32

DENOVO PROTEIN STRUCTURE PREDICTION: METHODS AND APPLICATION

INTRODUCTION

The goal of de novo structure prediction is to predict the native structure of a protein given only its amino acid sequence. It is generally assumed that a protein sequence folds to a well-defined ensemble average commonly referred to as the native conformation or native ensemble of conformations. It is also commonly assumed that the native state is at or near the global free energy minimum and that this minimum is accessible, leading to folding rates spanning not longer than minutes (albeit spanning >6 orders of magnitude). Exciting exceptions to these assumptions exist, but these assumptions remain quite safe for a large majority of proteins. The problem of finding this native state can be broken into two smaller problems: first, developing an accurate potential and, second, developing an efficient method for searching the energy landscape arising from the potential.

Many methods that are today referred to as de novo have previously and/or alternately been referred to “new folds” or ab initio methods. For the purpose of this review, we will classify a method as de novo structure prediction if that method does not rely on homology between the query sequence and a sequence in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to create a template for structure prediction. De novo methods, by this definition, are forced to consider much larger conformational landscapes than fold recognition and comparative modeling techniques that limit the conformational space by exploring regions near an initial structural template. Sampling this large conformational space is computationally intense and has inhibited de novo structure prediction from being useful in certain applications. Recent advances are just now, for example, proving de novo structure prediction useful in full genome annotation.

To date the most successful methods for structure prediction have been homology-based comparative modeling and fold recognition (Moult et al., 1999). These methods rely on homologous or weakly homologous sequences of known structure that are frequently not available. When homologous sequences are not available, successful methods for local structure have included predicting secondary structure and local structure patterns (Rost and Sander, 1993; King et al., 1997; Bystroff and Baker, 1998; Jones, 1999; Karplus et al., 1999). Local prediction methods are valuable but are limited and cannot accurately model a whole protein. Our review will focus on current methods for predicting tertiary structure in the absence of homology to a known structure and will discuss these local prediction methods only in the context of tertiary structure prediction.

Many of the methods used today to predict protein structure use information from the PDB. Information extracted from the PDB can be found in the parameters of knowledge-based scoring functions, the training sets of machine learning approaches, and the coordinate libraries of methods that use fragments or templates from the PDB. To test the performance of any one of these approaches, one must carefully remove sequences that are homologous to proteins in the test set from all databases used by the method in question. Any errors or oversights made at this stage could lead to overestimates of success. These concerns are addressed by the critical assessment of structure prediction (CASP) and will be discussed later on.

In spite of recent progress, many issues must still be resolved if a consistently reliable de novo prediction scheme is to be developed. There is still no one method that performs consistently across all classes of proteins (most methods perform worse on all-beta proteins), and all methods examined seem to fail totally on sequences longer than 150 residues in length (although in some rare cases larger alpha and alpha-beta proteins have been successfully predicted by de novo methods, the methods are in no way reliable at these lengths).

A common pedagogical distinction between prediction methods has been the distinction between methods based on statistical principles on the one hand and physical or first principles on the other hand. Most current successful de novo structure prediction methods fall into the statistics camp. We will not discuss this distinction here at great length except for noting that one of the shortcomings of this artificial division is that most effective structure prediction methodologies are in fact a combination of these two camps. For example, several methods that are described as based on physical or first principles employ energy functions and parameters that are statistical approximations of data (e.g., the Lennard-Jones representation of van der Waals forces is often thought of as a physical potential but is a heuristic fit to data). A more useful distinction may be the distinction between reduced complexity models (RCMs) and models that use atomic detail. In this review, we will discuss low-resolution (models containing drastic reductions in complexity such as unified atoms and centroid representations of side-chain atoms) and high-resolution methods (methods that represent protein and sometimes solvent in full atomic detail) focusing on this practical classification/division of methods in favor of distinctions based on a given method’s derivation or parameterization.

Some of the topics covered in this review will be discussed in the context of applications of de novo structure prediction, specifically the applications of genome annotation and function prediction. Also, many examples in the text will center on the de novo structure prediction method Rosetta; a section describing the Rosetta method is thus presented. Domain prediction is a critical preprocessing step that expands the reach of de novo methods to larger proteins. This step, domain prediction, is necessary for annotating full genomes allowing de novo methods increased coverage; although these methods are generally sequenced based, they are discussed briefly due to this high relevance. As important as increasing the coverage of structure prediction methods is reducing the complexity of folding models, which lessens the computational time needed to obtain a low-resolution structure while still allowing the process to compute some functional information. The scoring functions of common methods are introduced followed by a discussion of high-resolution structure prediction methods. Using high-resolution methods is difficult with genome annotation because of the computational complexity, but it adds tremendous power to function prediction due to its modeling of atomic detail. Next, the topic of postprocessing de novo structures into clusters is covered. Finally, some history and milestones of CASP are discussed and then a more in depth look into applications of de novo structure predictions.

Domain Prediction is a Critical Prerequisite to Structure Prediction

De novo methods have run times that increase dramatically with sequence length. As the size of a protein increases, so does the size of the conformational space associated with that protein. Current de novo methods are limited to proteins and protein domains less than 150 amino acids in length (with Rosetta the limit is ~150 residues for alpha/beta proteins, 80 for beta folds, and ~150 residues for alpha only folds). This limit means that roughly half of the protein domains seen so far in the PDB are within the size limit of de novo structure prediction. Two approaches to circumventing this size limitation are (1) increasing the size range of de novo structure prediction and (2) dividing proteins into domains prior to attempting to predict structure. A domain is generally defined as a portion of a protein that folds independently of the rest of the protein. Dividing query sequences into their smallest component domains prior to folding is one straightforward way to dramatically increase the reach of de novo structure prediction. For many proteins, domain divisions can be easily found (as would be the case for a protein where one domain was unknown and one domain was a member of a well-known protein family), while several domains remain beyond our ability to correctly detect them. The determination of domain family membership and domain boundaries for multidomain proteins is a vital first step in annotating proteins on the basis of primary sequence and has ramifications for several aspects of protein sequence annotation; multiple works describe methods for detecting such boundaries. In short, most protein domain parsing methods rely on hierarchically searching for domains in a query sequence with a collection of primary sequence methods, domain library searches, and matches to structural domains in the PDB (Chivian et al., 2003; Kim, Chivian, and Baker, 2004; Liu and Rost, 2004).

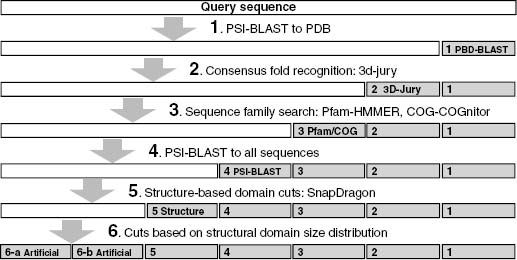

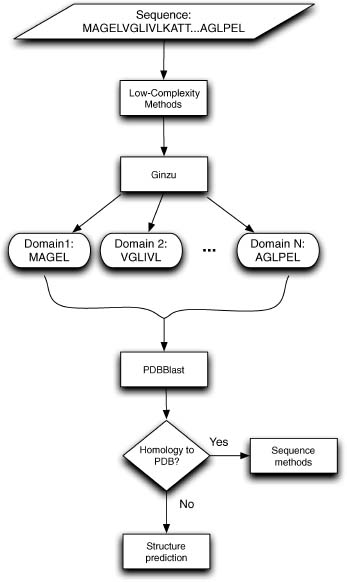

Recent works use coarse-grained structural simulations and predictions coupled with methods for assigning structural domain boundaries to three-dimensional structures to detect protein domains from sequence. The guiding principle behind this approach is that very low-resolution predictions will pick up overall patterns of the polypeptide packing into distinct structural domains. An interesting recent work attempted to use local sequence signals to detect structure domain boundaries under the assumption that there would be detectable differences in local sequence propensities at domain boundaries (Galzitskaya and Melnik, 2003). As of yet these methods have unacceptably high error rates and are far too computationally demanding for use in genome-wide predictions (David Kim, personal communication) (George and Heringa, 2002). In spite of the limitations mentioned above, these methods (that depend on detecting sequence homologues for a given query sequence) are attractive for proteins that have no detectable homologues or matches to protein domain families, and future work on this front could increase the number of proteins within reach of de novo methods considerably. It is likely that a method that successfully combines these coarse structure-based methods with existing sequence-based methods into a hierarchically organized domain detection program (e.g., Ginzu) will eventually outperform any existing method at domain parsing and greatly increase the accuracy of downstream structure prediction. Figure 32.1 shows a schematic domain detection program (this schematic is implemented as the program Ginzu that is developed in conjunction with Robetta, a publicly available server that does domain prediction, homology modeling, and de novo modeling: http://robetta.org (Bradley et al., 2005)).

Figure 32.1. Schematic outline of the Ginzu program for domain parsing. Methods with higher reliability are used at the top of the hierarchy, with sequence matches to the PDB being the highest quality information. As higher reliability methods are exhausted, noisier methods are used (such as parsing multiple sequence alignments, step 4, and guessing domain boundaries based on the distribution of domain sizes in the PDB). Sequence regions hit by higher confidence methods (represented as gray rectangles) are masked and the remaining sequence (represented by white rectangles) are forwarded onto the remaining methods. Steps 1-4 and 6 are currently implemented in the Ginzu program, and step 5 (adding sequence homologue independent methods such as structure-based domain parsing from sequence to the procedure) represents possible future work.

REDUCED COMPLEXITY MODELS

To overcome the sampling problems mentioned in the introduction, most methods for fold prediction to date have involved some significant reduction in the detail that is used to model the polypeptide chain. Methods for reducing protein structure to discrete low-complexity models can be divided into two major classes: lattice and off-lattice models.

Lattice models entail confining possible special coordinates to a predefined three-dimensional grid, and off-lattice models reduce degrees of freedom along the backbone to a set of discrete angles. For a more exhaustive description of these methods than we provide below and their reduced-complexity movesets, we refer the reader to earlier reviews of de novo structure prediction methods (Bonneau and Baker, 2001).

Lattice Models

Lattice models have a long history in modeling the behavior of polymers due to their analytical and computational simplicity (Dill et al., 1995). The evaluation of energies on a lattice can be achieved quite efficiently (integer math can be made quite fast) and methods involving exhaustive searches of the available conformational space become feasible (Skolnick and Kolinski, 1991; Hinds and Levitt, 1994; Ishikawa, Yue, and Dill, 1999). However, lattice methods have a somewhat restricted ability to represent subtle geometric considerations (strand twist, secondary structure propensities, and packings) and can reproduce the backbone with accuracies no greater than approximately half the lattice spacing (Reva et al., 1996). The most common systematic error observed for a variety of lattice models is their inability to reproduce helices, and most lattice models exhibit various degrees of secondary structure bias (Park and Levitt, 1995). Given the importance of regular secondary structure in proteins, this is clearly a problem. Recent successful tests, however, have shown that the computational advantages of lattice models may outweigh the problems associated with their systematic biases (Hinds and Levitt, 1994; Kolinski and Skolnick, 1994a; Kolinski and Skolnick, 1994b; Samudrala et al., 1999a).

Discrete State Off-Lattice Models

Most off-lattice reduced complexity models fix all side-chain degrees of freedom and all bond lengths. The most common practice is to limit the side chain to a single rotamer or further to the Cb or to one or more centroids plus backbone atoms (Sternberg, Cohen, and Taylor, 1982; Simons et al., 1997). Discrete state models of the protein backbone usually fix all side-chain degrees of freedom and limit the backbone to specific phi/psi pairs: models containing from 4 to 32 phi/psi states representing various strand, helix, and loop conformations have been described in the literature (Park and Levitt, 1995). It has been shown that properly optimized six state models (i.e., models that account for local features observed in proteins like strands, helices, and canonical loops) can reproduce native contacts, preserve secondary structure, and fit the overall coordinates of the native state as well as the 18-state lattice models that do not account for such protein-specific information (Park and Levitt, 1995).

Narrowing the Search with Discrete State Local Structure Prediction

Local sequences excised from protein structures often have stable structures in the absence of their global contacts, demonstrating that local sequences can have a strong, sequence-dependent structural bias toward one or more well-defined structures (Marqusee, Robbins, and Baldwin, 1989; Blanco, Rivas, and Serrano, 1994; Munoz and Serrano, 1996; Yi et al., 1998; Callihan and Logan, 1999). Several examples also exist of excised fragments having little observable structure, indicating that the strength and the multiplicity of these local biases are highly sequence dependant. Still other studies have focused on sequences that are observed to fold to different conformations depending on their global sequence context, again demonstrating the possible multiplicity of local structure biases (Kabsch and Sander, 1984; Cohen, Presnell, and Cohen, 1993).

Despite the unavoidable ambiguities in local sequence-structure relationships, secondary structure prediction methods have been steadily improving (Orengo et al., 1999a). The prediction methods that accurately predict the type, strength, and possible multiplicity of these local structure biases for any given query sequence segment drastically reduce the size of the available conformational landscape.

Bystroff et al. developed a method that recognizes sequence motifs (ISITES) with strong tendencies to adopt a single local conformation that was used to make good local structure predictions in CASP2 (Bystroff et al., 1996; Han, Bystroff, and Baker, 1997; Bystroff and Baker, 1998; Bystroff, Thorsson, and Baker, 2000; Bystroff and Shao, 2002). I-sites is an HMM (hidden Markov Model) method designed to detect strong relationships between sequence and structure as defined by a library of local structure-sequence relationships. One potential advantage of this method is that the I-sites method is not constrained to fragments of a fixed length (Rosetta is constrained to 3- and 9-length fragments) (Bystroff, Thorsson, and Baker, 2000). Thus, larger patterns of local structure bias will be detected more often by this method. Karplus et al. (2003) also used a similar approach to detecting fragments of local structure (a two-stage HMM) as part of their de novo method. These methods have the primary advantage of better performance when local sequence-structure bias is high (e.g., when local structure is strongly and/or uniquely determined by sequence). The TASSER method smoothly combines fragments of aligned protein structure (from threading runs) with regions of unaligned proteins (represented on a lattice for computational efficiency) to effectively scale between the fold recognition and de novo regime (Zhang and Skolnick, 2004).

The above-mentioned experiments and observations suggest that any method attempting to use local sequence-structure biases to guide complexity reductions will have to be adaptive to the strength and the multiplicity of different local sequence-structure patterns. The majority of methods proving successful at CASP3 through CASP6 used secondary structure predictions in one way or another, most often three-state secondary structure predictions were used. In one case, predicted secondary structure elements were fit to the results of initial lattice-based exhaustive enumeration, thus erasing any possible secondary structure bias in initial lattice model prior to all-atom refinement (Samudrala et al., 1999b). The Rosetta method uses secondary structure to bias the selection of fragments of known structure from the PDB. Yet another paradigm is to, given a secondary structure string, reduce the problem of predicting the tertiary fold to the problem of how to assemble rigid secondary structure elements (Eyrich, Standley, and Friesner, 1999). Methods have also been described of determining local structure biases independent of secondary structure prediction algorithms (Srinivasan and Rose, 1995).

Using either fragment substitution (assembling fragments of local structure) as a moveset or local structure constraints derived from predicted local structure also has the advantage that the subsequent global search is limited to protein-like regions of the conformational landscape (helices, correct chirality of secondary strand packing, strands and sheets with correct twist, etc).

There are two main ways to use local structure prediction as an overriding/hard constraint on the global search: (1) using fragments to build up global structures (local structure defining the moveset) and (2) using local structure as a hard constraint (local structure heavily modifying the objective function).

There is likely to be an upper limit on the accuracy of secondary structure prediction methods, due to their failure to account for nonlocal interactions. The best secondary structure prediction algorithms have three-state accuracies of 76-78%, and any de novo method must account for this error rate to make consistently successful predictions (Rost and Sander, 1993; Jones, 1999). A milestone for de novo structure prediction, which takes nonlocal interactions into account, will be the production of models with secondary structure predicted more accurately than possible with traditional secondary structure methods.

SCORING FUNCTIONS FOR REDUCED COMPLEXITY MODELS

Once a model for representing the protein is chosen that sufficiently reduces the complexity of the conformational search, a scoring or energy function that works in the chosen low-complexity space must be developed. The energy function must adequately represent the forces responsible for protein structure: solvation, strand hydrogen bonding, and so on. Given that most low-complexity models do not explicitly represent all atoms and can reproduce even the native state backbone with only limited accuracy, any energy function designed to work in the low-complexity regime must represent these forces in a manner robust to such systematic error (the systematic limitations of the model). Finally, these functions must be computationally efficient, for the initial stages of any conformational search require huge numbers of energy evaluations. Because of the shortcomings of molecular mechanics-based potentials and the considerations above, many methods developed in the past 10 years utilize scoring functions derived from the PDB, which favor arrangements of residues that are commonly found in known protein structures and minimize the contribution of rarely seen arrangements. The effect scoring functions have on our applications of genome annotation and function prediction is not as obvious and direct as others, but efficient and accurate scoring functions nevertheless have a large impact on how scalable our methods are to a genome level.

Solvation-Based Scores

It has been long thought that the hydrophobic effect is the principal driving force behind protein folding (Baldwin, 1999). There are many diverse methods for determining the fitness of backbone conformations based on solvation or hydrophobic packing, and the debate over the proper functional form for representing solvation effects represents an open question of considerable importance and interest (Park, Huang, and Levitt, 1997). A common approach is to classify sites in the protein according to the degree of solvent exposure. This is done by classifying sites either by the exposed surface area or by the number of nearby residues and then determining the frequencies of occurrences of the amino acids in each type of sites (Bowie and Eisenberg, 1994). The score of an amino acid at a site is then taken to be the logarithm of the amino acid’s frequency of occurrence at that type of site (see Table 32.1 for equation). This type of residue environment term favors placement of hydrophobic amino acids at buried positions and hydrophilic amino acids at exposed positions. The final score is a weighted sum of the scores.

Another commonly used class of functional forms for solvation consists of global measures of hydrophobic arrangement. One simple global quantity is a residue’s distance from the entire conformation’s center of mass, which can be used to calculate quantities analogous to the hydrophobic radius of gyration. Bowie and Eisenberg (1994) used this type of function, coined hydrophobic contrast, in combination with other terms, including a surface area-based term, to fold small alpha helical proteins using an evolutionary algorithm.

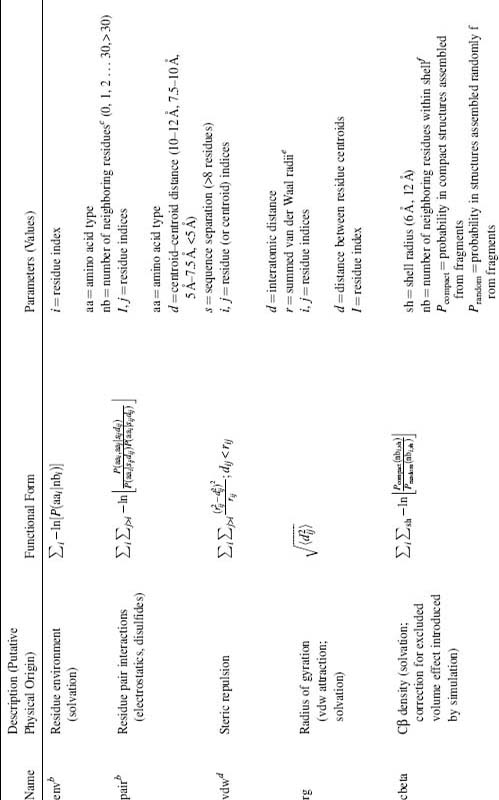

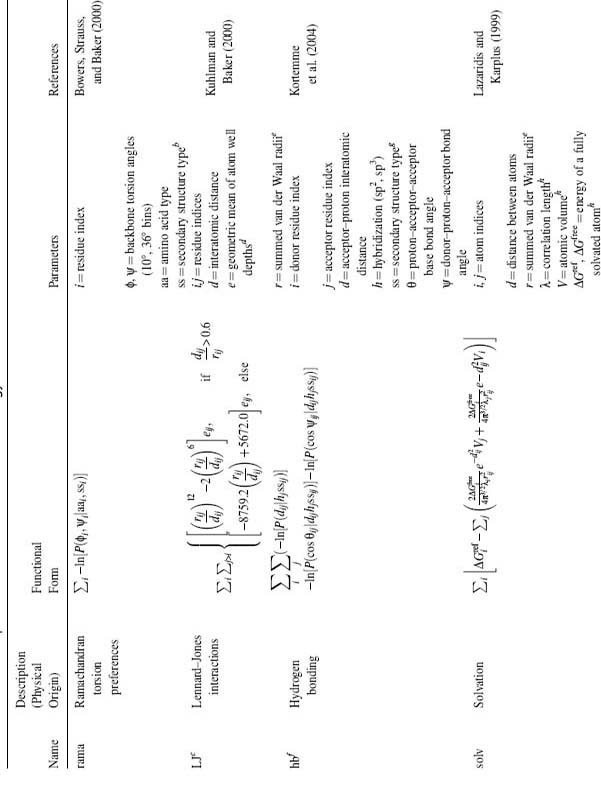

TABLE 32.1. Components of the Rosetta Energy Functiona

a All terms originally described in references Simons et al., 1997, 1999.

b Binned function values are linearly interpolated, yielding analytic derivatives.

c Neighbors within a 10Å radius. Residue position defined by Cβ coordinates (Cα for glycine).

d Not evaluated for atom (centroid) pairs whose interatomic distance depends on the torsion angles of a single residue.

e Radii determined from (1) 25th closest distance seen for atom pair in pdbselect25 structures, (2) the fifth closest distance observed in X-ray structures with better than 1.3Å resolution and <40% sequence identity, or (3) X-ray structures of <2Å resolution, excluding i, i + 1 contacts (centroid radii only).

f Residue position defined by Cβ coordinates (Cα for glycine).

g Interactions between dimers

within the same strand are neglected. Favorable interactions are limited to preserve pair-wise strand

interactions, that is, dimermcan interact favorably with dimers from at most one strand on each side,

with the most favorable dimer interaction (SS ,σ + SShb + SSd)

determining the identity of the interacting strand. SSdσ is exempt from the requirement of

pair-wise strand interactions. SShb is evaluated

only for m, n pairs for which SS

,σ + SShb + SSd)

determining the identity of the interacting strand. SSdσ is exempt from the requirement of

pair-wise strand interactions. SShb is evaluated

only for m, n pairs for which SS ,θ is favorable. SSdσ is evaluated only for m, n pairs for which SS

,θ is favorable. SSdσ is evaluated only for m, n pairs for which SS ,θg and SShb are favorable. A bonus is awarded for each

favorable dimer interaction for which |m_n| > 11 and strand separation is >8 residues.

,θg and SShb are favorable. A bonus is awarded for each

favorable dimer interaction for which |m_n| > 11 and strand separation is >8 residues.

hA sheet is constituted of all strands with dimer pairs <5.5Å apart, allowing each strand having at most one neighboring strand on each side. Discrimination between alternate strand pairings is determined according the most favorable dimer interaction. Probability distributions fitted to c(nstrands) –0.9nsheets – 2.7nlone_strands, where c(nstrands)=(0.07, 0.41, 0.43, 0.60, 0.61, 0.85, 0.86, 1.12).

Huang and Levitt used this type of function to recognize native structures (Huang, Subbiah, and Levitt, 1995; Samudrala et al., 1999b). One problem with the above global functions is that they assume that proteins are ideally spherical in shape when in actuality native proteins exhibit a much larger range of shapes. A more flexible approach uses an ellipsoidal approximation of the shape of the hydrophobic core that does not require a significant increase in computation and was shown to aid in the selection of near-native conformations from decoy sets containing a high number of protein-like yet incorrect compact conformations. The problem associated with these functions is that they will inevitably exclude a small percentage of protein structures that deviate from their assumptions concerning shape and thus fail when a protein is divided into small subdomains or contains large invaginations (1HQI is a toroid). In spite of this potential downfall, they have demonstrated their usefulness in several methods due to their ability to recognize the majority of small hydrophobic cores, their simplicity, and the speed with which they can be computed.

Pair Interactions

Many low-resolution scoring functions utilize an empirically derived pair potential in place of or in addition to the residue environment term described above. The most common of these potentials are functions of the position of a single center per residue (Ca, Cb, or centroid/ united atom center) and are thus quite computationally efficient; all-atom functions have also been used (Samudrala et al., 1999c). Many variations of pair terms have been developed, with the two main branches of methods being distance-dependant and contact-based methods (Sippl, 1995; Miyazawa and Jernigan, 1999). Like the sequence-structure bias mentioned above, these scoring functions are sometimes justified by positing that the arrangements of residues in proteins follow a Boltzman distribution E(x) = kT ln P(x), where x is a feature such as the occurrence of two residues separated by a distance less than r. Alternatively, these scoring functions may be seen purely as probability distribution functions (Domingues et al., 1999; Simons et al., 1999c). In the former case, the optimization may be viewed as a search for the lowest energy configurations and, in the latter, a search for the highest probability configurations. For most applications, there is little practical difference between the two viewpoints. The issue becomes more substantive, however, when such database-derived scoring functions are combined with physics-based potentials, as will likely become increasingly useful.

There are several problems associated with statistically derived pair potentials. The assumption that summing over component interactions can represent free energies is not generally valid across all interactions present in proteins, and thus the basic functional form may not be adequate to represent the free energy of a decoy conformation (Mark and van Gunsteren, 1994; Dill, 1997). The most significant problem with pair potentials is that they are dominated by hydrophobic/polar partitioning that gives rise to anomalous effects, such as a long-range repulsion between hydrophobic residues (Thomas and Dill, 1996). This can be corrected by conditioning the pair distributions on the environments of the two residues, which largely eliminates these undesired effects (Simons et al., 1997). With the elimination of the otherwise overwhelming influence of hydrophobic partitioning, specific interactions such as electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged residues dominate the pair scoring/energy functions, and hydrophobic interactions make relatively modest contributions. The pair term, in this case, is perhaps best viewed as the second term in a series expansion for the residue-residue distributions in the database in which the residue environment distributions are the first term.

Some of the earliest comprehensive tests of the discriminatory power of these pair potentials were done in the context of threading self-recognition (Novotny, Bruccoleri, and Karplus, 1984). Later work demonstrated that the self-recognition problem was not a sufficiently challenging test of scoring functions and focused on the performance of multiple pair-wise energy functions on larger more diverse sets of conformations (Jernigan and Bahar, 1996; Jones and Thornton, 1996; Park and Levitt, 1996; Park, Huang, and Levitt, 1997; Eyrich, Standley, and Friesner, 1999). The performance of the various energy functions at recognizing native-like structures in large ensembles of incorrect “decoys” highly depends on the methods used to create the decoy sets, highlighting the fact that an energy function that works well in the context of one method will not necessarily work well given a decoy set created using an orthogonal method.

Sequence-Independent Terms/Secondary Structure Arrangement

Many features of proteins, such as the association of beta strands into sheets, can be described by sequence-independent scoring functions. Several early approaches to folding all-beta proteins were protocols dominated by initial low-resolution combinatorial searches of possible strand arrangements and were concerned only with the probability of different strand arrangements (Cohen, Sternberg, and Taylor, 1980; Cohen, Sternberg, and Taylor, 1982; Chothia, 1984; Reva and Finkelstein, 1996). These early methods narrow the conformational space by only considering sequence-specific effects in the context of highly probable strand arrangements. Several of the relatively successful methods at CASP3 incorporated secondary structure packing terms (Lomize, Pogozheva, and Mosberg, 1999; Simons et al., 1999b). Ortiz et al. used an explicit hydrogen bond term in combination with a “bab” and a “bba” chirality term to ensure protein-like secondary structure formation. It cannot be expected that a low-complexity lattice model produce the correct chirality or subtle higher order effects like strand twist and these rules sensibly correct for these expected shortcomings (Ortiz et al., 1999). The Rosetta method used three terms that monitored strand-strand pairing, sheet formation, and helix strand interactions to ensure protein-like secondary structure arrangements.

Structures from Limited Constraint Sets

The obvious drawback of current low-resolution de novo structure prediction methods is their relatively low accuracy and reliability. Even limited amounts of experimental data on the structure of a protein can remedy this considerably. For example, Rosetta produced accurate structures in conjunction with NMR chemical shift data (to enhance fragment selection) and sparse NOE constraints (Bowers, Strauss, and Baker, 2000). Distance constraints from cross-linking followed by mass spectrometry could also be readily incorporated into such an approach and potentially could be obtained on a high-throughput scale (see Chapter 7).

ROSETTA DE NOVO STRUCTURE PREDICTION

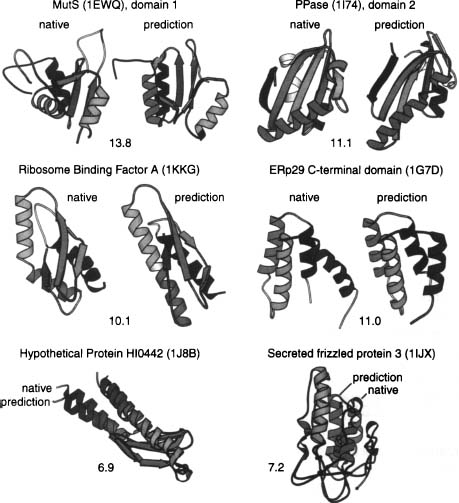

Throughout this work, we have used and will use examples drawn from or centered on the Rosetta de novo structure prediction protocol and will thus provide a brief overview of Rosetta before continuing to discuss key elements of the procedure in greater detail (Simons et al., 1997; Simons et al., 1999a; Simons et al., 1999b; Bonneau, Strauss, Baker, 2001a; Rohl et al., 2004b) (see Figures 32.2 and 32.3). Results from the fourth and fifth critical assessments of structure prediction (CASP4, CASP5, CASP6) have shown that Rosetta is currently one of the best methods for de novo protein structure prediction and distant fold recognition (Bonneau et al., 2001c; Lesk, Lo Conte, and Hubbard, 2001; Bradley et al., 2003; Chivian et al., 2003). Rosetta was initially developed as a computer program for de novo fold prediction but has been expanded to include design, docking, experimental determination of structure from partial data sets, protein-protein interaction, and protein-DNA interaction prediction (Kuhlman and Baker, 2000; Chevalier et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2003a; Gray et al., 2003b; Kuhlman et al., 2003; Kortemme et al., 2004; Rohl et al., 2004a; Rohl, 2005). When we refer to Rosetta in this work, we will be primarily referring to the de novo or ab initio mode of the Rosetta code base. Early progress in high-resolution structure prediction has been achieved via combinations of low-resolution approaches (for initially searching the conformational landscape) and higher resolution potentials (where atomic detail and physically derived energy functions are employed). Thus, Rosetta structure prediction is carried out in two phases: (1) a low-resolution phase where overall topology is searched using a statistical scoring function and fragment assembly and (2) an atomic detail refinement phase using rotamers and small backbone angle moves and a more physically relevant (detailed) scoring function.

Rosetta de novo (Rosetta) uses information from the PDB to estimate the possible conformations for local sequence segments. The procedure first generates libraries of local sequence fragments excised from a nonredundant version of the PDB on the basis of local sequence similarity (3- and 9-residue matches between the query sequence and a given structure in the PDB) (Simons et al., 1997).

Using the PDB for local sequence information was inspired by careful studies of the relationship between local sequence and local structure (Han, Bystroff, and Baker, 1997), which demonstrated that this relationship was highly variable on a sequence-specific basis and that there is a great deal of sequence-specific local structure that could be recognized even in the absence of global homology. The selection of fragments of local structure on the basis of local sequence matches dramatically reduces the size of the accessible conformational landscape. In practice we see that, as desired, for some local sequence segments there is a strong bias toward a single local structure in the computed local structure fragments, while other local sequences exhibit a wide range of local conformations in the fragment library.

Using fragment substitution as a set of allowable moves to optimize Rosetta’s objective function does have drawbacks. As the structure collapses late in the simulation and forms contacts favorable according to the energy function, the acceptance rate of fragment moves becomes unworkably small. This is due to the fact that the substitution of 6 or 18 backbone dihedral angles creates large perturbations to the Cartesian coordinates of parts of the protein distant along the polypeptide chain. The likelihood that such perturbations cause steric clashes and break energetically favorable contacts late in a given simulation is exceedingly large. To recover effective minimization of the Rosetta score after initial collapse, several additional move types have been added to the Rosetta moveset. The simplest move type consists of small-angle moves within populated regions of the Ramachandran map. Additional moves, descriptively named “chuck,” “wobble,” and “gunn,” aim to perform fragment insertions that have small effects far from the insertion limiting the possibility of breaking favorable contacts. These additional move types are also critical to the modeling of loops in homology modeling and are described in detail elsewhere (Rohl et al., 2004).

Figure 32.2. Rosetta structure prediction protocol: Rosetta begins by determining local structure conformations (fragments) for 3- and 9-mer stretches of the input sequence. Then multiple fragment substitution simulated annealing searches are done to find the best arrangement of the fragments according to Rosetta’s low-resolution scoring function (Table 32.1). The resulting structures then undergo a high-resolution refinement step based ona more physically based scoring function (Table 32.2). Finally, the structures are clustered by RMSD (to each other, as the native is unknown) and the centers of the largest clusters are chosen as representative folds (the centers of the largest clusters are likely to be correct fold predictions).

Rosetta fragment generation works well even for sequences that have no homologues in the known sequence databases owing to the PDB structure coverage of possible local sequence at the 3- and 9-residue length. Tertiary structures are generated using a Monte Carlo search of the possible combinations of likely local structures minimizing a scoring function that accounts for nonlocal interactions such as compactness, hydrophobic burial, specific pair interactions (disulfides and electrostatics), and strand pairing.

Figure 32.3. Examples of de novo structure predictions generated using Rosetta. A, B and C are examples from our genome-wide prediction of domains of unknown function in Halobacterium NRC-1 (Bonneau et al., 2004). In each case, the predicted structure is shown next to the closest structure-structure match to the PDB. For A, B, and C, only the backbone ribbons are shown, asthese predictions were not refined using the all-atom potential and are examples of the utility of low-resolution prediction in determining function. Panel D shows a recent prediction where high-resolution refinement subsequent to the low-resolution search produced the lowest energy conformation, a prediction of unprecedented accuracy (provided by Phil Bradley).

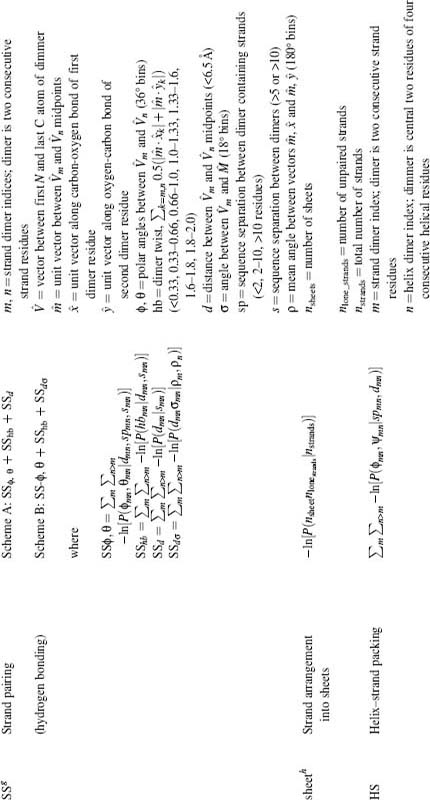

The Rosetta score for this initial low-resolution stage is described in its entirety in Table 32.1. For the second stage, refinement, the centroid representations of amino acid side chains used in the low-resolution phase are replaced with atomic detail rotamer representations. Rotamers are generally defined as the different acceptable conformations of atoms in the amino acid side chains. The scoring function used during this refinement phase includes solvation terms, hydrogen bond terms, and other terms with direct physical interpretation. See Table 32.2 for a full description of the all-atom Rosetta score.

TABLE 32.2. Components of the Rosetta All-Atom Energy Functiona

Also described in Rohl (2005).

a All binned function values are linearly interpolated, yielding analytic derivatives, except as noted.

b Three-state secondary structure type as assigned by DSSP Kabsch and Sander (1983).

c Not evaluated for atom pairs whose interatomic distance depends on the torsion angles of a single residue.

d Well depths taken from CHARMm19 parameter set, Neria et al. (1991).

e Radii determined from fitting atom distances in protein X-ray structures to the 6–12 Lennard Jones potential using CHARMm19 well depths.

fEvaluated only for donor acceptor pairs for which 1.4 ≤ d ≤ 3.0 and 90° ≤ ψ, θ ≤ 180°. Side-chain hydrogen bonds in involving atoms forming main-chain hydrogen bonds are not evaluated. Individual probability distributions are fitted to eighth-order probability distributions and analytically differentiated.

g Secondary structure types for hydrogen bonds are assigned as helical ( j – i = 4, main chain), strand: (|j – i | > 4, main chain) or other.

h Values taken from Lazaridis and Karplus (1999).

i Residue position defined by Cβ coordinates (Cα of glycine).

Using Rosetta-generated structure predictions, we were able to recapitulate many functional insights not evident from sequence-based methods alone (Bonneau et al., 2001b; Bonneau et al., 2002). We have reported success in annotating proteins and protein families without links to known structure with Rosetta (Bateman et al., 2000; Bonneau et al., 2002). Various aspects of this overall protocol will be reviewed in greater detail below. We also encourage the reader to refer to several prior works where the Rosetta method is described in its entirety.

HIGH-RESOLUTION STRUCTURE PREDICTION

We now move to the subject of creating high-resolution protein structures. We have already seen the precursor that reduces the complexity of the protein model and its corresponding scoring functions. High-resolution protein folding builds on these topics but no doubt requires a more accurate all-atom model and a stronger root in physically based scoring functions. With these added requirements, as we shall see, the computational complexity increases.

The most natural starting point for simulating high-resolution protein folding is standard molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (numerically integrating Newton’s equations of motion for the polypeptide chain) using a physically reasonable potential function. There are several problems that have limited the success of such approaches thus far. First, MD is computationally expensive—with explicit representation of sufficient water molecules to minimally solvate the folding chain, a nanosecond MD simulation of a 100-residue protein takes ~400 h on a current single processor. Advances in simulation strategy and increases in available computer power have considerably extended simulation times; for example, Kollman and coworkers carried out a microsecond simulation of a 36-residue peptide using a considerable amount of supercomputer time (Lee, Baker, and Kollman, 2001a). However, simulating the folding of a 100-residue protein for the typical ~1 s required for a single folding transition will require more than six orders of magnitude more computing time. The second, and perhaps more serious, class of problems associated with MD are the inadequacies in current potential functions for macromolecules in water. While important progress has been made, there is still a lack of consensus as to the best computationally tractable yet physically realistic model for water (a number of quite different models for water, both polarizable and nonpolarizable, have been used in current simulation methods) and some uncertainty in the values of the parameters used in molecular mechanics potentials (partial atomic charges, Lennard-Jones well depths, and radii). Accurate representation of electrostatics is also a considerable challenge given the high degree of polarizability of water; there is a large difference in the dielectric properties of the solvent and the protein, and the uncertainties in the magnitude and location of atomic charges density contribute to the error of calculations. Because the free energy of a protein represents a delicate balance of large and opposing contributions, these problems significantly reduce the likelihood that the native state will be found at the global free energy minimum using current potentials (Badretdinov and Finkelstein, 1998). The best current use of MD methods may be in refining and discriminating among models produced by lower resolution methods (Vejda, Lazaridis, Kollman and Lee, personal communication) (Lee, Duan, and Kollman, 2000).

The Balance Between Resolution and Sampling, Prospects for Improved Accuracy and Atomic Detail

As evident by the description of MD above, every de novo structure prediction procedure must strike a delicate balance between the computational efficiency of the procedure and the level of physical detail used to model protein structure within the procedure. Low-resolution models can be used to predict protein folds and sometimes suggest function (Bonneau et al., 2001b). Low-resolution models have also been remarkably successful at predicting features of the folding process, such as folding rates and phi values (Alm and Baker, 1999a; Alm and Baker, 1999b). It is clear, however, that modeling proteins (and possibly bound water and other cofactors) at atomic detail and scoring these higher resolution models with physically derived detailed potentials is a needed development if higher resolution structure prediction is to be achieved.

Initial focus was on the use of low-resolution approaches for searching the conformational landscape followed by a refinement step where atomic detail and physical scoring functions are used to select and/or generate higher resolution structures. This is a practical methodological mix when one considers the vastness of the conformational landscape and has resulted in good predictions in many cases. For example, several studies have illustrated the usefulness of using de novo structure prediction methods as part of a two-stage process in which low-resolution methods are used for fragment assembly and the resulting models are refined using a more physical potential and atomic detail (e.g., rotamers) (Dunbrack, 1997) to represent side chains (Bradley et al., 2003; Tsai et al., 2003; Misura and Baker, 2005). In the first step, Rosetta is used to search the space of possible backbone conformations with all side chains represented as centroids. This process is well described and has well-characterized error rates and behavior. High-confidence or low-scoring models are then refined using potentials that account for atomic detail such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatics.

One major challenge that faces methods attempting to refine de novo methods is that the addition of side-chain degrees of freedom combined with the reduced length scale (reduced radius of convergence; one must get much closer to the correct answer before the scoring function recognizes the conformation as correct) of the potentials employed requires the sampling of a much larger space of possible conformations. Thus, one has to correctly determine roughly twice the number of bond angles to a higher tolerance if one hopes to succeed. An illustrative example of the difference in length scale (radius of convergence) between low-resolution methods and high-resolution methods is the scoring of hydrogen bonds. In the low-resolution Rosetta procedure, backbone hydrogen bonding is scored indirectly by a term designed to pack strands into sheets under the assumption that correct alignment of strands satisfies hydrogen bonds between backbone atom along the strand and that intrahelix backbone hydrogen bonds are already well accounted for by the local structure fragments. This low-resolution method first reduces strands to vectors and then scores strand arrangement (and the correct hydrogen bonding implicit in the relative positions/arrangement of all strand vector pairs) via functions dependent on the angular and distance relationships between the two vectors. Thus, the scoring function is robust to a rather large amount of error in the coordinates of individual electron donors and acceptors participating in backbone hydrogen bonds (as large numbers of residues are reduced to the angle and the distance between the two vectors representing a given pair of strands). In the high-resolution, refinement, mode of Rosetta, an empirical hydrogen bond term with angle and distance dependence between individual electron donors and acceptors is used (Rohl, 2005). This, more detailed hydrogen bond term has a higher fidelity and a more straightforward connection to the calculation of physically realistic energies (meaningful units) but requires more sampling, as smaller changes in the orientation of the backbone can cause large fluctuations in computed energy.

Another major challenge with high-resolution methods is the difficulty of computing accurate potentials for atomic detail protein modeling in solvent. Currently, electrostatic and solvation terms are among the most difficult terms to accurately model. Full treatment of the free energy of a protein conformation (with correct treatment of dielectric screening) is complicated by the fact that some waters are detectably bound to the surface of proteins and mediate interactions between residues (Finney, 1977). Another challenge is the computational cost of full treatment of electrostatic free energy by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann or linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equations for large numbers of conformations. In spite of these difficulties, several studies have shown that refinement of de novo structures with atomic detail potentials can increase our ability to select and/or generate near-native structures (Neves-Petersen and Petersen, 2003). These methods can correctly select near-native conformations from these ensembles and improve near-native structures but still rely heavily on the initial low-resolution search to produce an ensemble containing good starting structures (Lee et al., 2001; Tsai et al., 2003; Misura and Baker, 2005). Some recent examples of high-resolution predictions are quite encouraging, and an emerging consensus in the field is that higher resolution de novo structure prediction (structure predictions with atomic detail representations of side chains) will begin to work if sampling is dramatically increased.

Progress in high-resolution structure prediction will invariably be carried out in parallel with methods including, but not limited to, predicting protein-protein interactions, designing proteins, and distilling structures from partially assigned experimental data sets. Indeed many of the scoring and search strategies that high-resolution de novo structure refinement methods employ were initially developed in the context of homology modeling and protein design (Kuhlman et al., 2002; Rohl et al., 2004a).

Clustering: A Heuristic Approach to Approximating Entropic Determinants of Protein Folding

Several protein structure prediction methods are effectively two-step procedures involving the generation of large ensembles of conformations (each being the result of a minimization or simulation) followed by the clustering of the generated ensemble to produce one or more cluster centers that are taken to be the predicted models. Individual conformations are considered in the same cluster if their RMSD (root-mean-square distance) is within a given cutoff. Regardless of how one justifies the use of clustering as a means of selecting small numbers of predictions or models from ensembles of decoys conformations, the justification is indirectly supported by the efficacy of the procedure and the resultant observation that clustering has become a central, seemingly required, feature of successful de novo prediction methods. Starting with CASP3, the field has witnessed a proliferation of clustering methods as postsimulation processing steps in protein structure prediction methods (Simons et al., 1999a; Bonneau et al., 2002; Hung and Samudrala, 2003; Zhang and Skolnick, 2004).

Prediction of protein structure de novo using Rosetta relies heavily on a final clustering stage. In the first step, a large ensemble of potential protein structures is generated, and each conformation being the result of an extensive Monte Carlo search designed to minimize the Rosetta scoring function (see Table 32.1). Clustering is then applied, and the clusters are ranked according to size. The tightness of clustering in the ensemble is also used as a measure of method success. Larger tight clusters indicate a higher probability that the method produced correct fold predictions for a given protein. Representatives from each cluster are chosen that are called cluster centers.

Each Rosetta simulation involving Monte Carlo runs can be thought of as a fast quench starting from a random point on the conformational landscape. Many of these individual simulations results in incorrect conformations that score nearly as well as any correct conformations generated in the full ensemble of decoy conformations, as judged by the Rosetta score. A number of other potentials tested also lack discriminative power at this stage. This lack of discrimination by de novo scoring functions is partially the result of inaccuracies in the scoring function, limitations in our ability to search the landscape, and the fact that entropic terms are a major contributor to the free energy of folding. In any case, this lack of discrimination is mitigated by the final clustering step, and it has been shown that the centers of the largest clusters in a clustered Rosetta decoy ensemble are in most cases the conformations closest to native.

The ubiquitous use of clustering can be justified in several ways: (1) Clustering can be thought of as a heuristic way to approximate the entropy of a given conformation given the full ensemble of decoy conformations generated for a given protein. (2) Clustering can be thought of as a signal averaging procedure, averaging out errors and noise in the low-resolution scoring function (3) Clustering can be thought of as taking advantage of foldable protein specific energy landscape features such as broad energy wells that are the result of proteins evolving to be robust to sequence and conformational changes from the native sequence or structure (a mix of sequence and configurational entropy) (Shortle, Simons, and Baker, 1998).

An interesting alternative to the strategy of clustering ensembles of results from independent minimizations is the use of replica exchange methods. These methods employ large numbers of simulations spanning a range of temperatures (defined physically if one uses a physical potential or simply as a constant in the exponent of the Boltzmann equation for probabilistic scoring functions). These independent simulations are carried out in parallel and are allowed to exchange temperatures throughout the run. This simulation strategy ideally allows for a random walk in energy space (and thus better sampling) and can be used to calculate entropic term ex post facto. Replica exchange Monte Carlo has been used successfully in the simulation and prediction of protein structure and is interesting due to its explicit connection to a physical description of the system and its ability to search low-energy states without getting trapped (Okamoto, 2004).

CASP: EVALUATION OF STRUCTURE PREDICTIONS

In general, the most effective methods for predicting structure de novo depend on parameters ultimately derived from the PDB. Several methods use the PDB directly to estimate local sequence and even explicitly use fragments of local sequence from the PDB to build global conformations. These uses of the PDB require that methods be tested using structures not present in the sets of protein structures used to train these methods (or present in the sets of structures used to predict local structure fragments). For these reasons, the CASP, a biannual community-wide blind test of prediction methods, was conceived and implemented (Benner, Cohen, and Gerloff, 1992; Barton and Russell, 1993; Fischer et al., 1999). The first such evaluation of structure predictions showed that published estimates of prediction error were smaller than prediction error measured on a set of novel proteins outside the training set. This is not surprising given the difficulty of avoiding overfitting is as complex a data space as protein structure (Lesk, 1997). Indeed, early experiments showed that no methods for de novo structure prediction were effective outside of carefully chosen benchmarks containing only the smallest proteins. Spurred on by these early evaluations, the field returned to the drawing board and produced multiple methods with much higher accuracies in the new folds or de novo category (Moult et al., 1999; Murzin, 1999; Orengo et al., 1999a). Thus, the CASP experiments proved to be invaluable to the field at that point in the development of the field, provoking a renewed interest in the de novo structure prediction and properly realigned interest in techniques according to effectiveness.

Arguably, CASP has the flaw that experts are allowed to intervene and manually curate their predictions prior to submission to the CASP evaluators. Thus, the results of CASP are a convolution of (1) the art of prediction (each group’s intuition and skill using their tools) and (2) the relative performance of the core methods (the performance of each method in an automatic setting). Although this convolution reflects the reality when researchers aim to predict proteins of high interest, such as proteins involved in a specific function or proteins critical to a given disease or process being experimentally studied, it does not reflect the demands placed on a method when trying to predict whole genomes, where the shear number of predictions does not allow for much manual intervention. Several additional tests similar to CASP (in that they are blind tests of structure prediction) have been organized in response to the concerns of many that it is important to remove the human aspects of CASP. The critical assessment of fully automatic structure prediction (CAFASP) is an experiment running parallel with CASP that aims to test fully automated methods’ performance on CASP targets, mainly testing servers instead of groups (Fischer et al., 1999; Fischer et al., 2003).

Several groups have also raised concerns that there are problems associated with the small numbers of proteins tested in each CASP experiment, and thus EVA and LiveBench were organized to test methods using larger numbers of proteins (Bujnicki et al., 2001; Rost and Eyrich, 2001; Rychlewski and Fischer, 2005). Both use proteins that have structures that are unknown to the participating prediction groups but that have been recently submitted to the PDB and are not open to the public at the time their sequences are released to those participating in LiveBench or EVA. The participating groups then have the time it takes for the new PDB entries to be validated to predict the structures.

All four of these tests of prediction methods, as well as benchmarks carried out by authors of any methods in question, are valuable ways of judging the performance of de novo methods. The methods, and elements of methods, we described above are generally accepted to be the best performers by the five above measures (four blind tests and author benchmarks).

BIOLOGICAL APPLICATIONS OF STRUCTURE PREDICTION

The Role of Structure Prediction in Biology

The main application of protein structure prediction is an open question that will take many years to develop. The answer depends on the relative rate of progress in several fields. We, however, consider that the most fruitful application of structure prediction in biology lies in understanding protein function and the ability to understand protein function on a genome scale. Structure predictions can offer meaningful biological insights at several functional levels depending on the method used for structure prediction, the resolution of the prediction, and the comprehensiveness or scale on which predictions are available for a given system.

At the highest levels of detail/accuracy (comparative modeling), there are several similarities between the uses of experimental and predicted protein structure and the types of functional information that can be extracted from models generated by both methods (Baker and Sali, 2001). For example, experimentally determined structures and structures resulting from comparative modeling can be used to help understand the details of protein function at an atomic scale. They can also be used to map conservation and mutagenesis data onto a structural framework and explore detailed functional relationships between proteins with similar folds or active sites.

At the other end of the prediction resolution spectrum, de novo structure prediction and fold recognition methods produce models of lower resolution than comparative models. These models can be used to assign putative functions to proteins for which little is known (Bonneau et al., 2001b). At the most basic level, we can use structural similarities between a predicted structure and known structures to explore possible distant evolutionary relationships between query proteins of unknown function and other well-studied proteins for which structures have been experimentally determined. A query protein is likely to share some functional aspects with proteins in the PDB that show strong structure-structure matches to a predicted structure with high confidence for that protein. This is based on the assumption that detectable structure relationships are conserved across a greater evolutionary distance than are detectable through sequence similarities. This assumption is well supported by multiple surveys of the distributions of folds and their related functions in the PDB (Murzin et al., 1995; Holm and Sander, 1997; Lo Conte et al., 2002; Orengo, Pearl, and Thornton, 2003). Promising preliminary results have been obtained with the approach of matching known structures to models produced by Rosetta: Dali, a server that compares structure through multiple structure alignments, frequently matches Rosetta models to protein structures related to the native structure for the sequence (Holm and Sander, 1993; Holm and Sander, 1995; Holm and Sander, 1997). The relationship between fold and function, however, is by no means a simple subject, and we refer the reader to several works that discuss this relationship in greater detail (Martin et al., 1998; Orengo, Todd, and Thornton, 1999b; Zhang et al., 1999; Kinch and Grishin, 2002).

A second way of exploring the functional significance of high-confidence predicted structures is to use libraries of three-dimensional functional motifs to search for conserved active site or functional motifs on the predicted structures (Moodie, Mitchell, and Thornton, 1996; Wallace et al., 1996; Fetrow and Skolnick, 1998).

Third, structures may be used to increase the reliability of matches to sequence motif libraries such as PROSITE—Taylor and Thornton’s groups have shown that structural consistency can be used quite effectively to filter through weak sequence matches to PROSITE patterns (Martin et al., 1998; Kasuya and Thornton, 1999).

These basic methods, fold-fold matching, the use of small three-dimensional functional motif searches, and increasing confidence of motif searches, can in principle be combined to form the basis for deriving functional hypothesis from predicted structure, and thereby extending the completeness of genome annotations based only on primary sequence.

Structure Prediction as a Road to Function

The relationship between protein structure and protein function is discussed in detail in other reviews but will be reviewed briefly here in the context of de novo structure prediction. One paradigm for predicting the function of proteins of unknown function in the absence of homologues, sometimes referred to as the “sequence-to-structure-to-structure-to-function” paradigm, is based on the assumption that three-dimensional structure patterns are conserved across a much greater evolutionary distance than recognizable primary sequence patterns (Fetrow and Skolnick, 1998). This assumption is based on the results of several structure-function surveys that show that structure similarities (fold matches between different proteins in the PDB) in the absence of sequence similarities imply some shared function in the majority of cases (Holm and Sander, 1997; Martin et al., 1998; Orengo, Todd, and Thornton, 1999b; Lo Conte et al., 2000; Todd, Orengo, and Thornton, 2001). One protocol, alluded to above, for predicting protein function based on this observation is to predict the structure of a query sequence of interest and then use the predicted structure to search for fold or structural similarities between the predicted protein structure and experimentally determined protein structures in the PDB or a nonredundant subset of the PDB (Holm and Sander, 1993; Murzin et al., 1995; Ortiz, Strauss, and Olmea, 2002; Orengo, Pearl, and Thornton, 2003). There are several problems associated with deriving functional annotation from fold similarity; for example, fold similarities can occur through convergent evolution and thus have no functional implications. Also, aspects of function can change throughout evolution leaving only general function intact across a given fold superfamily (Rost, 1997; Grishin, 2001; Kinch and Grishin, 2002). Fold matches between the predicted structures and the PDB are thus treated as sources of putative general functional information and are functionally interpreted primarily in combination with other methods, such as global expression analysis and the predicted protein association network. To circumvent these ambiguities one can (1) use de novo structure prediction and/or fold recognition to generate a confidence-ranked list of possible structures for proteins or protein domains of unknown function, (2) search each of the ranked structure predictions against the PDB for fold similarities and possible three-dimensional motifs (3) calculate confidences for the fold predictions and three-dimensional motif matches and finally (4) evaluate possible functional roles in the context of the other systems biology data, such as expression analysis, protein interactions, metabolic networks, and comparative genomics.

Genome Annotation

To date, the annotation of protein function in newly sequenced genomes relies on a large array of tools based ultimately on primary sequence analysis (Altschul et al., 1997; Brenner, Chothia, and Hubbard, 1998; Tatusov et al., 2003; Bateman et al., 2004). These tools have afforded great progress in genome annotation including large improvements in gene detection, sequence alignment, and detection of homologous sequences across genomes as well as the creation of databases of common protein families and primary sequence functional motifs. Comparative modeling methods have been highly successful on many fronts, creating large databases of highly accurate structure predictions for many organisms, but are based on primary sequence matches between PDB and query sequences (Pieper et al., 2002). Primary sequence methods also exist for the prediction of basic local structure qualities (some of these patterns being lower complexity patterns) of sequences such as the location of coiled coil, transmembrane, and disordered regions (Sonnhammer, von Heijne, and Krogh, 1998; Jones, 1999; Nielsen, Brunak, and von Heijne, 1999; Ward et al., 2004).

However, there are many factors that reduce the ability of sequence homology searches to identify distant homologues (Russell and Ponting, 1998). Domain insertions and extensions, circular permutations, and the exchange of secondary structure elements have all been observed in cases where structural and functional relationships were not clear based on sequence homology. To reliably interpret the flood of sequence information currently entering databases, we must have at our disposal methods that can deal with these difficult cases as well as the clearer evolutionary relationships detectable at the sequence level. One recently solved genome (Mycoplasma genitalium) showed sequence homology to proteins of known function and/or structure for 38% of its proteins (Rychlewski, Zhang, and Godzik, 1998). For S. cerevisiae, approximately one-thirds of the open reading frames (ORFs) in the genome show homology to proteins of known structure. Annotation of ORFs lacking sequence homology to proteins of known function represents one of the most promising potential uses for de novo prediction. Current methods can make reasonable predictions for small alpha and alpha-beta proteins, and the Rosetta method in particular has been successful in blind tests and extensively used in house tests on this class of proteins. Of the ~6000 ORFs in bakers yeast, ~300 have at least 15% of their residues predicted to be helical with a total length less than 110 residues and no link to proteins of known structure (220 of these 300 also lack functional annotation) (Mewes et al., 2000). Note that these figures exclude transmembrane proteins, which are still out of reach for most structure prediction methods. Models can also be produced for modular domains of up to ~ 150 residues that occur in sufficiently diverse sequence contexts for their boundaries to be readily evident from multiple sequence alignments.

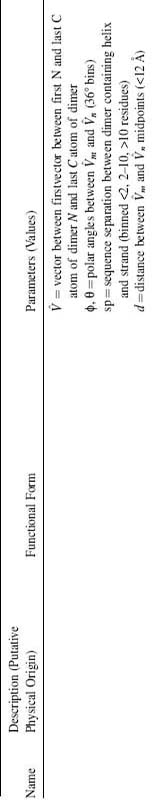

Efforts to use de novo structure prediction (and/or fold recognition) for genome annotations efforts must still employ sequence-based methods, as they provide a solid foundation on which all de novo methods discussed herein are reliant (see Figure 32.4). Any organization of these methods into an annotation pipeline must properly account for the fact that the accuracy/reliability is quite different between sequence and structure-based methods. One approach is to use structure prediction as part of a hierarchy where methods yielding high-confidence results are exhausted prior to computationally expensive and less accurate de novo structure prediction and fold recognition (Bonneau et al., 2004).

The need for methods that predict transmembrane protein structures and understanding membrane-protein interactions is not discussed in this chapter. The focus here is instead on soluble domains (including soluble domains excised from proteins containing transmembrane regions). Please refer to Chapter 36 for a more detailed discussion about research advances in this area. Part of the difficulty in predicting transmembrane protein structure lies in the paucity of membrane protein structures deposited on the PDB (Sonnhammer, von Heijne, and Krogh, 1998; Deshpande et al., 2005). Again, it is only with access to the PDB, an ideal and comprehensive gold standard by many criteria, that we can approach the problem of predicting soluble protein structure on a genome-wide scale.

Data Integration as a Means of Improving Structure Prediction Coverage and Error Rate

Genome-wide measurements of mRNA transcripts, protein concentrations, protein-protein interactions, and protein-DNA interactions generate rich sources of data on proteins, both those with known and those with unknown functions (Baliga et al., 2002; Baliga et al., 2004).

Figure 32.4. Structure annotation pipeline: Sequences enter the pipeline at the top of this figure, where they go through the masking of low-complexity regions such as transmembrane helices, signal peptides, and disordered regions. The resulting sequence (that not masked by step 1) is passed to Ginzu, a domain prediction pipeline (starting with PSIBLAST to PDB).

These systems-level measurements seldom suggest a unique function for a given protein of interest, but often suggest their association with or perhaps their direct participation in a previously known cellular process. Investigators using genome-wide experimental techniques are thus routinely generating data for proteins of hitherto unknown function that appear to play pivotal roles in their studies.

The first full-genome applications of de novo structure prediction was to the genome of Halobacterium NRC-1 (Bonneau et al., 2004). This archaeon is an extreme halophile that thrives in saturated brine environments such as the Dead Sea and solar salterns. It offers a versatile and easily assayed system with several well-coordinated physiologies that are necessary for survival in its harsh environment. The completely sequenced genome of Halobacterium NRC-1 (containing ~2600 genes) has provided insights into many of its physiological capabilities; however, nearly half of all genes encoded in the halobacterial genome had no known function prior to reannotation (Rost and Valencia, 1996; Devos and Valencia, 2000; Ng et al., 2000; Devos and Valencia, 2001). A multiinstitutional effort is currently underway to study the genome-wide response of Halobacterium NRC-1 to its environment, elevating the need for applying improved methods for annotating proteins of unknown function found in the Halobacterium NRC-1 genome. Rosetta de novo structure prediction was used to predict three-dimensional structures for 1185 proteins and protein domains (<150 residues in length) found in Halobacterium NRC-1. Predicted structures were searched against the PDB to identify fold matches (Ortiz, Strauss, and Olmea, 2002) and were analyzed in the context of a predicted association network composed of several sources of functional associations such as predicted protein interactions, predicted operons, phylogenetic profile similarity, and domain fusion. This annotation pipeline was also applied to the recently sequenced genome of Haloarcula marismortui with similar rates of correct fold identification.

An application of de novo structure prediction to yeast has also been described (Malmstrom et al., 2007). This study focused on the application and integration of several methods (ranging from experimental methods to de novo structure prediction) to 100 essential open reading frames in yeast (Hazbun et al., 2003). For these 100 proteins, the group applied affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry (to detect protein binding partners), two-hybrid analysis, fluorescence microscopy (to localize proteins), with de novo structure prediction—Ginzu to separate domains (Chivian et al., 2003; Kim, Chivian, and Baker, 2004) and Rosetta to build structures for domains of unknown function. Due to the cost of experiments and the computational cost of Rosetta de novo structure prediction, the group was initially able to prototype the method on just these 100 proteins. Function was assigned to 48 of the proteins (as defined by assignment to Gene Ontology categories). In total, 77 of the 100 proteins were annotated (had confident hits) by the methods employed. Given that the starting set represented a difficult set of ORFs of no known function, this represents a significant milestone (Malmstrom et al., 2007).

Scaling this sort of approach up to whole genomes (including large eukaryotic genomes) is still a significant challenge. A grid computing solution (described below) has been employed to complete this study and fold the remaining ORFs in the yeast genome. Of 14934 domains parsed from yeast proteins, 3338 domains were folded with Rosetta and 581 were annotated with SCOP superfamilies. SCOP superfamilies were assigned using a Bayesian approach that integrated Gene Ontology annotations of process, component, and function. Also, 7094 domains were assigned structural annotation using homology modeling and fold recognition. Due to the wide use of yeast as a model organism, we can expect this complete resource to be a major step in crossing the social and technical barrier that has so far prevented the wide application of de novo structure prediction to biology. (Malmstrom et al., 2007)

A similar approach has also been applied to the Y chromosome of Homo sapiens (Ginalski et al., 2004). By integrating fold recognition with de novo structure, prediction folds were assigned to ~42 of the 60 recognized domains examined (these 60 domains originated from the 27 proteins thought to be encoded on this chromosome at the time of the study). In both these application, yeast and human, careful thought was put into reducing the set of proteins examined, and scaling up de novo structure prediction remains a critical bottleneck (the introduction of all-atom or high-resolution refinement of these predicted structures will only exacerbate this critical need for computing).

The Human Proteome Folding Project: Scaling up De Novo Structure Prediction, Rosetta on the World Community Grid

There are several strategies one can use to limit the number of protein domains for which computationally expensive de novo structure prediction needs to be carried out, allowing for the calculation of useful de novo structure predictions for only the most relevant subsets of larger genomes, as discussed above. In spite of these strategies, finding the required compute resources has been a constant challenge for the application of de novo structure prediction to functional annotation and has limited the application of the method. To circumvent this problem, we are currently applying a grid, distributed computing, solution to folding over 100,000 domains with the full Rosetta de novo structure prediction protocol (worldcommunitygrid.org). These domains were chosen by applying Ginzu (Chivian et al., 2003; Kim, Chivian, and Baker, 2004) to over 60 complete genomes as well as several other appropriate sequences in public sequence databases. The results will be integrated with data types that are appropriate/available for a given organism in collaboration with several other groups (Hazbun et al., 2003; Bonneau et al., 2004). This work is ongoing in collaboration with David Baker, Lars Malmstroem (University of Washington), Rick Alther, Bill Boverman and Viktors Berstis (IBM), and United Devices (Austin, TX). Currently, there are over a million volunteers (people who have downloaded the client to run grid Rosetta) comprising a virtual grid of over 3 million devices. Interested parties wishing to participate (donate idle CPU time on your desktop computer to this project) can download the grid-enabled Rosetta client at worldcommunitygrid.org. This amount of computational power will enable us to remove the barrier represented by the computational cost of de novo methods.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Structure Prediction and Systems Biology, Data Integration

Even with dramatically improved accuracy, we still face challenges due to the ambiguities of the relationship between fold and function seen for many fold families (indeed even close sequence homology is not always trivial to interpret as functional similarity). Thus, the full potential of de novo structure prediction in a systems biology context can only be realized if structure predictions are integrated into larger analysis and subsequently made accessible to biologists through better data integration, analysis, and visualization tools. One clear example of this is provided by the bacterial transcription factors for which even strong sequence similarity can imply several possible functions, and system-wide information is required to determine a meaningful function (the target of a given transcription factor).

Need for Improved Accuracy and Extending the Reach of De Novo Methods