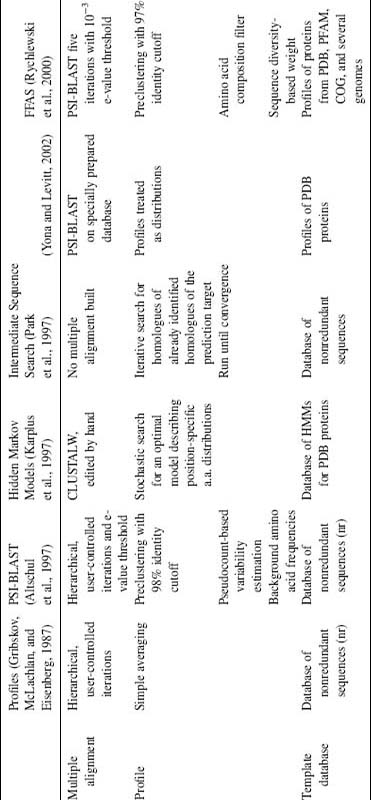

From the time this idea was introduced in 1987 (Gribskov, McLachlan, and Eisenberg, 1987), it remained on the forefront of the sequence analysis field. For instance, several top algorithms in the last CASP4 meeting belong to this category. In recent years, it gained even more popularity as it was implemented in PSI-BLAST, the newest variant of the most popular sequence alignment program BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997). There are many variants and specific implementations of this basic idea (see Table 31.1) with most differences occurring in the following areas:

Figure 31.3. An example of a multiple alignment: the (small part of the) family of alanine racemase.

Multiple Alignment Construction Simultaneous alignment of several sequences is a NP-hard computational problem (Just, 2001), so most algorithms use heuristic approaches, ranging from hierarchical build-up procedures (PSI-BLAST, PileUp) through constructing an approximate phylogenetic tree and using it as a guide in alignment calculation (CLUS-TALW (Higgins and Gibson, 1995; Jeanmougin et al., 1998)) to stochastic minimization techniques, such as simulated annealing (Godzik and Skolnick, 1994) or hidden Markov models (Karplus et al., 1997).

How to Analyze the Multiple Alignment? How to extract the most relevant information from the multiple alignment? For instance, there are large groups of closely related proteins that do not add much information. Some algorithms simply average the composition at the aligned positions (GCG-Profile) or try to maximize the information content at each position (PSI-BLAST) while others calculate sequence weights from the matrix of interfamily similarities (FFAS).

How is the Similarity Between a Representation of a Family and a Sequence (or a Second Family) Calculated? Some methods compare a representation of a family (profile, position-specific mutation matrix, and hidden Markov model) to a sequence (GCG-Profile or PSI-BLAST), while others compare two families (BLOCKS, FFAS). Also specifics of the scoring methods vary between methods.

Table 31.2 below summarizes differences between several leading profile alignment algorithms. It is interesting to note that despite very different mathematical formulation (profile methods, position-specific mutation matrix methods, or hidden Markov model-based methods), methods are essentially equivalent and use very similar concepts despite very different mathematical notation.

PROTEINS AS SEEN BY A PHYSICIST

All the fold recognition methods discussed so far are based on homology recognition, that is, they assume that structural similarity results from the distant relation between the two proteins. Thus, the hypothesis being tested was whether or not a new protein sequence belongs to a given family of proteins with a specific set of mutation rules. The structure was not used directly and entered the picture only by restricting accepted mutations in different ways at different positions. At the same time, most proteins fold on their own (sometimes with the help of chaperones acting as catalysts of folding), without checking what the structure of their homologues is in databases but following physical laws governing their behavior.

TABLE 31.1. A Short Overview of Major Sequence-Only Fold Recognition/Distant Homology Recognition Algorithms

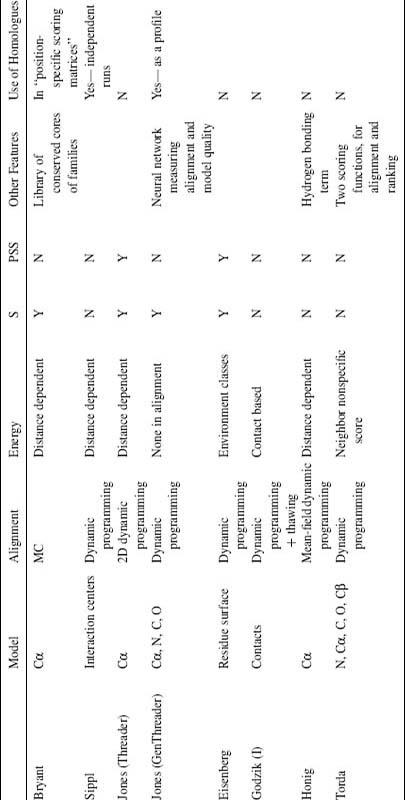

TABLE 31.2. A Short Overview of Several Threading Algorithms

acolumns S and PSS denote use of sequence and predicted secondary structure, respectively.

According to the widely accepted “thermodynamic hypothesis,” the native conformation of a protein corresponds to a global free energy minimum of the protein/solvent system (Anfinsen, 1973; Privalov and Gill, 1988). Therefore, having a correct energy function, one could use the tools of computational physics to search for the native structure in conformational space. Despite many important advances (Bonneau et al., 2001), this approach is still unable to reliably predict a previously unknown structure of a protein for which only a sequence is known. Two principal problems facing the ab initio prediction of protein structure are the lack of adequate molecular potentials and the enormous size of the conformational space of even the smallest protein. Comparing the energy of the same system in two (or more) conformations, as done in fold recognition methods, avoids the latter problem, but unfortunately, as will be discussed later, introduces many new complications.

Energy-based fold recognition methods can be compared to minimization by a grid search, where the grid points where the energy is being calculated are based on known protein structures. Because of the visual analogy of energy calculations using a sequence of one protein forced (threaded through) to adopt a structure of another, energy-based fold recognition was called threading (Godzik and Skolnick, 1992; Bryant and Lawrence, 1993). Since large structural databases must be scanned, energy calculations in threading algorithms by necessity must be optimized for speed. Many different threading algorithms have been developed (Finkelstein and Reva, 1990; Bowie, Luethy, and Eisenberg, 1991; Godzik, Skolnick, and Kolinski, 1992; Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1992; Maiorov and Crip-pen, 1992; Sippl and Weitckus, 1992; Bryant and Lawrence, 1993; Ouzounis et al., 1993; Matsuo and Nishikawa, 1994; Yi and Lander, 1994; Selbig, 1995; Thiele, Zimmer, and Lengauer, 1995; Wilmanns and Eisenberg, 1995; Alexandrov, Nussinov, and Zimmer, 1996; Koretke, Luthey-Shulten, and Wolynes, 1996; Lathrop and Smith, 1996; Russell, Copley, and Barton, 1996; Tropsha et al., 1996; Jaroszewski et al., 1998b). In all cases, threading algorithms followed the paradigm of sequence alignment with its basic steps of identifying the possible template and building the alignment. As a result, the threading approach to structure prediction has limitations similar to sequence-based fold recognition. First and foremost, an example of the correct structure must exist in the structural database that is being screened. If not, the method will fail. Then, the quality of the model is limited by the extent of actual structural similarity between the template and the probe structure.

Force Fields for Simulations and Threading

To speed up energy calculations, the full three-dimensional structure of a protein is usually simplified. Each level of simplification affects the way the energy of the system is calculated. There are less possible interaction centers and more degrees of freedom are averaged. The interaction energy between generalized centers becomes a potential of mean force (Hill, 1960). By averaging over fast changing degrees of freedom, such as bond vibrations and positions of solvent molecules, potentials of mean force are more adequate to describe long-time processes such as folding, despite some loss of accuracy because of the loss of many details. For instance, it can be shown that potentials of mean force can easily distinguish grossly misfolded proteins from their correctly folded counterparts, something that atom-atom molecular potentials are unable to do (Novotny, Brucolleri, and Karplus, 1984).

In principle, it is possible to derive potentials of mean force from simulation by explicitly averaging fast degrees of freedom. This is done routinely in simulations for simple molecular liquids where accurate potentials of mean force can be obtained by averaging vibrational degrees of freedom. However, for complicated systems such as proteins, this is not possible and parameters are usually obtained from the analysis of regularities in experimentally determined protein structures. There have been many derivations of empirical interaction parameter sets, starting from 1976 (Tanaka and Scheraga, 1976) and continuing until today. Several detailed reviews were published recently (Godzik, Kolinski, and Skolnick, 1995; Rooman and Wodak, 1995; Tobi et al., 2000) and a compilation of existing parameter sets is available through the authors Webpage at bioinformatics.burnham.org. There are still many unanswered questions lingering over the theoretical foundations of derivations of knowledge-based interaction parameters and we can expect significant progress in this area.

Despite the lack of complete success as measured by the ability to predict protein structures from their amino acid sequence alone, existing energy parameters adequately capture many features of interactions within proteins. Potentials of mean force derived from the statistical analysis of interaction regularities in proteins can reliably recognize grossly misfolded structures or wrong crystallographic models (Luethy, Bowie, and Eisenberg, 1992), and access the quality of models prepared in homology modeling (Jaroszewski et al., 1998a). And of course, the same potentials can be used in fold recognition.

Threading Approximations

Using energy to recognize similarity between distant homologues leads to several unique challenges. One of the most important ones is that the energy stabilizing a protein structure comes from interactions between side chains distant in sequence. Scoring of alignments in a sequence-based comparison is based on Eq. 31.1 or its variants, where all contributions to the total score come from comparing residues (or PSMMs or single steps in HMM) at single positions and do not depend on gaps or deletions introduced elsewhere in the alignment. In other words, the score is local and this allows the fast and powerful dynamic programming algorithm to be used for alignments. Energy-based scores are not local and alignment with nonlocal functions is an NP-complete problem, that is, it has the same level of computational complexity as the traveling salesman problem and other famous minimization problems (Lathrop, 1994). From the early days of threading, this forced the use of many approximations.

The most obvious approach is to use alignment technique that could work with nonlocal scoring functions. This was a solution used by a few groups (Bryant and Lawrence, 1993) because of the enormous computational cost and slow convergence. Even then it was necessary to limit the space of possible alignments by eliminating deletions and insertions inside secondary structure elements and restricting lengths. By making these approximations a little stronger, it was possible to use combinatorial brand-and-bound minimization algorithms to find a global alignment minimum (Lathrop and Smith, 1996).

Another solution was to use two-level dynamic programming to optimize interaction partners for each possible pairs of aligned residues (Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1992). By explicitly considering only the most important interactions between strongly interacting residues, the computational overhead was manageable and the Threader algorithm that used this approach was one of the most successful early threading algorithms.

Most other groups used approximations to energy calculations that allowed them to use it in dynamic programming. The most common approximation was a “frozen approximation” (Godzik, Skolnick, and Kolinski, 1992) where interaction partners for energy calculations were “frozen” to be the same as in the template and were updated only after the alignment was made. Several other groups adopted this approach, which could be iterated (interaction partners updated after alignment is calculated to calculate the alignment and so on (Godzik, Skolnick, and Kolinski, 1992; Wilmanns and Eisenberg, 1995) or relaxed for some interactions (Thiele, Zimmer, and Lengauer, 1995)). This allowed fast alignment calculations but for a price of introducing yet another simplification to the energy calculations. A detailed analysis of various approximations and errors made in a specific threading algorithm is discussed in the following section.

Differences between various threading algorithms are usually found in three areas:

Protein Model and Interaction Description: To speed up energy calculations, the full three-dimensional structure of a protein is usually simplified, which profoundly affects the way the energy of the system is calculated. Side chains are described by interaction points, which could be located at Cα or Cβ. positions, special interaction points, or can encompass the entire side chain. The interaction energy can be distant dependent or not, and only some parts of the protein molecule can be included in the energy calculations.

Energy Parameterization: There are many variants of the empirical energy parameter derivation that mostly differ in the assumptions about the reference state (Godzik, 1996).

Alignment Algorithms: Threading energy is a nonlocal function of the alignment between the prediction target sequence and the template structure. Dynamic programming with frozen approximation (Godzik, Skolnick, and Kolinski, 1992), 2D dynamic programming (Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1992), Monte Carlo minimization (Bryant and Lawrence, 1993), branch-and-bound algorithm (Lathrop and Smith, 1996), and various hybrid approaches can be used for the alignment.

Table 31.2 brings together a short summary and comparison of various threading algorithms, with emphasis on “pure threading” algorithms. However, in practice many of these algorithms still rely heavily on sequence information mixing elements of classical threading and homology recognition algorithms. This is especially true for most of the recently developed algorithms or most recent updates of old algorithms, such as 3D PSSM (Kelley, MacCallum, and Sternberg, 2000), GenThreader (Jones, 1998), Bioinbgu (Fischer, 2000), and others. Also many other technical choices influence relative performance of different algorithms, that are compared as “package deals” and it is difficult to establish relative importance of various specific choices. Therefore, despite significant success of many of these algorithms in fold prediction competitions (CASP meetings) and in providing structural insights in many specific biological problems, they have not contributed significantly to our understanding of folding and forces that influence protein structures.

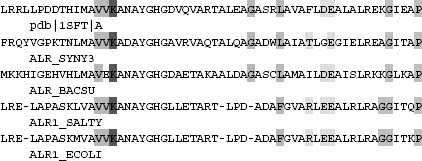

Figure 31.4. An example of a structural alignment between two proteins. Some specific interactions, discussed in the text, are identified in each structure.

What are the Major Sources of Errors in Threading (Zhang et al., 1997)?

In an attempt to study the limits of the topology fingerprint threading, we studied in detail the effects of various approximations on the threading results for the small benchmark of 68 pairs. Structural alignments of all pairs were prepared using the CE algorithm (Shindyalov and Bourne, 1998)—an example of a structural alignment is given in Figure 31.4, with some interactions identified by lines above and below the sequence.

The correct energy of the target protein within its own structure is the reference point used to compare all other values. Figure 31.4 is used to illustrate the discussion with the target protein residues identified by bold:

(1) The correct self-threading energy, but calculated only for structure fragments that do have corresponding fragments in the template protein with their entire interaction environment. Only interactions that are entirely within nonaligned fragments will be omitted.

(2) The same as (1), but only interactions with structure fragments that were aligned to the template protein were used. Therefore, the interaction IA from Figure 31.4 is now omitted. To contrast it with the following approximations, we call it the “correct partners-correct interactions” (CC) approximation.

(3) Interactions from the target protein and the interaction partners from the template protein according to the structural alignment are used to calculate the energy. Therefore, pair interactions contributing to the energy would be (FL + VL, TL + DT, and IE + FR). This is the “wrong partners-correct interactions” (WC) approximation.

(4) Interactions from the template protein and the interaction partners from the target protein according to the structural alignment are used to calculate the energy. In this calculation, interactions contributing to the energy would be (FV, VD, and IF). This is the “correct partners-wrong interactions” (CW) approximation.

(5)Finally, both interactions and interaction partners from the template protein were used, that is, interactions (FL + VL, VL + DF, and IE + FR).). This is the “wrong partners-wrong interactions” (WW) approximation.

The correct energy as well as approximations 1–3 could only be calculated if the experimental structure of the target is known. Approximations 4 and 5 require the correct structural alignment, so indirectly they also rely on knowing the target structure. Therefore, all these energies are unknown for genuine predictions and again can only be estimated using models of the target structure obtained by comparative modeling. In practice, both the comparative modeling and the alignment procedure based only on the target sequence are likely to introduce errors of their own.

Approximations 1 and 2 are introduced to analyze the extend of target-template structural similarity. Approximation 3 is not particularly interesting (once we know the correct structure, what is the point in using wrong partners). All three approximations are included here only for the sake of completeness, and would not be used much in the subsequent analysis.

At first the energy of one of the proteins in the pair was calculated using its own structure and, in several steps, interaction information as supplemented by information derived from the structure of the other protein with the same fold. The last step was equivalent to the energy as calculated in threading. The goal of this experiment was to identify the source of errors made in threading energy calculations. The important point is that approximations 1–4 can be calculated only in the context of a benchmark. Specific residue names are used in examples that follow to identify and differentiate different approximations:

All interactions and amino acid partners from the target protein sequence and structure (FV, TD, IA, and IF) were used. This is the correct self-threading energy.

Interactions and interaction partners from the prediction target protein were used. However, now only interactions with structural fragments aligned to the template protein are allowed. Therefore, the interaction IA from Figure 31.2 is now omitted. This is the “correct amino acid partners-correct interactions” approximation.

Interactions from the target protein are used, but the amino acid partners are taken from the template protein according to the structural alignment. Therefore, interactions contributing to the energy would be (FL + VL, TL + DT, and IE + FR). This is the “wrong amino acid partners-correct interactions” approximation.

Interactions present in the target protein are used, but the amino acid partners from the probe protein were used according to the structural alignment. In this calculation, interactions contributing to the energy would be (FV, VD, and IF). This is the “correct amino acid partners-wrong interactions” approximation. Note that the wrong’’ interaction II from the template is used.

Finally, interactions and interaction partners from the target protein were used, that is, interactions (FL + VL, VL + DF, and IE + FR). Note that the “wrong” interaction II from the template is used. This is the “wrong amino acid partners-wrong interactions” approximation.

Approximation 5 is equivalent to the “frozen approximation” introduced to eliminate the nonlocal character of the scoring function in threading (Godzik, Skolnick, and Kolinski, 1992). “Thawing” the interactions (updating the interaction environment) can bring the energy calculation resulting from 5 into 4, but only if the alignment is correct. Approximation 2 could be used if the correct alignment was known and the structure correctly repacked to allow for changes in the interaction patterns along with changes in sequence. Finally, the self-threading energy 1 corresponds to the stability test of a complete, correct structure of the probe sequence. Our current generation of the topology fingerprint threading algorithm calculates the energy according to approximation 5. It is possible to iteratively converge to 4.

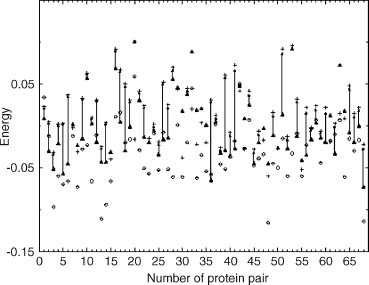

Figure 31.5. Differences between various approximations for energy calculations. Open circles correspond to the real energy, triangles to approximation 4, and crosses to approximation 5 (see text for details).

The results for the 68 pairs are presented in Figure 31.5. Of crucial importance is the observation that the use of the correct partners-wrong interactions (approximation 4), gives a very good approximation of the correct energy. It differs, on the average, by only 1.2 energy units per alignment fragment and 0.25 energy units per residue. Clearly, the interaction patterns in the conserved structural fragments are close enough to be used for energy calculations. Finally, the approximation used as a first step in the topology fingerprint threading algorithm (approximation 5) is clearly the worst, resulting in errors that are about 6 energy units per aligned fragment on average. In other words, the frozen approximation introduced for computational speed in the context of the current interaction definition is terrible. Basically, the pair contribution to the interaction energy using the frozen approximation is wrong, and the error is of the same magnitude as the pair interaction itself.

These results suggest at least two possible ways of improving the sensitivity of threading. One is to move beyond the “frozen approximation” to at least the “correct partners-wrong interactions” approximation. Unfortunately, the scoring function becomes nonlocal, prohibiting the use of dynamic programming alignment (Lathrop, 1994). Another possibility is to change the interaction definition so that the energy differences resulting from approximations 2-5 are smaller. The set of aligned proteins can be used to select the protein representation and associated interaction scheme that minimizes this difference.

Comparing and Assessing Various Fold Recognition Algorithms

The ultimate test of fold recognition methods is the prediction of the folds of new proteins, when only their sequences are known and before any structural information is available. Dedicated meetings, such as the Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) meeting in Asilomar, California bring together almost all groups actively developing fold recognition algorithms. In these meetings, structure prediction groups are provided with sequences of proteins and the structures that are about to be solved but are not yet publicly available. Therefore, all structure predictions are done blind, without any knowledge of the actual structure. This provides a perfect opportunity to compare the performance of various structure prediction algorithms. The last CASP meeting took place in December 2000. The most interesting result from the last CASP meetings is that methods based only on the sequence information, such as HMM methods (Karplus et al., 1997) or profile-profile alignment methods (Rychlewski et al., 2000) compete with energy only threading methods (Sippl and Weitckus, 1992; Bryant and Lawrence, 1993) as well as with hybrid methods combining contributions both from sequence and structure (Jones et al., 1999; Koretke et al., 1999). In regular CASP meeting, the predictions are submitted by research groups that are free to combine results from fold prediction algorithms with other approaches, their own intuition, biochemical knowledge, and so on. To focus on direct comparison of algorithms, an automated comparison of fold prediction servers (CAFASP experiment) was initiated at CASP3 (Fischer et al., 2001). To avoid comparison based on small number of examples, an ongoing test and comparison of fold prediction algorithms LiveBench (Bujnicki et al., 2001) was initiated and is now in its fourth year.

However, for development of new methods, another choice is to use benchmarks or sets of proteins, whose structure is predicted and is known. We call them prediction targets. For each target, its sequence is matched against a large number of proteins with known structures (templates). The goal is to identify the most appropriate template protein. In a benchmark, the quality of a given prediction method can be measured by the number of targets for which the template chosen by the algorithm was indeed similar to its real structure. One of the early benchmarks was based on 68 proteins identified by Fischer et al. (1995) and was used to evaluate several variants of 3D profile methods developed at UCLA (1996), the RFSRV method (Fischer, 2000) and the GeneFold algorithm (Jaroszewski et al., 1998a). Progress in automated structure comparison and easy availability of fold classification databases make it possible to develop larger benchmarks—most popular benchmarks are based on existing classifications of protein structures, such as SCOP.

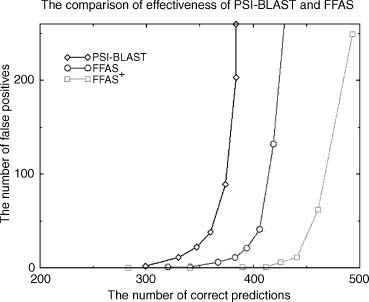

Figure 31.6. Sensitivity plot for several sequence only fold recognition algorithms on a benchmark of 929 proteins identified by SCOP and DALI as being structurally similar. Number of correct predictions for every method is shown as a function false predictions with the same level of significance. PDB-BLAST is a specific strategy of using PSI-BLAST for fold recognition, FFAS is a profile-profile alignment described previously (Rychlewski et al., 2000).

An example of such comprehensive benchmark of over 900 proteins pairs was built using structure clustering from DALI (1995) and SCOP (1995) databases. The DALI database was used for selection of protein pairs of significant structural similarity but low sequence similarity and SCOP was used to verify the structural similarity of the pair and to assess the level of similarity (fold, superfamily, and family). The full benchmark list (as well as a full list of results for all methods discussed here) is available from our Web server at bioinformatics.burnham-inst.org/benchmarks the FFAS page (Figure 31.6).

SUMMARY

We are still missing a basic understanding of sequence/structure/function relationships in proteins. Analogy-based prediction algorithms remain the only reliable fold prediction tools. New methods, such as threading and hybrid threading/sequence fold recognition, can often recognize even the most distant homologues and, in some cases, even unrelated proteins with similar overall structures. This pushed the envelope of analogy-based function analysis to the point that the majority of newly sequenced genomes can be tentatively assigned to already characterized protein superfamilies. However, at this evolutionary distance, fold prediction is no longer equivalent to function prediction. Instead of having the same exact function, distantly related proteins might share some functional analogy that is not obvious to the casual observer. The main challenge facing fold recognition field is to develop tools to follow the structure prediction with function prediction and analysis.