36

METHODS TO CLASSIFY AND PREDICT THE STRUCTURE OF MEMBRANE PROTEINS

GLOSSARY

- Cell membrane: lipid bilayer common to all living cells that separates the cell from the external environment

- Cell wall: rigid layer external to the cell membrane that provides the cell with structural support, protection, and a filtering mechanism

- Outer membrane: the outside membrane (external to the cell membrane) of Gram-negative bacteria, choroplasts, and mytochondria

- Membrane core: very hydrophobic slab in the middle of the membrane made of the alkyl chain of phospholipids

- Membrane interfaces: polar areas that separate the membrane core from aqueous solutions and are made of phospholipid polar heads

- Membrane plane: any plane running parallel to the bilayer slab

- Membrane axis: any direction perpendicular to the membrane plane

- Membrane protein topology: number of transmembrane secondary structure elements (helices or strands) + location of the protein N-terminus at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane (“IN”) or at the opposite side (“OUT”)

- Positive-inside rule: basic residues Arg and Lys are about four times more frequent in cytosolic than in periplasmic loops

- Lily-pad effect: the stretch of hydrophobic amino acids interacting with the membrane core is flanked by aromatic belts made of Tyr and Trp

- Re-entrant loops: loops that penetrate the membrane but do not cross it

Membrane proteins represent about 20-30% of the expressed genes as predicted from the genome sequencing of bacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms (Jones, 1998; White and Wimley, 1998; Popot and Engelman, 1990). They are responsible for maintaining the homeostasis and responsiveness of cells by mediating a wide range of fundamental biological processes, such as cell signaling, transport of molecules impermeable to the membrane, intercellular communication, cell recognition, and cell adhesion. Understanding the structure and function of membrane proteins and studying their properties and biochemical mechanisms are therefore among the most important targets in biological and pharmaceutical research. The main difference between membrane and globular proteins is that they function in environments that have very different physicochemical properties. Processes involving membrane proteins happen within biological membranes, composed of phospholipid bilayers impermeable to polar molecules, whereas globular proteins function in aqueous media. Therefore, membrane proteins are highly insoluble and unstable in aqueous solutions leading to severe experimental problems associated with their study and the resulting amount of available structural data is scarce. Consequently, the membrane protein world is still less well known than the globular protein world despite its biological and physiological importance. (Jones, 1998).

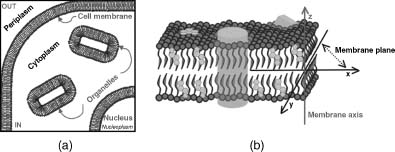

THE BIOLOGICAL MEMBRANE

Biological membranes serve as permeability barriers between cells, organelles, and their “external” environment (Figure 36.1a). These membranes are made of fluid phospholipidic bilayers that create a peculiar chemicophysical environment distinct from the surrounding aqueous solution and interact with many of the aforementioned membrane proteins (Figure 36.1). In three dimensions, a membrane bilayer can be described by a membrane plane and a membrane axis. The membrane plane is defined as the plane parallel to the bilayer slab (xy plane, according to the notation in Figure 36.1); the membrane axis is the perpendicular vector to the membrane plane (z-axis, according to the notation in Figure 36.1).

From a chemical point of view, biological membranes are mainly composed of glycerol-based phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). However, other lipids are pivotal and specific for different types of membranes. Sphingolipids, which are ceramide-based phospholipids and are slightly less apolar than glycerol-based lipids, and sterols, which are chemically unsaturated polycycles, are found in all eukaryotic membranes. In contrast, glycolipids with bulky sugar portions are found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and mitochondria. Glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids are made of a long and apolar tail, capable of hydrophobic interactions, and a polar phosphate group head, capable of hydrophilic interactions. These molecules are therefore flexible and amphipathic. Sterols are rather rigid compounds and are responsible for the increased rigidity of eukaryotic membranes—the higher fraction of sterols produces more rigid membranes and vice versa.

Figure 36.1. (a) Schematic representation of a section of a cell: IN, inside of the cell; OUT, outside of thecell. (b) Schematic representation of acellular membrane. Glycerophospholipids are shown in gray, sphingolipids in green, cholesterol in orange, and proteins in light blue. The membrane plane and the membrane axis are also shown with dark gray and red lines, respectively. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

Fluid lipid bilayers have a very high degree of intrinsic thermal disorder essential for accomplishing their biological function and therefore it is not possible to derive three-dimensional crystallographic images of their structure at atomic level. However, a high periodicity is present along the membrane axis and this allows the distribution of the principal chemical groups of lipids (such as methylenes, carbonyls, phosphates, and so on) along the axis to be calculated by diffraction studies (White and Wimley, 1998). The structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphocholine (DOPC) in Figure 36.2a shows that a phospholipid bilayeris a complex environment composed of nonpolar phases with different features. Infact, the bilayercan be intuitively divided into three parts: a central hydrocarbon core (red lines, 30 Å thick) and two interfaces (pink lines, 15 Å thick) that include most of the polar groups and play a pivotal role in membranes. These interfaces represent half of the membrane total thickness, undergo significant changes in polarity over very small distances, and are responsible for all polar and specific noncovalent interactions between the membrane and protein side chains.

Figure 36.2. (a) The structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphocoline (DOPC) calculated as the time-averaged spatial distributions of the chemical groups methyl (-CH3), carbonyl (-CH2-), -CH=CH-, and water projected onto an axis normal to the bilayer plane. The bilayer can be easily divided into three regions on the basis of the distribution of the water of hydration of phospolipid headgroups: a 30Å thick central hydrocarbon core (red vertical lines) including most of -CH2-, -CH3 and -CH=CH-,and twoside15Å interfaces (pink lines) including most of the polar group with their water of hydration. (b) The structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphocoline (DOPC) represented as the variation of charge density along the membrane axis. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

The biological membrane is therefore a very complex and dynamic environment where the protein function is driven by mechanisms specific and different from those observed in globular proteins in aqueous solutions such as in the cytosol and periplasm.

THE FOLDING PROCESS OF MEMBRANE PROTEINS

The folding of helical membrane proteins has been extensively studied and can be seen as a two-stage biological process, as proposed by Popot and Engelman in 1990 (Popot and Engelman, 1990). In a first step, transmembrane helices insert into the membrane and only afterward do they assemble to form the final tertiary or quaternary structure.

More recent studies have shown that helical membrane proteins follow a folding route parallel to secretory proteins (Figure 36.3. The very first hydrophobic segment translated by the ribosome, the transmembrane signal peptide, (Figure 36.3a), is recognized by the signal recognition particle (SRP), which docks to the ribosome and blocks the chain elongation process (Figure 36.3b). The new complex is then recognized by the SRP receptor (SR, Figure 36.3c), which targets it to the plasma membrane and makes it bind to the translocation machinery (Figure 36.3d). Subsequently, the SRP and SR separate from the complex, the elongation restarts, and the translocon releases the membrane protein inserting it directly in the membrane where it assumes its final fold (Figure 36.3e).

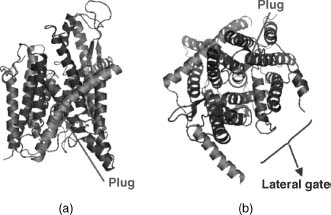

Translocons are known as Sec61complexes in eukaryotes and SecYin eubacteria and archaea complexes. A structure of the SecY/Sec61 translocon complex from Methano-coccus jannaschii is available at the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the code 1RHZ (Figure 36.4; Van Den Berg et al., 2004) and provides deeper insights on how the folding process occurs. During synthesis and integration of a nascent transmembrane protein, the translocon allows the nascent chain to pass through its pore, which is hourglass shaped and hydrophilic. Thus, it decides whether to move the sequence to the other side of the membrane (secretory proteins) or to release it into the hydrophobic core of the phospholipid bilayer by a lateral gate (integral membrane proteins). Finally, it deciphers the protein topology and decides if the protein needs to be flipped relatively to the membrane bilayer (Wallin et al., 1997; Seshadri et al., 1998). The release of the chain into the bilayer core is driven by a simple partitioning between the translocon and the membrane itself. Basically, the translocon and the membrane work cooperatively toward protein insertion, so that hydrophobic helices sufficiently prefer the bilayer while more polar helices are moved toward the aqueous compartment at the other end of the channel. However, the exact biological mechanism underlying the partitioning is still unknown (Von Heijne, 1986; Ulmschneider, Sansom, and Di Nola, 2005).

β-barrel membrane proteins have been shown to follow a very similar path. They are synthesized in the cytoplasm and targeted to the translocon, which releases them into the periplasm separating the outer membrane from the inner membrane. Subsequently, they are transported to the outer membrane by an unknown mechanism involving periplasmic chaperones (Bernstein, 2000; Ruiz, Kahne, and Silhavy, 2006).

Figure 36.3. Schematic diagram of the membrane protein synthesis and folding. (a) The ribosome synthesizes the first transmembrane segment (signal); (b) the signal is recognized by the signal recognition particle (SRP), which binds the ribosome blocking the chain elongation; (c) the SRP receptor (SR) recognizes the SRP complex and targets it to the membrane making it bind the translocation machinery; (d) SRP and SR are displaced and the chain elongation restarts; and (e) the membrane protein nascent chain is released and folds within the bilayer.

Figure 36.4. Structure of the SecY/Sec61 translocon complex from M. jannaschii as in the PDB (code 1RHZ). Left: side view. Right:top view. Subunits α, β, and γ arecolored in blue, green, and pink, respectively. The plug (transmembrane helix 2, subunit α, aa 59-64), which allows the insertion of the helix in the membrane, is colored in light blue. The figure was generated from the original PDB file using the software PyMol. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

WHY IS IT DIFFICULT TO SOLVE MEMBRANE PROTEIN 3D STRUCTURES?

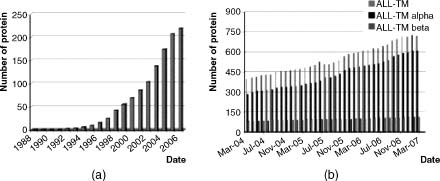

As mentioned in the introduction, membrane proteins constitute some of the most important targets in biological research and represent some of the most important drug targets for new pharmaceutical development. However, attempts to determine their 3D structures have been much less effective than the structure determination of globular proteins. Until recently, any structure-based drug design on membrane proteins had to rely on either homology modeling and/or site-directed mutagenesis studies. Although the big picture is improving, as shown in Figure 36.5, the PDB still includes tens of thousands of globular structures versus only hundreds of membrane protein structures. In July 2007, there were 775 membrane protein structures in the PDB, representing 125 different proteins. A similar gap can also be observed in the understanding of protein folding and assembly mechanisms—in vitro, in vivo, and computational studies have revealed much more information for globular rather than membrane proteins. The discrepancy can be easily explained considering that from an experimental point of view, membrane proteins are generally much more difficult to handle than their soluble counterparts. In fact, many studies fail at the first main task that is to obtain a sufficient amount of the required membrane protein.

Figure 36.5. Histogram of the variation of available 3D structures of membrane proteins over time. (a) Increase of membrane protein structures as in Stephen White’s Web resource from 1988 until now. (b) Increase of the total number of membrane protein structures in the past 3 years as in the PDB_TM database.

Structure determination of a protein involves three main experimental steps: expression, purification, and structure determination itself. Generally speaking, the isolation of membrane proteins is very difficult because of protein unfolding, instability, and aggregation, which occur very often (Booth and Curnow, 2006). There are several reasons for the poor success of such experiments. First of all, with only few exceptions, membrane proteins are poorly abundant in native tissues and therefore need to be expressed in heterologous systems. Moreover, they are more difficult to express as recombinant proteins because they have a complex folding mechanism, can cause toxic effects when inserted in host membranes, can be surrounded by a nonphysiological lipid environment due to the organism-specific membrane lipid composition, and experience nonnative posttranslational modifications typical of the host. For instance, a comparative analysis of overexpression yields for several G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in four main expression systems, Escherichia coli, yeast, insect, and mammalian cells, showed that in general GPCRs are only slightly overexpressed. Moreover, different GPCRs gave different expression levels in the same expression system and similarly the expression level of a given GPCR varied in different expression systems. Thus, predicting whether a membrane protein will be efficiently overexpressed in a given system is not a trivial task. On the other hand, and fairly obviously, the closer the host is to the native environment of the protein, the more likely it is to gain reasonable overexpression (Sarramegna et al., 2003). A further hurdle comes from the requirement of detergents during protein purification to improve protein solubility and prevent damage to the intrinsic transmembrane topology. In fact, detergents have a negative effect on the yield and stability of purified proteins and also reduce crystal contacts, hampering crystallization and structure determination.

Finally, although X-ray crystallography and NMR methods have improved significantly in the last years, available technologies are still more effective for water-soluble proteins. A key indicator of the extent of these problems is the lack of structure information available for the family of GPCRs, which represent over 50% of current drug targets (Lundstrom, 2006)— high-resolution structures have been determined for only one GPCR, bovine rhodopsin. Although many specific proteins have been studied individually in specific expression systems, leading to some remarkable successes (i.e., the rat neurotensin receptor in E. coli), overcoming all these experimental challenges for single protein often requires the engineering of multiple gene constructs with various deletions, fusion partners, and purifications, that is, it requires a considerable amount of time, effort, and funding (Grisshammer et al., 2005) and even then success is not always realized.

STRUCTURAL GENOMICS AND MEMBRANE PROTEINS

Structural genomics (see Chapter 29) pipelines have recently been established to improve the success rate of membrane protein structure determination. They require a broad area of expertise and a large handling capacity to allow the study of a large number of targets in parallel, thus providing a few advantages. First, as part of the systematic approach to expression, bioinformatics tools may reveal at an early stage which proteins represent better targets than others. Moreover, studies on a large number of targets in parallel can produce an adequate supply of protein to carry on purification and crystallization studies. Furthermore, large consortia of laboratories often have the capacity to handle alternative expression systems in parallel, improving the success of production of material suitable for further structural biology studies (Lundstrom, 2006). In the last few years, the efforts of 11 structural genomics networks focused on nonmembrane proteins have made a significant contribution to the increased coverage of globular protein superfamilies and folds (Todd et al., 2005). These networks target “novel” proteins, with the result that 67% of the protein domains they have determined are unique and lack a characterized close homologue in the PDB, while only 21% of domains from nonstructural genomics laboratories are unique. Consequently, this success has generated high expectations for the extension of such approaches to membrane proteins.

Current structural genomics initiatives that focus on membrane proteins focus either on whole genomes, on selected water-soluble and membrane protein targets, or exclusively on membrane proteins. The Centre for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics (CESG, http://www. uwstructuralgenomics.org/) deals with the whole Arabidopsis thaliana genome. The Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG, http://www.jcsg.org/) focuses on Thermotogota maritima proteome, mouse genome, and selected human GCPRs as specific membrane protein targets. The European Membrane Protein Consortium (E-MeP, http://www.e-mep.org/), funded by European Union, the privately funded Membrane Protein Network (MePNet, http://www.mepnet.org/), and the Membrane Protein Structure Initiative (MPSi, http://www.mpsi.ac.uk/), funded by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), are fully dedicated to membrane proteins and involve world leaders in membrane protein structural biology. Basically, all these projects aim at developing high-throughput methods for the expression, purification, crystallization, and structure determination of integral membrane proteins. In addition, MePNet specializes on GPCRs and MPSi on ion channels and transporters. The major challenge facing these membrane protein structural genomics initiatives is the production of sufficient protein in the form necessary for successful crystallization. Although it is now relatively straightforward to synthesize many different constructs, the number of possible constructs is very large and improved methods to define the lengths of loops and the topology are needed to help improve the design of successful constructs. Moreover, as these projects are beginning to determine novel membrane protein structures, such as the structures of divalent magnesium ion transporter CorA (PDB code 2BBJ) and of the open and closed forms of the spinach aquaporin SOP1P2;1 (PDB codes 2B5F and 1Z98, respectively), structural bioinformatics tools are needed to analyze and exploit this knowledge at the genome scale.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF MEMBRANE PROTEINS AND THE PREDICTION OF THEIR STRUCTURES

In this section, computational methods for the identification of membrane proteins and prediction of their structures will be presented. Many methods have been developed over the years for the prediction of membrane protein topology and structure. However, more effort has been invested in studying helical membrane proteins than their beta counterparts, because identifying long and very hydrophobic sequence stretches, such as transmembrane helices, represents an easier task than detecting the shorter and less hydrophobic strands.

Generally speaking, the effectiveness of prediction methods strongly depends on available information and knowledge. Therefore, an overview of the current knowledge about membrane protein structures will first be provided; then, the most well-known computational methods for the study of membrane proteins will be described. Finally, the main online resources fully dedicated to membrane proteins will be summarized.

What is Known About Membrane Protein Sequences and Structures?

Biological membranes provide a discontinuous environment, and therefore the amino acid composition of membrane proteins varies along the membrane axis. For both helical and β-barrel proteins, the stretch of hydrophobic amino acids interacting with the membrane core is flanked by aromatic belts made of Tyr and Trp that generate the so-called “lily-pad” effect (Wallin et al., 1997; Seshadri et al., 1998; Ulmschneider, Sansom, and Di Nola, 2005). In addition, for helical membrane proteins, the basic residues Arg and Lys are about four times more frequent in cytosolic than in periplasmic loops, whereas there is no comparable effect for negatively charged residues (the “positive-inside” rule) (Heijne, 1986). The GxxxG sequence motif, which is thought to facilitate close helix-helix interactions, and other periodic patterns have also been observed in transmembrane sequences with a frequency higher than random (Elofsson and Von Heijne, 2007).

The membrane asymmetry and discontinuity is also responsible for a key feature of membrane proteins, their topology. The topology of a membrane protein describes both the combination of the number of secondary structure elements, for example, the number of helices or strands that cross the membrane, and the location of the N-terminus of the first transmembrane secondary structure element. The cytoplasm side is designated as “in,” whereas the opposite side (periplasm, organelle media, etc.) is designated as “out.” It is worth noting here that in β-barrels the N-terminus has only been observed on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane (“in”).

In terms of 3D structure, due to constraints imposed by the membrane, integral membrane proteins show only two main architectures, β -barrels in the outer membrane and a-helix bundles in all cellular membranes. This is because structure and stability of membrane proteins depend on the thermodynamic cost of transferring proteins, which are very polar or even charged compounds, into the hydrophobic hydrocarbon core of the membrane. To lower this cost, polar backbone groups (—CO— and —NH—) must be shielded and are usually involved in hydrogen bonds, forming stable secondary structures, that is, either a-helices or β -strands.

Helical membrane protein structures can be made of long hydrophobic transmembrane helices (15-30 amino acids in length) lying at various tilt angles from the membrane axis; interfacial helices lying parallel to the membrane plane, re-entrant loops, which are loops that penetrate the membrane but do not cross it; and cytoplasmic or periplasmic globular domains. Moreover, helix kinks occur when prolines are found in the sequence.

β -barrel structures are made of an even number of shorter β -strands that lie in an antiparallel orientation and are usually connected by alternating long and short loops. Moreover, they show a typical dyad sequence repeat motif, that is, hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues alternate so that hydrophobic side chains point out toward the membrane and hydrophilic side chains point toward the inside of the protein (Wimley, 2003).

Identification of Membrane Proteins from Sequence

The identification of membrane protein from sequence first involves the detection of sequence fragments that are hydrophobic enough to be transmembrane, leading to a simple discrimination between membrane proteins and water-soluble proteins. However, membrane protein sequences contain more information than just the hydrophobicity and can be used to predict protein secondary structure and topology.

The earliest but still most widely used method to identify helical membrane proteins is the

sliding-window analysis of the hydrophobicity (H ) of protein sequences (Rose, 1978; Kyte and Doolittle, 1982), which is based on

the assumption that on average transmembrane helices are more hydrophobic than water-soluble regions.

The method consists of plotting the average hydrophobicity of a 19 residue segment of a protein sequence

against the “central” residue number, so that the most hydrophobic segments of a chain can be detected.

The segment length value was optimized by comparing the average hydropathy of a set of transmembrane

helices with a set of hydrophobic helices belonging to globular proteins (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982).

Obviously, the results of this H

) of protein sequences (Rose, 1978; Kyte and Doolittle, 1982), which is based on

the assumption that on average transmembrane helices are more hydrophobic than water-soluble regions.

The method consists of plotting the average hydrophobicity of a 19 residue segment of a protein sequence

against the “central” residue number, so that the most hydrophobic segments of a chain can be detected.

The segment length value was optimized by comparing the average hydropathy of a set of transmembrane

helices with a set of hydrophobic helices belonging to globular proteins (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982).

Obviously, the results of this H method

strongly depend on the hydropathy scales used (Jayasinghe, Hristova, and White, 2001). The most commonly

used scales include the Kyte and Doolittle (KD) scale (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982), based on water vapor

transfer free energies and interior-exterior distributions of amino acids; the Eisenberg Consensus (EC)

scale (Eisenberg et al., 1982), which is based on protein hydrophobic dipole; the semitheoretical

Goldman-Engelman-Steitz (GES) scale (Engelman, Steitz, and Goldman, 1986), which combines separate

experimental values for the polar and nonpolar characteristics of groups in the amino acid side chains;

and the White and Wimley (WW) scale (White and Wimley, 1999), composed of experimentally derived

transfer free energies between water and a phosphatidylcholine bilayer interface. The H

method

strongly depend on the hydropathy scales used (Jayasinghe, Hristova, and White, 2001). The most commonly

used scales include the Kyte and Doolittle (KD) scale (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982), based on water vapor

transfer free energies and interior-exterior distributions of amino acids; the Eisenberg Consensus (EC)

scale (Eisenberg et al., 1982), which is based on protein hydrophobic dipole; the semitheoretical

Goldman-Engelman-Steitz (GES) scale (Engelman, Steitz, and Goldman, 1986), which combines separate

experimental values for the polar and nonpolar characteristics of groups in the amino acid side chains;

and the White and Wimley (WW) scale (White and Wimley, 1999), composed of experimentally derived

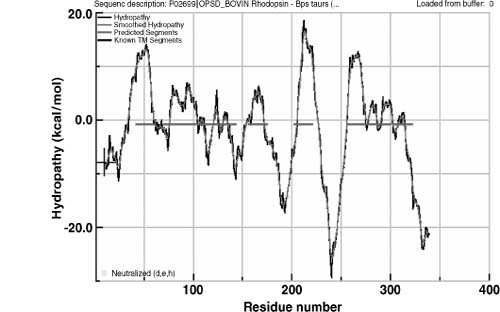

transfer free energies between water and a phosphatidylcholine bilayer interface. The H plot of bovine rhodopsin calculated using the WW scale

is shown in Figure 36.6.

plot of bovine rhodopsin calculated using the WW scale

is shown in Figure 36.6.

Figure 36.6. An example of hydropathy plot (Hf). The bovin rhosopin sequences analyzed using the WW scale within the Membrane Protein Explorer (MPEx) program (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/mpex /). Red lines represent the hydrophobicity threshold that defines protein segments as transmembrane or globular.

A significant amount of new information has become available since the development of the

H method. Experimental studies indicate the

presence of topogenic signals in helical integral membrane proteins, such as sequence patterns that

correlate with the topology of the membrane-spanning segments (see positive-inside rule and lily-pad

effect, described in Section “What is Known About Membrane Protein Sequences and Structures”). First and

early attempts to integrate topogenic rules into the heart of the secondary prediction process allowed

the development of automated methods for the prediction of transmembrane protein secondary structure and

topology (Claros and Von Heijne, 1994; Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1994). MEMSAT (Jones, Taylor, and

Thornton, 1994) was the first method to integrate the prediction of topology with the prediction of

transmembrane segments, but since then many other methods have been published, implementing more

sophisticated machine learning techniques such as neural networks and hidden-Markov-Models, such as

TMHMM (Sonnhammer, Von Heijne, and Krogh, 1998) and HMMTOP (Tusnady and Simon, 2001). A summary of the

most well-known methods available online is provided in Table 36.1. A typical machine learning method for the

prediction of membrane protein topology and transmembrane segments classifies each amino acid according

to four states, cytoplasmic (inside) loop, transmembrane, noncytoplasmic (outside) loop, and globular,

and is therefore able to assign transmembrane segments and the location of the N-terminus of the first

transmembrane helix. Benchmarking studies published in early 2000s showed that the most effective

methods for the prediction of transmembrane helices had accuracies in the 55-60% range for eukaryotic

proteins (Chen, Kernytsky, and Rost, 2002; Cuthbertson, Doyle, and Sansom, 2005). These results proved

that despite the number of new methods, there was remarkably little progress in terms of the prediction

accuracy and suggested that the limitation in prediction accuracy was not due to the algorithm being

employed but due to the lack of new biological information. In fact, prediction methods analyzed in the

studies rely only on two main basic features, the hydrophobicity of transmembrane helices and the

positive-inside rule.

method. Experimental studies indicate the

presence of topogenic signals in helical integral membrane proteins, such as sequence patterns that

correlate with the topology of the membrane-spanning segments (see positive-inside rule and lily-pad

effect, described in Section “What is Known About Membrane Protein Sequences and Structures”). First and

early attempts to integrate topogenic rules into the heart of the secondary prediction process allowed

the development of automated methods for the prediction of transmembrane protein secondary structure and

topology (Claros and Von Heijne, 1994; Jones, Taylor, and Thornton, 1994). MEMSAT (Jones, Taylor, and

Thornton, 1994) was the first method to integrate the prediction of topology with the prediction of

transmembrane segments, but since then many other methods have been published, implementing more

sophisticated machine learning techniques such as neural networks and hidden-Markov-Models, such as

TMHMM (Sonnhammer, Von Heijne, and Krogh, 1998) and HMMTOP (Tusnady and Simon, 2001). A summary of the

most well-known methods available online is provided in Table 36.1. A typical machine learning method for the

prediction of membrane protein topology and transmembrane segments classifies each amino acid according

to four states, cytoplasmic (inside) loop, transmembrane, noncytoplasmic (outside) loop, and globular,

and is therefore able to assign transmembrane segments and the location of the N-terminus of the first

transmembrane helix. Benchmarking studies published in early 2000s showed that the most effective

methods for the prediction of transmembrane helices had accuracies in the 55-60% range for eukaryotic

proteins (Chen, Kernytsky, and Rost, 2002; Cuthbertson, Doyle, and Sansom, 2005). These results proved

that despite the number of new methods, there was remarkably little progress in terms of the prediction

accuracy and suggested that the limitation in prediction accuracy was not due to the algorithm being

employed but due to the lack of new biological information. In fact, prediction methods analyzed in the

studies rely only on two main basic features, the hydrophobicity of transmembrane helices and the

positive-inside rule.

With the advent of the genomic era, large-scale computational analyses have been performed for membrane proteins (Lehnert et al., 2004) and a recent benchmarking study showed that methods that include evolutionary information, such as the newest versions of Phobius (Kall, Krogh, and Sonnhammer, 2007) and MEMSAT, are able to predict the correct topology for more than 70% of the membrane proteins in the benchmark set (Jones, 2007). Moreover, global experimental data of the topology of the E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae inner membrane proteomes have recently been published (Daley et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006). The inclusion of experimental information significantly improves the prediction of membrane protein topology, leading to correct assignments for about 80% of the proteins (Kim, Melen, and Von Heijne, 2003a; Bernsel and Von Heijne, 2005; Daley et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006).

The topology prediction for β-barrel proteins is more complicated. Although many structural “rules” are known, the discrimination of β-barrel membrane proteins from water-soluble proteins is more difficult because hydrophobic amino acids are hidden in the dyad repeat and there are fewer apolar amino acids in a β-strand than in an α-helix due to their intrinsic geometry (the average interresidue distance for α-helices and β-strands is 1.5 Å and 2.7 Å, respectively) (Wimley, 2003). The main methods for predicting the topology of β-barrel membrane proteins are listed in Table 36.1. A recent benchmarking evaluation (Bagos, Liakopoulos, and Hamodrakas, 2005) showed HMM-based methods, such as ProfTMB, to be the best available predictors, claiming accuracy higher than 80%.

TABLE 36.1. Available Resources for the Prediction of Membrane Protein Topology

| Resource | Web Site | Information Used for Prediction |

| TopPred2 (Claros and Von Heijne, 1994) | http://www.genomics.purdue.edu/Pise/5.a/toppred-simple.html | Hydrophobicity |

| MEMSAT3 (Jones, 2007) | http://www.psipred.net | aa statistical preferences and evolutionary information |

| TMAP (Cuthbertson, Doyle, and Sansom, 2005) | http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/tmap.html | aa statistical preferences and evolutionary information |

| PHDhtm (Rost, Yachdav, and Liu, 2004) | http://www.predictprotein.org | ANN and evolutionary information |

| TMpred (Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993) | http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html | aa statistical preferences |

| TMHMM/PHOBIUS (Krogh et al., 2001; Kall, Krogh, and Sonnhammer, 2007) | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/ | Various, HMM |

| HMMTOP (Tusnady and Simon, 2001) | http://www.enzim.hu/hmmtop/ | Various, HMM |

| OrientTM (Liakopoulos, Pasquier, and Hamodrakas, 2001) | http://athina.biol.uoa.gr/orienTM/ | Position-specific statistical information |

| SPLIT4 (Juretic, Zoranic, and Zucic, 2002) | http://split.pmfst.hr/split/4/ | aa statistical preferences |

| THUMBUP (Zhou and Zhou, 2003) | http://sparks.informatics.iupui.edu/Softwares-Services_files/thumbup.htm | aa mean burial propensities |

| PONGO (Amico et al., 2006) | http://pongo.biocomp.unibo.it/pongo/ | Metaserver |

| β-Barrel Membrane Proteins | ||

| PROFtmb (Bigelow and Rost, 2006) | http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu/services/proftmb/query.php | HMM |

| ConBBPRED (Bagos, Liakopoulos, and Hamodrakas, 2005) | http://biophysics.biol.uoa.gr/ConBBPRED | Metaserver |

| PRED-TMBB (Bagos et al., 2004b) | http://biophysics.biol.uoa.gr/PRED-TMBB/ | HMM |

| Both α-Helical and b-Barrel Membrane Proteins | ||

| MINNOU (Cao et al., 2006) | http://minnou.cchmc.org/ | Prediction-based structural profiles |

Finally, a few methods have been published aiming at the identification of all β-barrel membrane proteins in whole genomes from the analysis of sequence composition, secondary structure prediction, and architecture of known structures (Wimley, 2002; Liu et al., 2003; Bagos et al., 2004a; Bagos et al., 2004b; Berven et al., 2004; Gromiha, 2005; Park et al., 2005). Some of these methods are available as online resources (see Section “Web-Available Data Resources for Membrane Proteins” and Table 36.1).

Identification of Membrane Proteins Using 3D Structural Data

Despite the structural constraints imposed by the membrane, distinguishing membrane proteins from water-soluble proteins using their 3D structures can still be difficult, since they share more similarities than differences. The cores of both membrane and globular proteins show a comparable hydrophobicity and the surface of water-soluble proteins often includes hydrophobic atoms and can also exhibit hydrophobic patches if protein-protein interactions occur. Likewise, transmembrane protein segments that mutually interact or are involved in enzymatic activity or transport can contain polar residues. Moreover, in oligomers, the interfaces between multichain water-soluble complexes are mostly hydrophobic, while they are likely to be polar in transmembrane oligomers and this jeopardizes the analysis of single monomers extracted from oligomeric structures. Therefore, methods for the identification of membrane protein using structures, rather than relying only on 3D structural differences with water-soluble protein structures, exploit the detection of the optimal position of the protein relative to the membrane bilayer.

The position of a protein in a lipid bilayer can be defined by four simple parameters (see

Figure 36.7): (1) The location of the

center of mass of the protein along the membrane axis (d ), that is, the

distance of its projection on the bilayer axis from the center of the bilayer; (2) the angles of

rotation( ) and (3) tilt (τ) of the main

protein axis relative to the orientation of the membrane axis; and (4) the thickness of the portion of

the protein that spans and interact with the bilayer (D). To predict the

optimal location of a protein in the membrane, the energy for each position needs to be evaluated by a

specific function. Two automated algorithms are currently available to locate the position of the

protein structure relative to the membrane bilayer and to detect putative membrane protein structures.

They are implemented in the PDB_TM and OPM membrane protein databases (Tusnady, Dosztanyi, and Simon,

2004;Tusnady, Dosztanyi, and Simon, 2005; Lomize et al., 2006a; Lomize et al., 2006b). PDB_TM uses the

TMDET algorithm, which scans protein 3D coordinates, builds the possible biological complex, analyzes

the internal symmetry of the structure, calculates the membrane-exposed area, and searches for the best

membrane plane. Different positions of proteins in the membrane are evaluated by applying a specific

function, which depends on a hydrophobic factor, that is, the relative hydrophobic membrane-exposed

surface, and a structure factor mainly determined by the position of the protein axis relative to the

membrane axis. The protein is cut in 1 Å thick slices along the membrane axis, and the function is

calculated for each slice as the product of these two factors. If a 15 slice portion (corresponding to a

putative 15 Å membrane core) along a given membrane axis is found with a function value above a

predefined threshold, the axis is accepted as the best membrane axis for that protein and the structure

is classified as membrane protein. Otherwise, it is classified as globular protein. If there are many

orientations that score above the threshold, the highest scoring orientation is adopted.

) and (3) tilt (τ) of the main

protein axis relative to the orientation of the membrane axis; and (4) the thickness of the portion of

the protein that spans and interact with the bilayer (D). To predict the

optimal location of a protein in the membrane, the energy for each position needs to be evaluated by a

specific function. Two automated algorithms are currently available to locate the position of the

protein structure relative to the membrane bilayer and to detect putative membrane protein structures.

They are implemented in the PDB_TM and OPM membrane protein databases (Tusnady, Dosztanyi, and Simon,

2004;Tusnady, Dosztanyi, and Simon, 2005; Lomize et al., 2006a; Lomize et al., 2006b). PDB_TM uses the

TMDET algorithm, which scans protein 3D coordinates, builds the possible biological complex, analyzes

the internal symmetry of the structure, calculates the membrane-exposed area, and searches for the best

membrane plane. Different positions of proteins in the membrane are evaluated by applying a specific

function, which depends on a hydrophobic factor, that is, the relative hydrophobic membrane-exposed

surface, and a structure factor mainly determined by the position of the protein axis relative to the

membrane axis. The protein is cut in 1 Å thick slices along the membrane axis, and the function is

calculated for each slice as the product of these two factors. If a 15 slice portion (corresponding to a

putative 15 Å membrane core) along a given membrane axis is found with a function value above a

predefined threshold, the axis is accepted as the best membrane axis for that protein and the structure

is classified as membrane protein. Otherwise, it is classified as globular protein. If there are many

orientations that score above the threshold, the highest scoring orientation is adopted.

Figure 36.7.

Diagram of the parameters used to describe the position of a protein with respect to the membrane.

d distance of the protein center of mass (B) from the center of mass of

the bilayer (A);  : angle of rotation of

the protein axis relative to the orientation of the membrane axis; τ: angle of tilt of the protein

axis relative to the orientation of the membrane axis; and D: bilayer thickness.

: angle of rotation of

the protein axis relative to the orientation of the membrane axis; τ: angle of tilt of the protein

axis relative to the orientation of the membrane axis; and D: bilayer thickness.

The second approach (OPM) calculates the optimal spatial arrangement by minimizing the protein transfer energy from water to the membrane. The membrane is represented as a model in which the bilayer core is a planar hydrophobic slab of adjustable thickness and interfaces are defined by a polarity profile that takes into account the effective water concentration that varies gradually along the bilayer normally between the polar headgroups and the apolar core. The energy function is based on solvation parameters calculated from water-decadiene partition of uncharged amino acids and neglects electrostatic interactions and contributions of amino acids that are part of the protein surface but line hydrophilic pores and channels.

Identification of Structural Features from Sequence

As mentioned in Section “What is Known About Membrane Protein Sequences and Structures” several recently determined structures of helical membrane proteins showed that helix bundles, rather than being made simply of transmembrane helices perpendicularly penetrating the bilayer, also have irregular structural features, such as interfacial helices, reentrant loops, and proline-induced kinks. In addition, it is clear that the degree of amino acid exposure to lipid and residue distances from the middle of the membrane are very important for the interaction of proteins with the membrane and their function. Consequently, a new and more subtle definition of topology as a two-and-a-half dimension (2.5D) structure has been proposed by von Heijne and Eloffson (Elofsson and Von Heijne, 2007).

Methods to predict 2.5D structural features from sequence have been recently developed. TOP-MOD is a novel HMM-based predictor of re-entrant loops (Viklund, Granseth, and Elofsson, 2006). ZPRED is a method to predict the Z-coordinates of amino acids along the membrane axis, that is, their distance from the middle of the membrane, based on HMM and neural network techniques that also include evolutionary information (Granseth, Viklund, and Elofsson, 2006). The degree of lipid exposure for a residue can be predicted by LIPS, which is available as a Web server. It is based on a canonical model of coiled coil helices where the surface of each helix is partitioned into seven surface patches (faces) that can interact with lipids or other helices (Adamian and Liang, 2006). Finally, proline-induced helix kinks can be confidently predicted from the degree of conservation of proline in multiple alignments (Yohannan et al., 2004a; Yohannan et al., 2004b).

2.5D predictions obviously represent a useful step forward toward more reliable predictions of membrane protein 3D structures and will also be helpful in the process of structural classification to discriminate between protein families with the same overall topology.

Prediction of Membrane Protein 3D Structure

Compared to the prediction of the tertiary structure of water-soluble proteins, the prediction of the structure of membrane proteins is, in principle, an easier problem, since the constraint provided by the lipid bilayer to align transmembrane structure elements reduces the complexity of the problem. Despite this relative simplicity, little attention has been focused on the prediction of membrane protein structure. This neglect may reflect the limited variety of anticipated forms or more probably a lack of experimental data from which to derive rules to assess reliability.

As for the prediction of 3D structures of globular proteins, homology modeling, fold recognition, or de novo modeling methods should be used for membrane proteins as dictated by the available experimental information. These three techniques have been extensively described in Chapters 25-27. However, their application to membrane proteins needs particular care because of the physicochemical properties and constraints of the membrane.

None of the commonly used homology modeling programs has been explicitly modified for membrane proteins. However, the reliability of the application of standard homology modeling techniques, developed for globular proteins, to membrane proteins has recently been evaluated on a benchmark data set composed of homologous membrane protein structures (Forrest, Tang, and Honig, 2006). In particular, three issues have been addressed: the accuracy of amino acid substitution matrices used for the sequence alignment, the effectiveness of secondary structure prediction, and the relationship between sequence identity and structure similarity.

Results show that the construction of homology models of membrane proteins and globular proteins follows similar general rules and comparable trends are observed with respect to sequence-structure relationship (Chothia and Lesk, 1986; Flores et al., 1993) and alignment accuracy (Tang et al., 2003). Moreover, among the many modeling programs available, SegMOD/ENCAD (Levitt, 1992) and Modeller 7v7 (Sali and Blundell, 1993) have been showed to produce the highest quality models in terms of stereochemistry, whereas NEST (Petrey et al., 2003) provides models that are more similar to the target native structure. Among the existing loop prediction programs, PLOP (Xiang, Soto, and Honig, 2002; Jacobson et al., 2004) is reported as the most accurate, whereas Loopy (Xiang, Soto, and Honig, 2002) as the fastest (Punta et al., 2007).

The ab initio/de novo modeling of membrane proteins is unfortunately far more complicated. The ab initio modeling of β-barrel proteins has not been reported, whereas for helical proteins some progress has been achieved. In the ab initio prediction, a very important role is played by the prediction of the interactions between pairs of transmembrane helices, which lead to the final protein fold. Interhelical interactions are particularly difficult to identify since they occur within protein chains but also between different oligomers in multimers. Several interhelical interaction studies have been published (Senes, Gerstein, and Engelman, 2000; Fleishman and Ben-Tal, 2002; Degrado, Gratkowski, andLear, 2003; Liang et al., 2003), mostly aiming at the detection of key motifs that recur in transmembrane helix interfaces, although no Web servers for the prediction of these interactions are currently available.

Several methods for the de novo modeling of integral membrane proteins have been developed, although most of them have been tested on very few structures due to the paucity of the available experimental data. Known methods implement different approaches, such as potential smoothing and search algorithms (Pappu, Marshall, and Ponder, 1999), fragment-assembly approaches combined with knowledge-based potentials (Pellegrini-Calace, Carotti, and Jones, 2003; Hurwitz, Pellegrini-Calace, and Jones, 2006; Yarov-Yarovoy, Schonbrun, and Baker, 2006), and oligomer symmetry combined with Monte Carlo searches (Kim, Chamberlain, and Bowie, 2003b). However, they only work for proteins with less than 7 transmembrane helices and, to our knowledge, are not available as online tools. The only Web-based resource available is SWISS-MODEL 7TM (http://swissmodel.ncifcrf.gov/cgibin/sm-gpcr.cgi ) (Arnold et al., 2006), which lies on the boundary between homology modeling and de novo modeling. It was designed to extend the homology modeling of 7 transmembrane helical proteins by allowing the choice of “canonical” templates, that is, templates with clear sequence similarity with the protein target, and “computational” templates, which are group-specific templates (GSTs) generated from low-resolution structural data for a number of selected 7TM receptors for which sufficient relevant mutagenesis data are available.

WEB-AVAILABLE DATA RESOURCES FOR MEMBRANE PROTEINS

Currently there are several Web resources, as summarized in Table 36.2, which are dedicated to membrane proteins and include a significant amount of information, from sequence to 3D structures, crystallization details, and relationships with diseases.

Web Collections of Membrane Protein Structures

Five collections of membrane protein structures are available online. The Membrane Protein Data Bank (MPDB, http://www.mpdb.ul.ie/) (Raman, Cherezov, and Caffrey, 2006) is a relational database of structural and functional information on integral, anchored, and peripheral membrane proteins based on the PDB. Each MPDB entry includes protein name, size, function, and a number of features, such as the family designation according to the Transporter Classification (TC) system (see Section “Classification of Membrane Proteins”) (Saier, Tran, and Barabote, 2006), the family annotation as in PFAM, the secondary structure of the transmembrane domain, as observed in the crystal structure, and some experimental details.

The best known data bank “Membrane Proteins of Known 3D Structure” from Stephen White (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html) is the most comprehensive and provides useful information about integral membrane proteins, whose 3D structures have been determined to a resolution sufficient to identify transmembrane helices of helix-bundle membrane proteins (4-4.5 Å). In its July 2007 writing, it includes 259 entries of which 125 are “unique” structures that are taken as the representative of the set of proteins of the same “type” but from different species. The “Membrane Proteins of Known Structure” (http://www.mpibp-frankfurt.mpg.de/michel/public/memprotstruct.html) from Hartmut Michel is a list of membrane proteins with known structure and also includes crystallization conditions and key references for structure determination. However, at the time of writing, the resource has not been updated for more than one year. The recent PDB_TM (http://pdbtm.enzim.hu/) (Tusnady, Dosztanyi, and Simon, 2005) contains structures of all known transmembrane proteins and fragments along with their most likely position relative to the membrane planes as calculated by the TMDET algorithm, which uses a combination of hydrophobicity scores and structural features (see Section “Identification of Membrane Proteins Using 3D Structural Data”). The PDB_TM database is organized similarly to the PDB and the properties described in each entry include the TMDET score on which the selection of the position in the membrane was made, the type of protein according to the secondary structure of its membrane-spanning residues determined by DSSP (α-helical, β-barrel, or unstructured), further information derived from keyword searches in the corresponding UniProt and PDB files, the definition of the membrane planes, and the localization of each transmembrane sequence portion.

TABLE 36.2. Available Resources for Membrane Protein Identification and Classification

| Sequence, Structure, and Function Information Sources | ||

| Resource | Web Site | Information Type Included |

| MPDB (Raman, Cherezov, and Caffrey, 2006) | http://www.mpdb.ul.ie/ | 3D structure and function, all membrane proteins |

| Membrane protein of known 3D structures | http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html | Structure and function, all membrane proteins |

| Membrane protein of known structures | http://www.mpibp-frankfurt.mpg.de/michel/public/memprotstruct.html | Structure and experimental conditions, all membrane proteins |

| PDB_TM (Tusnady, Dosztanyi, and Simon, 2005) | http://pdbtm.enzim.hu/ | Structure and membrane location, all membrane proteins |

| OPM (Lomize et al., 2006b) | http://opm.phar.umich.edu | Structure and membrane location, all membrane proteins |

| GPCRDB (Horn et al., 2003) | http://www.gpcr.org/7tm/index.html | Fully comprehensive, GPCR family only |

| LGIC (Donizelli, Djite, and Le Novere, 2006) | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/compneur-srv/LGICdb/LGICdb.php | Sequence and structure, ligand-gated ion channels only |

| TCDB (Saier, Tran, and Barabote, 2006) | http://www.tcdb.org/ | Sequence and structure transporters only |

| PRNDS (Katta et al., 2004) | http://bicmku.in:8081/PRNDS/ | Sequence-based information, porins only |

| Automated Server for Identification and Phylogenetic Classification of Membrane Proteins | ||

| GPCR subfamily (Karchin, Karplus, and Haussler, 2002) classifier | http://www.soe.ucsc.edu/research/compbio/gpcr-subclass/ | SVM |

| GPCRpred (Bhasin and Raghava, 2004) | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/gpcrpred/ | SVM |

| PRED-GPCR (Papasaikas et al., 2004) | http://athina.biol.uoa.gr/bioinformatics/PRED-GPCR/ | HMM |

| SOSUI (Hirokawa, Boon-Chieng, and Mitaku, 1998) | http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/ | Physicochemical parameters (hydropathy, amphiphilicity, charges, and sequence length) |

| PRED-TMBB (Bagos et al., 2004b) | http://biophysics.biol.uoa.gr/PRED-TMBB/ | HMM |

| TMBETA-GENOME (Gromiha et al., 2007) | http://tmbeta-genome.cbrc.jp/annotation/home.html | SVM |

| BOMP (Berven et al., 2004) | http://www.bioinfo.no/tools/bomp | Pattern matching and aa preferences |

The Orientations of Proteins in Membranes database (OPM, http://opm.phar.umich.edu/) (Lomize et al., 2006b) provides a collection of membrane proteins from the PDB whose spatial arrangements in the lipid bilayer are calculated theoretically and compared with experimental data. Like PDB_TM, OPM provides a list of transmembrane proteins with their hydrophobic boundaries. Entries with the most complete quaternary structure or determined with the highest resolution are selected as representative models, whereas the other structures, such as mutants or different conformational states of the same protein, are included as “related PDB entries.” Complexes with many unassigned residues, such as low-resolution electron microscopy models, incomplete or nonfunctional assemblies (i.e., fragments), monomeric units of transmembrane functional multimers, NMR models derived from orientational constraints, such as ionophores, and theoretical models are excluded from the database.

Other Web Resources for Membrane Proteins

A few other Web-based resources are available that describe and collect membrane protein features, which are more comprehensive but more family specific (see Table 36.2). The GPCR database (GPCRDB (Horn et al., 2003)) is a comprehensive information system for G-protein-coupled receptors that provides much information, from cDNA and amino acid sequences to ligand binding constants and three-dimensional experimental and theoretical models. The Ligand-Gated Ion Channels database (LGIC) (Donizelli, Djite, and Le Novere, 2006) lists the nucleic acid and protein sequences of the extracellularly activated ligand-gated ion channels and provides multiple sequence alignments, some superfamily phylogenetic studies and available atomic coordinates of subunits. The Transporter Classification database (TCDB) (Saier, Tran, and Barabote, 2006) details a comprehensive classification system for membrane transport proteins and provides descriptions, TC numbers, and examples of over 360 families of transport proteins. The PoRiN Database Server (PRNDS) (Katta et al., 2004) collects data obtained by a statistically validated sequence-based search from UniProt and TrEMBL.

Finally, the MPtopo database collects membrane protein topologies that have been experimentally verified. It is therefore a very relevant and powerful resource because the reliability of predicted transmembrane sequence assignments for membrane proteins in the standard sequence databases has a significant intrinsic uncertainty.

CLASSIFICATION OF MEMBRANE PROTEINS

Classification of Membrane Protein Structures

The classification of membrane protein structures is difficult and still not completely resolved. In fact, to our knowledge, no current database classifies the available membrane protein structures into “homologous” structural families. Recent attempts to classify membrane protein structures systematically into families and superfamilies are available in the CATH (Pearl et al., 2005) and SCOP (Murzin et al., 1995) databases, both going beyond the simple division into a-helical and β-barrel proteins. However, the classification process is difficult, with many structures falling into singleton fold classes, especially channels and transporters, which are oligomeric transmembrane a-helical proteins with a variable number of transmembrane helices and/or oligomerization states, which defy simple clustering into structural families. As pointed out in a very recent review, a major obstacle to the development of effective methods to identify and classify distantly related membrane proteins is the lack of a structure-based “gold standard,” provided by SCOP and CATH for globular proteins (Elofsson and Von Heijne, 2007).

Most of the Web resources dedicated to membrane protein structure described in Section “Why is It Difficult to Solve Membrane Protein 3D Structures?” provide a partial or full classification of their entries, although none is based on 3D structural features. Proteins are usually classified according to a variety of features, including the position in the membrane (peripheral, if only the membrane surface is penetrated; monotopic, if proteins sink into the core but do not cross the membrane; bitopic, if proteins span the membrane only once; polytopic, if proteins span the membrane with more than one transmembrane segment), the number of transmembrane segments, the biological functions, the species, or the type of membrane.

Alternatively, membrane protein structures are classified according to membrane protein sequence subfamilies in various other resources. The GPCRDB classifies receptors in subfamilies using a chemical definition, that is, according to which ligand they bind. The LGIC database defines three superfamilies of channels according to their subunit structure: the receptors of the cys-loop families, such as nicotinic receptor and serotonin-activated anionic channels, made of five homologous subunits each with four transmembrane segments; the ATP-gated channels, made of three homologous subunits, each with two transmembrane segments; and lastly the glutamate-activated cationic channels, such as NMDA or AMPA receptors, that are made of four homologous subunits with three nonhomologous transmembrane segments. In the MPtopo database, entries are divided into three data sets, according to the source of the information used (i.e., 3D_Helix set— helix-bundle membrane proteins whose 3D structures have been solved and transmembrane segments are known precisely; 1D_Helix set—helix-bundle membrane proteins whose transmembrane helices have been identified by experimental techniques such as gene fusion, proteolytic degradation, and amino acid deletion; 3D_Other set—contains β-barrel and monotopic membrane proteins whose three-dimensional structures have been determined crystallographically). Finally, the TCDB provides an IUBMB classification scheme called the Transporter Classification system. The TC system is analogous to the Enzyme Commission (EC) system for classification of enzymes but also incorporates phylogenetic information, structural information, and even relationships with diseases. Transport systems are classified on the basis of five criteria, and each criterion corresponds to one of the five fields constituting the TC number for a particular type of transporter (e.g., A,B,C,D, and E). “A” is usually a number and corresponds to the transporter class (i.e., channel, carrier, etc); “B” is a letter and corresponds to the transporter subclass; “C” is a number and corresponds to the transporter family or superfamily; “D” is a number, corresponding to the subfamily in which a transporter is found, and finally the “E” corresponds to the substrate or range of substrates transported. Any two transport proteins in the same subfamily of a transporter family that transport the same substrate are given the same TC number.

Other Types of Classification of Integral Membrane Proteins

GPCRs represent the most explored class of membrane proteins and several studies involving their analysis, identification, and classification from sequence have been published, with corresponding programs often freely available for academic use (Inoue, Ikeda, and Shimizu, 2004; Filizola and Weinstein, 2005; Gao and Wang, 2006). Moreover, three Web-based resources for GPCR detection and family assignments are currently available. They employ pattern recognition machine learning approaches, that is, hidden-Markov-Models and support vector machines (SVMs) and are listed in Table 36.2. The GPCR subfamily classifier (Karchin, Karplus, and Haussler, 2002) is an SVM method developed to determine GPCR function from sequence and classify entries according to the subfamily to which they are predicted to belong. GPCRpred (Bhasin and Raghava, 2004) is SVM based as well and predicts protein families and subfamilies from the sequence dipeptide composition. Data sets used for the training of both GPCR Subfamily Classifier and GPCRpred were derived from the GPCRDB information system, which organizes GPCRs into a hierarchy of classes, class subfamilies, and types, according to the ligand they bind. PRED-GPCR (Papasaikas et al., 2004) is a program for the recognition and classification of GPCR members at the family level. It is HMM based and includes profiles for 67 well-characterized GPCR families. The employed classification system is based on the TiPs pharmacological receptor classification (Alexander et al., 1999) and on GPCRDB. In addition, PRINTS (Mulder et al., 2007), which is a compendium of protein fingerprints (conserved sequence motifs) used to characterize protein families, has proven to be an effective classifier for GPCRs.

Finally, one Web-based resource, called SOSUI, is available for the classification and secondary structure prediction of helical membrane proteins (Hirokawa, Boon-Chieng, and Mitaku, 1998). However, in this case the classification only provides a discrimination of membrane proteins from water-soluble proteins.

A few studies have been published to identify all β-barrel membrane proteins in a genome, based on the analysis of sequence composition, secondary structure prediction, and architecture of known structures (Liu et al., 2003; Bagos et al., 2004a; Bagos et al., 2004b; Berven et al., 2004; Gromiha, 2005; Park et al., 2005). In particular, BOMP, PRED-TMBB, and TMBETA-GENOME are available as online resources (Table 36.2). BOMP uses a simple pattern matching associated to an amino acid likelihood score. PRED-TMBB and TMBETA-GENOME implement machine learning techniques, HMM and SVM, respectively, and are based on sequence and secondary structure information. Moreover, TMBETA-GENOME includes a collection of the annotated β-barrel membrane proteins for all the completed genomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Membrane proteins represent a very important class of proteins and are responsible for maintaining the homeostasis and responsiveness of cells by mediating a wide range of fundamental biological processes. They are found in biological membranes, which are composed of phospholipid bilayers impermeable to polar molecules and inhabit a physicochemical environment very different from polar media like the cytoplasm and periplasm. Membrane proteins are highly insoluble and unstable in aqueous solutions, so that severe experimental problems are associated with their study. Consequently, the amount of available structural data is still scarce, although the picture recently being improving, with 775 membrane protein structures corresponding to 125 different proteins currently available in the PDB.

The recent determination of several new structures has allowed some progress to be achieved in the development of bioinformatics methods for the prediction of membrane protein 2D and 3D structures. Current bioinformatics tools mainly focus on the identification of transmembrane proteins and the prediction of their 2D structure and topology (see Table 36.1) and are based on machine learning techniques. In particular, HMMs have proven to be the best performing methods for the prediction of both helical and β-barrel protein topology with accuracy higher than 70%. Moreover, new experimental topology data have been shown to increase the prediction accuracy by about 20% but its use is still limited due the paucity of available information. Very few methods, mainly based on ab initio/de novo approaches, have been developed specifically for the prediction of membrane protein 3D structures. However, methods for the prediction of membrane protein 3D structural features, such as re-entrant loops and proline-induced helix kinks, have been recently developed (2.5D structure prediction), allowing a step forward toward more reliable predictions of membrane protein 3D structures.

Currently available Web-based resources for membrane proteins, as summarized in Table 36.2, include lists and collections of data, from cDNA sequences and protein sequences to 3D structures, and sequence- and/or function-based classification schemes. They are often family-centric, and to our knowledge, a fully comprehensive resource including the most important features for all membrane protein families is not yet available. However, many new structures are expected in the next few years, in part due to the efforts of the Structural Genomics projects dedicated to membrane proteins. It is our belief that the new experimental information will improve existing methods and will encourage the development of novel prediction methods and automated and complete resources for a full computational analysis and classification of membrane protein structures.