34

STRUCTURAL BIOINFORMATICS IN DRUG DISCOVERY

The pharmaceutical industry had its origins in the beginning of the twentieth century. Scientific advancement has since seen the discovery of DNA and sequencing of the human genome, the understanding of proteins as specific molecular entities, the harnessing of X-rays to understand proteins at the atomic level, and the introduction of computational technology. All these advancements have allowed structural bioinformatics to begin to do its part to further aid drug discovery. This chapter will take a brief look at the development of the drug discovery process before discussing the current and future role of structural bioinformatics in this context.

HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT OF DRUG DISCOVERY

The current dominant paradigm the pharmaceutical drug discovery follows is to search for a particular small-molecule modulator of a specific macromolecular target. A protein with a known or a suspected role in a disease process is selected and small-molecule modulators of the protein are identified and optimized. Our ability to pursue this paradigm rests on the scientific and technological achievements of the twentieth century, particularly with regard to our ability to manipulate organic small molecules on the one hand and to study the biological targets on the other (Drews, 2000). Humanity has, of course, been looking for remedies for its ailments long before there was a drug discovery industry (Sneader, 1995; Sneader, 2005). The use of willow bark as a treatment for pain relief, for example, can be traced back to Hippocrates and earlier. Such use is entirely empiric—a certain recipe gave relief to certain symptoms. Many such folk remedies were known, the progeny of some of which, such as willow bark, have found their place in our modern medicine chests.

The first step toward our modern approach to drug discovery was the suggestion that these remedies generally contained an active ingredient that could be isolated and purified. This idea can be traced back to 1530 to Paracelsus, a Swiss physician; however, the active ingredient salicin in willow bark could not be purified until 1829, another 300 years later. The synthesis of urea by Fredrich Wohler the year before ushered in organic synthesis and gave chemists the ability to manipulate small organic compounds of this type. Salicylic acid itself was first synthesized in 1852. Along with the power to create a specific molecule came the ability to create many closely related compounds. These techniques were first put to profitable use in the dye industry in the mid-1800s, creating for the first time numerous low-cost dye compounds.

Using such dyes for histological staining, Paul Ehrlich recognized that related molecules often exhibit related biological effects, a concept referred to today as structure-activity relationships (SAR). This concept was applied to derivatives of salicylic acid to try and discover forms of the drug that were less unpleasant for the patient. This research eventually led to the development of acetylsalicylic acid in 1897 by Felix Hoffmann at Bayer. Bayer named this compound Aspirin: “a” for acetyl, “spir” from Spiraea ulmaria, the meadowsweet plant, and “in” a common suffix for medicines at the time. In noticing how some compounds more readily stained bacterial cells than human cells, Paul Ehrlich eventually developed another major cornerstone of modern drug discovery, the concept of a therapeutic index. All drugs have a minimal dose at which they demonstrate beneficial effects and a minimal dose at which they demonstrate harmful effects. The therapeutic index is simply the ratio of these two doses.

The interplay between trying to make compounds more effective and keeping drugs safe for use continues to be at the center of pharmaceutical discovery till date. The recognition of activity being associated with specific molecular entities was paralleled (much later) by John Langley’s suggestion in 1878 that there must be specific “receptors” for such compounds in the host, which bind to these entities. Knowing that there is a host receptor however is not the same as knowing what that receptor is. It would be another 100 years, for example, before John Vane and his colleagues discovered the link between aspirin and prostaglandin synthesis, establishing cyclooxygenase (COX) as aspirin’s site of action (Vane, 1971). This work earned John Vane the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. Cyclooxygenase was first given a structural face by Michael Garavito and colleagues in 1994 (Picot, Loll, and Garavito, 1994). This structure, and that of the inducible COX-2 (Kurumbail et al., 1996; Luong et al., 1996), have made possible the first forays into structure-based design against this venerated target (Marnett and Kalgutkar, 1999). Recognition of different isoforms of cyclooxygenase (Vane et al., 1994) and their roles has led us to specific COX-2 inhibitors, such as Celecoxib (Penning et al., 1997), with reduced side effects of peptic ulcers compared to early COX inhibitors. The story does not have its happy ending however, with evidence pointing to an increase in frequency of undesirable cardiovascular effects with COX-2 inhibitors (Kearney et al., 2006).

MODERN DRUG DISCOVERY

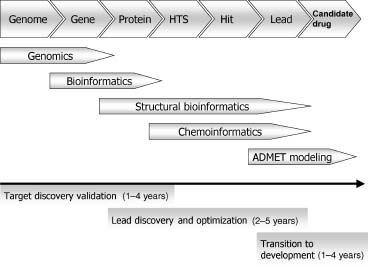

At present, most pharmaceutical drug discovery programs begin with a known macromo-lecular target, and seek to identify a suitable small-molecule modulator (Rang, 2005). The process is depicted in Figure 34.1. Typically, the target (usually a protein) has already been identified, through biological or genetic investigations, to be important in the disease of interest. The approach of modern drug discovery is rational and reductionistic with a defined hypothesis of how the chosen mechanism of action could be beneficial against disease. Following the identification of the target of interest, confidence in the approach is built with a variety of genetic and chemical target validation experiments.

Figure 34.1. The role of informatics in the target-based drug discovery process.

The process to discover a lead molecule begins with the development of an assay to look for modulators (inhibitors, antagonists, or agonists) of the target’s activity, followed by a high-throughput screen (HTS) of a large number of small molecules, in some cases several millions (Fox et al., 2006; Macarron, 2006). This may seem like a very large number of molecules but there are an estimated 1060-10200 possible organic small molecules (Bohacek, Martin, and Guida, 1996; Weininger, 1998; Gorse, 2006; Fink and Reymond, 2007). Therefore, even with a HTS collection of 106, one cannot hope to “cover chemical space” in any meaningful way. However, HTS campaigns are occasionally successful pointing perhaps to the promiscuity of protein binding sites. In the best cases, this method identifies one or more small-molecule “hits” in the micromolar range, that is, for a competitive inhibitor, having binding constants, often expressed as Ki’s or IC50’s from 10 micromolar to the low nanomolar range. Medicinal chemistry is then applied to elaborate the initial small molecule to improve the potency, ideally lowering the Ki to the low nanomolar range to produce a potent lead molecule (Foye, 1989).

The process of optimizing the lead molecule into a “candidate” drug is often the longest and most expensive preclinical stage in the drug discovery process (although this is still a fraction of the costs of drug development). The candidate is usually an analogue of the original lead, but it is still considered an art to successfully synthesize and select the exact compound that fulfills all the required properties of potency, absorption, bioavailability, metabolism, safety, and, of course, efficacy. The lead-to-candidate stage of drug discovery is a multidimensional optimization problem, a search within the relatively limited chemical space of analogues of the lead compound (Chapter 27).

Following the selection of the candidate molecule, the drug development scientists develop large-scale production methods and conduct preclinical animal safety studies. investigational new drugs (INDs) must pass through a set of three clinical trials: Phase I, a small study on healthy subjects to confirm safety; Phase II, a slightly larger study on a patient population to confirm efficacy; and Phase III, a large study of patients to gather additional information about safety and efficacy (CDER Handbook, 1998). However, even after the medicinal chemist has carefully crafted and balanced the properties of potency, bioavailability, and metabolism, only 11% of the compounds entering clinical trials make it to market, most often failure is due to poor biopharmaceutical properties, toxicity, or lack of efficacy (Kola and Landis, 2004). Due to the attrition of so many potential pharmaceuticals and the rising costs of drug discovery, the average cost to bring each new chemical entity (NCE) to market in 2001 was estimated to be $804 million (DiMasi, Hansen, and Grabowski, 2003). This has caused many to reassess the approach taken by the pharmaceutical industry. Possible alternative approaches are briefly overviewed in the following sections.

Thus far, the discussion has focused on small-molecule drugs, that is, organic molecules of molecular weight of the order of hundreds of Daltons; however, the role of biological therapeutics, primarily enzymes and antibodies, should not be underestimated (Brekke and Sandlie, 2003; Adair and Lawson, 2005). Structural bioinformatics have a major impact in both areas; however, the focus of this chapter will primarily be on its role in developing small-molecule drugs that are NCEs with a known mode of action. However, this approach requires the availability of experimental macromolecular structures and we will therefore first address the generation of protein structures in a pharmaceutical context.

GENERATING PROTEIN STRUCTURES

The optimal structure-based drug design (SBDD) program involves repeated cycles of determining the structure of the target in complex with a number of lead compounds and their analogues (Congreave, Murray, and Blundell, 2005). One hurdle in establishing a rapid cycle of crystallography and structure-based design is, of course, obtaining crystals of the target protein of sufficient quality. A genetic construct encoding the exact full-length sequence of a protein is not necessarily the ideal strategy to use to obtain material for screening or structural studies. The reason being is that the full-length protein may be large and contain protein domains that are not relevant to the studies performed. The protein may also be poorly expressed, unfolded, or insoluble, and thus create challenges that preclude protein crystallization.

To avoid such problems, structural bioinformatics can be used to design suitable constructs. As described in Chapter 20 (domain assignments), proteins are frequently composed of discrete domains. The computational techniques of domain detection can be combined with experimental techniques of domain assignment (e.g., limited proteolysis followed by mass spectroscopy analysis). The designed constructs can be evaluated on the basis of their expression levels, solubility, activity, and crystallizability (Kim, Chivian, and Baker, 2004).

The selection of an appropriate domain for structural studies often begins by aligning the sequence of the target protein with that of a protein of known structure. One can then determine where it may be possible to truncate the protein at the amino- and carboxy-termini regions. Where structures are not available, secondary structure prediction can be used (see Chapter 19). Combining secondary structure prediction, based on multiple sequence alignments, with analysis of sequence conservation can be particularly successful. One can often express a protein from a construct designed to start and finish where sequence conservation is high and at the end of predicted elements of secondary structure. It should be noted that the same process could be used to guide construct design for the production of the target protein for HTS assays. In fact, in the best cases, the same construct can be designed for both screening and structural biology.

Rational construct design is now usually complemented with high-throughput, triage-type approaches to generate material for structural biology studies. Improvements in automation and analysis techniques allow a library of constructs to be designed and evaluated. Subsequently, the most promising constructs are pursued, while others are disregarded (Goh et al., 2004). Where no crystals or poor crystals are obtained, these can be modified to improve properties, applying the so-called crystal engineering (Derewenda, 2004).

As described in Chapter 4 (X-ray crystallography), a second hurdle in structure determination by crystallography is the so-called phase problem. One common solution to this problem is molecular replacement. In molecular replacement, a model representing some or all of the new protein is rotated and translated into the new unit cell in an attempt to find a solution. Originally, molecular replacement was only used for cases of a specific protein in different space groups or in cases of high sequence identity. Greater computational power, as well as the greater wealth of known folds, has resulted in molecular replacement being successfully applied even in cases where the starting model exhibited only 20% sequence identity or less (Storici et al., 1999; Hong et al., 2000).

The extent to which the core of a protein is distorted with greater sequence divergence (Chothia and Lesk, 1986) will presumably place a limit on when molecular replacement can be used. However, even when phases are determined experimentally (e.g., through heavy atoms or selenomethionine techniques), identification of a suitable structural homologue at even 10% sequence identity can greatly accelerate the interpretation of the electron density maps and of the protein structure (Bugl et al., 2000). Multiple homology models can be used instead of crystal structures in this context and they have provided structure solutions where the use of homologue structures has failed (Claude et al., 2004).

Most protein crystals are actually quite soft and contain a high proportion of water. Not only does this give us some confidence that many structures are representative of the protein in solution, but it also allows crystal structures of protein with ligands to be obtained, simply by soaking a pregrown crystal in a solution of the ligand of interest. This can be of great help in an iterative drug design cycle, where speed is very important; however, care must be taken to ensure that the soaking procedure does allow a ligand and protein to adopt relevant conformations.

When a particular target is inaccessible to structural biology, a project may rely on the use of a related protein for structure determinations. At the simplest, this situation may involve using the orthologous protein from another species or selecting a similar member of the same gene family. More complex uses are those where there is similarity at the structural and functional level that does not extend to sequence, for example, in the case of thermolysin and NEP (Holland et al., 1994).

DRUG TARGETS

Biological systems contain only four types of macromolecules with which we can interfere using small-molecule therapeutic agents: proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, and nucleic acids. Toxicity, specificity, and the difficulty in obtaining potent compounds againstthe latter three types mean that the majority of successful drugs achieve their activity by modifying the activity of a protein, usually by competing for a binding site on that protein with an endogenous small molecule. There have been a number of attempts to catalog the protein targets of known drugs (Drews, 1996; Drews and Ryser, 1997; Hopkins and Groom, 2002; Golden, 2003; Russ and Lampel, 2005; Imming, Sinning, and Meyer, 2006; Wishart, 2006; Zheng et al., 2006a; Zheng et al., 2006b), with several of these resulting in target databases.

A consensus survey of current drug targets for all therapeutic drug classes in the industry has now been arrived at and is reported by Overington (Overington, Al-Lazikani, and Hopkins, 2006). The 21,000 drugs captured in the U.S. FDA’s Orange Book and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) were reduced to 1357 unique drugs, of which 1204 are small-molecule drugs and 166 are biological agents. Targets were then assigned to 1065 of the compiled drugs (a far from trivial exercise), giving a number of just 324 drug targets for all classes of approved therapeutic drugs. This captures the molecular targets of all approved drugs to treat human disease, whether the target is of human origin or present in an infecting organism. When one considers proteins encoded by the human genome alone, targeted by small-molecule drugs, the figure is further reduced to 207.

Almost 70% of drug targets fall into just 10 protein families, with over 50% of drugs exerting their activity via 4 families. These families are class 1 GPCRs, nuclear receptors, ligand, and voltage-gated ion channels. Categorizing drug targets by their structural domains, using the CATH (Chapter 18), SCOP (Chapter 17), and PFAM databases, reveals that there are 130 “privileged druggable domains.” Of particular interest to the structural bioinformatician is the degree of structural characterization of drug targets. The PDB (see Chapter 11) contains structures of 105 drug targets, with over 92% (300/324) of targets having some structure in the PDB.

Drug Target Discovery

Structural bioinformatics plays an important role in “target-based” drug discovery. However, “traditional” approaches to drug discovery are still very much with us; indeed, many argue that such approaches remain the most cost-effective way of generating new medicines (Brown and Superti-Furga, 2003). Such approaches can be described as “letting the compounds choose the target” as opposed to identifying compounds to interact with preselected targets. The former approach has recently been rebranded as “chemical genetics” (Stockwell, 2000; Stockwell, 2004). Assays of direct functional relevance are chosen for such approaches and while knowledge of the molecular target can be helpful, it is certainly not essential. This is exemplified by the development of the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam, the molecular target of which was discovered sometime after the drug had demonstrated clinical efficacy (Lynch et al., 2004). Indeed, the precise molecular function of this target protein remains unknown.

The ability to test compounds in a wide variety of biological assays has also provided data that have led many to question the effectiveness of single target-led drug discovery programs (Hopkins, Mason, and Overington, 2006). As more “cross-screening” takes place, additional activities continue to be observed in what were once described as selective drugs (Paolini et al., 2006). The activity of compounds against multiple targets can sometimes be correlated with the sequence and structural similarity of those targets (Keiser et al., 2007).

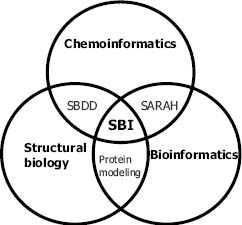

Informatics and knowledge-based methods play an important role in the framework of the postgenomic, target-based drug discovery paradigm, in support of screening and medicinal chemistry. The ability of chemoinformatics to process the properties of millions of virtual compounds for selection for synthesis and screening is an enabling technology for combinatorial chemistry and HTS. Biological structural information can be usefully exploited from the identification of the target protein to all the way to the design of a bioavailable drug. As depicted in Figure 34.2, structural bioinformaticians in a pharmaceutical company also serve to link resources and results stemming from bioinformatics, structural biology, chemoinformatics, and the structure-based drug design groups. The following sections will describe how structural bioinformatics can be employed to help make informed choices on which proteins to target to identify a molecule of medicinal benefit.

Figure 34.2. The relationship between structural bioinformatics (SBI) and other disciplines in drug discovery. Achievements from both structural biology and chemoinformatics yield methodology for structure-based drug design (SBDD). The interaction between bioinformatics and chemoinformatics can be exemplified with structure activity relationship and homology (SARAH) (Frye, 1999; Schafer and Egner, 2007). Protein modeling is at the interface between bioinformatics and structural biology.

Target Identification and Assessment

As structural inferences become available at the very earliest stages of a drug discovery program, structural bioinformaticians can provide a priori assessment of the ability of a target to be inhibited by a drug-like molecule. Designing compounds with appropriate biopharmaceutical properties that are still able to bind to their targets with an appropriate affinity is the challenge for the medicinal chemist. A current challenge for structural bioinformaticians is to determine the magnitude and difficulty of the medicinal chemists’ task to synthesize the molecule designed in silico.

The availability of the sequences from complete genomes has revealed many more potential targets than could possibly be pursued using current experimental technologies. As such, it is sometimes necessary to prioritize targets from a large potential subset that has been identified. Such a subset may arise, for example, from a gene expression study (Sallinen et al., 2000) by analyzing the genomes of disease-causing organisms (McDevitt and Rosenberg, 2001) or by assessing a particular metabolic or signaling pathway (Sivachenko and Yuryev, 2007). Properties of interest when considering large numbers of targets go beyond the assessment of the active site and include those summarized in Table 34.1. The pharmaceutical industry has had different degrees of success on various target families; this may be due to a number of these factors and has been discussed particularly for protein kinases (Groom and Hopkins, 2002).

TABLE 34.1. Considerations When Selecting Molecular Targets

| Property | Consideration |

| Confidence in rational | How strong is the evidence to indicate that modulating the activity of the target will produce the desired response? |

| Sense of modulation | Is inhibition or agonism necessary to correctly modulate disease process? Note that although GPCRs can effectively be turned on by agonists, this is difficult with most enzymes. |

| Ability to bind drug-like molecules | Does the target have the potential to recognize compounds with appropriate properties to a reasonable affinity? |

| Ease of screening | Can the target protein be obtained in quantities sufficient to facilitate high-throughput screening? |

| Availability of protein structure | Is an X-ray or NMR structure of the protein available to allow structure-assisted drug design? |

| Pathway | Is the target protein in a redundant signaling or metabolic pathway where it can be bypassed? |

| Potential for resistance | Do pathogens contain mutant isoforms of the target protein? |

| Availability of chemical Leads | Are there chemical leads available with suitable properties? |

| Selectivity | Are there related proteins (in the host) that might be affected by inhibitors against the target? |

A number of these factors can be analyzed computationally. For example, researchers at Bristol-Myers Squibb identified genes conserved across 10 fungal genomes, which may encode protein targets for antifungal therapies (Liu et al., 2006). Of the 1049 essential yeast genes, 240 had a homologue in all 10 species with a sequence identity of ≥40%. This level of similarity was chosen as the authors identified that the few known, broad-spectrum antifungal drugs targeted proteins with around this level of cross-species similarity. Ideal targets may be those that also had no human homologue, as this may minimize side effects, 41% of the target proteins fitted this criteria. This “concordance analysis” was used as the starting point for assays to both confirm the essentiality of these genes across the organisms of interest and to identify chemical hits.

The following section describes the characteristics of a binding site that may make a

particular protein target amenable to modulation by a small-molecule drug; however, one is not always

aware as to the location of the binding site or if indeed such a site exists. Fortunately, a number of

structure-based binding site (or pocket) prediction algorithms are available (Chapter 27) (An, Totrov,

and Abagyan, 2005; Glaser et al., 2006). Not only is it possible to identify drug binding pockets, but

also it is possible to compare them (Kuhn et al., 2006) and identify channels between pockets and to the

surface of a protein for which the small molecule can pass through (Pet ek et al., 2006).

ek et al., 2006).

Principles of Druggability

Not all small molecules can be drugs; similarly, not all proteins can be drug targets. A small molecule must have certain properties, and a protein must contain a binding site that is complementary or compatible with these properties. Binding sites on proteins usually exist out of functional necessity. Due to hydrophobic forces, the energetically optimal protein would be spherical, with all its hydrophobic residues pointing inward (see Chapter 2). As such, drug binding pockets seem to be quite rare, most of those identified to date exist out of functional necessity, that is, to bind an endogenous small molecule. Therefore, the majority of drugs achieve their activity by competing for a binding site on a protein with an endogenous small molecule. Drugs exploiting allosteric binding sites, with no known natural endogenous ligand, are relatively rare (e.g., the nonnucleoside binding site on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and some protein kinases) (Noble, Endicott, and Johnson, 2004), and these binding sites are usually not observed in the absence of the ligand, since they are generally transitory in nature.

Example: Kinases and Other ATPases. Examination of the natural ligands of a protein can be valuable in assessing the capacity of a binding site to bind a drug-like molecule. The numerous types of ATPases present an interesting example. By definition, ATP is a common cofactor for many enzymes. It is recognized by a number of protein folds in a variety of ways. The adenosine portion of ATP (the adenine and ribose rings) has properties one would expect to be able to mimic in a drug. In contrast, it would be difficult to mimic the three charged phosphate groups in a drug-like molecule, because charged compounds typically cannot penetrate cell membranes. Thus, when one is considering an ATPase as a potential target, it is helpful to determine the way in which the ATP is recognized.

In protein kinases, the adenine ring of ATP fits into a well-defined, relatively hydrophobic pocket, forming a number of important hydrogen bonds. The phosphate groups play a relatively minor role in this recognition (Johnson et al., 1998). It has proven to be relatively straightforward to generate potent, drug-like inhibitors of protein kinases that are competitive for ATP, making use of this attractive binding pocket (Bridges, 2001; Dumas, 2001). In ATPases that rely on coordination of the phosphate group and contains the so-called Walker A or B motif (Walker et al., 1982), for example, inhibition by drug-like molecules has proven difficult by and large; however, exceptional cases was noted with inhibitors bound to two such motifs (Wigley et al., 1991). In many cases, the exact structure of the ATPase may not be known. Even when the structural motif used to recognize ATP is not known, one can gain clues as to the attractiveness of the ATP site by inference from the binding affinities of ATP, ADP, AMP, adenosine, and adenine using biochemical information from the literature. Differences in dissociation constants in this series may allow one to predict which regions of ATP are important recognition features.

Example: Proteases. The proteases present additional subtleties involved in assessing the tractability of individual molecular targets. The substrates of proteases, that is, peptides, represent reasonable chemical leads for a drug discovery process. Crucial to success, however, is the ability to “depeptidize” these leads for peptidomimetic design. That is, to remove the peptide bonds to avoid absorption and metabolic stability issues. For some proteases, this is relatively straightforward. One example is the serine protease thrombin, where many drug-like inhibitors, barely resembling peptides, have been developed (Steinmetzer, Hauptmann, and Sturzebecher, 2001; Kwaan and Samama, 2004). In the case of the aspartyl protease renin, it has proven much more challenging to develop nonpeptidic inhibitors (Stanton, 2003), although the drug aliskiren has recently been developed and is probably the least peptidic and most promising renin drug (Wood et al., 2003).

When one analyzes the way in which substrates are recognized by these two types of proteases, the reasons become clear. Serine proteases typically recognize both main-chain and side-chain features in their substrates, forming hydrogen bonds to relatively few main-chain groups on only one side of the scissile bond. Aspartyl proteases are typically tolerant of side-chain substitutions in their substrates and rely on main-chain hydrogen bonds to bind their substrates. In this case, it has proven difficult to retain potency in an inhibitor while reducing the peptidic character of leads. This has also been the case for many viral proteases, where substrate peptides are often weakly bound in shallow pockets on the enzyme surface (Chen et al., 1996).

Protein families such as kinases and proteases are well-precedented drug targets. Choosing whether to target more novel targets or unusual binding sites is a crucial process, particularly for a small research group with limited resources. For nonprecedented targets, one can predict their druggability (Chapter 27) via a visual inspection of their binding sites. The following section describes how this important process can be carried out in a more automated and objective manner.

Quantitative Assessment of Druggability

The foregoing discussion assumes the opportunity to perform an in-depth, individual analysis of the relevant protein structures. For a quick assessment of a large number of potential targets, a more quantitative approach is more appropriate. Such a quantitative approach is already well established for assessing the drug-like properties of a small molecule. The rule-of-five (Table 34.2) is a set of properties applied to suggest which compounds are likely to show good oral bioavailability (Lipinski et al., 1997). Although not intended as such, the preference of the pharmaceutical industry for such compounds makes this a useful “rule of thumb” to describe drug-likeness. Only 20% of orally dosed small-molecule drugs fail the rule-of-five test (Overington, Al-Lazikani, and Hopkins, 2006).

Further work has refined what distinguishes drugs from other compounds. The reader is referred to relevant work (Ajay, Walters, and Murcko, 1998; Sadowski and Kubinyi, 1998; Gillet et al., 1999; Blake, 2000; Clark and Pickett, 2000; Lipinski, 2000; Walters and Murcko, 2002; Lajiness, Vieth, and Erickson, 2004; Vieth and Sutherland, 2006; Oprea et al., 2007).

Given that the properties of a drug are complementary to those of the binding site, analysis of the calculated physicochemical properties of the putative drug binding pocket on the target protein can provide an important guide to the medicinal chemist in predicting the likelihood of discovering a drug against the particular target site (Chapter 27). Equivalent rules have been developed to describe physicochemical properties of binding sites with the potential to bind rule-of-five compliant inhibitors with a potent binding constant (e.g., Ki < 100 nM). A number of properties complementary to the rule-of-five can be calculated; for example, the surface area and volume of the pocket, hydrophobic and hydrophilic character, and the curvature and shape of the pocket.

Programs such as SURFACE (Lee and Richards, 1971; CCP4, 1994), CAST (Liang, Edelsbrunner, and Woodward, 1998), MS (Connolly, 1993), and GRASP (Nicholls, Sharp, and Honig, 1991) can be used to calculate these and other parameters. Indeed, it has been shown that parameters such as these are quite predictive of the likelihood of a high-throughput screen to identify suitable chemical hits (Cheng et al., 2007). Experimental determination of druggability can be performed using NMR-based fragment binding assays (Hajduk, Huth, and Fesik, 2005a; Hajduk, Huth, and Tse, 2005b). Underlying these experiments and predictions is the concept of ligand efficiency (Hopkins et al., 2004), discussed in further detail in Section 6.1. This captures the concept that druggability relates to the amount of potential binding energy available in a binding site, as a function of the size of the site.

TABLE 34.2. The Rule-of-Five

| A compound is likely to show poor absorption or permeation if |

| It has more than five hydrogen bond donors |

| The molecular weight is over 500 |

| The Clog P (calculated octanol/water partition coefficient) is over five |

| The sum of nitrogens and oxygens is over 10 |

The computational predictions of druggability of the binding sites, as described above, are normally carried out on X-ray crystal structure treated as static coordinates. Of course proteins are not static entities and in the search for nonobvious druggable binding sites, their flexible nature is increasingly being taken into account.

Protein Flexibility and Drug Design

The plastic nature of biological molecules is well documented with corresponding flexibility and conformational changes (Chapter 38) shown to be important for biological function. Moreover, molecular recognition and complementarity is in itself a dynamic event. Certainly, the idea of a rigid receptor is now out of date (Teague, 2003). The degree in which one can explore this flexibility depends on the technology and information available. Recent advances in biological and structural techniques coupled with the increasing power of computation are enabling scientists to understand and predict flexibility in biological systems.

Binding site mobility can be thought of in two ways: conformational selection of protein targets or induced fit (Teague, 2003). In the former, the ligand enriches the equilibrium of protein conformers toward the one that fits the ligand best. In the induced fit model, the ligand binds and then the protein accommodates it. In the case of many synthetic drugs, which are often fairly hydrophobic and rigid molecules, binding is an entropically favorable process, often showing unfavorable enthalpy. The dogma is that this is disadvantageous because a drug is prone to lose affinity when the target protein mutates, due to normal drug resistance mechanisms or genetic polymorphisms (Teague, 2003). One can take advantage of protein mobility in ligand design and attempt to exploit allosteric sites. Allosteric sites are able to bind ligands, which shift the conformational equilibrium of the protein partners toward conformations that cannot function (Christopoulos, 2002). Exploring possible conformations of the protein can open new sites or expose new shapes for small molecules to bind, and there are a number of cases exemplifying this (Erlanson et al., 2000; Papadopoulos, 2006; Thanos, DeLano, and Wells, 2006; Toth, Mukhyala, and Wells, 2007).

Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions

We have seen in the previous sections how drug discovery has focused on a handful of targets that meet the classical druggable criteria: being linked to disease and having a “beautiful” pocket to which a small, drug-like molecule binds (Hopkins and Groom, 2002). In a recent review, Whitty and Kumaravel (2006) classified targets in terms of chemical and biological risk. The probability of finding a small molecule to modulate the target under evaluation is its chemical risk. The biological risk covers the therapeutic effect of its modulation. Classical drug targets, such as enzymes and GPCRs, present both low chemical and low biological risk. Although ubiquitous and pivotal to many biological processes, multiprotein complexes have not been considered to be in this class. However, due to their fundamental role in living organisms, their modulation is likely to be therapeutically relevant, thus they should have low biological risk. This has been confirmed by the successful development of antibody drugs modulating extracellular targets (Adair and Lawson, 2005).

In contrast, multiprotein complexes present high chemical risk. Classical hit identification campaigns have struggled to deliver small chemical starting points for protein-protein interaction (PPI) targets. Many have assumed that a small molecule has little chance to satisfy and complement the huge and flat surface of a protein-protein interaction, which have surface areas of around 1600 Å2 and an average of 22 residues per binding partner (Gonzalez-Ruiz and Gohlke, 2006).

The experimental evidence of the existence of “hot spots” in the complementary surface of protein-protein complexes challenges these beliefs and opens the door for small molecules to modulate these interactions. It has been found that the stabilization energy of the multiprotein complex comes mainly from small areas of the interface between the proteins (Clackson and Wells, 1995). Therefore, small molecules may be able to recreate similar stabilization energy if they are able to interact with these “hot spot” regions in one of the partners of the complex. Again this relates to inhibitors having fragments of high ligand efficiency.

Small molecules modulating protein-protein interactions are now emerging not only from pharmaceutical companies but also from academic research (Arkin and Wells, 2004; Pagliaro et al., 2004; Whitty and Kumaravel, 2006). Examples include the inhibition of p53-MDM2 interaction (Murray and Gellman, 2007), antagonists of the Bcl-2 antiapoptotic family proteins (Papadopoulos, 2006), and the blockade of the binding of IL2 to its receptor IL-2Ra (Thanos, DeLano, and Wells, 2006).

Example: IL-2/IL-2Ra: In 1997, Hoffmann-la Roche scientists presented the first nonpeptide small-molecule inhibitor of a cytokine/cytokine receptor interaction (Tilley et al., 1997). IL-2/IL-2Ra is a system with low biological risk as a drug target, as antibodies for the alpha subunit of the IL-2 receptor were clinically effective as immunosuppressive agents. The design of small molecules substitutes for these antibodies, based on structural information of IL-2, enhanced by mutagenesis experiments to map the binding site of the IL-2Ra. Compounds synthesized to mimic IL-2 were indeed inhibitors of the cytokine/ cytokine receptor interaction. Surprisingly, NMR studies showed that the small molecules bind to IL-2 itself. Scientists at Sunesis then cocrystallized the IL-2/Roche inhibitor and applied their Tethering® technology (Erlanson et al., 2000) to characterize the IL-2 binding site and identify chemical fragment binders (Arkin et al., 2003). They found that the IL-2 interacting surface is highly adaptive, as there is a substantial difference between the apo and holo crystal complexes. This example highlights the importance of exploring flexibility in the interacting regions to identify possible adaptable hot spots that could create grooves for a small molecule to bind and disrupt protein-protein interactions (Thanos, DeLano, and Wells, 2006).

Protein-Protein Interaction Hot Spots. Systematic alanine mutation (alanine scanning) at protein-protein interfaces can be used to measure the contribution to the interaction energy of the residues side chains at the surface (Janin, 2000) to identify hot spots. But one should exercise caution when interpreting alanine scanning data. The change in energy can be due to factors other than the atomic interactions of the residue side chain, for example, changes in the conformation of the unbound and bound mutant (DeLano, 2002).

Starting with the structure of the protein-protein complex, three main computational approaches can be used to predict hot spots in PPI (Gonzalez-Ruiz and Gohlke, 2006). Computational alanine scanning performs energy calculations to estimate the difference in free energy between the wild-type complex and the complex with a single mutation to alanine in the interface. Mutations that lead to a significant change in the free energy of the complex are predicted to be at a hot spot. Energies are calculated using molecular mechanics coupled with solvation models and molecular dynamics (MD) to sample the conformational space of the complex (Massova and Kollman, 1999).

Alternatively, the difference in free energy between the wild-type complex and the alanine mutant is estimated with regression-based scoring functions, which are less computationally demanding. These functions are similar to those used for ligand-protein interactions (see scoring functions for docking in Chapter 27), where linear combination of terms including van der Waals, electrostatics and hydrogen bond interactions, water bridges, solvation, and molecular flexibility are optimized against experimental values of ΔΔG (Kortemme and Baker, 2002).

A third approach applies graph theory to protein-protein complex residues. It has been found that small-world networks describe the topology of the interfaces (Del Sol and O’Meara, 2005). These small-world networks are graphs where each node can be reached with small number of edges due to the existence of highly central node or hub (by analogy, on average everyone in the world has 6° of separation to everyone else via highly popular people). Furthermore, these central nodes correlate with experimentally determined hot spots.

Protein-Protein Interaction Flexibility. From the viewpoint of developing PPIs as drugs, predicting protein flexibility has two main applications: site adaptability and allosterism. Appropriate ligand binding pockets may be “preformed” at the interaction surface (e.g., MDM2), however they may form in response to protein modification, or be induced to form by a ligand (e.g., in the case of IL-2). Prediction of site adaptability would be invaluable for ligand design. In fact, the assessment of target druggability can change dramatically if one takes into account protein flexibility. Brown and Hajduk have shown recently how their druggability index (Hajduk, Huth, and Fesik, 2005a; Hajduk, Huth, and Tse, 2005b) varies when molecular dynamics simulations (Chapter 37) are included in the prediction (Brown and Hajduk, 2006). Of course, one way to bypass the inherent chemical risk in modulating protein-protein interactions is by finding allosteric inhibitors that indirectly affect the association.

Although binding site flexibility has a very important role in molecular recognition, it is still very challenging to predict. However, there is already an arsenal of structural bioinformatics tools, which can sample molecular conformational space. They can be divided into three main techniques: molecular dynamics, normal mode analysis, and constrained geometric simulation (Gonzalez-Ruiz and Gohlke, 2006). Molecular dynamics generates conformational pathways between states. This approach uses an all-atom model and therefore is computationally expensive; Gromacs (van der Spoel et al., 2005) is a commonly used software for these simulations.

The second technique to sample flexibility is through normal mode analysis (NMA— Chapter 37). Structural perturbations around a local minimum are explored by calculating vibrational modes of the system. In recent years, elastic network models are being widely used. In these models atoms are considered as network nodes connected by harmonic springs (Liu and Karimi, 2007). The third computational technique uses graph theory flexibility concepts for an efficient sampling of the protein mobility. constrained geometric simulation (CGS) considers atoms as nodes and edges as distance constraints defined by the covalent and hydrogen bonds between atoms. Rigid and flexible regions are determined by the geometric constraints that these edges impose on the nodes (Jacobs et al., 2001).

Chemical Genetics

The term “chemical genetics” describes the analysis of phenotypic function by the use of chemical probes. To dissect the function of a specific protein, a tool compound or probe should be a selective inhibitor (or activator) of this protein above all others within the cell. Compounds with this characteristic are rare or possibly even nonexistent. To overcome this difficulty, Shokat and coworkers (Knight and Shokat, 2007) have used a technique, sometimes termed orthogonal chemical genetics (Belshaw et al., 1995; Smukste and Stockwell, 2005), whereby a protein is altered in such a way as to create a unique binding site. At the same time a compound that will fit that pocket and only that pocket is designed and synthesized.

Cells are then engineered to express the mutant protein in place of the naturally occurring version. The cognate-designed compound can then be used to selectively inhibit that protein. Cell-based assays can be carried out in the presence of the inhibitor to understand the function of the protein. Several protein and lipid kinases have been examined in this way, including cdc28, HER3, and PI3Kα (Knight and Shokat, 2007 and references therein).

In each case, the “gatekeeper” residue was mutated to a small residue such as glycine to open up the “gatekeeper” pocket. This pocket, in conjunction with other specific interactions elsewhere in the ATP binding site, is used to provide the unique pocket required for this technique to be successful. In the example of p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (RSK), Cohen et al. (2005) targeted the naturally open gatekeeper pocket (gatekeeper = threonine) and a second selectivity providing interaction of a covalent attachment to a proximal noncon-served cysteine. This combination of two selectivity features is only found in RSK1, RSK2, and RSK4, which in turn allowed the authors to selectively target this family. Then they engineered in this cysteine other protein kinases containing the open gatekeeper pocket and used their RSK inhibitor to selectively knockdown their activity.

This approach has the advantage over gene knockout or catalytically dead knock-in approaches to functional characterization in that the protein is disabled reversibly and on a timescale that can be physiologically and medicinally relevant. Gene knockouts also have the added disadvantages of often causing developmental problems, compensatory proteins to be upregulated, and a loss of normal protein-protein interactions.

HIT IDENTIFICATION

Once one has identified a target binding site and structural information is available, structure-based virtual screening (SBVS—Chapter 27) can be employed to identify chemical starting points for a drug lead identification program. Such techniques are now used routinely for the identification of focused screening sets from either commercial supplier’s catalogs or internal compound collections (Oprea and Matter, 2004; Davis et al., 2005). These sets are tested experimentally to identify hit molecules that can form the starting points for a medicinal chemistry lead identification program.

Various VS techniques can be employed to this end and it is sensible to use all the information available about a target, drawing on the full range of structural bioinformatics techniques. Structure-based methodologies have the advantage over some ligand-based methods in that they do not explicitly bias the compound selection toward any particular chemotype, and therefore they can be a good way of identifying novel chemical matter (Kitchen et al., 2004).

The target information gathering process can be extended to include proteins in the same family or those that have a similar binding site to the target. The selection of libraries that are focused on whole gene families, for example, protein kinases or ATPases in general, can be aided by the use of structural information (Bohm and Stahl, 2000). As with ligand-based virtual screening, SBVS need not be limited to available compounds or even to compounds that have ever been made. Virtual compounds can be fragments of real compounds or whole imaginary compounds. The search for hits can therefore extend further into unexplored areas of “chemical space” (Weininger, 1998; Fink and Reymond, 2007).

While the use of protein structures has the potential to greatly aid the hit finding process, in order for the full potential to be realized, a number of factors have to be considered. First, the nature of the protein structure itself. For instance, is it a crystal structure or an NMR structure? What is the quality and resolution of the structure? What is known about the binding site location and protein flexibility? Is it an apostructure or does it have an inhibitor or natural ligand in the binding site? Are the locations of hydration sites known?

Software applications need to assess the electronic and shape complementarities of flexible ligands for flexible proteins and to do this quickly enough to allow searching of large collections of compounds in a timely manner.

Measures of Virtual Screening Success

It is important to try and understand the ability of the available programs to make useful predictions concerning molecular recognition as they can be very expensive and time consuming. The extent of the predictive power is never known with any precision because truly objective tests of such software are rare and performance varies not only between operators but also between protein families. Prospective users perform in-house validation of software using proprietary data sets to gain an understanding of performance and relevance in their working environments.

The success of VS is usually measured by the number of real hits identified, compared to the number expected to be achieved by random selection of compounds for testing (the “enrichment”). Some researchers quote the area under the curve of the “receiver-operating characteristic” (ROC) plot, while others use the enrichment rate (the hit rate/the random hit rate) for the initial selections (Chapter 27). The random hit rate is simply estimated by multiplying the number of compounds selected by the proportion of true hits with the entire pool of compounds. Assessment of virtual screening methodologies is usually done in hindsight. Of course, this is far from ideal and truly blind predictions like those used in the CASP (Moult et al., 2005) and CAPRI (Méndez et al., 2005) (Chapter 28) competitions would be preferable. McMaster University did hold a blind high-throughput virtual screening competition using Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) as a test case. Unfortunately, no competitive inhibitors were identified in the real HTS and therefore the study was not a good assessment of the techniques used (Lang et al., 2005). Interestingly, 50% of the 32 competitors used only ligand-based methods, 10% only used protein structure-based methods, and the remaining 40% used a combination. A comparison of the enrichment achieved by a variety of methods applied to the same data sets have been shown to be useful (e.g., Nettles et al., 2006; Hawkins, Skillman, and Nicholls, 2007). In this way, the timings and ease of use can also be compared, but again, bias is difficult to avoid.

Protein Structure in Hit Identification

Nearly all SBVS is done using X-ray crystal structures rather than NMR structures. The former are more readily available in the public domain (the ratio of X-ray to NMR structure in the pdb is approximately 6 : 1) and more commonly produced within pharmaceutical companies, but the latter may have advantages when considering an ensemble of structures to take protein flexibility into account. See Chapters 4 and 5 for more information on the complementarity of NMR and X-ray structure determination.

The resolution of a crystal structure is more critical for some SBVS techniques than others. For instance, docking can be highly dependent on the atomic coordinates and very small differences can result in a completely different binding mode. For structures with a resolution above 3.5 Å, it may be advisable to use a virtual screening method other than high-throughput docking. High-resolution structures have the advantage of revealing the sites of ordered water molecules. Water molecules that form three or more hydrogen bonds to the protein are considered to be integral parts of the protein structure (the so-called structural waters).

The inclusion of such water molecules can be very important to achieve the correct binding mode with docking (e.g., Pickett et al., 2003). However, even if absent from a crystal structure, these structural waters can be predicted with good accuracy (Pitt, Murray-Rust, and Goodfellow, 1993; Verdonk et al., 2001; Verdonk et al., 2005). Water molecules with two or less hydrogen bonds to the protein can sometimes be displaced by a ligand with the advantage of increasing water molecule disorder. If the hydrogen bonds are replaced with those to the ligand, compounds with increased potency and selectivity can result. Displacing water molecules from hydrophobic surfaces can often result in an affinity gain for a small molecule due to the hydrophobic effect, but these waters are usually too disordered to be observed in an X-ray crystal structure, except perhaps when they are confined to a small cavity (Garcia-Sosa, Mancera, and Dean, 2003).

Having a ligand in the crystal structure of the targeted binding site is extremely useful because it provides information on a successful set of binding interactions and a ligand conformation. In many cases, the structures of apoproteins are more open and disordered than respective ligand-bound structures. In other cases, allosteric pockets can open up only in the presence of a small molecule. Information on such binding sites is highly valued because they can provide a competitive advantage to a pharmaceutical company.

Binding of a ligand causes a conformational change in the protein to maximize complementarity. Crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes can therefore provide a negative image of the ligand that results in SBVS hits that are biased toward similar molecules. It can therefore be an advantage to use ligand-protein crystal structures generated with a diverse set of compounds.

Protein Modeling

It is often the case that a crystal structure of the exact protein one targeting is yet to be solved, but a structure of a homologous protein has been. If the homology is high or there are many related structures, useful models can be produced (Chapter 30) and even used for docking (Hillisch, Pineda, andHilgenfeld, 2004). It is highly advisable, if docking is to be attempted, to create a model with a tightly binding and preferably rigid compound in the binding site. This is possible in the comparative modeling package Modeller (Marti-Renom et al., 2000 and Chapter 30). Protein-ligand complex model construction has the same effect as cocrystallization in producing a negative image of the compound, and thus can help to find compounds with similar shape and hydrogen bonding functionality as the modeled compound. Another case where docking into homology models is productive is if there is a metal binding site or similar conserved interaction for which constraints can be used to anchor a compound in the binding site and thus remove three degrees of freedom. On the whole, when working with more speculative protein models and very low resolution or partially disordered crystal structures, a ligand-based virtual screen (LBVS) technique such as pharmacophore searching can be more appropriate than docking.

Structural Bioinformatics in Target Families

Almost any potential target will have related host proteins whose function must not be affected by a successful therapeutic. This will be true, for example, if one wishes to inhibit a protein from one of the larger gene families. In considering selectivity issues, certainly one must first look at related sequences in the same protein family. However, there is not necessarily a direct correlation between the similarities one would infer from homology and those one would infer from compound action. This is because only a small fraction of the residues in a protein interact directly with any one ligand. Although long-range interactions and conformational changes can play a role in inhibitor binding, in general it is those residues lining a ligand binding site that are of most importance.

The ATP cleft of the protein kinases serves as a good example. Although all protein kinases bind ATP in the same region and conformation, only a few of the residues facing the cleft are highly conserved. The remaining residues are subject to random drift, and thus distantly related kinases can actually end up having clefts more similar than more closely related kinases.

This use of noncontiguous regions of sequences to establish relationships was first introduced by Sandberg et al. (1998) and has more recently been described as structure-activity relationships and homology (SARAH) (Frye, 1999; Schäfer and Egner, 2007). In SARAH, protein targets are grouped both by their sequence similarities and by their ability to bind an array of compounds, such as may be determined from pharmaceutical HTS. SARAH builds on earlier ideas around affinity fingerprinting (Kauvar et al., 1995). As Frye points out, protein targets were often grouped according to their response to ligands before we had sequence information at our disposal (Lefkowitz, Hoffman, and Taylor, 1990).

Although conceptually very attractive, it has proven difficult to correlate the similarity of binding sites of protein kinases with the ligand they have been shown to bind, demonstrating the importance of long-range interactions and subtle complex conformational changes (Scapin, 2006a; Scapin, 2006b; Fedorov et al., 2007; Verkhivker, 2007).

Docking and Scoring

Programs such as GOLD (Jones et al., 1997; Verdonk et al., 2005) and FlexX (Kramer, Rarey, and Lengauer, 1999) are very good at predicting the binding mode of compounds removed from a crystal structure and after alternate conformations have been generated. However, because the changes to the shape of binding sites are often induced by compounds (as mentioned above), docking diverse compounds into protein structures is relatively unreliable. Some docking programs, such as Flo + (McMartin and Bohacek, 1997), FlexE (Claussen et al., 2001), and Glide (Friesner et al., 2004; Halgren et al., 2004) can take protein binding site flexibility into account and can often successfully predict a binding mode, even when a conformational change in the protein is required. When used for SBVS, docking is performed in a high-throughput mode (HTD). This can mean that factors such as protein flexibility have to be ignored to speed up the calculation.

Once docking is completed, ranking of potential binders is performed. A scoring function can be used to rank docked compounds by how well they fit into the binding sites. The development of these scoring functions is still a challenging area of research. The best that high-throughput compound ranking functions can currently hope to achieve is to filter out the nonsense results allowing a knowledgeable human to select from the remaining compounds visually. See Chapter 27 for more information on docking and scoring.

It has been argued that achieving the correct binding mode is not essential for VS, and that the most important measure of success is the number of hits identified. It is highly possible that HTD can achieve good enrichment rates purely by filtering out compounds that are too big to fit into the active site or too small to be detected by a biochemical assay. However, this type of enrichment could be achieved by simply filtering by molecular weight. Correctly identifying hits using HTD could be achieved by using the negative image effect mentioned above even if these hits do not bind in the same way as the query molecule removed from the protein-ligand complex crystal structure or homology model. However, it is possible that enrichment rates achieved this way might be attained much more efficiently than using a ligand-based similarity search program. In order for the HTD to make more use of the binding site structure, predicting the correct binding mode is essential.

Fragment-based approaches are proving to be effective in producing hit molecules (Hajduk and Greer, 2007). Fragments are typically molecules below a molecular weight of 250 Da that bind with micromolar to millimolar affinity and need to be extended in size to be turned into a “hit.” Relatively simple structures are more likely to bind to a given protein binding site and therefore hit rates are typically higher (Hopkins, Mason, and Overington, 2006) However, the relatively few interactions they make with the protein can make measuring binding affinity more difficult (Hann, Leach, and Harper, 2001) as well as docking and scoring more problematic. Although fragment screening has recently received much attention, it should be pointed out that drug discoverers have for some time used small molecules, often endogenous ligands, as starting points for medicinal chemistry.

Docking can also be used simply as an alignment method for conformation and alignment 3D QSAR methods, such as CoMFA (Cramer, Patterson, and Bunce, 1988), which can then be used to find new hits. This has the advantage of placing the QSAR model in the context of the receptor, thus facilitating interpretation. However, small variations in binding mode of conserved substructures, although likely to occur in reality, generate noise for CoMFA models and ligand-based overlays can achieve more predictive results (Cramer and Wendt, 2007).

Example: Protein Kinases. A realistic example of the virtual screening of a commercial compound collection is quoted in Kubinyi (2006): Forino et al. (2005) chose to search a commercial vendor’s catalog of 50,000 compounds using FlexX with a crystal structure of protein kinase B alpha (PKBα/Akt1). Compounds were selected for testing using a consensus scoring scheme followed by visual inspection. They identified 3 hits with low micromolar affinity after testing 100 compounds. This represents a hit rate of 3% and an enrichment over random selection of 15 (maximum enrichment possible 500). Further examples can be seen in Dubinina et al. (2007).

Pharmacophores

Structure-based pharmacophore (SBP) VS is an extension of methods originally developed for ligand-based compound selection. In its simplest form, it uses the active site volume as a means to limit the size of the resulting virtual hits. An added benefit is that the conformational space of flexible compounds is restricted, thus resulting in a more realistic fit to a pharmacophore. When using a homology model or low-resolution experimental structure, this method works well, as the size of the pocket can be expanded in areas of uncertain protein structure giving a larger margin for error. This approach is implemented very efficiently by the use of the so-called receptor exclusion spheres in the program Catalyst (Greene et al., 1994; Greenidge et al., 1998). Good results can be achieved by generating a 3D query from pharmacophoric features and receptor exclusion spheres, derived from a crystal structure of a protein-ligand complex. Receptor exclusion spheres and similar approaches in the programs Unity (Tripos, United States) and MOE (CCG Inc., Canada) do not serve to positively select compounds that fit the shape of the active site but complementarity can be used to help rank the resulting virtual hits. The Rocs program (Rush et al., 2005) does allow for a search of compounds that fit the shape of a binding site, but does not match predefined pharmacophoric features.

Neither SBP nor HTD approaches need small molecule starting points before they can be employed. Pharmacophores are generated based purely on the character of the binding site. This is an advantage, but it also presents a new problem as to how to choose the features that are essential for binding. The classic program GRID (Goodford, 1985) and knowledge-based system SuperStar (Verdonk et al., 2001) calculate “site points,” which are the positions of optimum interactions for chemical groups of different types. These points can be converted into pharmacophoric features, but typically there are too many points and choices must be made on which to be included in a pharmacophore. At least one method has been developed to automate this process (Chen and Lai, 2006).

An alternative approach is to use an exhaustive ensemble of pharmacophores. The program FLAP (Baroni et al., 2007) generates a fingerprint from all possible combinations of four-point pharmacophores. Once the generation of pharmacophores is automated, one can produce pharmacophores for whole families of proteins with the aim of producing an activity profile (Steindl et al., 2007) or selecting gene family focused library.

Using pharmacophore points to aid docking (e.g., FlexPharm from BioSolveIT, Germany) or to filtering docking results (e.g., Silver from CCDC, United Kingdom) is a good way of combining the two techniques. One can also use a pharmacophore search as a filter from which to go on and do a more CPU-intensive docking study.

Example: Protein Kinases. Again taken from Kubinyi (2006), Singh et al. (2003) of Biogen Inc. constructed a pharmacophore based on a crystal structure of SB 203580 (a well-known p38 inhibitor) bound to type I TGFbeta receptor kinase, using the program Catalyst. They did not use receptor exclusion spheres but the query compound to define the shape of the active site. Out of 200,000 commercial compounds, 87 fitted their pharmacophore. They do not quote a hit rate, but simply focus on one novel 5 nM hit. It subsequently turned out that Eli Lilly and Co. had independently discovered the same compound using a high-throughput cellular assay (Sawyer et al., 2003).

De Novo Design

In addition to the virtually screening preconstructed virtual compound libraries, construct ligands can be designed to fit a binding site from scratch (Schneider and Fechner, 2005). In theory, this is a far more efficient way to search chemical space, especially if a fragment growth strategy is employed. However, it is difficult for the developers of these methods to get the balance right between producing molecules that are so simple that they are uninteresting and those that are so complicated that synthesizing them would be unrealistic. Also, the algorithms are in competition with the inventiveness of the human mind, which can make leaps across huge distances in chemical space with confidence. Perhaps the greatest difficultly (as with docking) is that de novo design scoring functions cannot predict activity with any accuracy. In addition, a chemist has to undertake a costly custom synthesis based on an unreliable prediction. This can be a far higher hurdle to leap than simply purchasing an available compound. Even the availability of a low potency, but small fragment hit, can give the necessary confidence to pursue difficult synthetic chemistry approaches.

Combining Virtual Screening Methods

It has already been mentioned that docking and structure-based pharmacophores are increasingly mixed to produce hybrid methods. If small-molecule binders and the structure of the target are known, then SBVS techniques can be combined with ligand-based techniques (e.g., Taylor et al., 2007). If different approaches are used, then a consensus approach gives confidence in the results. In addition, different techniques will undoubtedly find different hits and therefore provide a greater range of starting points for a medicinal chemistry program. Once hit molecules have been identified, the next task is to structurally alter them with the aim of converting them into a drug leads.

A lead molecule for a drug discovery project can be defined as one having low nanomolar potency against its target, showing in vivo efficacy and having some selectivity over undesirable proteins. For more than 30 years, structure-based drug design has been used to speed up the process of optimizing small molecules to this end (Congreave, Murray, and Blundell, 2005). The fundamental impact of having protein structural information is in allowing medicinal chemists to select their next molecule to synthesize based on a clear visualization of the molecular recognition event. By bridging and building on resources in bioinformatics, structural biology, and structure-based drug design, structural bioinformatics can accelerate the quest for a potential drug by helping to provide guide design and medicinal chemistry. The next sections provide an introduction of each of the main components of structure-based design to convert a hit molecule into a lead.

Improving Ligand Affinity and Selectivity

The approach of optimizing potency and selectivity against a protein target using iterative steps of crystal structure analysis, compound design, synthesis, and testing is commonplace. Of the utmost importance is the introduction and retention of drug-like properties, while improving the activity profile. Another concept that has been taken up by medicinal chemistry teams is that of ligand efficiency (Hopkins, Groom, and Alex, 2004 Abad-Zapatero and Metza, 2005). Here, the affinity of the compound is compared to its molecular weight or other properties the medicinal chemists are seeking to optimize, such as lipophilicity, with the aim of generating potent molecules of minimum size.

It has been recognized that larger, more lipophilic molecules are relatively rare among drugs (Wenlock et al., 2003) and harder to optimize (Davis et al., 2005). However, the minimum size and lipophilicity of a lead will not only depend on the quality of the initial hit molecule from which it was derived, but also on the properties of the binding site targeted. For example, it has been found that synthetic ligands for some targets, such as peptide GPCRs, tend to be much larger and lipophilic than others, for example, ion channels (Paolini et al., 2006). In contrast, the adenine binding site of protein kinase ATP binding pockets, at least in the active ligand-bound conformation, is narrow and hydrophobic and consequent inhibitors tend to contain a key flat aromatic heterocyclic ring that results in poor aqueous solubility.

In addition to drug-like physical properties, the ever-present concerns of synthetic accessibility and novelty mean that SBDD is about more than simply improving the fit of a small-molecule hit for its target active site. That said, the use of structural information can be invaluable in revealing areas where physical properties can be improved without affecting potency or, much better still, while improving potency. Solubilizing groups are often added to the aromatic core of protein kinase inhibitors so that they extend out of the pocket and into the surrounding solvent or occupy the ribose or phosphate binding sites, which are more hydrophilic in character than the adenine binding site.

Many of the techniques used for hit identification (described above), such as docking, SBP, and de novo design, can also be applied to optimize the potency of these hits. For instance, small, focused virtual libraries can be designed around a single molecule to expand SAR. Docking or pharmacophore analysis can then be used to help prioritize synthesis. Similarly, de novo design software can be used to replace or extend a particular substituent of a hit molecule. In addition, because of the smaller number of molecules being considered at this stage, more computationally intensive techniques can be employed, such as flexible protein docking and molecular mechanics techniques such as energy minimization, molecular dynamics, and Monte Carlo (MC).

As already stated, the computationally efficient scoring functions used for virtual screening are unable to predict activities in a reliable way. A number of methods that are more computationally intensive but also more theoretically rigorous have been developed to try and predict binding affinity or relative activity from a structure of a ligand-protein complex. Free energy perturbation (FEP) is perhaps the most well known of this class of techniques and, in theory, can be used to calculate the difference in binding affinity of two closely related compounds (Gohlke and Klebe, 2002). The ability to do this would obviously allow medicinal chemists to have an accurate estimate of the activity of the next compound they planned to make based on the measured activity of its parent molecule.

Unfortunately, this scenario is far from becoming a reality, with practical considerations of the calculation preventing it thus far. These include difficulties in setting up the system, the length of time the calculations take to run, and the assumptions inherent in the system setup. Progress is being made toward ameliorating the two former problems, but the latter issue may well be system and compound dependent, and therefore will always lead to uncertainty. Examples of this type of consideration are the inclusion of explicit solvent in the calculation, changes in protonation state, and the large-scale or high-energy molecular motions.

Example: Protein Kinases and Free Energy Perturbation. Pearlman and Charifson (2001) applied the related technique, thermodynamic integration (TI) to a set of p38 MAP kinase inhibitors and obtained a very good correlation between calculated binding energies and measured IC50s for 12 of their 16 molecule set, although the range of activities was only slightly over 1 order of magnitude. These authors created the predictive index (PI) to aid comparison of binding energy calculations (+ 1 for perfect, 0 for random, and — 1 for a perfectly incorrect prediction). Their p38 test set achieved a PI of0.843. Michel, Verdonk, and Essex (2006) describe the application of FEP to CDK2 and other drug targets. Although they did not obtain useful predictions for their CDK inhibitors (PI < = 0.36), they did achieve high PIs for sets of neuraminidase (PI < =0.95) and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors (PI = 0.96). The authors also offer the opinion that it is now feasible to study 24 compounds a day using FEP on a 150 CPU cluster.

Example: Protein Kinases and Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area Method. Another technique that has recently been explored is the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) method (Kollman et al., 2000; Foloppe and Hubbard, 2006). Unlike FEP, this method is designed to cope with more diverse chemical structures. When Pearlman (2005) applied MM-PBSA to the p38 set used for the TI experiment (see above), the results were inferior (—0.04 ≥ PI ≤ 0.45). Kuhn et al. (2005) also applied MM-PBSA to the Pearlman and Charifson (2001) p38 data set and also to another diverse set of 12 p38 inhibitors. Results for the first set were on a par with those produced by Pearlman (—0.22 ≥ PI ≤ 0.31) and the second set produced even less predictive results.

The authors then went on to test whether MM-PBSA scoring could produce good enrichment in docking-based virtual screening. The results they obtained for their p38 test set were only slightly better than random but better than the conventional scoring method that they used (ChemScore). In contrast, all methods applied to their estrogen receptor test set produced good enrichments. In the case of COX-2, MM-PBSA did produce a reasonable enrichment over random selection while ChemScore did not. The authors state that MM-PBSA can produce results quickly (~15 min/compound on a single processor) and imply that the technique may have utility in the hit identification stage of a drug discovery project but not in lead optimization.

As can be surmised from the discussion above, predicting ligand affinity in the hit to lead phase of a project is at best difficult, even when good structural information is available.

Once at least one series of molecules has been created, the process of fine-tuning them in such a way that at least one example is fit enough to be tested in humans begins.

LEAD OPTIMIZATION

Potency and simple property filters, such as the rule-of-five, are often the main criteria in the lead discovery stage of a drug. To design a candidate medicine from the initial lead, however, one needs to consider a host of additional parameters that can affect the biopharmaceutical and safety properties of the drug such as the in vivo absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicology (ADMET). Tools of structural bioinformatics, namely, sequence-structure relationships and protein homology modeling, can be usefully employed in the field of ADMET modeling.

The most developed work in this field, relevant to structural bioinformatics, is in the area of cytochrome P450 modeling for the prediction of drug metabolism (de Groot, 2006). More than 90% of the drugs currently used are metabolized by only 7 of the 57 known human P450 isoforms. Iterative docking and refinement of structures and models has led to a structural rationalization of the metabolic sites of known drugs (Marechal and Sutcliffe, 2006) and these insights are used to generate pharmacophores and other in silico models predictive of P450 metabolism or inhibition. More recently, structures of some of the cytochrome P450 enzymes have been determined, allowing this to be integrated with previous predictive models for binding and metabolism (Williams et al., 2004; Yano et al., 2004).