40

STRUCTURAL GENOMICS OF PROTEIN SUPERFAMILIES

Under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Protein Structure Initiative (PSI), the New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC) has applied its high-throughput X-ray crystallographic structure determination platform to systematic studies of two large protein superfamilies. Approximately, 15% of consortium resources are devoted to structural studies of protein phosphatases, which are classified as Biomedical Theme targets. A further ~ 15% of effort is devoted to structural studies of enolases (ENs) and amidohydrolases (AHs) as community-nominated targets. NYSGXRC efforts with the protein phosphatases have, to date, yielded structures of 21 distinct protein phosphatases: 14 from human, 2 from mouse, 2 from the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii, 1 from Trypanosoma brucei, the parasite responsible for African sleeping sickness, and 2 from the principal mosquito vector of malaria in Africa, Anopheles gambiae. These structures provide insights into both normal and pathophysiologic processes, including transcription regulation, signal transduction, neural development, and type 1 diabetes. In conjunction with the contributions of other international structural genomics consortia, these efforts promise to provide an unprecedented database and materials repository for structure-guided experimental and computational discovery of inhibitors for all classes of protein phosphatases. NYSGXRC efforts with members of the enolase/amidohydrolase superfmaily have yielded 58 structures of 34 distinct enolases and 18 amidohydrolases from a wide array of organisms. Our comprehensive survey of these a8β8 barrel structures aims to provide a database and materials repository for evolutionary studies of enzyme substrate specificity.

INTRODUCTION

In 2000, the National Institutes of Health—National Institute of General Medical Sciences established the Protein Structure Initiative with the goal to ’’make the three-dimensional atomic-level structures of most proteins easily obtainable from knowledge of their corresponding DNA sequences’’ to support biological and biomedical research (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Initiatives/PSI.htm). This pilot phase demonstrated the feasibility of the program and Phase II of the program, PSI-II, was launched in 2005, supporting four large-scale production centers to continue high-throughput structure determination efforts and six specialized centers to focus on specific bottlenecks such as membrane proteins and multicomponent assemblies (Table 40.1). More recently, these experimental efforts were supplemented by addition of two centers focused on enhancing comparative protein structure modeling, a PSI Materials Repository for centralized archiving and distribution of reagents and a PSI Knowledgebase for data sharing (Table 40.1).

Target selection represents a critical first step in the structural genomics pipeline, as it dictates the value of the ensuing structures. PSI-II employs a balanced target selection strategy that emphasizes the importance of large-scale structure determination and homology model generation, while exploiting the underlying infrastructure to address significant problems of biomedical relevance and to respond to the needs of the larger research community. Seventy percent of PSI-II efforts focus on the determination of structures with less than 30% amino acid sequence identity to an existing structure (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Initiatives/PSI.htm). This constraint is central to the overall goals of the PSI, as it is at approximately this level of sequence identity that homology modeling begins to fail due to difficulties in obtaining accurate primary sequence alignments. Fifteen percent of PSI-II activities are committed to projects nominated by the larger scientific community, with the remaining 15% devoted to a biomedically relevant theme developed by each of the four large-scale centers.

TABLE 40.1. NIGMS Protein Structure Initiative Centers

| Large-Scale Production Centers |

| Joint Center for Structural Genomics http://www.jcsg.org |

| Midwest Center for Structural Genomics http://www.mcsg.anl.gov |

| New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics http://www.nysgxrc.org/ |

| Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium http://www.nesg.org |

| Specialized Technology Development Centers |

| Accelerated Technologies Center for Gene to 3D Structure http://www.atcg3d.org |

| Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics http://www.uwstructuralgenomics.org |

| Center for High-Throughput Structural Biology http://www.chtsb.org |

| Center for Structures of Membrane Proteins http://csmp.ucsf.edu |

| Integrated Center for Structure and Function Innovation http://techcenter.mbi.ucla.edu/ |

| New York Consortium on Membrane Protein Structure http://www.nycomps.org |

| Homology Modeling Centers |

| Joint Center for Molecular Modeling |

| New Methods for High-Resolution Comparative Modeling |

| Resource Centers |

| PSI Materials Repository http://www.hip.harvard.edu/ |

| PSI Knowledgebase http://www.knowledgebase.rutgers.edu/ |

NYSGXRC

The New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (www.nysgxrc.org) has established a cost-effective, high-throughput X-ray crystallography platform for de novo determination of protein structures. NYSGXRC member organizations include SGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (www.sgxpharma.com), the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (www.aecom.yu.edu), Brookhaven National Laboratory (www.bnl.gov), Case Western Reserve University (www.cwru.edu), and the University of California at San Francisco (www.ucsf.edu). Together, scientists from these industrial and academic organizations support all aspects of PSI-II, including (1) family classification and target selection, (2) generation of protein for biophysical analyses, (3) sample preparation for structural studies, (4) structure determination, and (5) analyses and dissemination of results. NYSGXRC production metrics during the last full grant year (July 1, 2006-June 30, 2007) are as follows: generation of ~2060 target protein expression clones, ~1400 successful target protein purifications (all characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization and electrospray ionization (ESI)-mass spectrometry (MS), and analytical gel filtration), >360,000 initial crystallization experiments, > 106,000 crystallization optimization experiments, ~3100 crystals harvested, >600 X-ray diffraction data sets recorded, and 158 structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (www.pdb.org) and released. NYSGXRC averaged ~110 successful protein purifications per month and one structure deposition every 2-3 days. As mandated by the NIGMS, ~15% of NYSGXRC resources are devoted to structure determinations of Biomedical Theme targets, protein phosphatases from human, mouse, and various pathogens, and another ~15% of consortium resources are devoted to structure determinations of community-nominated targets drawn from the enolase/amidohydrolase superfamily. (The terms of the PSI-II award to the NYSGXRC explicitly forbid allocation of substantial resources to functional characterization of PSI targets.)

BIOMEDICAL THEME TARGETS: BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION

Protein kinases and phosphatases act in counterpoint to control the phosphorylation states of proteins that regulate virtually every aspect of eukaryotic cell and molecular biology. Protein phosphorylation is a dynamic posttranslational modification, which allows for processing and integration of extra- and intracellular signals. In vivo, protein kinases and phosphatases play antagonistic roles, controlling phosphorylation of specific protein substrates on tyrosine, serine, and threonine side chains. These reversible phosphorylation events modulate protein function in various ways, including generation of ’’docking sites’’ that direct formation of multicomponent protein assemblies, alteration of protein localization, modulation of protein stability, and regulation of enzymatic activity. Such molecular events modulate signal transduction pathways responsible for controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation, cell-cell and cell-substrate interactions, cell motility, the immune response, ion channel and solute transporter activities, gene transcription, mRNA translation, and basic metabolism.

Aberrant regulation of protein phosphorylation results in significant perturbations of associated signaling pathways and is directly linked to a wide range of human diseases (reviewed in Tonks, 2006). PTEN, the first protein phosphatase family member identified as a tumor suppressor, is inactivated by mutations in several neoplasias, including brain, breast, and prostate cancers. CDC25A and CDC25B are potential oncogenes. Overexpression of PRL-1 and PRL-2 results in cellular transformation and PRL-3 is implicated as a metastasis factor in colorectal cancer. PTP1B is a primary target for therapeutic intervention in diabetes and obesity. CD45 is a target for graft rejection and autoimmunity. Mutations in EPMA2 are responsible for a form of epilepsy, characterized by neurological degeneration and seizures.

The importance of protein phosphatases in mammalian physiology is underscored by strategies employed by several pathogens, including Yersinia, Salmonella, and vaccinia viruses, with which pathogen-encoded protein phosphatases disrupt host-signaling pathways and are essential for virulence. Systematic structural analysis of protein phosphatases provides an opportunity to make significant progress toward (1) understanding and treating the underlying mechanisms of human diseases, (2) treating a wide range of opportunistic and infectious microorganisms, and (3) generating reagents that permit experimentation to uncover new principles in cellular and molecular biology.

The protein phosphatases encompass a range of structural families, displaying various mechanisms of action and substrate specificities. The protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) represent one of the largest families in the human genome with four distinct subfamilies, including (1) the classic PTPs that recognize phosphotyrosine residues (112 human proteins), which are further divided into several subclasses of receptor-like and cytosolic PTPs, (2) the promiscuous dual-specificity phosphatases (DSPs), which recognize both phosphotyrosine and phosphoserine/phosphothreonine (33 human proteins) and include subfamiles of the phosphoinositide phosphatases (PTEN and myotubularin) and the mRNA 5’-triphosphatases (BVP and Mce1), (3) the low molecular weight phosphatases that recognize phosphotyrosine residues, and (4) the dual-specificity CDC25 phosphatases.

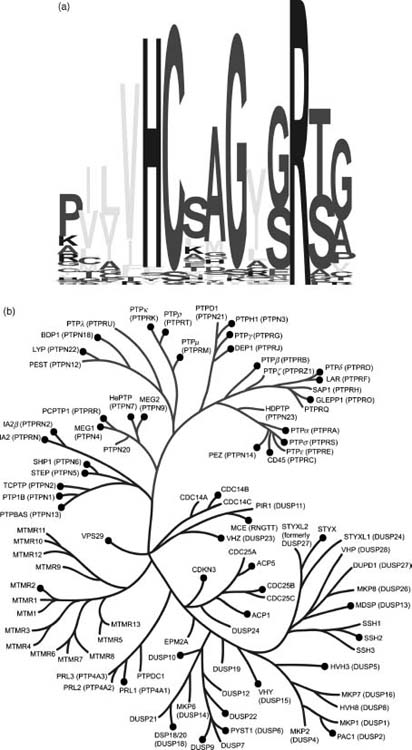

All members of the PTP family catalyze metal-independent dephosphorylation of phosphoamino acids, using a covalent phosphocysteine intermediate to facilitate hydrolysis. The amino acid sequence hallmark of the PTP family is the HCXXGXXR(S/T) motif, which contains the cysteine nucleophile. A sequence alignment showing the family conservation in the 14 amino acids surrounding this motif is shown in Figure 40.1a. It is remarkable that this active site feature represents the only amino acid sequence motif common to all PTP subfamily members.

The serine/threonine protein phosphatases are represented by two families that are distinguished by sequence homology and catalytic metal ion dependence. The PPP family members are Zn/Fe-dependent enzymes, including PP1, PP2A, and PP2B (calcineurin) (~ 15 human proteins). The PPM or PP2C-like family members are Mn/Mg-dependent enzymes (~16 human proteins). Despite sharing essentially no sequence similarity, members of both families utilize catalytic mechanisms involving a water nucleophile activated by a binuclear metal center (McCluskey, Sim, and Sakoff, 2002). The haloacid dehalogenase (HAD) superfamily contains a large number of magnesium-dependent phosphohydrolases, which operate through a covalent phosphoaspartic acid intermediate. Recently, a small number of HAD family members have been demonstrated to be protein phosphatases and have been implicated in a range of biological processes (Peisach et al., 2004; Meinhart et al., 2005; Wiggan, Bernstein, and Bamburg, 2005; Jemc and Rebay, 2007).

Figure 40.1. Human phosphatome phylogenetic tree. (a) Sequence logo (Schneider and Stephens, 1990) depicting the conservation of active site residues in the protein tyrosine and dualspecificity phosphatases. (b) Dendrogram of protein tyrosine and dual-specificity phosphatases based on variation in the active site motif. (c) Dendrogramof all other human protein phosphatases based on alignment of the entire catalytic domain. Phosphatases with structures in the PDB are indicated by black circles.

Dendrograms encompassing most of the known human phosphatases are shown in Figure 40.1 (experimental 3D public domain structures are denoted therein with black circles). The active site motif (Figure 40.1a) was used to construct the PTP/DSP tree (Figure 40.1b), whereas a multiple sequence alignment of the catalytic domain sequences was used to characterize homology between the remaining phosphatases (e.g., PPM and PPP families; Figure 40.1c). There are over 225 mammalian phosphatase structures in the PDB, providing coverage with either an experimental structure or a high-quality homology model for at least 64 human phosphatases (or ~45% of the human phosphatome). Some human phosphatases have many structural representatives, such as PTP1B with over 90 structures, whereas many others have at most a single structure in the public domain.

BIOMEDICAL THEME TARGETS: SELECTION AND PROGRESS

After the start of PSI-II, the NYSGXRC established a target list of human protein phosphatases for which there was no representative in the PDB. In addition, we selected structurally uncharacterized protein phosphatases from a number of pathogens for which sequence information was available. The coding sequences of most human phosphatases were cloned from cDNA libraries, some were purchased and ~15 were synthesized. All pathogen phosphatases were codon-optimized and synthesized (Codon Devices, Inc., Cambridge, MA).

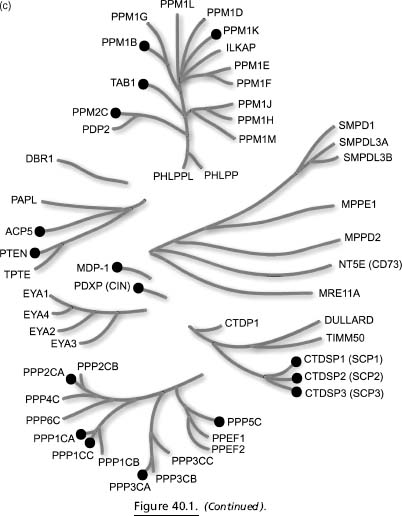

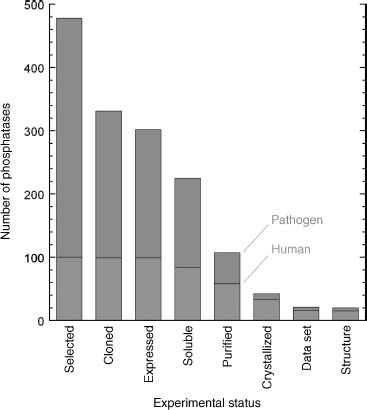

Our overall progress in this endeavor is shown in Figure 40.2 (effective October 1, 2007), wherein the number of distinct phosphatases that have progressed to each experimental stage is shown. We have observed greater attrition for the pathogen phosphatases, due in part, we believe, to the fact that many of the sequences are gene predictions that have not been experimentally verified. To compare our work on the human versus pathogen proteins, of the 58 human/mouse proteins that we successfully purified, 15 yielded structures, whereas of the 49 purified pathogen phosphatases only 5 have yielded structures.

Work on the first group of 93 pathogen phosphatases began at the end of 2005 (A. gambiae, T. gondii, and Plasmodium falciparum). In early 2007, work on an additional ~170 pathogen phosphatases was initiated, with targets selected from Candida albicans, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, Filobasidiella neoformans, Gibberella zeae, Cryptosporidium parvum, Fusarium graminearum, Trichomonas vaginalis, T. brucei, Aspergillus nidulans, Cryptococcus neoformans, Entamoeba histolytica, and Giardia lamblia.

Two years after the start of PSI-II, we have produced viable expression vectors for 304 phosphatases, and purified crystallization-grade protein for 107 of these NYSGXRC Biomedical Theme targets. We have deposited 24 X-ray crystal structures of 21 distinct protein phosphatases into the PDB (Table 40.2). Other structural biology groups and structural genomics centers have also determined significant numbers of protein phospha-tase structures. Among the most productive are the SGC (Structural Genomics Consortium; http://www.sgc.utoronto.ca) and KRIBB (Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology; https://www.kribb.re.kr/eng/index.asp), which have deposited structures of at least 19 and 7 distinct human phosphatases, respectively, within the past 2 years. There is relatively little overlap among newly deposited structures from competing consortia.

Figure 40.2. Progress on protein phosphatase structural studies. Number of protein phosphatase targets at each experimental stage of the NYSGXRC structural genomics pipeline. Human phosphatases (or mammalian orthologs) are shown in the lower part of the bars and pathogen phosphatases are shown in the upper part.

To help minimize structure overlap among research groups, the NYSGXRC publishes its target list in the TargetDB database (http://targetdb.pdb.org/) on a weekly basis, which also provides an experimental status for each target. We compare all of our targets against the contents of the PDB on a weekly basis and typically stop work on those that have been deposited by other groups. We publish experimental protocols for every attempt on every target in the PepcDB database (http://pepcdb.pdb.org/); this information includes not only detailed general protocols but also information about each clone (DNA sequence and predicted protein sequence, mutations, whether it has been codon-optimized, and small scale expression/solubility results), fermentation (media, volume, induction time and temperature, and resulting pellet weight), protein purification (yield, concentration), purified protein quality as judged by mass spectrometry (pass/fail, exact molecular weight), and crystallization conditions. We encourage this level of transparency for all structural genomics centers, particularly for target selection. Moreover, we make all of our reagents, such as expression clones, freely available. Starting in 2008, we anticipate that all NYSGXRC expression clones will be distributed by the centralized PSI Materials Repository, located within the Harvard Institute of Proteomics (HIP; http://www.hip.harvard.edu/).

BIOMEDICAL THEME TARGETS: SELECTED EXAMPLES

The NYSGXRC Biomedical Theme project has yielded a number of important structures, which have already provided unique insights into a wide range ofbiological processes with direct relevance to human disease. Illustrative examples are highlighted below.

PROTEIN TYROSINE PHOSPHATASE (PTPσ)

The 21 human receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases share a common organization with extracellular ligand binding domains, a single transmembrane segment, and intracellular phosphatase catalytic domains that function in concert to regulate signaling through ligand-mediated tyrosine dephosphorylation. Twelve of these receptor PTPs possess two tandem phosphatase domains with a catalytically active membrane proximal domain (D1) and a membrane distal domain (D2) that is thought to be inactive in most family members. PTPσ belongs to the type 2A subfamily, which possess extracellular ligand binding domains composed of 3 immunoglobulin-like (Ig) domains and 4-9 fibronectin type III-like (FNIII) domains (Pulido et al., 1995; Chagnon, Uetani, and Tremblay, 2004; Tonks, 2006). Additional members of this subfamily include the human leukocyte common antigen-related PTP (LAR) and PTP-delta (PTPδ) and the invertebrate orthologs Dlar and DPTP69D in Drosophila, PTP-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans, and HmLAR1 and HmLAR2 in Hirudo medicinalis. Expression of human receptor PTPs has been detected in all tissues examined, with the majority of PTPσ and PTPδ expression found in the brain (Pulido et al., 1995).

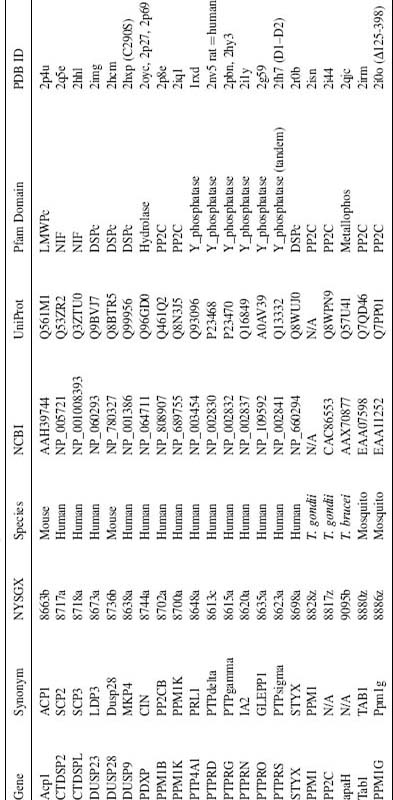

TABLE 40.2. NYSGXRC Protein Phosphatase Structures

PTPσ and other members of the type 2A subfamily play roles in regulating the central and peripheral nervous systems by providing and responding to cues for axon growth and guidance, synaptic function, and nerve repair. These complex functions appear to utilize cell-autonomous and noncell-autonomous mechanisms, involving signals originating from both the cytoplasmic phosphatase domains and the ligand binding properties of the ectodomain (Siu, Fladd, and Rotin, 2007). Using brain lysates from PTPσ-deficient mice, in combination with substrate trapping experiments, N-cadherin and β-catenin were identified as substrates of PTPσ (Siu, Fladd, and Rotin, 2007). These findings led to a model of PTPσ-regulated axon growth involving a cadherin/catenin-dependent pathway. In this model, PTPσ directs the dephosphorylation of N-cadherin, which allows the recruitment of β -catenin. In addition, PTPσ-mediated dephosphorylatin of β-catenin permits subsequent linkage to the actin cytoskeleton, resulting in increased adhesion and reduced axon growth. In PTPo-deficient mice, the resulting hyperphosphorylation of N-cadherin and β -catenin prevents the linkage between the cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane, resulting in reduced adhesion and enhanced axon growth. Further support for this model is provided by observations that dorsal root ganglion axon growth is accelerated in PTPσ-deficient mice. Of particular note is the enhanced rate of nerve regeneration after trauma (e.g., crush or transection) in PTPσ-deficient mice (Sapieha et al., 2005). In addition to enhanced rates of regeneration, PTPσ-deficient mice show an increased rate of errors in directional nerve growth, suggesting a role in both growth rates and the directional persistence or guidance of advancing neurons. The PTPσ ectodomain has been implicated in noncell-autonomous functions related to both optimal growth and guidance in regenerating neurons. These contributions to axon growth and regeneration make PTPσ an interesting potential target for therapeutic intervention.

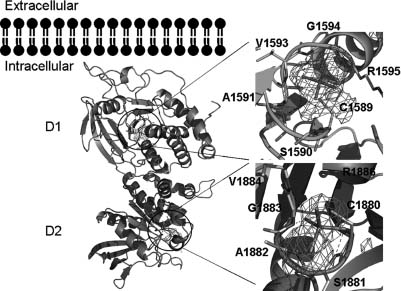

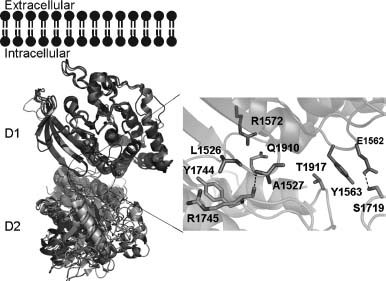

We have determined the structure of the tandem phosphatase domains of human PTPσ (PTPσ-D1-D2; PDB ID: 2FH7) (Figure 40.3). As observed in the structures ofthe LAR and CD45 tandem phosphatases, the D1 and D2 domains of PTPσ are very similar (root mean square deviation or RMSD ~1.0Å ) (Nam et al., 1999; Nam et al., 2005). The overall organization of the PTPσtandem phosphatase domains is very similar to that observed in CD45, LAR, and PTPγ. This similarity is best appreciated by superimposing the D1 domain and examining the distribution of D2 positions (Figure 40.4). The relative domain organization is dictated by residues contributing to the D1-D2 interface, which are highly conserved among PTPσ, LAR, and PTPγ.

Defining the oligomeric state of the receptor PTPs is central to understanding ligand binding, activation, and underlying regulatory mechanisms. PTPσ-D1-D2 is a monomer in the crystalline state and also behaves as a monomer in solution as judged by analytical gel filtration chromatography (unpublished data). It is remarkable that PTPα and CD45 have been reported to be negatively regulated by homodimerization (Jiang et al., 1999; Tertoolen et al., 2001; Xu and Weiss, 2002), although this observation remains an area of intense scrutiny and some controversy (Nam et al., 1999; Nam et al., 2005). Recently, it has been suggested that PTPσ forms homodimers in the cell and that dimerization is required for ligand binding (Lee et al., 2007). The apparent discrepancy between these cell-based results and our biophysical studies may be resolved by demonstrations that dimerization depends, at least in part, on interactions involving the transmembrane segment (Lee et al., 2007), which is absent from the D1-D2 construct used for our crystallographic and biophysical studies.

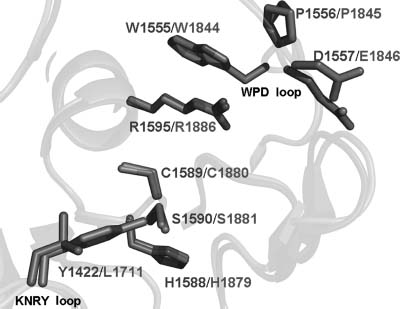

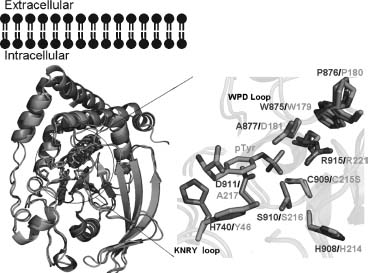

Both phosphatase domains in PTPσ possess the characteristic CX5R catalytic site motif and are capable of binding the phosphate analogue tungstate (Figure 40.3). However, as observed in most other receptor tyrosine phosphatases, the D2 domain of PTPσ appears to be catalytically inactive (Wallace et al., 1998). All catalytically active D1 domains possess WPD and KNRY loops, which contain the catalytic acid (Asp) and participate in phos-photyrosine recognition, respectively. The lack of activity in the PTPσ D2 domain is almost certainly due, at least in part, to the replacement of the WPD Asp with Glu and the KNRY Tyr with Leu (Figure 40.5). Analogous differences are present in the catalytically defective D2 domains of LAR and PTPα (Buist et al., 1999; Nam et al., 1999), and restoration ofthe WPD and KNRY sequences in these domains results in a substantial enhancement of catalytic activity. The D2 domain is thought to play an important regulatory role as intermolecular and intramolecular binding interactions between D1 and D2 domains from the same and heterologous PTPs have been shown to modulate the catalytic activity of D1 (Wallace et al., 1998; Jiang et al., 1999; Blanchetot and den Hertog, 2000; Blanchetot et al., 2002).

Figure 40.3. Structure of the human PTPs tandem phosphatase domains. The structure of the PTPs tandem phosphatase domains D1 and D2 is shown as a ribbon diagram with bound tungstate ions as stick and overlapping anomalous difference electron density in red. Domain D1 is shown in dark green and D2 in magenta. Interactions with the tungstate ion in the D1 and D2 active sites are magnified with hydrogen bonds represented as black dashes. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

Figure 40.4. Structural comparison of tandem phosphatase domains of RPTPs. Superpositions of the structures of the tandem phosphatase domains of PTPσ (green), LAR (purple), CD45 (blue), and PTPγ (orange). Amino acids involved in interdomain interactions for PTPs are shown to the right of theD1–D2 structures. For all structures, the D1and D2 domains are shown in dark and light shades of color, respectively. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

Figure 40.5. Comparison of the PTPσ D1 and D2 domain active sites. Superposition of the PTPσ D1 (green) and D2 (magenta) domain active sites. Active site residues and residues making up the WPD and KNRY loops are shown as stick figures. Root mean square deviation of D1/D2 superposition for 254 structurally equivalent Cα atoms is -1.0 Å . Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

INSULINOMA-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 2 (IA-2)

Insulinoma-associated protein 2 (IA-2) is a member of the receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase family (Lan et al., 1994). It is enriched in the secretory granules of neuroendocrine cells, including pancreatic islet β cells, peptidergic neurons, pituitary cells, and adrenal chromaffin cells (Solimena et al., 1996). The IA-2 protein is predicted to have a lumenal domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail containing a protein tyrosine phosphatase-like domain. However, enzymatic activity has not been demonstrated for IA-2, and several substitutions within the phosphatase-like domain appear to be responsible for its apparent inactivity against various substrates (Magistrelli, Toma, and Isacchi, 1996). Despite its apparent lack of phosphatase activity, the localization of IA-2 to the membrane of insulin secretory granules suggests that it may be involved in granule trafficking and/or maturation. Indeed, IA-2-deficient mice exhibit defects in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Saeki et al., 2002).

IA-2 represents a major autoantigen in type 1 diabetes, with greater than 50% of patients demonstrating circulating antibodies to the protein (Lampasona et al., 1996; Lan et al., 1996). Processing of the ~100kD IA-2 protein involves proteolytic cleavage within the lumenal domain, resulting in a ~64 kD mature form that is immunoprecipitated by insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in patient sera (Xie et al., 1998). Autoantibodies to IA-2 can also be detected during the prediabetic period. Measurement of autoantibodies to IA-2, insulin, and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65) enables prediction of type 1 diabetes in at-risk individuals, with the presence of two or more reactivities being highly predictive of future disease (Verge et al., 1996). The humoral immune response in diabetes is primarily directed against conformational epitopes located within the cytoplasmic portion of the protein (Lampasona et al., 1996; Xie et al., 1997; Zhang, Lan, and Notkins, 1997). Distinct B cell epitopes are contained within polypeptide chain segments 605-620,605-682,687-979, and 777-937 (Lampasona et al., 1996). As recently reviewed (DiLorenzo, Peakman, and Roep, 2007), type 1 diabetes patients and at-risk individuals also exhibit CD4+ T cell responses to IA-2 peptides derived from these regions of the protein. CD8 + T cells specific for IA-2 have also recently been reported in type 1 diabetes patients (Ouyang et al., 2006).

We have determined the structure of the IA-2 phosphatase-like domain (PDB ID: 2I1Y), which reveals a classic protein tyrosine phosphatase fold that is most similar to PTP1B (RMSD ~ 1.4 Å ; Figure 40.6). This protein also possesses residues that explain lack of enzymatic activity. Although the CX5R sequence is present, several other critical residues are absent, including the catalytic acid (D) in the WPD loop and a major determinant (Y) in the phosphotyrosine-recognition loop. Lack of enzyme activity is thought to be essential for the biological function of IA-2, as it can heterodimerize with both PTPα and PTPγ and down regulate PTPa (Gross et al., 2002). Our structure is particularly noteworthy for defining the relationship between the B cell and T cell epitopes, and thereby providing insights into the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. We suggest that T cell response development is facilitated by antibodies to IA-2. The presence of surface antibody would allow B cells tocapturefragments of the protein and present IA-2-derived peptides on MHC molecules for recognition by Tcells (KeandKapp, 1996). Antibody-bound protein fragments could also be directed to antigen-presenting cells via Fc receptors, a targeting that allows antigens to be efficiently processed and presented to T cells (Villinger et al., 2003). A bound antibody can also modulate processing of T cell determinants, suppressing the presentation of some epitopes and enhancing the generation of others, thus influencing the process of epitope spreading (Davidson and Watts, 1989; Watts and Lanzavecchia, 1993; Simitseketal., 1995).

Figure 40.6. Comparison of the structures of IA-2 and PTP 1B. Superposition of the structures of IA2 (green) and PTP1B (cyan), with active site residues shown as stick figures. Active site residues of IA2 and PTP1B bound to phosphotyrosine are magnified, highlighting differences responsible for the lack of catalytic activity of IA-2. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

SMALL C-TERMINAL DOMAIN PHOSPHATASE 3

The small C-terminal domain phosphatases (SCP) comprise a family of Ser/Thr-specific phosphatases that play a central role in mRNA biogenesis via regulation of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II). RNAP II is a large, multisubunit enzyme containing 12 components (Sayre, Tschochner, and Kornberg, 1992), the largest of which bears a unique C-terminal domain (CTD) that is flexibly linked to a region of the macromolecular machine near the RNA exit pore. The CTD consists of multiple repeats of the consensus sequence Tyr1-Ser2-Pro3-Thr4-Ser5-Pro6-Ser7 (Corden et al., 1985), with the number of repeats varying among different organisms (e.g., 26 are found in yeast versus 52 in human). Reversible phosphorylation of the CTD plays a crucial role in RNAP II progression through the transcription cycle, controlling both transcriptional initiation and elongation (Goodrich and Tjian, 1994; Dahmus, 1996). The CTD phosphorylation status also affects RNA processing events, such as 5’-capping and 3’-processing (Ho and Shuman, 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2000; Shatkin and Manley, 2000; Ahn, Kim, and Buratowski, 2004). The CTD of RNAP II is predominantly phosphorylated at Ser2 and Ser5 within the heptapeptide repeats by members of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) family (e.g., CDK7, CDK8, and CDK9) (Hengartner et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2000). Members of the SCP family work in opposition to restore the unphosphorylated state. It is remarkable that SCP family members also modulate the function of SMAD transcriptional regulators by dephosphorylating residues within the C-terminus and the linker region between the two conserved domains of SMAD (Knockaert et al., 2006; Sapkota et al., 2006).

Given their roles in transcriptional regulation, SCP family phosphatases have been implicated in a wide range of physiologic and pathologic processes. SCP3 has been identified as a tumor suppressor. The SCP3 gene is frequently (>90%) deleted or its expression is drastically reduced in lung and other major human carcinomas (Kashuba et al., 2004). In contrast, a related family member, SCP2, was initially identified in a genomic region frequently amplified in sarcomas and brain tumors (Su et al., 1997). Members of the SCP family act as evolutionarily conserved transcriptional regulators that globally silence neuronal genes (Yeo et al., 2005). SCP2 interacts with the androgen receptor (AR) and appears to control promoter activity via RNAP II clearance during steroid-responsive transcriptional events (Thompson et al., 2006). FCP1, the first SCP related protein to be identified, interacts directly with HIV-1 TAT through its noncatalytic domain and is essential for TAT-mediated transcriptional transactivation (Abbott et al., 2005).

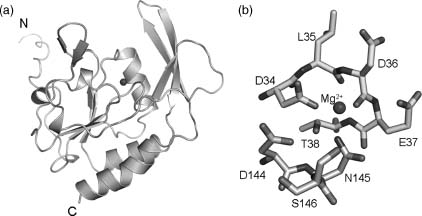

To date, the structures of three SCP family members have been determined, including the NYSGXRC structures of SCP2 (PDB ID: 2Q5E) and SCP3 (PDB ID: 2HHL). SCP3 is monomeric both in solution and the crystalline state, and shares high sequence identity(-83%) and significant structural similarity (RMSD ~0.6 Å ) with both SCP1 (PDB ID: 2GHQ) (Kamenski et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2006) and SCP2. These proteins belong to the HAD superfamily, which encompasses a large number of magnesium-dependent phospho-hydrolases characterized by the presence of a conserved DXDX motif (Figure 40.7). This signature sequence contributes to the catalytic site and is responsible for coordination of the catalytically essential magnesium cation, with the first aspartic acid serving as the nucleo-phile and phoshoryl acceptor (Kamenski et al., 2004). Most HAD family members catalyze phosphoryl transfer reactions involving small-molecule metabolites (e.g., phosphoserine). Structures of two HAD protein serine phosphatases from human (PDB ID: 1L8L) (Kim et al., 2002) and Methanococcus jannaschii (PDB ID: 1F5S) (Wang et al., 2001) have also been determined by others. Despite rather low sequence identity between the SCPs and small-molecule phosphatases (14% between 2HHL and 1F5S; RMSD —2.7 Å ), they share significant similarities in overall topology and active site architecture (Figure 40.8).

Figure 40.7. Structure of SCP3. (a) Ribbon diagram of SCP3 showing the DXDX catalytic loop (yellow) and the catalytic Mg2+ ion modeled from SCP1 (magenta). (b) Atomic details of the SCP3 catalytic site, again with the Mg2+ ion modeled from SCP1. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

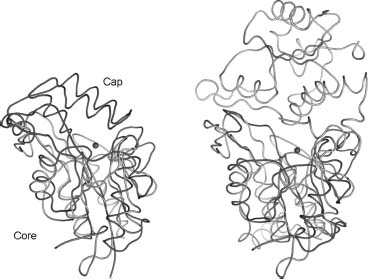

SCP1, SCP2, and SCP3 are composed of a central five-stranded parallel β -sheet flanked by three α-helices on one side and a substantial loop-containing segment on the opposite face. An additional antiparallel three-stranded β-sheet is formed within the extended loop connecting β -strands 2 and 3 of the central β -sheet. In contrast, the M. jannaschii phosphoserine phosphatase (PDB ID: 1F5S) contains both the core domain and a capping domain that impinges on the active site. In the case of the tetrameric Haemophilus influenzae deoxy-D-mannose-octulosonate 8-phosphatase (PDB IDs: 1K1E and 1J8D), an adjacent monomer packs on top of the core domain and serves as the “cap” (Figure 40.8).

As previously discussed by Allen, Dunaway-Mariano, and colleagues (Peisach et al., 2004), the overall architecture of these active sites appear to be related to the type of substrate recognized. For example, the phosphoserine phosphatases, which recognize small molecules, typically possess small catalytic sites that are relatively sequestered from solvent. Such sequestration is generally provided by an additional “capping” domain present in the structure or by the formation of a higher order oligomeric species that occludes the catalytic site. In contrast, the SCP catalytic sites, which recognize CTD heptad repeats are larger and more accessible to solvent. This architectural variation may be of wider import. For example, in MDP-1, another putative HAD superfamily protein phosphatase thatdephosphorylates phosphotyrosine (Peisach et al., 2004), the catalytic site also appears to be highly solvent accessible. Recently published work suggests that MDP-1 might recognize posttranslationally encoded protein sugar phosphates, which would also require a substantially more solvent accessible catalytic site (Fortpied et al., 2006). This architectural type is also present in the phosphatase domain of T4 polynucleotide kinase, a HAD superfamily member that utilizes polynucleotides substrates (Galburt et al., 2002). It is remarkable that all of these HAD phosphatases recognize their polymeric substrates and perform catalysis at sites present at termini or linker regions. It, therefore, appears that a combination of catalytic site accessibility and substrate dynamics is required to support the biological activity of these polymer substrate specific phosphatases.

Figure 40.8. Structural comparisons of SCP3. (a) Superposition of SCP3 (green) with Methanococcus jannaschii phosphoserine phosphatase (red, PDB ID: 1F5S). The SCP3 catalytic site is freely accessible to solvent, whereas the alpha-helical capping domain in phosphoserine phosphatase shields its active site. (b) Superposition of SCP3 (green) with a dimer of the tetrameric Haemophilus influenzae deoxy-D-mannose-oculosonate 8-phosphatase (red and gray, PDB ID: 1K1E). Mg2+ ions are shown as pink spheres, and conserved phosphate-binding loops are shown in yellow. The capping domain of 1F5S occludes the active site entrance. In 1K1E, the second subunit of the dimmer plays a similar role. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

CHRONOPHIN

Chronophin is an example of the burgeoning family of “moonlighting” proteins (Jeffery, 1999; Jeffery, 2003), as it plays a central role in vitamin B6 metabolism and serves as a major regulator of the actin cytoskeleton (Wiggan, Bernstein, and Bamburg, 2005). This protein was first identified as pyridoxal phosphatase, which specifically dephosphorylates pyridoxal 5’-phopshate (PLP), the coenzymatically active form of vitamin B6 that participates in a remarkable range of enzymatic transformations (Fonda, 1992). PLP synthesis requires a flavin mononucleotide-dependent pyridoxine 5’-phosphate (PNP) oxidase and an ATP-dependent pyridoxal kinase. Degradative pathways for PLP include the action of one or more pyridoxal phosphatases. The overall mechanism by which PLP levels are regulated is complex to say the least and includes PLP biosynthetic and degradative pathways, PLP binding proteins, and proteins that regulate availability and/or transport of synthetic precursors. Given its central role in PLP metabolism, it is not surprising that the PLP phosphatase is expressed in all human tissues examined and is particularly abundant in brain, suggesting a specialized role in the central nervous system (CNS) (Jang et al., 2003).

More recently, Bokoch and colleagues demonstrated that chronophin plays a direct role in regulating the actin cytoskeleton (Gohla, Birkenfield, and Bokoch, 2004) (Figure 40.9). Under physiologic conditions, monomeric actin (G-actin) spontaneously polymerizes to form actin filaments (F-actin) with chemically and structurally distinct ends, termed barbed and pointed (Pollard and Cooper, 1986, Schafer and Cooper, 1995). Further assembly of F-actin into an array of higher order assemblies underpins all actin-based dynamic processes, including cell motility, vesicle movement, and cytokinesis. In vivo, actin polymerization is dominated by monomer addition to barbed ends, making barbed end generation a central focus in studies of dynamic actin-based processes (Schafer and Cooper, 1995; Zig-mond, 1996). Cofilin is a 15 kD protein that severs the actin filament by disrupting the noncovalent bonds between monomers comprising the filament (Ono, 2007). Filament severing increases the number of polymerisation-competent barbed ends, and results in increased rates of actin polymerization. Cofilin is also thought to be involved in depolymerization, because under certain conditions cofilin not only increases the number of filaments, but can also increase the rate of monomer dissociation from the newly created pointed ends (Ono, 2007). Cofilin itself is regulated by a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle: LIM kinase-mediated phosphorylation of Ser3 inactivates cofilin (Scott and Olson, 2007) while the action of the slingshot phosphatases return cofilin to the active state (Huang, DerMardirossian, and Bokoch, 2006 Ono, 2007). Bokoch’s work exploited a wide range of techniques to demonstrate chronophin specificity. siRNA knockdowns of chronophin activity (reduced phosphatase activity) increases phosphocofilin levels, while overexpression of chronophin decreases phosphocofilin levels. Decreased chronophin activity also results in stabilization of F-actin structures in vivo and causes massive defects in cell division (Gohla, Birkenfield, and Bokoch, 2004).

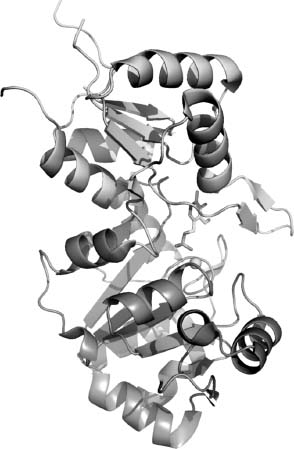

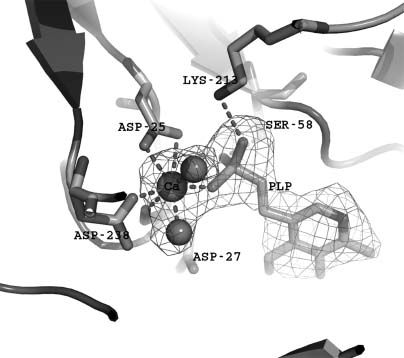

The NYSGXRC structure of human chronophin (PDB ID: 2OYC) confirmed that this protein is indeed a member of the HAD phosphatase family. It possesses a typical core domain that contains the catalytic signature sequence DXDX. There is also a very substantialcapping domain that abuts the catalytic site (Figure 40.10). The structure of the PLP-bound form of the enzyme was obtained by substituting Mg2 +(PDB ID: 2P27) with the catalytically inert Ca2 + (PDB ID: 2P69). This substitution results in a change of metal ligation from six to seven coordinate via bidentate coordination of the catalytic aspartic acid (Asp25), which results in the near-complete loss of activity (Figure 40.11). Our structure demonstrates that bound PLP is largely buried, with the phosphate being completely shielded from solvent (Figures 40.10 and 40.12). Immediately after our first structure was deposited, three chronophin structures from Kang and coworkers were released from the PDB (PDB IDs: 2CFR, 2CFS, and 2CFT).

Figure 40.9. Cofilin-mediated F-actin severing. F-actin severing activity of cofilin is regulated by a phosphorylation cycle involving the LIM kinase and the slingshot and chronophin phosphatases. Actin monomers are represented by ellipses.

Figure 40.10. Chronophin structure. Ribbon representation of chronophin/PLP phosphorylase with bound PLP and Ca2+. The core domain is the lower half, the capping domain is the upper half, PLP isshown with stick representation, andthe Ca2+ isshown as a sphere. The catalytic site lies at the interface between the core and capping domains.

Demonstration of cofilin phosphatase activity is remarkable given the structural and functional features associated with all previously characterized polymer-specific HAD family phosphatases. As noted above, two members of the SCP family, MDP-1 and T4 polynucleotide kinase, all lack a capping domain, resulting in a relatively open and solvent-accessible active site. In contrast, chronophin appears unique among the polymer-directed HAD phosphatases examined to date, because the presence ofa substantial capping domain largely occludes the catalytic center (Figures 40.12 and 40.13). Analysis of our chronophin structure suggests that conformational reorganization of the core and capping domains is required to facilitate binding of the phosphorylated N-terminus of cofilin. The N-terminus of cofilin is unstructured in solution (Blanchoin et al., 2000; Pope et al., 2004) and, like the dynamic properties described above for other HAD-associated polymeric substrates, this behavior is almost certainly essential for it to gain access to the chronophin catalytic site. It, therefore, appears that the HAD family has evolved various mechanisms by which to perform chemistry on polymeric substrates. Availability of our structures and protein reagents provides the necessary foundation for a detailed study of chronophin function. These results will be particularly relevant to our fundamental understanding of cancer, as the phosphorylation status of cofilin is directly implicated in the actin-based mechanisms underlying invasion, intravasation, and metastasis of mammary tumors (Wang et al., 2006).

Figure 40.11. Chronophin catalytic site. The active site of chronophin with its ligand PLP and inhibitory Ca2+. The Ca2+ (green sphere) is hepta-coordinated and participates in a bidentate interaction with the active site nucleophile Asp-25. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

Figure 40.12. Chronophin capping domain. Superposition of chronophin and SCP (CTD phosphatase) (PDB ID: 2HHL), which lacks a capping domain. The core domains share 11% sequence identity and super impose with a DALI Z score of 6.6 and an RMSD of-2.9Å -for 116 structurally equivalent Ca atoms.

Figure 40.13. Inaccessibility of PLP in the chronophin catalytic site. Surface representation of chronophin (dark grey) with bound ligand PLP (light grey) in the same orientation as shown in Figure 40.12. The PLP is viewed ontheedgeandthe phosphoryl group is completely buried from solvent.

OTHER PHOSPHATASES

In addition to the human phosphatase structures described above, the NYSGXRC has determined and made publicly available X-ray structures from T. gondii (PDB IDs: 2I44 and 2ISN), mosquito (TAB1, PDB ID: 2IRM; and PPM1G, PDB ID: 2I0O), and T. brucei (PDB ID: 2QJC), which will be described elsewhere.

BIOMEDICAL THEME TARGETS: POTENTIAL IMPACT ON DRUG DISCOVERY

As highlighted by some of the examples described in detail above, systematic structural characterization of the protein phosphatases provides significant mechanistic and functional insights. Notwithstanding these and other successes, we believe that full exploitation of the growing structural phosphatome database must include efforts to discover new therapeutic phosphatase inhibitors and generate reagents that allow specific inhibition of signaling pathways in cell culture and whole animal model systems. There is much interest in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries in protein phos-phatases as drug discovery targets, as evidenced by recent publications on PTP1B and related targets (reviewed in Pei et al., 2004). We briefly highlight in the following sections two structure-based approaches to the problem of discovering potent phospha-tase inhibitors from academe.

FRAGMENT CONDENSATION LEAD DISCOVERY STRATEGY APPLIED TO PTP1B

The concept of inhibitor (or agonist) design via condensation of individual small-molecule fragments known to bind proximally in the vicinity of a target protein active site has received growing attention over the past decade (Hajduk and Greer, 2007). The simple rationale is that the geometrically appropriate covalent linkage of multiple low affinity fragments/functionalities will generate high-affinity species. A rigorous thermodynamic treatment of this phenomenon was published by Jencks as early as 1981 (Jencks, 1981) and demonstrated that the enhanced affinities of the final species is the consequence of both the additivity of the intrinsic binding energies (ΔG) of the individual fragments.

Fragment libraries are typically composed of 1000-10,000 low molecular weight compounds representing a breadth of chemically diverse substructures that possess various chemical functional groups, which can facilitate either target binding or further chemical elaboration. Selection for solubility, lipophilicity, H-bonding donors/acceptors, and known toxicity or ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) properties are typical considerations in building the library.

Various approaches to fragment binding detection have been adopted, among them are mass spectrometry (Erlanson, Wells, and Braisted, 2004), NMR (Shuker et al., 1996; Baurin et al., 2004), crystallography (Blaney, Nienaber, and Burley, 2006; Mooij et al., 2006) and combinations therefrom (Moy et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2003). Special considerations for fragment-based discovery using X-ray crystallography include the necessity for obtaining a well-characterized crystal form of the target protein that diffracts well (dmin < 2.5 Å ), possesses a lattice amenable to soaking experiments (i.e., without occlusion of the target site), and is able to withstand exposure to modest quantities of organic solvents (e.g., ethanol and DMSO are popular solvents for chemical fragments). Initial crystal soaking experiments can be conducted on mixtures of the library to speed the initial screening with follow-up soaks using individual fragments, where an individual component cannot be conclusively identified from the resulting electron density maps.

There are numerous examples in the literature of the success of this method, many coming from small biotechnology companies. Hartshorn et al. (2005) have published a summary of their initial findings on five very different targets (p38 MAP kinase, CDK2, thrombin, ribonuclease A, and PTP1B). A detailed summary of a similar approach applied to spleen tyrosine kinase has been published by Blaney, Nienaber, and Burley (2006). The power of the method is highlighted by the following example for PTP1B, which represents the simplest possible approach to fragment screening with a screening library composed solely of phosphotyrosine.

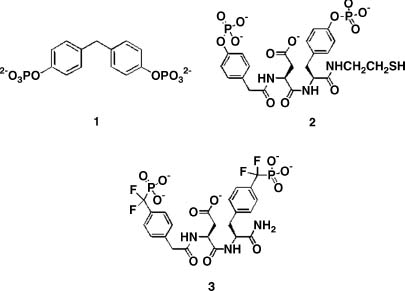

Figure 40.14. Compounds that bind PTP1B. The low Km, low kcat substrate, compound 1, compound 2; and a highly selective, nonhydrolyzable bidentate inhibitor, compound 3.

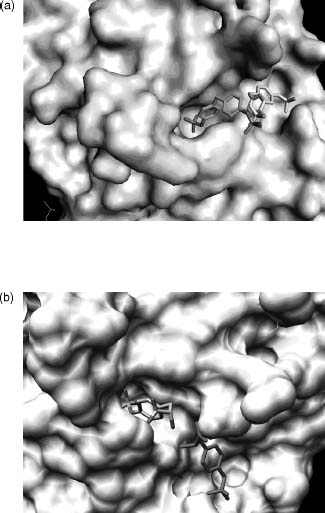

An analysis of the substrate specificity of PTP1 (the rat ortholog of human PTP1B) revealed that this enzyme catalyzes hydrolysis of a wide variety of low molecular weight phosphate monoesters. One of these substrates (compound 1; Figure 40.14) exhibits poor turnover (6.9/s) coupled with an extraordinarily low Km (16 µM) value for a nonpeptidic species. This latter property suggested that substrate may bind tightly to the enzyme in a less than optimal fashion with respect to catalysis. Crystallographic analysis of compound 1 bound to a catalytically incompetent C215S mutant form of PTP1B revealed that the substrate can occupy one of the two mutually exclusive binding modes: (1) a catalytically competent active site-bound form and (2) a nonproductive peripheral site-bound form (Figure 40.15a) (Puius et al., 1997). Furthermore, the less sterically demanding phospho-tyrosine (library of one) was observed to simultaneously bind to both sites (Figure 40.15b). Although the active site is highly conserved among all PTPase family members, the peripheral binding site is not. This latter observation suggested that a bidentate ligand, capable of occupying both positions on the surface of the phosphatase, would not only display enhanced affinity but also enhanced selectivity for PTP1B.

Based on these observations, a combinatorial library of 184 compounds was designed containing (1) a fixed phosphotyrosine moiety, (2) 8 structurally diverse aromatic acids (terminal elements) to target the unique peripheral site, and (3) 23 structurally diverse ’’linkers’’ to tether the phosphotyrosine with the array of terminal elements (Shen et al., 2001). Compound 2 was identified as the lead species from the library and the corresponding nonhydrolyzable difluorophosphonate (compound 3) was synthesized. Compound 3exhibits high affinity (Ki = 2.4 nM) and extraordinary selectivity (1000-10,000-fold versus an array of phosphatases) for PTP1B. Analogues of this compound have recently been shown to serve as insulin sensitizers and mimetics in cell culture and as appetite suppressors in animal models. These results are consistent with the role of PTP1B as a negative regulator of the insulin and leptin signaling pathways (Taylor and Hill, 2004).

Figure 40.15. Surface representation of the PTP1B active site. (a) Compound 1 binds to a catalytically incompetent form of PTP1B via one of the two mutually incompatible binding modes, which encompass either the active site (multicolor) or a secondary peripheral site (black and white). (b) Phosphotyrosine simultaneously binds to the active site (multicolor) and a secondary peripheral site (red). Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

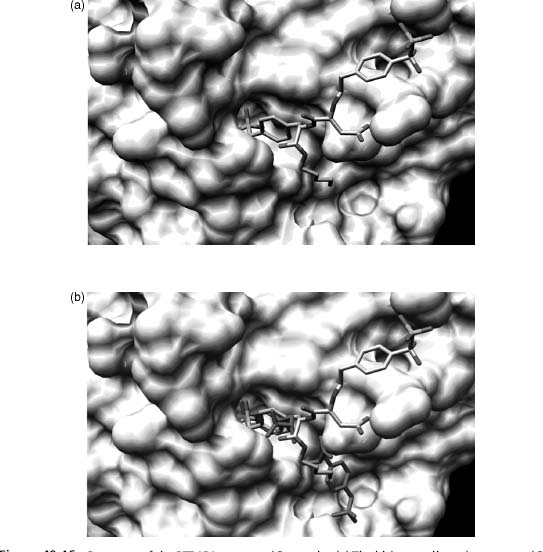

The structural biology finding that served as the source of inspiration to prepare the library of bidentate phosphatase inhibitors was based on the surprising finding that PTP1B can simultaneously bind two phosphotyrosine amino acid residues. However, Nature had an additional surprise in store with the bidentate ligand compound 3, designed to coordinate both the active and peripheral sites. Subsequent crystallographic analysis revealed that although compound 3binds to the active site in the expected fashion, it does not coordinate to the predicted peripheral site (Figure 40.16). Instead, the bisphosphonate compound 3coordinates in an unanticipated fashion to a completely different secondary site on the surface of the enzyme (Sun et al., 2003). This secondary site, however, like the initially identified peripheral site, is not conserved among PTPase family members. The latter appears to provide the structural basis for the extraordinary selectivity displayed by compound 3 and its congeners for PTP1B. This serendipitous finding was the product of structure-guided library-screening that relied on access to purified protein samples, and underscores the potential value of the PSI Materials Repository and its contents.

Figure 40.16. Structure of the PTP1B/compound 3 complex (a) The bidentate ligand, compound 3, is bound to the active site and a secondary peripheral site different from that observed with compound 1 and phosphotyrosine. (b) Overlay of the double binding mode of phosphotyrosine (red) and the bidentate ligand compound 3 (multicolor). Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

VIRTUAL SCREENING STRATEGY APPLIED TO PP2Cα

In silico virtual ligand screening (VS) uses computational approaches to identify small-molecule ligands of target macromolecules. The process can be usefully divided into two stages, including docking and scoring. Docking utilizes a structure of the macromolecular target to calculate whether or not a particular compound can fit within aputative binding cleft (e.g., enzyme active site). Scoring methods estimate the free energy of binding for a particular ligand bound to the target in a particular pose, thereby permitting prioritization of predicted target-ligand complexes according to calculated binding energy.

Compound library selection plays an importantrole in VS. In principle, vastcompound sets of diverse properties (including size, lipophilicity, and chemical substructure) are accessible to VS due to the availability of powerful computational resources. For example, Irwin and Shoichet have compiled a freely available database of ~4.6 million commercially available compounds with multiple defined subsets, useful search functions, literature references, chemical similarity cross-references, vendor information, and atomic coordinates (http://blaster.docking.org/zinc/; Irwin and Shoichet, 2005). Moreover, the National Cancer Institute maintains a repository of over 140,000 compounds together with associated literature and structural information; of these 1900 are arrayed on multiwell plates intended for use in ligand discovery (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/index.html). For a review of the growing availability of chemical databases, see Baker (2006).

While there certainly exists a benefit to having a source of the actual compound for follow-up in vitro studies, hypothetical small-molecule compounds can also be generated in silico and serve as inputs for VS calculations. In practice, electronic compound libraries are processed (Cummings, Gibbs, and DesJarlais, 2007) and filtered for a variety of properties (e.g., Lipinski’s rules) either prior to VS (forward filtering) to generate a smaller test set on which more thorough calculations can be undertaken or after VS (backward filtering) to eliminate excessive downstream chemistry on candidates with poor chemical properties (Klebe, 2006). Moreover, in contrast to fragment approaches (see above) for which very small molecules are observed to bind specifically, albeit sometimes quite weakly, to the target protein, VS methods encounter difficulty placing fragment molecules unless the binding landscape is limited to a manageably small area of the target protein surface. Thus, for VS, library components are usually larger and somewhat more elaborated compounds.

Selection of an appropriate ’’druggable’’ macromoleular target is also of critical concern. The availability of high-resolution structural data not only support VS in general, but also allow the objective assessment, selection, and accurate boundary definition of the protein surface site to be interrogated (An, Totrov, and Abagyan, 2005; Vajda and Guarnieri, 2006).

AVS campaign against a phosphatase target for which no nonphosphate-based inhibitor was known has been published recently (Rogers et al., 2006). The authors selected PP2Cα as a target due to its importance in cell cycle and stress response pathways and the availability of a crystal structure (PDB ID: 1A6Q; Das et al., 1996). While inspection of the enzyme binding site revealed three putative binding pockets, PP2Cα represents a more difficult case for VS due to the presence of two bound metal ions coordinated by six waters leading to ambiguity concerning the relevant target structure. Using AutoDock 3.0 (Morris et al., 1998), the authors ran docking and scoring calculations against control compounds (pSer, pThr, and pNPP docked readily with their phosphate groups overlaying a bound phosphate ion observed in the X-ray structure) and the NCI Diversity Set (1900 compounds). This initial screening exercise was followed by a chemical similarity search of the Open NCI Database (currently > 260,000 small-molecule structures) resulting in a second generation library, which was also docked against PP2Cα and the resulting hits scored. Additional docking calculations were run on the most attractive-looking hits against the apo form of the protein (deleting metals and waters) and all 64 possible permutations of water deletions (while retaining the active site metals). Perhaps in an indication of binding to pockets surrounding the metals, there was some agreement among the runs with metal/water deletions when compared to the original run. Postscoring filtering for solubility (compounds with clog P < 6 were retained) yielded some leads, which were then requested from the NCI for inhibition assays against PP2Cα and a panel of three additional Ser/Thr phosphatases. Additional assays of nonspecific inhibition due to aggregation by varying enzyme concentration or adding detergent were conducted. Remarkably, at compound concentrations of 100 µM, many of VS hits demonstrated robust inhibitory activity; compound 109268 showed —80% inhibition of PP2Cα and reasonable selectivity for PP2Cα and PP1 (80% inhibition) versus PP2A and PP2B (40% inhibition) with no appreciable aggregation effects. No further elaboration of these leads was described.

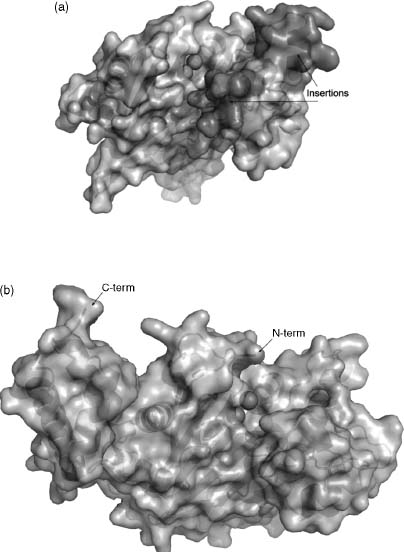

In light of this result, it is of considerable interest that the NYSGXRC has recently determined the structure of a human PP2Cβ (PPM1B) fragment (PDB ID: 2P8E) and the T. gondii ortholog of PPM2C (PDB ID: 2I44; herein referred to as PP2Ctg). The structures of PP2Cα and PP2Cβ are nearly identical (RMSD — 0.8 A; 80% sequence identity), although the PP2Cβ expression construct did not include —90 C-terminal residues, which form a small α-helical subdomain distal to the active site in PP2Cα. The structure of Ser/Thr phosphatase PP2Ctg (Figure 40.17) resembles those of human PP2Cα (Das et al., 1996) and human PP2C( structures. Pair-wise RMSDs comparing the structure of PP2Ctg to hPP2Ca and hPP2Cβ are —1.9 A (23% sequence identity) and —1.8 A (25% sequence identity), respectively (Figure 40.18). The four-layered αββα architecture, the number of β-strands, and the location and coordination of the dimetal center are conserved among these structures. Although the core catalytic domain structure is conserved, there are significant differences between the human and the T. gondii enzymes. The a-helices in PP2Ctg are longer than those found in the human enzyme structures in one of the two α-helical layers and PP2Ctg lacks the C-terminal 3 α-helices present in the human PP2C structures. Remarkably, in the vicinity of the active site, PP2Ctg possesses two insertions (PP2Ctg residues 207-213 and 218-232) forming an α-helix and a β-sheet, which are not found in the human PP2Cs (Figures 40.18 and 40.19a). Another significant difference affecting the nature of the active site results from the disposition of the N-terminus. In both human PP2C structures, the N-terminus is close to the active site and forms an additional β-strand along one side of the β-sandwich (Figure 40.19b), whereas in PP2Ctg, the N-terminus folds down away from the metals and makes contacts on both sides of the β-sandwich. Several other residues found in the vicinity of the active site and identified as potentially important for ligand binding to human PP2Ca (Rogers et al., 2006) are not conserved: V34 → K, E35 → H, H62 → T, A63 → V, and R186 → F (using PP2Cα residue numbering). This sequence/structure divergence gives rise to significant variation in the active sites of human versus T. gondii PP2Cs (Figure 40.19a and b) and may provide the basis for discovery and development of parasite selective phospha-tase inhibitors.

Figure 40.17. X-ray structure of T. gondii PP2C (PDB ID: 2i44). Inset: two calcium ions supported by conserved aspartates and coordinated waters.

Figure 40.18. Structural alignment and overlay of PP2Cs. PP2Ctg, PP2Cα, and PP2Cβ.

BIOMEDICAL THEME TARGETS: CONCLUSION

The impact of various structural genomics efforts on our structural and functional understanding of the human protein phosphatases and protein phosphatases from a wide range of biomedically relevant pathogens is already apparent. Current coverage of the human protein phosphatome is ~45%, with the promise of many more structures to come within the next few years. These data will provide insights into both normal and pathophysiologic processes, including transcription regulation, signal transduction, neural development, and type 1 diabetes. They will also help to stimulate and support discovery of specific small-molecule inhibitors of phosphatases, for use both in biomedical research and in various clinical settings.

Figure 40.19. Surface representations of PP2Cs. (a) PP2Ctg: Ca2+ shown as green spheres; surface corresponding to amino acid insertions 207–213 and 218–232 colored orange. (b) PP2Cα in similar orientation as PP2Ctg: Mn2+ shown as green spheres. Figure also appears in the Color Figure section.

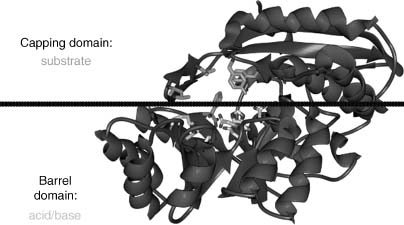

COMMUNITY-NOMINATED TARGETS: MOTIVATION

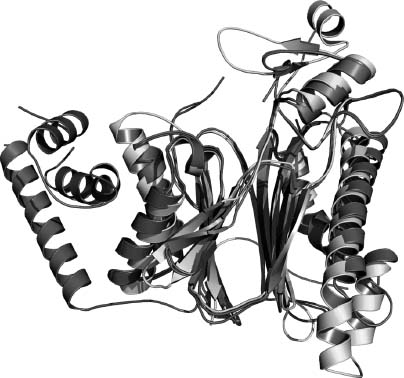

Our initial strategy for community-nominated targets was to identify multidisciplinary collaborative research programs for which determination of a large number of novel protein structures could make a material difference, as opposed to the incremental progress that might be anticipated from individual targets proposed by disparate research groups. Two members of the NYSGXRC (Almo and Sali) are also involved in a Project Program Grant (PPG) to examine the structural and chemical basis for functional evolution of the enolase and amidohydrolase metalloenzyme superfamily, in collaboration with John A. Gerlt (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign), Frank M. Raushel (Texas A&M University), Patricia C. Babbitt (UCSF), Matthew Jacobson (UCSF), and Brian Shoichet (UCSF). This highly successful program is developing an integrated sequence-structure-based strategy for functional assignment of unknown proteins by predicting the substrate specificities of unknown members of the functionally diverse AH and EN superfamilies that share the ubiquitous α8β8 barrel fold (Figure 40.20, reviewed in Gerlt and Ruashel, 2003). The PPG integrates extensive expertise in functional, structural, and computational enzymology. These diverse, complementary approaches to studies of enzyme substrate specificity should aid in deciphering the ligand binding of other functionally uncharacterized proteins. Their choice of the EN/AH superfamily was motivated by the marked segregation of amino acids contributing to acid/base catalysis (largely derived from the barrel domain) from those dictating enzyme substrate specificity (largely derived from the overlying cap domain).

COMMUNITY-NOMINATED TARGETS: SELECTION AND PROGRESS

Target selection for the EN/AH superfamily was a collaborative process overseen by Babbit (PPG) and Sali (NYSGXRC/PPG). The later stages of target selection were also extensively guided by mechanistic insights from Gerlt (PPG) and Raushel (PPG). Our joint objective was to select structure determination targets from among both known enolases and amidohy-drolases and newly identified ENs and AHs (particularly from organisms for which genomic DNA is readily available). Known and putative EN and AH sequences can be found within the PPG-curated structure-function linkage database SFLD (http://sfld.rbvi.ucsf.edu). In addition to this original set of target sequences, new EN and AH sequences were identified from the GenBank nonredundant sequence database, and 11 EN sequences with low similarity to those of known ENs were added to the NYSGXRC community target list in November 2006. Genes for these have all been synthesized and two have already yielded structures (PDB ID: 2PCE and 2PMQ).

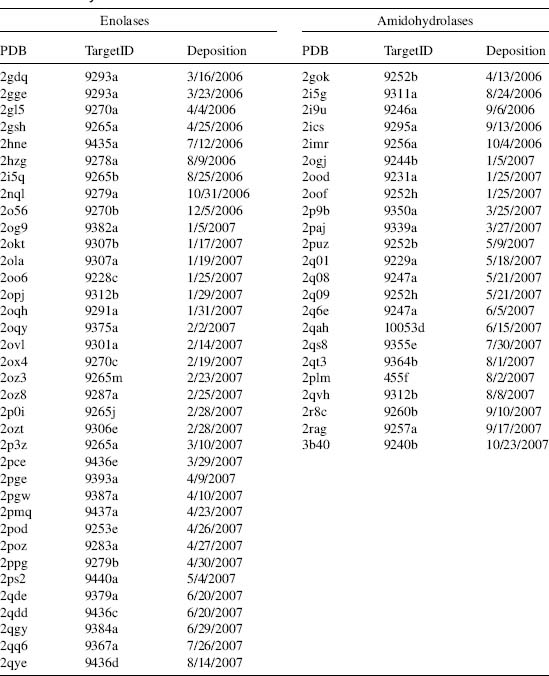

To date, we have targeted a total of 279 amidohydrolases and 214 enolases. Expression clones for 370 AH/EN targets have been generated (212 AH, 148 EN), 71% through gene synthesis. One hundred and eight amidohydrolases and sixty enolase targets have been successfully purified (58% from synthetic clones). More than 82 AH/EN targets have yielded crystals (44 AH, 38 EN), and over 850 crystals have been harvested and screened for crystal quality. Diffraction data sets for 59 distinct AH/EN targets have been collected (23 AH, 36 EN). As of October 2007, structures for 34 distinct ENs and 18 distinct AHs have been deposited into the PDB. They have been observed with Mg, Zn, Fe, or Zn bound (and, in some cases, no metal). A structure summary is provided in Table 40.3.

Success rates with the EN superfamily (57% of successfully purified proteins progressed to structures) are significantly better than those observed for the AHs (17%). Our relatively poor success with the AHs reflects our continuing challenge with a subset of the AHs for which unusually broad peaks are observed in electrospray ionization mass spectra following purification to apparent homogeneity as judged by gel electrophoresis. Denaturation of the protein and metal removal (using EDTA or 1,10-phenanthroline) had no effect on appearance of the ESI-MS peaks. Roughly 5-10% of the purified AHs exhibited ESI-MS peak broadening, which appears to be due to covalent modification of solvent-accessible residues. Five AHs were analyzed by proteolytic digestion and peptide mapping. In all cases, correct protein identity was confirmed (—80% polypeptide chain coverage). We have not yet overcome this problem, but will continue to characterize this target family with other biophysical methods and to evaluate their performance in crystallization. Only one of the purified AHs with a broad ESI-MS peak led to successful structure determination. We are also evaluating whether or not E. coli fermentation in different media or expression in insect cells may eliminate this unwanted heterogeneity.

COMMUNITY-NOMINATED TARGETS: FUNCTIONAL CHARACTERIZATION

NYSGXRC structures have already had considerable impact on the PPG. All members of the mandelate racemase subfamily of the EN superfamily that have been characterized to date contain a KXK sequence at the end of the second β-strand that is responsible for substrate recognition and chemistry. The NYSGXRC determined the first structure of a target that contains KXD at this position (PDB ID: 2GL5). This structure is now being analyzed computationally and experimentally for novel function. Moreover, our efforts have highlighted the importance of frequent communication between the NYSGXRC and the community-target nominator(s). For example, our work on a particular EN yielded a structure of the apoenzyme (PDB ID: 2GDQ), which was only of partial use to the PPG, as all members of the EN/AH superfamilies are metal-dependent enzymes. Additional NYSGXRC efforts were required to obtain the structure of the enzyme with Mg2+ ion bound (PDB ID: 2GGE). We believe that such special efforts are both justified and essential for prosecution of community-solicited targets. It does not advance the science of the community nominator should the resulting structure fail to provide the desired information (in this case, proper metal placement and coordination to support computational ligand identification).

Gerlt (PPG) and Raushel (PPG) are currently using small-molecule compound library screening methods to provide direct functional annotations with NYSGXRC-provided protein samples.

To date, Gerlt has identified biochemical function for seven ENs, including four O-succinylbenzoate synthases, two L-rhamnonate dehydratases, and a D-galacturonatedehydratase. Structural analyses themselves can also provide information regarding putative function. For example, the structure of the unliganded form of target 9265a demonstrated well-ordered ’’20s and 50s’’ loops, which are typically disordered in the absence of bound ligand. These features result in an active site that appears to be considerably ’’more open’’ than most unliganded ENs, suggesting that the natural ligand/substrate might be polymeric. This hypothesis is currently being tested by Gerlt and coworkers.

TABLE 40.3 NYSGXRC Structures of Community-Nominated Enolases and Amidohydrolases

To date, Raushel has screened small-molecule compound libraries appropriate for the AHs and produced five tentative biochemical annotations for three putative dipeptidases and two putative N-acyl-D-amino acid deacetylases (DAAs). These studies are now being complemented by direct metal analysis. NYSGXRC efforts on the AHs also enabled a remarkable example of structure-guided functional annotation. The structure of Tm0936, a putative member of the AH family, was determined during PSI-I (by both NYSGXRC and JCSG). Shoichet (PPG), Raushel (PPG), Almo (NYSGXRC and PPG) and coworkers performed extensive computational docking to successfully identify substrates of the enzyme (Hermann et al., 2007). A unique feature of this computational effort was the use of high-energy conformations that mimic reaction intermediates; such high-energy intermediates may be better suited to capturing substrate-protein interactions than are ground states. Shoichet’s docking hit list was dominated by 6-amino-purine analogues. Raushel then demonstrated that three of these compounds, including 5-methylthioadenosine and S-adenosylhomocysteine, exhibited substantial turnover in the presence of the enzyme (105/Ms). Definitive confirmation of this related group of substrates followed with Almo’s X-ray crystal structure determination of Tm0936 bound to the product of S-adenosylho-mocysteine deamination, S-inosylhomocysteine (PDB ID: 2PLM). The experimental structure is remarkably similar to that predicted by Shoichet with computational docking. Further work documented that these deamination products are further metabolized by Thermotoga maritima via a previously uncharacterized S-adenosylhomocysteine degradation pathway. Our collaborative efforts with the Gerlt/Raushel PPG clearly demonstrate the power and potential of structure-guided computational approaches for ligand/substrate discovery and functional annotation, provided both protein reagents and X-ray structures are readily available.

COMMUNITY-NOMINATED TARGETS: CONCLUSION

The NYSGXRC community-nominated target structure determination program is proving highly effective as (1) it is servicing a large programmatic effort addressing functional assignment, a major issue in the postgenomic era; (2) it leverages the expertise/platform of the NYSGXRC; (3) it maximizes the value of each purified protein, as, in addition to our crystallographic efforts, these materials support a wide range of mechanistic solution-based studies, and (4) it has already provided novel structural information that can be translated into function/mechanistic insight.

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS

Structural genomics studies of protein superfamilies by the NYSGXRC during the first two years of the second phase of the NIH-funded Protein Structure Initiative have already yielded a considerable wealth of new experimental X-ray crystal structures. In addition, our efforts have produced reagents (i.e., expression clones, protocols for E. coli fermentation and protein purification and crystallization, and purified proteins) that are proving valuable to researchers seeking to understand protein structure/function relationships. During the remainder of PSI-II, the NYSGXRC plans to continue its biomedical theme studies of the protein phosphatase family and its community-nominated collaborative studies of the enolase and amidohydrolase superfamily with Gerlt/Raushel and coworkers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NYSGXRC is supported by NIH Grant U54 GM074945 (principal investigator: S.K. Burley). We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all members of the NYSGXRC, past and present.