38

THE SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPACTS OF PROTEIN DISORDER AND CONFORMATIONAL VARIANTS

INTRODUCTION

Protein disorder is a topic worth attention from the structural bioinformatics community largely for the technical challenges it presents to the field, but also for its biological and functional implications. The success of structural genomic efforts using X-ray crystallography depends on overcoming several potential bottlenecks (Chapter 40), one of which is the formation of protein crystals that can be obstructed by the presence of highly flexible and disordered regions. Despite precluding the number of structures that can be obtained, thus impacting the coverage of protein space, our current generalized understanding of disordered regions is a result of structural bioinformatics efforts that were able to extract and analyze patterns associated with these regions. These disorder predictors have been proven to be useful in advancing our understanding of disordered regions with potential impact to improve the success rate of structural genomics efforts, particularly those focused on eukaryotic proteins (Oldfield et al., 2005b).

The importance of resolving differences observed in conformational variants within protein families and understanding their impacts is also a rising issue. Most structural genomics efforts aim to solve a representative structure for each protein family to maximize the coverage of protein space with particular focus on identifying new protein folds. However, it is equally important to understand structural changes that result from sequence differences introduced by a few single point mutations, insertions, and/or deletions since it can have a large functional impact. Furthermore, the structural information recorded in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) is often overlooked as a macroscopic view of a collection of microscopic ensembles that give rise to the observed protein structure. In other words, the observed protein structure is not the only conformation adopted by the protein. In fact, most observed biological phenomena are a macroscopic consequence of the collective microscopic states. Understanding the differences in the microscopic states and how the changes impact the macroscopic event is currently addressed in several ways that will be discussed.

By exploiting the technical weakness in structural data, researchers have been able to gain insight into the potential biological significance of these otherwise poorly characterized disordered regions (Ringe and Petsko, 1986). Recognition for the importance of protein disorder in biological function came around the late 1970s when disordered regions seem to reoccur within particular features of enzymes such as the zymogens of pancreatic serine proteases and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases (Blow, 1977). In light of these investigations, the hypothesis presented at the time was that the reactivity and specificity are associated with more rigid structures while disordered regions may be involved with control of the function. Since then, many functional roles of disordered regions including regulatory control have been implicated through experimental investigation of these regions, statistical mechanics, and structural bioinformatics approaches.

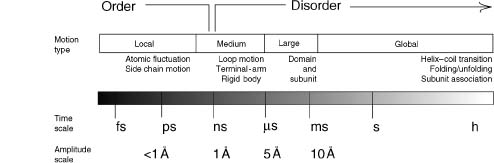

While the topics of protein disorder and conformational variations are intrinsically related to protein flexibility, these topics warranted a separate chapter from “Protein Motion: Simulation” (Chapter 37) largely because it deals with a time frame and complexity beyond what is captured by protein dynamic modeling approaches (Figure 38.1). Molecular dynamics simulations have been used to study conformational disorder and variants of proteins with limitations (Torda and Scheek, 1990; Kuriyan et al., 1991; Fuentes et al., 2005). Longer molecular dynamic simulations are reserved for smaller proteins or are otherwise restricted to a short time frame within limits of nanoseconds for larger proteins. As such, the observed conformational changes with these simulations will also be limited. The topics of disorder and conformational variations discussed here extend beyond what can be offered by molecular dynamic simulations, although various strategies such as the use of Monte Carlo sampling (Lindorff-Larsen et al., 2004) and averaging over a few samples of generated conformers while using experimental constraints (Kemmink et al., 1993; Bonvin and Brunger, 1995) have been used to address this issue. Coarse-grained dynamic modeling addresses molecular motion beyond the time frame limitations of classical molecular dynamics. However, a systematic analysis between disordered regions and the modeled large-amplitude fluctuating regions using these rigid-body based approaches needs to be conducted.

Figure 38.1. Range of protein dynamics and structural observation. Protein flexibility lies on a spectrum where the fluctuations occur at a range of different time scales. Ordered structures can be visualized with simulated motion limited to the nanosecond range. Protein fluctuations beyond this range are viewed as being disordered and lacking stable structures.

In this chapter, we briefly discuss the experimental methods used to study disordered regions and highlight the computational resources that have largely fueled the advancement of this field by providing many of the current generalized observations. The biological importance of protein disorder and conformational variations as they exist in microscopic ensembles will also be examined in more detail. We attempt to create an introductory chapter to the subject and apologize if not all research efforts are represented in this otherwise rapidly growing field.

PROTEIN DISORDER: UNDERSTANDING THE REALM OF “INVISIBLE”

Defining Protein Disorder

Before proceeding, we must first make clear that the field currently lacks a unifying definition when discussing protein flexibility, disorder, and intrinsically unstructured proteins. These terms are often used interchangeably due to the qualitative nature of the definition and can leave readers with some confusion if the slight distinctions are not clarified. Other disorder-related terms that have been coined in the field are intrinsic coils, random coils, unfolded proteins, molten globules, and premolten globules as examples to define protein states that are not natively folded. These terms are often refer to the global state of the protein rather than specific regions within the protein structures that are disordered. Without setting the standard nomenclature for the field, we will clarify by defining the usage of “disorder” in this chapter as regions in the protein structure where the equilibrium position of the backbone, along with the dihedral angles, that have no specific values and vary significantly over time.

When evaluating and using disorder predictors, it is also important to have a clarified view of how these regions were defined in the training of disorder predictors and other efforts to understand these regions. Some sequence-based disorder predictors, such as PONDR (Romero et al., 1997) and DISOPRED (Jones and Ward, 2003), were trained on disorder defined as missing regions in the X-ray crystallographic structures. This definition is also used to benchmark the performance of disorder predictors by evaluators in CASP experiments (Chapter 28). However, other predictors such as GlobPlot (Linding et al., 2003b) and DisEMBL (Linding et al., 2003a) are trained on definition based on a temperature factor (B-value) threshold to define disorder in X-ray crystal structures. Finally, other subtle differences in disorder predictors should be considered such as RONN (Yang et al., 2005) and Wiggle (Gu, Gribskov, and Bourne, 2006). RONN incorporates additional use of curated information from homologous proteins to make predictions regarding disordered regions, and Wiggle was trained on a data set where flexible regions are defined using dynamic modeling techniques. These subtle distinctions should be noted when considering which predictor would best serve the scientific question at hand.

Prevalence of Disordered Protein Regions

Flexible and disordered regions present two challenges to our understanding of protein structures. Aside from being unable to resolve atomic coordinates for these regions to understand the structure, the regions also interfere with the formation of protein crystals needed to collect X-ray diffraction data. Disordered regions are often addressed by removing them from proteins targeted for structure determination. These disordered regions can also be detected using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR—Chapter 5), but the structure of these regions cannot be easily determined due to the increased conformational space sampled by the disordered regions. An analysis of a nonredundant subset of the PDB shows that ~7% of the complete sequences, as deposited in the Swiss-Prot Database, contained no disordered regions (Le Gall et al., 2007). A number of sequences where >95% of the protein is resolved structurally comprise about ~25% of the data set, a surprisingly small count that illustrates the prevalence of disordered regions within protein structures.

The presence of disordered regions is not a technical artifact and several different techniques have been employed to study this phenomenon. Early studies used spectroscopic techniques such as infrared circular dichroism (CD), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and optical rotary dispersion(ORD) to detect native and nonnative structures that may form within the disordered regions. More recently, NMR and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) have been used to provide quantitative data about disordered and denatured proteins (Kern, Eisenmesser, and Wolf-Watz, 2005; Mittag and Forman-Kay, 2007; Sasakawa et al., 2007; Tsutakawa et al., 2007). These experimental approaches can provide quantitative data that can be incorporated into the calculation of the observed conformational ensembles in solution to determine the structural information about denatured, unfolded, and intrinsically disordered proteins. Hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange mass spectrometry (Chapter 7) has also been used to study dynamic processes such as the role of transient structural disorder as a facilitator of protein-ligand binding (Xiao and Kaltashov, 2005). These experiments have detected structural formations within these disordered regions, and these structures have been associated with functional implications.

With the development of sequence-based predictors, the prevalence of disordered regions in organisms have been investigated across the three kingdoms of life (Oldfield et al., 2005a; Ward et al., 2004). The frequency of native disorder was calculated for several representative genomes and found to have increased content in eukaryotic proteins (33.0%) compared to 2.0% and 4.2% of archaean and eubacterial proteins, respectively (Ward et al., 2004). The analysis showed that proteins containing disorder are often located in the cell nucleus with functional association to regulations of transcription and cell signaling. In a separate study, an increase in intrinsic disorder content has been observed in regulatory cell signaling, cytoskeletal, and human cancer-associated proteins (Iakoucheva et al., 2002). Disordered regions are currently being curated into a database, DisProt (Sickmeier et al., 2007), which contains 472 proteins and 1121 disordered regions as reported for release 3.6 (June 29, 2007).

Computational Approaches to Understanding Protein Disorder

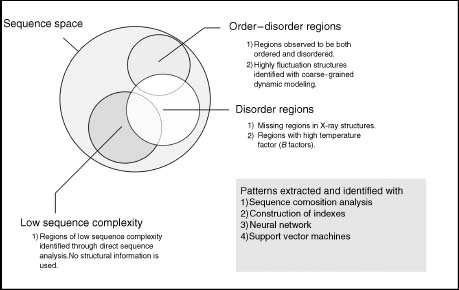

The computational tools that have been developed to predict regions of protein flexibility and disorder range from the use of simple sequence complexity profiles to complex machine learning infrastructure schemes such as the neural network and support vector machines (SVMs) (Figure 38.2). The successful development of these tools is attributed to the fact that sequence signatures of protein disorder are present. The popular choice of training set to construct these predictors often use reported missing residues in X-ray crystallographic structures, but reported temperature factors (B-factors) and NMR characterized disordered regions have also been used. First we will discuss algorithms that do not use structural information to identify and understand disordered regions. This is achieved by either examination of the sequence space only or focusing on residues in which the structure cannot be resolved. Then we will follow with alternative strategies that use temperature factors in X-ray structures, the incorporation of homology information, and coarse-grained dynamic modeling to guide the training and disorder definition process. This short overview of disorder predictors will reflect the ongoing research efforts and common strategies employed to develop sequence-based identification of disordered regions.

Figure 38.2. General strategies to predict the disorder sequence space. Schema of various strategies used to identify and understand the sequence space of disordered regions. The differences stem largely from howthe disordered regions were defined and the underlying infrastructure for analysis and prediction tool development. Within all ofthe sequence space, a subset of sequence space will be associated with regions with low complexity, detected disordered, or those transitioning between an ordered and a disordered state. Overlaps can occur between the subsets.

SEG is a successful algorithm that identified unstructured regions by examination of the changing variation in sequence complexities within the sequence database (Wootton and Federhen, 1996). For a window length L and an N-residue alphabet, the compositional complexity for a given residue is

where Ω is the multinomial coefficient  Alternative formulations that resemble Shannon’s entropy to measure sequence

have also been used. After identifying low sequence complexity regions, the second stage of this

algorithm constructs an optimal subsequence to evaluate the probability of occurrence of the observed

pattern that is calculated as

Alternative formulations that resemble Shannon’s entropy to measure sequence

have also been used. After identifying low sequence complexity regions, the second stage of this

algorithm constructs an optimal subsequence to evaluate the probability of occurrence of the observed

pattern that is calculated as

where F is the combinatorial expression  ! that yields the frequency of observing the sequence composition with this

complexity and rk is the count of the number of

times the complexity state is observed in the window. This probability of occurrence has been

precomputed into a table that serves efficiently as an index to identify these regions. Thus, SEQ not

only identifies low complexity sequence regions but also determines whether these identified regions are

significant rather than a random occurrence. The success of this approach hinges on the assumption that

disordered regions have low sequence complexities. However, many disordered regions are not detected by

SEG and therefore suggest that features other than sequence complexity are involved.

! that yields the frequency of observing the sequence composition with this

complexity and rk is the count of the number of

times the complexity state is observed in the window. This probability of occurrence has been

precomputed into a table that serves efficiently as an index to identify these regions. Thus, SEQ not

only identifies low complexity sequence regions but also determines whether these identified regions are

significant rather than a random occurrence. The success of this approach hinges on the assumption that

disordered regions have low sequence complexities. However, many disordered regions are not detected by

SEG and therefore suggest that features other than sequence complexity are involved.

To detect other disordered regions, PONDR is the first disorder predictor that uses a design of two feed forward neural networks to make predictions using several attributes such as the fractional composition and hydropathy for the 20 amino acids (Romero, Obradovic, and Dunker, 1997; Romero et al., 1997). Unlike early flexible predictors, this predictor was trained on a data set of eight- and seven-residue-long disordered regions defined by X-ray and NMR experiments, respectively. The regions were defined as having either (1) no resolvable atomic coordinates and therefore declared as missing in the PDB files of X-ray structures or (2) extensively characterized as disorder with the use of NMR techniques. Predictions were made using raw input features extracted for the sequence and smoothed out with a second predictor. Since the initial development, PONDR is now available as a series of eight different predictors that identify different “flavors” of disorder (Vucetic et al., 2003) indicating that disordered features have distinctive sequence characteristics within each subclass. The success of this initial development of disorder predictors on such a small training data set is surprising and may be illuminative of sequence properties to be further discussed in the subsequent section.

DISOPRED (Jones and Ward, 2003) is another predictor that is also based on the use of a neural network but uses sequence profiles generated by PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) as input features to make predictions with a postfilter that takes into account the confidence of secondary structure predictions. Often predictions are made based on physicochemical properties of the amino acid, but DISOPRED uses instead the amino acid identity, composition, and evolutionary conservation. Thus, the physicochemical properties are not explicitly captured in the input features although it may be implicitly represented. The inclusion of input features that represent evolutionary conservation was inspired when secondary structure predictors (Chapter 29) were improved using this information. The use of evolutionary information helps capture conserved features, or lack there of, between protein homologues. DISOPRED reports an accuracy of 90%, but the use of accuracy to measure success can sometimes be misleading, especially when the data set is unbalanced in class frequencies. In this case, the data set contains a much greater number of ordered residues than disordered examples, an important consideration when evaluating any predictor. Another measure to evaluate predictor performance is the use of Matthews’ correlation coefficient (MCC) that DISOPRED reports to be 0.34, suggesting an overpre-diction of disordered regions.

RONN is another neural network algorithm that incorporates evolutionary information to improve disorder prediction. Instead of using multiple sequence alignments and sequence similarity directly, this algorithm compares the sequence to homologous proteins with characterized and annotated disordered features (Yang et al., 2005). The alignment scores of the sequence to a database of known order and disorder segments are used as the input features for prediction. This interesting strategy resulted in improvements that reduced the number of incorrect classification of residues in either the ordered or the disordered structural class.

More recently, POODLE-L (Hirose et al., 2007) implemented a two-layered support vector machine that uses physicochemical properties as input features and reports an improved performance with an MCC value of 0.658. The source of improvement is difficult to ascertain, although it may be safe to speculate that either the use of the SVM for extraction or a more focused training set is the underlying source. While successful discrimination does depend on the correct selection of input features that properly represent critical properties of disorder regions, the physicochemical properties used in this predictor have also been used by other predictors. Thus, it is unlikely that this would be the source of significant improvements.

Strategies that use relatively simpler algorithms compared to machine learning approach have also been used to efficiently identify these regions. GlobPlot2 (Linding et al., 2003b) uses propensities for amino acid to be in either an ordered or a disordered structure, thus creating a disorder propensity index. Different propensity indexes and scales were calculated to accommodate the different definition of disorder in the field and therefore will make predictions accordingly. IUPred (Dosztanyi et al., 2005a; Dosztanyi et al., 2005b) uses a low-resolution energetic force field based on the pair-wise interacting residues observed in structures. The total pair-wise interaction is estimated based on a quadratic form in the amino acid composition of the protein.

Developments of specialized disorder predictors to identify particular features of disordered regions have also been made. The PONDR series of predictors have effectively achieved this by constructing predictors that identify pattern subsets on features such as the length of disordered regions. Wiggle is another specialized predictor that identifies flexible regions having functional importance. Functional flexibility was defined as regions in the protein where (1) the fluctuating motions exceed the mean fluctuation by more than one standard deviation and (2) these fluctuations are involved in correlated motion. The use of this definition successfully identified regions such as recognition loops, catalytic loops, and hinges in a training data set where protein motion was obtained using a coarse dynamic modeling technique.

Finally, various consensus and integrated strategies that incorporate different predictors to improve disorder prediction have been developed. Consensus strategies have improved structure prediction methods in the recent years and therefore will likely be the case for disorder prediction. This approach often requires interpretation of results by the user to decide between prediction results from different methods since the integration of methods does not include an automated decision-making feature. Two such examples of integrated servers that are available to the community are PrDOS (Ishida and Kinoshita, 2007) and iPDA (Su, Chen, and Hsu, 2007).

Sequence Basis for the Biophysical Property of Ordered and Disordered Regions

Decoding the sequence space is at the heart of many fields, and understanding how the biophysical properties of proteins are encoded in the sequence is imperative to making inferences about the protein structural fold and function. For example, the amino acid hydrophobicities determined from several biophysical and theoretical experiments have been used to make predictions for higher order protein features such as secondary structure (Palliser and Parry, 2001). Unfortunately, advances in the field are still needed before an accurate sequence-based biophysical description of proteins is available to the community. Reoccurring amino acid bias and sequence patterns found within particular features of proteins are often examined in hopes to glean some insight into a biophysical explanation. In regard to protein disorder and flexibility, variances in protein sequences have been examined and regions of low sequence complexity have been identified to preclude structural formation (Wootton and Federhen, 1993; Wootton and Federhen, 1996). Glutamine-rich, glycine-rich, and arginine-rich sequences are often a part of this class of low sequence complexity regions with an occasional periodicity nature of repeating units. Regions enriched in proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine (PEST) are also associated with protein disorder.

The arrival of disordered predictors has allowed researchers to gain more insight into sequence bias and patterns associated with ordered and disordered structures through both the training process and subsequent analysis of the sequence space identified with these algorithms. Initially, there were some concerns that the disorder predictors were making predictions based on low complexity features similar to those identified by SEG. Instead, it has been demonstrated that amino acid composition differed between low complexity, disordered, and ordered regions (Romero et al., 2001). Disordered regions have been found to contain higher levels of R, K, E, P, and S amino acids with lower levels of C, W, Y, I, and V compared to ordered regions. Based on this analysis of change in amino acid frequency between ordered and disordered structures, the residues can be ranked from disorder promoting to order promoting as follows: K, E, D, P, N, S, Q, G, R, T, A, M, H, L, V, Y, I, F, C, W. Such ranking suggests that the amount of flexibility, and hence disorder, can be tuned depending on which residues are used and in what order.

Sequences that adopt both an ordered and a disordered structure depending on the observed conformational state have been investigated to understand how such a balance could be achieved (Zhang et al., 2007). These regions are coined as having “dual personality” and have been collected from proteins with multiple X-ray structures in different conformations. Regions that are invisible in one conformer but resolved in another were defined as having ambivalence for either ordered or disordered regions. Residues were clustered into three major groups based on their relative abundance for disordered, ordered, or ambivalent regions. The first group contains hydrophilic and small amino acids (K, E, S, G, and A) that are largely associated with disordered regions. The second group consists mostly of hydrophobic resides (M, H, Y, I, F, C, and W) that are found in abundance within ordered regions. Finally, the third group consists of mostly hydrophilic amino acids (D, T, Q, N, P, and R) that are found in fairly equal propensities for ordered and disordered regions. These clusters are in some agreement with what have been identified by Romero et al. although there are differences. Wiggle (Gu, Gribskov, and Bourne, 2006) shows a different scenario of amino acid preferences for these regions ranked in the following decreasing order: E, K, Q, R, D, P, N, S, G, A, L, T, W, H, M, Y, F, C, V, I. This ranking shows correlation with the consensus hydrophobicity index (Palliser and Parry, 2001). Although some general trends can be observed between the different analyses, the lack of agreement suggests that more work is needed to understand how the biophysical property of protein disorder is encoded in the sequence.

Investigation of higher order sequence associations with disordered regions has identified at least two nonrandom reoccurrence of patterns based on amino acid identity or physicochemical properties (Lise and Jones, 2005). The analysis was conducted on segments up to eight residues and repeated observations of proline-rich or charged segments in disordered regions were identified. Although rather restrictive parameters were used in this analysis, this examination shows that patterns associated with disordered regions are much simpler compared to those found in ordered regions and rarely contained two different amino acids. These patterns are not inclusive of all the possible patterns that may be found in disordered regions.

Despite the low complexity of these local sequence patterns, the nonrandom occurrence of these patterns reveals that biophysical properties of disordered structures are dependent on both the sequence composition and order. Furthermore, different types of disordered regions have been identified with a dependency on segment length (Vucetic et al., 2003). Subclasses of disordered regions have been identified with different functional associations. More recently, these thermodynamic features of unfolded regions were recently surveyed using a structure-based thermodynamic model (Wang et al., 2008). The results show that, unlike natively folded proteins, the thermodynamics of unfolded regions is dominated by local sequence contribution and is sensitive to the composition and order of the sequence. The local dependence of the disorder thermodynamics also provided some insight regarding why certain biophysical properties of the natively folded state may be retained.

In the process of understanding the sequence basis for protein disorder, it is also important to understand the contributions of evolutionary pressures that select for the disordered state. Although evolutionary conservation has been included as one of the input features to help disordered predictors discriminate between the different sequence types, strict conservation may not necessarily be a critical feature of disordered regions. Disordered regions have been cited to evolve rapidly (Brown et al., 2002) and observed to have increased alternative splice sites that generate more functional diversity in multi-cellular organisms (Romero et al., 2006). Evidence that disordered regions can be identified with a reduced set of the amino acid alphabet further supports the notion of weak evolutionary selection (Weathers et al., 2004). Consequently, the robustness to substitutions simplifies the combinatorial possibilities of amino acid patterns; thus, it may be possible to decode a direct linkage between sequence and the biophysical properties of disordered regions.

Biological Consequences

In addition to paving way to a better understanding of the sequence space, many hypotheses that generalize the biological and functional significance of disordered regions in proteins stem from computational analysis with disordered predictors. Detection of the prevalence of disordered regions across the different genomes mentioned earlier is one example of how the disorder predictors have been applied. At least 28 functional roles of disorder proteins have been identified and can be grouped into four main functional classes: (1) molecular recognition, (2) molecular assembly, (3) protein modification, and (4) entropic chain activities (Dunker et al., 2002; Radivojac et al., 2007). These functional classes largely appear to reflect intermolecular function linked to regulatory processes, but the biophysical properties of disordered regions are also important for protein folding, allostery, and catalytic processes that are not necessarily captured by this functional classification system presented by Dunker and colleagues. Patterns detected within disordered regions have also been used to functionally classify proteins, particularly in cases where there are no structural homologues (Lobley et al., 2007).

First, disordered structures provide an advantage in molecular recognition by promoting promiscuous, transient binding for several targets and therefore help to increase the complexities of protein interaction networks (Tompa, Szasz, and Buday, 2005). The resulting promiscuous bindings allow these proteins to have multiple cellular roles (Sandhu and Dash, 2006). Binding mechanisms used by disordered regions rely more on hydro-phobic-hydrophobic interactions with more intermolecular contacts that cover a much larger surface area of the target protein compared to ordered binding sites (Meszaros et al., 2007; Vacic et al., 2007). This is often achieved through a continuous segment that sometimes contains preformed structural elements where the native structure is fully induced after binding to the substrate (Fuxreiter et al., 2004). Investigation of underlying linear motifs important for recognition suggests that order favoring sequences are grafted between disordered regions that serve as a carrier (Fuxreiter, Tompa, and Simon, 2007).

Disordered regions have been identified to be important for complex formation for larger complexes such as the viral capsid, bacterial flagellar system, cytoskeleton, ribosome, and clathrin coat (Namba, 2001; Dafforn and Smith, 2004; Ward et al., 2004). A significant correlation was observed between predicted structural disorder and the number of proteins assembled into complexes conducted on E. coli and S. cerevisiae proteins (Hegyi, Schad, and Tompa, 2007). The larger complexes show a higher average of disorder content with longer predicted segments. These results are in agreement with the idea that disordered regions are involved with protein binding and molecular recognition that could be one contributing mechanism to complex formation. Alternatively, disordered regions in complex formation may simply serve as linkers between well-formed domains. The hypotheses presented here have been based on bioinformatics analysis and need to be further investigated experimentally.

Other disordered regions have been cited to act as entropic chains comprising a functional class that includes linkers, bristles, springs, and clocks (Dunker et al., 2002). This functional class is relatively less studied and appears to play a role in introducing a level of organization in time and space. For example, linkers serve to link domains while bristles help keep molecules apart through molecular exclusion. Springs are segments that have restoring forces to favor a randomized fold and become restricted when stretched as observed in titan molecules found in muscle fibers (Labeit and Kol-merer, 1995; Kellermayer et al., 2000) and elastin (Pometun, Chekmenev, and Witte-bort, 2004). The property of increased flexibility for disorder regions has been hypothesized to be exploited and used as a “random generator” that effects the timing of biological process such as determining the closure of a voltage-gated channel (Wissmann et al., 1999; Wissmann et al., 2003).

The aforementioned four categories are not exclusive of each other nor are they comprehensive of all possible functions associated with disordered regions that are still yet to be fully understood. For example, a highly disordered loop in cochaperonin GroES is important for binding to GroEL and has also been suggested to facilitate the cycles observed for chaperonin-mediated protein folding through modulation of binding affinity without affecting specificity (Landry et al., 1996). This example serves to suggest that a certain level of flexibility necessary for function is being evolutionarily selected and conserved.

Retaining this balance of flexibility is also evident in the presence of disordered regions that are important for catalysis and allostery. Changes in local segmental flexibility were studied in the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase using site-directed labeling and fluorescence spectroscopy (Li et al., 2002). The backbone located around the B-helix was found to have reduced flexibility only when the substrate and pseudosubstrate are bound to the catalytic domain. This stage of the catalytic cycle coincided with the phosphoryl transfer transition suggesting that internal disorder is important for this catalytic step. In another example using single-molecule enzymatic assays, DNA was hydrolyzed by lambda exonuclease with contributions from sequence-dependent factors and disorder arising from conformational changes (van Oijen et al., 2003).

Although popular competing allosteric models are based on changes observed in rigid structure bodies, alternative views propose that proteins can be regulated through changes in protein dynamics. The Cooper-Dryden model is a mathematical formulation that shows protein allostery can be achieved in the absence of structural change (Cooper and Dryden, 1984). The dimeric CAP that binds to cAMP is an example of the Cooper-Dryden model where changes were observed in the dynamics of the system but not the structure (Popovych et al., 2006). In another example, dynamics is an integral part of the allosteric response initiated by a ligand-induced disorder to order transition in the adenylate binding loop of the biotin repressor, a transcription regulatory protein (Naganathan and Beckett, 2007). Changes in internal fluctuation between different stages of the activation cycle for cyclin-dependent kinase 2 have been identified to be associated with functionally important regions for regulation and catalytic activity with possible detection of entropy compensation mechanisms being utilized (Gu and Bourne, 2007). The advantages of coupled disordered regions for allosteric control have been demonstrated through statistical mechanics (Hilser and Thompson, 2007).

Disease Impacts

Disordered regions in proteins have been implicated in several diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. These pathogenic culprits contain disordered regions making it difficult to conduct structural studies with X-ray crystallography and NMR. NACP, for example, is a natively unfolded protein that seeds the polymerization of amyloid proteins leading to Alzheimer’s disease and impacts learning (Weinreb et al., 1996). It is suggested that the disorder regions allow for promiscuous binding and help potentiate protein-protein interaction that leads to the formation of these insoluble fibrils. Likewise, the tau protein found in Alzheimer’s tangles is characterized to have intrinsically disordered regions and leads to the formation of amyloid fibrils connected with disease progression (Skrabana, Sevcik, and Novak, 2006; Skrabana et al., 2006).

A subset of eukaryotic proteins related to cardiovascular disease (CVD) was examined and concluded to be enriched in disorder content (Cheng et al., 2006a). The analysis was conducted with PONDR disorder predictions, cumulative distribution function analysis, and charge-hydropathy plot analysis. Predictions for a-helical molecular recognition features suggest high abundance within these proteins. The percentage of CVD containing >30 residues predicted to be disordered was 57 ± 4% compared to 47 ± 4% of eukaryotic proteins in Swiss-Prot. The role of disorder in cardiovascular diseases needs to be further validated experimentally, but the finding does not come as a surprise since disordered regions are found to be associated with 66 ± 6% of signaling molecules, proteins that often have regulatory roles. Diseases are often a result of regulated processes gone awry.

Similarly, 79 ± 5% of human cancer associated proteins have been found to contain regions of disorder that are at least 30 consecutive residues in length (Iakoucheva et al., 2002). One example of an oncoprotein is the HPV16 E7 that is an extended dimer with a stable and cooperative fold but displays properties of natively unfolded proteins (Garcia-Alai, Alonso, and de Prat-Gay, 2007). The region of disorder is located at the N-terminal region of the E7 domain that contains two important sites for regulation: (1) the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor binding site for molecular recognition and (2) casein kinase II phosphorylation site that induces stabilization with phosphorylation. The structural plasticity of this region has allowed for adaptation to binding of a variety of protein targets and regulation of protein turnover. HPV16 is one of the human papillomavirus strains associated with high frequency to cervical cancer.

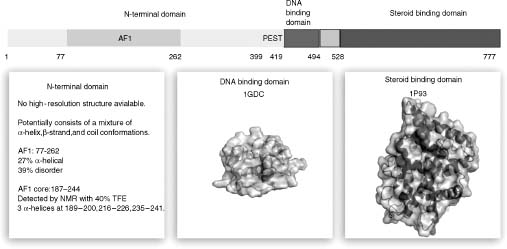

Case Study: Disorder in the Glucocorticoid Receptor

We present the structural anatomy of a transcription factor in more detail as an example to show how disordered regions may play a functional role (Figure 38.3). Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is a steroid binding nuclear receptor with well-defined domain boundaries (McEwan et al., 2007). The receptor is composed of three domains with structures available for the DNA and ligand binding domains located at the C-terminal end in the bound form. The N-terminal domain (NTD), on the other hand, is highly disordered and no high-resolution structural data are available to study this region that contains the transactivating AF1 domain (residues 77-262) involved in protein-protein interactions and regulation of transcriptional activity (Lavery and McEwan, 2005). However, significant structural data have been obtained using alternative methods such as biochemical analysis, circular dichroism, NMR, fluorescence, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Predictions for the structural content of this region have also been made using secondary structure prediction algorithms. These data collectively show that GR-NTD potentially consists of a mixture of α-helix, β-strand, and coil conformations. The disordered state of this region is hypothesized to provide a mechanism for allosteric control that allows for the adoption of different conformers that subsequently create different binding interfaces to interact with a multitude of targets. This feature may be particularly important for the AF1 region that is found to be 27% α-helical and 39% disordered in GR.

Figure 38.3. Anatomy of the glucocorticoid receptor. The structure of nearly half of the glucocorticoid receptor cannot be resolved due to intrinsic disorder in the N-terminal domain that contains the transactivating motif AF1. Low-resolution structural information shows a composition of α-helices in the AF1 core region (187–244). Residues 399–419 are found to contain the PEST motif of proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine that is associated with highly disordered regions. High-resolution structures are available for the DNA and steroid binding domains connected by a hinge.

The AF1 region may be an example of molecular recognition elements important for protein-protein interactions that use disordered regions as shuttles mentioned earlier. Through mutagenic studies, the induced formation of α-helical structures in this region has been correlated with the transactivation potential of GR (Dahlman-Wright et al., 1995; Dahlman-Wright and McEwan, 1996). This example demonstrates how regulation of transcriptional activity is achieved through modulating the order-disorder transition state that can be induced through a variety of factors such as DNA binding events (Lefstin and Yamamoto, 1998; Kumar et al., 1999) and even the presence of structure inducing osmolytes (Baskakov et al., 1999; Kumar et al., 2007). This strategy may be commonly used by all transcription factors as suggested by an analysis with PONDR that shows a relatively increased disorder content in transcription factors compared to other subsets of the eukaryotic proteins. Furthermore, the transcription activation regions are identified to have higher disorder content compared to the DNA binding region for the majority of the transcription factors (Liu et al., 2006).

PROTEIN CONFORMATIONAL VARIANTS AND ENSEMBLES

A discussion about protein disorder is really a discussion of protein conformational variants and the resulting ensembles that are the underlying basis for all biological phenomena and observations measured experimentally. A concept of ensemble highlights multiple possibilities that can be explored by proteins in alternative conformations rather than a single static structure, an important concept we wish to emphasize in this section. Consideration of alternative protein conformations expands not only the structural space, but also the functional space that can be regulated simply through partial unfolding that is observed as local protein disorder.

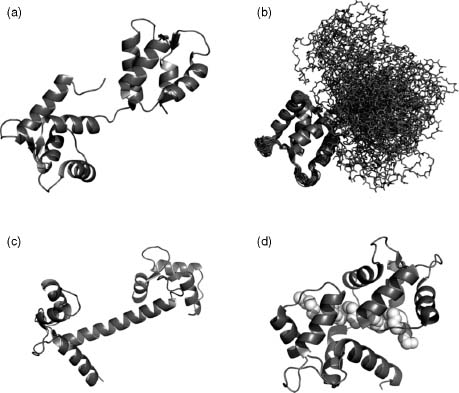

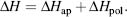

Structural variations are often appreciated when differences are observed between homologous proteins, but structural variations can also be observed for a protein at a single equilibrium state or between two states such as a ligand-bound and an unbound conformation (Figure 38.4). In the field of structural biology and structural bioinformatics, it is convenient to view high-resolution structural data as a single molecule, but we must remind ourselves that this interpretation is not the complete view. X-ray crystallographic studies are a collective contribution of all the protein molecules at equilibrium state found in the crystal lattice. Thus, the X-ray structure would represent the dominant conformation in the ensemble with regions of high temperature factors indicating a higher conformational variability. NMR, on the other hand, provides multiple solutions for conformations found in solution, thus instilling a greater appreciation in the structure inter preter for conformational variations. Protein dynamics and disorder leading to conformational variation is observed in NMR experiments as resonance overlap and peak broadening from conformational averaging and contributions from intermediate time scale dynamics.

Figure 38.4. Conformational variations in calmodulin. Comparison of (a) one conformational state of yeast calmodulin and (b) 31 states aligned at the N-terminal domain in the absence of calcium ions (PDBID: 1LKJ). (c) The bovine calmodulin adopts a dumbbell-like shape with calcium binding, which is different from the more globular structure found in yeast. (d) Calmodulin bound to a substrate (white spheres).

As an example of a protein that exists in many different conformational variations, we use calmodulin to illustrate the point (Figure 38.4). This regulator responds to calcium ions and exists in three main conformational states: (1) the apo-structure, (2) bound to calcium ions, (3) and bound to the target substrate. The apo-form of calmodulin has a structure of two globular domains connected by a hinge as observed in an NMR structure of calmodulin from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Figure 38.4a). Variations within a single state can be immediately observed in the apo-structure where alternative conformational states are aligned based on the N-terminal domain (Figure 38.4b). The C-terminal globular domain can exist in a different conformation relative to the N-terminal domain. Variations between homologues are observed in the calcium-bound bovine calmodulin with a helical linker region between the two domains whereas the yeast calmodulin adopts a more globular structure (Figure 38.4c). Finally, significant structural rearrangement is observed with binding to substrate. A multitude of structural conformations donned on by calmodulin represent some challenges that face the structural bioinformatics field.

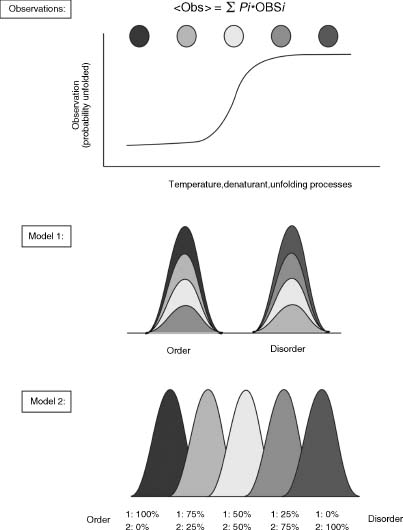

A biophysical explanation for protein disorder can be described by the underlying presence of conformational variations (Figure 38.5). An important concept that must be delivered here is that most experimental measurements of proteins are not single-molecule studies and therefore are collective contributions of all protein molecules in the solution. Thus, the observed measurement can be written as the summed contribution of each conformational state in the solution:

With this in mind, disorder in X-ray structure, for example, arises when there are many conformational variations that do not give rise to a single converged structure that is viewed as “ordered.” Sometimes highly ordered regions can be mistaken to be a disordered structure, particularly if large domain motions are involved such as those observed in calmodulin (Figure 38.4b).

The contribution of different states to the observation can be explained by one of the two models that represent the ratio of states differently (Figure 38.5). The first model assumes a discrete two-state conformation while the second allows for additional conformational states to be present. We illustrate the impact of the difference between the two models by applying it to the unfolding process of proteins, for example. In the first model, only the native (order) and denatured (disorder) states of the protein are allowed to exist in solution. The observed destabilization of proteins with increasing denaturant is then a result of the changing ratio between these two states in the solution. The probability of observing an ordered structure will decrease as the probability of observing a disordered structure will increase. In the second model, intermediate states containing partially unfolded conformers are allowed. Thus, the probability of observing each intermediate state as well as the native and denatured states contributes to the observation.

Figure 38.5. Ensemble-based description of protein disorder. (Top) Biological observations are the sum contribution of the different states in solution. The unfolding process of proteins, for example, can be described with one of the twomodels.Model 1 assumes two discrete states in solution in the native (order) conformation or denatured (disorder) conformation. The denaturation process is the changing ratio of these two states from one spectrum to the other. Model 2 allows from other intermediate conformations to contribute to the observation. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

The importance of an ensemble-based interpretation of the native state can be demonstrated through the use of COREX, a statistical thermodynamic model that uses free energy values that have been structurally parameterized (Hilser and Freire, 1996; Hilser et al., 2006). This experimentally validated model allows us to calculate the heat capacity (ΔCp), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) differences between the partially unfolded states and the native state (reported in kcal/K/mol). More importantly, the derivation allows for the interpretation of residue stability and contribution to the energetics of the ensemble that have provided insight into possible mechanisms for cooperative (Hilser et al., 1998) and allosteric processes (Hilser and Thompson, 2007).

Briefly, the relative Gibbs free energy of each possible conformational state adopted by the protein (ΔGi) is expressed in terms of the standard thermodynamic equation:

COREX obtains the relative Gibbs free energy using (1) a high-resolution structure and (2) a statistical thermodynamic model where the variables have been parameterized based on changes in the accessible surface area (ΔASA) between the native and the partially unfolded state. The enthalpic contribution to the state can be written as the sum of enthalpic contributions from apolar (ΔHap) and polar residues (ΔHpol):

The enthalpy change is related to ΔASA (Å2) in the following way and is parameterized at a reference temperature of 60°C, which is the median unfolding temperature for the data set of model proteins used:

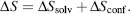

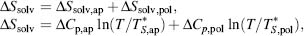

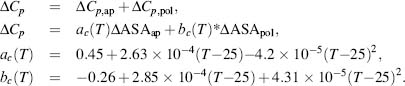

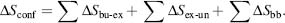

The entropy of the system is the sum of contributions from solvent ΔSsolv and conformational ΔSconf entropies:

The solvent entropy can be calculated with the knowledge of the heat capacity of the protein as derived:

where  and

and  are the reference temperatures at which the

hydration entropy is equal to zero (Baldwin, 1986; Murphy and Freire, 1992; D’Aquino et al., 1996). The

heat capacity is found to scale to ΔASA for temperatures up to 80°C as follows:

are the reference temperatures at which the

hydration entropy is equal to zero (Baldwin, 1986; Murphy and Freire, 1992; D’Aquino et al., 1996). The

heat capacity is found to scale to ΔASA for temperatures up to 80°C as follows:

Finally, to complete the calculation of Δs , conformational entropy is performed as follows:

The three contributions to conformational entropy are (1) ∑ΔSbu-ex: buried residues that become exposed with partial unfolding; (2) ∑ΔSex-un: exposed residues in the unfolded state; and (3) ∑ΔSbb: backbone entropy changes for residues that become unfolded. The entropy contributions of each amino acid have been determined and these values are used in the calculation (Lee et al., 1994; D’Aquino et al., 1996).

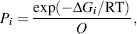

The relative Gibbs free energy of each state is calculated with these parameterized thermodynamic variables and will be important in determining the probability of observing such a conformational state in the ensemble. Under equilibrium conditions, statistical mechanics states that the probability of any given conformational state i (Pi) is given by the equation

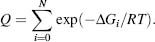

where the statistical weights, also known as the Boltzmann exponents (exp(–ΔG/RT), are defined by ΔGi relative to the gas constant R and temperature T. Q is the conformational partition function defined as the sum of the statistical weights of all the states accessible to the protein:

These probabilities reflect preferences for the protein to adopt a partially unfolded conformational state and can be extended to calculate the free energy contributions of each residue to the ensemble. Using the probability-weighted conformations in the generated ensemble, residue stability in the protein can be calculated as the ratio of residues in the folded and unfolded states:

where ∑ Pf;j and ∑ Pnf,j are the summed probabilities of all the states in which the residue is either folded or unfolded, respectively.

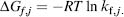

The free energy contribution of each residue to the ensemble can then be calculated:

The importance of this derived formalism is that it can be extended to study changes in energetic contributions at the residue level and provide insights into functional processes such as cooperativity (Liu, Whitten, and Hilser, 2006; Liu, Whitten, and Hilser, 2007; Pan, Lee, and Hilser, 2000) and allostery (Hilser and Thompson, 2007) by interpreting proteins as an ensemble of multiple conformations. Recent systems in which cooperativity has been identified and studied with COREX are dihydrofolate reductase and elgin C. The studies defined structural-thermodynamic linkages based on correlations in stability changes between residues in the ensemble as captured by kf,j. By examining these correlations, the model helps to define a mechanism for site-site communication, particularly between ligand binding sites and distantly located regions. The analyses suggest an alternative view to energetic coupling between residues when a clear, connected pathway of intramolecular interactions between them cannot be identified. The results also further emphasize the importance of entropic contributions that is often neglected.

While it is important to produce the correct high-resolution structure using fold recognition, homology modeling, and ab initio structure prediction approaches (Chapter 29-32), it is also equally important to construct other physically and chemically valid conformational states that can be sampled by the protein. Generating these structural variants that collectively produce a protein ensemble can be achieved with a variety of models, some more restrictive than others. Restrictive models are those that assume disordered or partially unfolded regions of the protein to adopt only coil structures (Bernado et al., 2005; Jha et al., 2005). A less restrictive model such as TraDES (Feldman and Hogue, 2000) is an unbiased conformational sampling method that generates plausible random structures allowing for both native and nonnative contacts. Other conformer generating methods including Rosetta (Simons et al., 1997) and CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) can also be used to predict structures in these disordered and highly flexible regions. The relative probabilities of the generated conformational variants that potentially populate the ensemble can then be calculated with experimental constraints using ENSEMBLE (Choy and Forman-Kay, 2001; Marsh et al., 2007). The population weight assignment is achieved with a pseudoenergy minimization process and a Monte Carlo algorithm. With these strategies we can now possibly begin to make interpretation of the functional consequences arising from these variety of conformational states.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Aside from the growing amount of literature on this topic, community recognition of the importance of understanding disordered region is signified by the inclusion of disorder predictor evaluation in CASP (CH 28). The first evaluation of disorder predictors appeared in CASP5 (Melamud and Moult, 2003) in 2002 with results showing successful detection for over half of the disordered residues in the blind set with a low rate of overprediction. However, proper evaluation of these predictors remains a challenge that still needs to be refined. This is to be expected due to both the varied definition and the existence of these different types of disordered regions. Furthermore, as noted by the assessors, the data set used for evaluation is skewed toward short disordered regions identified by missing residues in X-ray crystallographic structures. As such, caution should be taken when interpreting the performance of these results. In spite of the mentioned weaknesses, the evaluation process is a necessity because the predictors serve many useful purposes. The most recent benchmarking effort conducted at CASP7 in 2006 showed that in spite of the many new generations of disorder predictors, significant improvements in the performances have not be observed and variations are seen in their sensitivity and specificity for detecting these regions (Bordoli, Kiefer, and Schwede, 2007). Improvements in disorder predictors cannot be made without a systematic study of these regions and several experimental strategies using techniques that combine heat and acid treatment with mass spectrometry and/or 2D electrophoresis have been proposed to tackle this issue (Csizmok et al., 2007).

The applications of disordered predictors are not limited to target protein identification and elimination for structural genomic efforts. New applications include improved functional categorization of newly identified proteins (Lobley et al., 2007) and a potential role in improved drug design (Cheng et al., 2006b). The power of leveraging what we know about disordered regions will prove itself to be immensely valuable for the majority of the proteins that do not adopt a native fold. Currently, the function of about 35% of proteins cannot be categorized using homology-based assignment, leaving researchers with a large set of “hypothetical protein” drug targets with unknown function (Ofran et al., 2005). A systematic characterization of protein disorder can be achieved by combining the developments in improved computational and experimental analysis (Bracken et al., 2004).

Finally, the importance of understanding subtle differences in conformational variations, due to effects such as mutational events, has always been recognized by the structural bioinformatics field. New measures to better understand these variations are indicated by the goals presented to the structure prediction community proposed at the conclusion of CASP6 (Moult et al., 2005). The four challenges to overcome are to (1) model the structure of single-residue mutants, (2) model the structural changes associated with specificity changes within protein families, (3) improve refinement methods to produce a 0.5 Å root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) improvement in the Cα accuracy of models, and (4) devise a scoring function that will reliably pick the most accurate model of the possible candidate structures for new fold predictions. As the community addresses these challenges, an ensemble view of conformational variations should be kept in mind to understand functional consequences as well.

WEB RESOURCES

| Resource | References | URL |

| DisProt: the database of disordered proteins | Sickmeier et al. (2007) | http://www.disprot.org/ |

| DisProt: list of disorder predictors | Not published, a part of DisProt | http://www.ist.temple.edu/disprot/predictors.php |

| DISOPRED | Jones and Ward (2003) | http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/disopred/ |

| VLXT (PONDR) | Romero et al. (1997) | http://www.pondr.com |

| GlobPlot | Linding et al. (2003b) | http://globplot.embl.de |

| DisEMBL | Linding et al. (2003a) | http://dis.embl.de |

| PrDOS | Ishida and Kinoshita (2007) | http://prdos.hgc.jp/cgi-bin/top.cgi |

| RONN | Yang et al. (2005) | http://www.strubi.ox.ac.uk/RONN |

| Wiggle | Gu et al. (2006) | http://wiggle.sdsc.edu |

| PROFbval | Schlessinger et al. (2006) | http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu/services/profbval/ |

| iPDA: integrated protein disorder analyzer | Su et al. (2007) | http://biominer.bime.ntu.edu.tw/ipda/ |

| ENSEMBLE | Choy and Forman-Kay (2001) and Marsh et al. (2007) | http://pound.med.utoronto.ca/~forman/ensemble/ensemble.html |

| CNS | Brunger et al. (1998) | http://helix.nih.gov/apps/structbio/cns.html |

| ROSETTA | Simons et al. (1997) | http://www.rosettacommons.org/ |

| COREX/BEST server | Vertrees et al. (2005) | http://www.best.utmb.edu/BEST/ |